Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(3):168-175

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Clostridioides difficile infection have recently been updated. Risk factors include recent exposure to health care facilities or antibiotics, especially clindamycin. C. difficile infection is characterized by a wide range of symptoms, from mild or moderate diarrhea to severe disease with pseudomembranous colitis, colonic ileus, toxic megacolon, sepsis, or death. C. difficile infection should be considered in patients who are not taking laxatives and have three or more episodes of unexplained, unformed stools in 24 hours. Testing in these patients should start with enzyme immunoassays for glutamate dehydrogenase and toxins A and B or nucleic acid amplification testing. In children older than 12 months, testing is recommended only for those with prolonged diarrhea and risk factors. Treatment depends on whether the episode is an initial vs. recurrent infection and on the severity of the infection based on white blood cell count, serum creatinine level, and other clinical signs and symptoms. For an initial episode of nonsevere C. difficile infection, oral vancomycin or oral fidaxomicin is recommended. Metronidazole is no longer recommended as first-line therapy for adults. Fecal microbiota transplantation is a reasonable treatment option with high cure rates in patients who have had multiple recurrent episodes and have received appropriate antibiotic therapy for at least three of the episodes. Good antibiotic stewardship is a key strategy to decrease rates of C. difficile infection. In routine or endemic settings, hands should be cleaned with either soap and water or an alcohol-based product, but during outbreaks soap and water is superior. The Infectious Diseases Society of America does not recommend the use of probiotics for prevention of C. difficile infection.

Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) is an anaerobic, spore-forming, gram-positive bacillus identified in 1978 as the primary cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis.1 The rate of C. difficile infections increased from 13 to 14.2 cases per 1,000 adults between 2011 and 2015; it is now the most commonly reported nosocomial pathogen in the United States.2 Health care costs associated with C. difficile infection were estimated at $4.8 billion for acute care facilities in 2008.3 This article discusses recently updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of C. difficile infection.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Avoid testing for a Clostridioides difficile infection in the absence of diarrhea. | Infectious Diseases Society of America |

| Do not use antibiotics in patients with recent C. difficile infection without convincing evidence of need. Antibiotics pose a high risk of C. difficile recurrence. | Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America |

Risk Factors

Antibiotic use is the most widely recognized risk factor for C. difficile infection, and longer courses further increase the risk. Any antimicrobial agent can cause C. difficile infection, but clindamycin is the most common (Table 1).4,5 Other risk factors include severe illness, being older than 70 years, gastric acid suppression, enteral feeding, gastrointestinal surgery, small bowel obstruction, obesity, hematopoietic stem cell and solid organ transplantation, inflammatory bowel disease, cirrhosis, being peripartum, chronic kidney disease, hyperglycemia, hypoalbuminemia, and leukocytosis 6,7 (Table 27).

| Antibiotic | Odds ratio (95% CI)* |

|---|---|

| Clindamycin | 16.80 (7.48 to 37.76) |

| Cephalosporins, monobactams, and carbapenems | 5.68 (2.12 to 15.23) |

| Fluoroquinolones | 5.50 (4.26 to 7.11) |

| Penicillin | 2.71 (1.75 to 4.21) |

| Macrolides | 2.65 (1.92 to 3.64) |

| Sulfonamides and trimethoprim | 1.81 (1.34 to 2.43) |

| Tetracyclines | 0.92 (0.61 to 1.4) |

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Abnormal findings on abdominal computed tomography | 13.5 (5.72 to 32.07) |

| Minimum albumin level < 2.5 g per dL (25 g per L) | 3.44 (1.56 to 7.57) |

| Age > 70 years | 3.35 (1.48 to 7.57) |

| Small bowel obstruction or ileus | 3.06 (1.0 to 9.39) |

| Maximum leukocyte count > 20,000 per μL (20.0 × 109 per L) | 2.77 (1.28 to 6.0) |

| Maximum creatinine level > 2 mg per dL (153 μmol per L) | 2.4 (1.04 to 5.88) |

| Recent hospitalization (within 30 days) | 1.39 (0.61 to 3.18) |

| Skilled nursing facility/rehabilitation stay | 1.11 (0.46 to 2.68) |

A recent retrospective cohort study of adults with C. difficile infection in the Veterans Health Administration found that 60% of cases were diagnosed after more than two days of hospitalization; these were classified as health care facility–acquired infections.8 The remaining 40% were community-acquired infections, and on average 62% of these were associated with antibiotic use. Over the 11-year study, the proportion of community-acquired cases not associated with antibiotic use increased steadily, eventually exceeding the number of cases associated with antibiotic use. During the same period, health care facility–acquired infections decreased from 74% to 53% of cases.

Asymptomatic colonization is common in children, especially infants.6 Up to 63% of healthy neonates are colonized with C. difficile, and evidence suggests that hospitalization during birth is a factor.10 Most infants are colonized with nontoxogenic strains that may stimulate a protective immune response.2,6 Infants who are colonized with toxic strains may transmit the bacteria to adults.2 Risk factors for C. difficile infection in children are similar to those for adults.6

Transmission

Transmission of C. difficile most likely occurs by person-to-person contact via the fecal-oral route or by direct exposure from the contaminated environment. In 134 hospitalized patients who acquired C. difficile infection, occupying a room where a prior occupant had the infection significantly increased the risk (hazard ratio = 2.35).11 Electronic rectal thermometers and inadequately cleaned commodes and bedpans are particularly high-risk fomites.6 Shedding of C. difficile spores may continue after treatment is complete and diarrhea has resolved, resulting in asymptomatic carriers.

Microbiology and Pathophysiology

The incubation period for C. difficile is up to one week, although recent studies suggest it could be longer.6 C. difficile survives outside the colon as spores that are resistant to heat, acid, and antibiotics. Once spores are in the colon, they germinate to their fully functional vegetative, toxin-producing forms and become susceptible to antibiotics. C. difficile colonizes the large intestine and releases two potent exotoxins that mediate colitis and diarrhea. Toxins A (enterotoxin) and B (cytotoxin) cause inflammation leading to mucosal injury and intestinal fluid secretion. Toxigenic C. difficile produces both toxins or only toxin B, which is essential to the cytotoxicity of C. difficile.12,13

Recurrence

Recurrent C. difficile infection is defined by resolution of symptoms during therapy, then reappearance of symptoms two to eight weeks after treatment has ended. The recurrence rate for health care facility–acquired infections is 5% to 50% (median: 20%).3 A meta-analysis found that 13% to 50% of patients with C. difficile infection had at least one recurrence.14 A subset of patients will have multiple recurrences after at least three 14-day courses of appropriate antibiotics. From 2001 to 2012, the incidence of such cases increased 188.8%.15 Recurrences are likely due to treatment failure rather than reinfection with a different strain of C. difficile.16

Clinical Manifestations

C. difficile infection is characterized by a wide range of symptoms, from mild or moderate diarrhea—often mucoid stool with minimal blood—to severe disease with pseudo-membranous colitis, colonic ileus, toxic megacolon, sepsis, or death. Other possible symptoms include fever, abdominal pain or cramping, decreased appetite, and malaise.17 Small studies have found that stool odor was neither sensitive nor specific for C. difficile infection.18

Diagnostic Testing

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America recommend limiting testing for C. difficile infection to patients with unexplained onset of three or more unformed stools in 24 hours while not taking laxatives.6 The 2017 IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis and management of infectious diarrhea recommend testing in patients older than two years after antibiotic use, and in those with health care–associated diarrhea or persistent diarrhea in the absence of risk factors or a known cause.19

Because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic C. difficile colonization in infants, the IDSA does not recommend testing for C. difficile in children 12 months or younger who have diarrhea.6,20 Testing is recommended only for children older than 12 months who have prolonged diarrhea and risk factors (e.g., malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, Hirschsprung disease, immunocompromising conditions, structural intestinal disorders), and only after other causes of diarrhea have been ruled out.6

When the prevalence of C. difficile infection is low, no diagnostic test should be used alone because of low positive predictive values. The reference tests with which other assays are compared include cell cytotoxicity neutralization assay and toxigenic culture, both of which have relatively long turnaround times and are thus rarely used in clinical practice. Other diagnostic tests include enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for toxins A and B and for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), an enzyme made by all C. difficile strains (Table 3).21 Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) detects genes that encode the toxins, but it cannot distinguish colonization from active infection. The EIA for GDH has high sensitivity, which makes it a useful screening test because a negative result essentially rules out infection (negative predictive value = 94% to 100%). The EIA for toxins A and B has the highest specificity, whereas NAAT is both sensitive and specific. The choice of diagnostic test depends on local preference, financial constraints, and volume of samples tested each day.6,21,22

| Compared with cytotoxicity neutralization assayCompared with toxigenic culture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| Enzyme immunoassay for glutamate dehydrogenase | 94% (89 to 97) | 90% (88 to 92) | 96% (86 to 99) | 96% (91 to 98) |

| Enzyme immunoassay for toxins A and B | 83% (76 to 88) | 99% (98 to 99) | 57% (51 to 63) | 99% (98 to 99) |

| Nucleic acid amplification test | 96% (93 to 98) | 94% (93 to 95) | 95% (92 to 97) | 98% (97 to 99) |

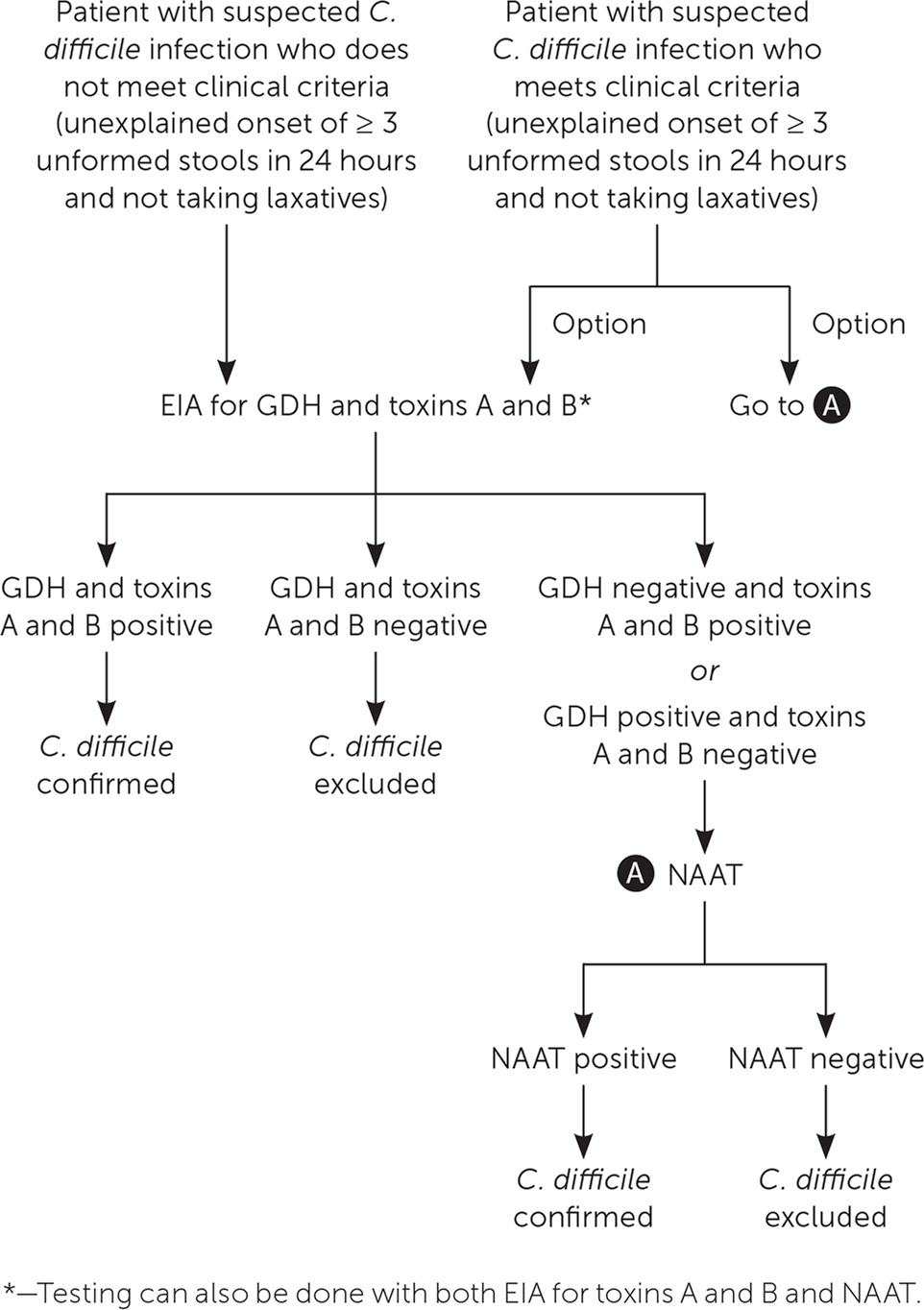

In facilities that limit C. difficile testing to patients with three or more unformed stools per 24 hours, testing can begin with NAAT or EIAs for GDH and toxins A and B (Figure 1). If the facility does not limit C. difficile testing and evaluates patients who do not meet testing criteria, EIAs for GDH and toxins A and B can be performed initially; if results are inconclusive, NAAT alone or in combination with an EIA for toxins A and B can be ordered. NAAT alone should not be performed in patients with a lower probability of C. difficile infection because a positive test could reflect asymptomatic colonization.6,21

ADJUVANT TESTING

The presence of peripheral leukocytosis, lactic acidosis, or hypoalbuminemia indicates more severe C. difficile infection. Adjuvant tests such as fecal hemoccult and lactoferrin are not recommended for assessment of disease severity.6 In patients with signs of severe disease, radiographic imaging (e.g., plain radiography, contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis) can be considered to look for colonic dilation, colonic wall thickening, pericolonic stranding, and ascites. Toxic megacolon with distention and pneumoperitoneum with perforation may occur in patients with severe infection.23

REPEAT TESTING

Repeat testing within seven days during the same episode of diarrhea is not recommended because the high sensitivity of the tests can lead to false-positive results.6 Testing for cure is not recommended in patients with a previous positive test because more than 60% of patients remain C. difficile positive even after treatment.24

Treatment for Adults

The first step in identifying the correct treatment strategy is to determine the severity of the infection. Based on expert opinion, the proposed criteria for C. difficile infection severity are:6

Nonsevere infection: white blood cell count of 15,000 per mL (15.0 × 109 per L) or less and serum creatinine level less than 1.5 mg per dL (133 mmol per L)

Severe infection: white blood cell count greater than 15,000 per mL or serum creatinine level of 1.5 mg per dL or greater

Fulminant colitis: hy potension, shock, ileus, or megacolon

Nonsevere C. difficile infection is further stratified by initial episode and number of recurrent infections, and the treatment strategy depends on how many episodes the patient has experienced. It is reasonable to start antibiotics empirically if diagnostic test results will take longer than 48 hours to obtain or if the patient presents with fulminant colitis.6 Patients who are clinically stable can be treated on an outpatient basis after they have been counseled about infection control.

INITIAL EPISODE

The 2017 IDSA guidelines recommend oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin (Dificid) for treatment of nonsevere initial C. difficile infection (Table 4).6 Multiple randomized, placebo-controlled trials have shown that oral vancomycin is superior to metronidazole, which is no longer recommended as a first-line treatment for initial episodes of C. difficile infection.6 Fidaxomicin is associated with a lower recurrence rate than oral vancomycin, but it is more expensive.6 If oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin is unavailable, oral metronidazole can be used. However, C. difficile is becoming increasingly resistant to metronidazole.25

| Episode | Treatment regimen | Strength of recommendation/quality of evidence* |

|---|---|---|

| Initial infection | Nonsevere | |

| Vancomycin, 125 mg orally 4 times per day for 10 days | Strong/high | |

| or | ||

| Fidaxomicin (Dificid), 200 mg orally 2 times per day for 10 days | Strong/high | |

| If neither agent is available: metronidazole, 500 mg orally 3 times per day for 10 days | Weak/high | |

| Severe | ||

| Vancomycin, 125 mg orally 4 times per day for 10 days | Strong/high | |

| or | ||

| Fidaxomicin, 200 mg orally 2 times per day for 10 days | Strong/high | |

| Fulminant | ||

| Vancomycin, 500 mg orally or via nasogastric tube 4 times per day plus metronidazole, 500 mg intravenously every 8 hours (particularly if ileus is present) | Strong/moderate | |

| First recurrence | Vancomycin, 125 mg orally 4 times per day for 10 days if metronidazole was used for the initial episode | Weak/low |

| or | ||

| Prolonged taper and pulsed vancomycin regimen† if standard regimen was used for the initial episode | Weak/low | |

| or | ||

| Fidaxomicin, 200 mg orally 2 times per day for 10 days if vancomycin was used for the initial episode | Weak/moderate | |

| Second or subsequent recurrence | Prolonged taper and pulsed vancomycin regimen† | Weak/low |

| or | ||

| Vancomycin, 125 mg orally 4 times per day for 10 days, followed by rifaximin (Xifaxan), 400 mg orally 3 times per day for 20 days | Weak/low | |

| or | ||

| Fidaxomicin, 200 mg orally 2 times per day for 10 days | Weak/low | |

| or | ||

| Fecal microbiota transplantation | Strong/moderate |

FIRST RECURRENCE

Approximately 25% of patients treated with vancomycin for C. difficile infection have at least one additional episode.26 Treatment options for the first recurrence include vancomycin if metronidazole was used for the initial episode, or if a standard vancomycin regimen was used for the initial episode, either fidaxomicin or a prolonged vancomycin taper followed by pulsed vancomycin (Table 4).6

SUBSEQUENT RECURRENCE

There are several treatment options for patients who have had multiple recurrent episodes of C. difficile infection and have received appropriate antibiotic therapy for at least three episodes (Table 4).6 Vancomycin can be given, either in a tapered and pulsed regimen or four times per day for 10 days followed by rifaximin (Xifaxan) three times per day for 20 days. Alternatively, fidaxomicin can be used twice per day for 10 days. Fecal microbiota transplantation is also a reasonable option.6 It involves instillation of processed stool from a healthy donor into the intestinal tract of the patient through a colonoscope, feeding tube, enema, or capsules. Multiple randomized trials have shown cure rates ranging from 70% to 90%.6 Fecal microbiota transplantation is less effective in patients with underlying inflammatory bowel disease.27 It is generally safe but has mild to moderate self-limited adverse events (e.g., abdominal discomfort).28 Rare potential complications include aspiration, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and colonic perforation.28 Long-term consequences are unknown.6

SEVERE DISEASE AND FULMINANT COLITIS

Patients with severe C. difficile infection or fulminant colitis should receive immediate antibiotic therapy, supportive care, and close monitoring in a hospital setting. Some may require surgery for toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, or necrotizing colitis.6

Antibiotics for fulminant colitis include enteral vancomycin and parenteral metronidazole.8 If there is no clinical improvement within three to five days, fidaxomicin can be added. Patients who have delayed passage of oral antibiotics due to an ileus can be given intracolonic vancomycin rectally via retention enema every six hours with or without intravenous metronidazole every eight hours.29 Monitoring serum creatinine levels is important while using high doses of vancomycin, especially if the patient has underlying chronic kidney disease. Continuing treatment with the antibiotic presumed to have caused the infection prolongs diarrhea and increases the risk of treatment failure and recurrent infections,30–32 so the antibiotic should be stopped, if possible, or switched to another agent that is less likely to cause C. difficile infection.

Other strategies with less evidence for effective treatment of C. difficile infection include the use of probiotics and bezlotoxumab (Zinplava), the first human monoclonal antibody to C. difficile toxin B that was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Most guidelines recommend against the use of probiotics as adjunctive therapy because of a lack of good-quality studies that show benefit. A small study examined staggered and tapered antibiotic withdrawal in combination with probiotic kefir started after completion of a standard treatment regimen.33 The study showed cure rates similar to those with fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent C. difficile infection. In two industry-sponsored randomized controlled trials, the addition of a single intravenous dose of bezlotoxumab to the standard treatment course decreased rates of recurrent C. difficile infection.34

Treatment for Children

There are limited data and no randomized controlled trials on the optimal approach to treatment of C. difficile infection in children. Metronidazole or vancomycin is recommended for children with an initial or first recurrence of nonsevere infection; for severe initial episodes or nonsevere recurrent episodes, oral vancomycin is preferred over metronidazole based on observational studies. Fidaxomicin is not approved for use in children younger than 18 years. Fecal microbiota transplantation can be used in children with multiple recurrences in whom standard antibiotic therapy is ineffective.6

Prevention and Control

Infection control and good antibiotic stewardship are the cornerstones for reducing the incidence of C. difficile infection in health care and community settings. Infection control requires a robust surveillance system to detect increased infection rates or outbreaks of C. difficile infection; in addition, key preventive strategies include use of contact precautions, good hand hygiene, environmental cleaning and disinfection, and patient bathing. Contact precautions (e.g., private rooms with a private bathroom, putting on gloves and gowns on entry to the patient's room and removing them before exiting) should commence when C. difficile infection is suspected and should continue for at least 48 hours after resolution of the patient's diarrhea.6

In routine or endemic settings, hands should be cleaned with either soap and water or an alcohol-based product before and after contact with a patient and after removing gloves.6 During outbreaks or when direct contact with feces is likely, the use of soap and water is preferred over alcohol-based products35 based on two small studies that showed that using soap and water vs. alcohol-based products was more effective for reducing C. difficile colony-forming units.36,37 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency–registered sporicidal agents should be used to disinfect surfaces with which the patient has come into contact.6 Disposable equipment such as stethoscopes and thermometers should be used, and patients should wash their hands and shower regularly to reduce the number of spores on the skin.6 In a study of patients with C. difficile infection, showering significantly reduced positive C. difficile skin cultures vs. bed bathing.35

In community and childcare settings, patients with C. difficile infection should wash their hands with soap and water after using the bathroom, before eating or preparing food, and when hands are visibly soiled.6 Patients with diarrhea should avoid using the same toilets as other family members, and the bathroom and kitchen should be cleaned with bleach-containing solutions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidance for cleaning products and for preventing contamination of medical equipment (https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol).

Antibiotic stewardship that targets restriction of high-risk antibiotics can help control outbreaks and reduce infection rates; multiple studies have shown reductions of 33% to 90%.6 Similar to inpatient management, outpatient management relies on implementing an antibiotic stewardship program and minimizing the frequency and duration of antibiotic therapy, as well as the number of antimicrobial agents used. Hand washing and barrier precautions should also be used in the outpatient setting.

The use of probiotics for the prevention of C. difficile infection and, more specifically, C. difficile–associated diarrhea has also been examined. A 2017 Cochrane review of 39 studies found moderate evidence that probiotics are effective for preventing C. difficile–associated diarrhea, but only in trials where the C. difficile event rate was more than 5%.38 In these studies, probiotics had a number needed to treat of 12 to prevent C. difficile–associated diarrhea. Investigators determined that 27 of the studies were at high or unclear risk of bias, and there was marked heterogeneity between the studies in probiotic formulations, duration of administration, definitions of C. difficile infection, and duration of follow-up.6 Probiotics may impede recovery of normal gut flora after antibiotic use39 and increase the risk of bacteremia and fungemia in immunocompromised people.40 Because of the potential bias and variations in the Cochrane review and the potential for harm from probiotic use, the IDSA concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend probiotics as a preventive measure.6 There is also insufficient evidence to recommend stopping proton pump inhibitors and histamine H2 blockers to decrease the incidence of C. difficile infection.6

There is insufficient evidence to recommend screening for asymptomatic carriers of C. difficile, or for instituting contact precautions for asymptomatic carriers.6 Thus, it is not necessary to screen or treat close contacts if they are asymptomatic.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Winslow, et al.,41 and by Schroeder.42

Data Sources: A PubMed search limited from 2013 through 2018 was completed using the following keywords and subject headings: Clostridium difficile, Clostridioides, cdiff, c diff, C difficile, or Clostridium difficile [MeSH]. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, controlled trials, and reviews. A keyword search was also performed in UpToDate for additional articles on this topic. Search dates: June 2018 to August 2019.