Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(5):307-308

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

A 68-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from long-term tobacco use presented to the emergency department with worsening shortness of breath over the previous week. Simple tasks such as walking to the mailbox or up a flight of stairs exacerbated his dyspnea. His chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was managed with albuterol and tiotropium (Spiriva) inhalers, and he had never been hospitalized for an exacerbation.

His medical history was significant for longstanding hypertension and hyperlipidemia and a recent diagnosis of a nonobstructing lung cancer. His additional medications included amlodipine (Norvasc) and atorvastatin (Lipitor). The patient was retired, drank one or two alcoholic beverages daily, and had a 60-pack-year smoking history. He did not use illicit drugs.

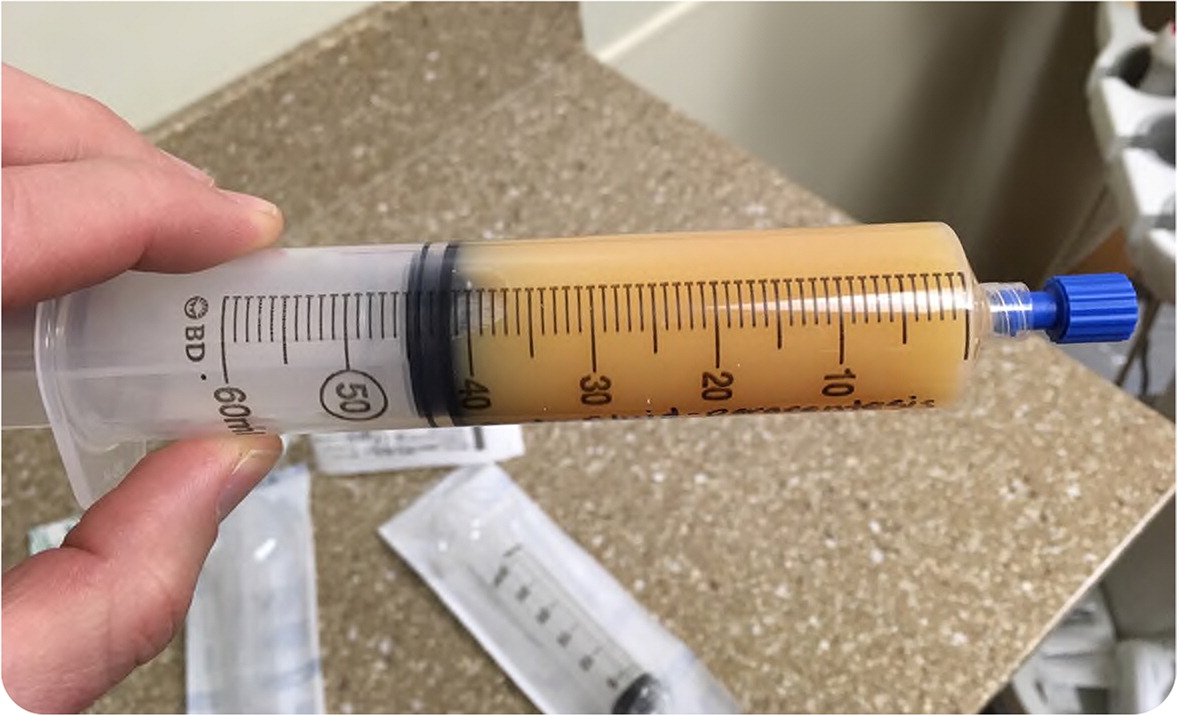

His vital signs were significant for blood pressure of 155/75 mm Hg, pulse of 95 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute. His oxygen saturation level was 85% on room air but improved to 94% on 2 L of oxygen. Physical examination revealed diminished breath sounds and dullness to percussion at the right base but was otherwise normal. Chest radiography confirmed a large right-sided pleural effusion. Pleural fluid was opaque on thoracentesis (Figure 1).

Question

Discussion

The answer is A: chylothorax. Chylothorax develops when the thoracic duct is damaged, causing large amounts of chyle containing triglycerides/chylomicrons, T lymphocytes, electrolytes, proteins, and fat-soluble vitamins to flow into the pleural space. Chylothorax appears as milky or cloudy pleural fluid.1,2 When evaluating pleural fluid, Light criteria can be used to distinguish between an exudate and a transudate. Fluid is exudative if pleural fluid protein divided by serum protein is greater than 0.5; pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) divided by serum LDH is greater than 0.6; or pleural fluid LDH is more than two-thirds the upper limit of normal for serum LDH.3

Malignancy, such as lymphoma, is the leading cause of chylothorax.4,5 Surgical injuries, nonmalignant masses, and trauma are other important causes. In up to one-half of chylothorax cases, the fluid is not grossly milky, but fluid analysis demonstrates high levels of triglycerides and cholesterol. Although this patient had lung cancer, malignancy is more often associated with bloody red or brown effusion.

Conditions such as congestive heart failure, liver failure, and nephropathies may cause a transudative effusion as a result of disruptions in oncotic or hydrostatic pressure in the pleural space. It is pale or straw-colored and typically not milky.6

Parapneumonic effusion can be straw-colored or purulent.7 Patients have evidence of pneumonia, such as cough, fever, or other infectious symptoms. Frank pus may be present in the case of an empyema; however, the effusion is rarely milky or cloudy. Parapneumonic effusion can be sterile (uncomplicated) or infected (complicated).

Pseudochylothorax is the presence of cholesterol-rich fluid associated with chronic inflammatory disorders, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis or tuberculosis.8 Although the fluid often appears milky or cloudy, patients will have symptoms of inflammatory disease. Additionally, a pseudochylothorax typically has a more gradual onset than chylothorax, developing over several months to years.

| Type of effusion | Causes | Characteristics of effusion |

|---|---|---|

| Chylothorax | Thoracic duct damage causes large amounts of chyle containing triglycerides/chylomicrons, T lymphocytes, electrolytes, proteins, and fat-soluble vitamins to flow into the pleural space | Milky or cloudy; in up to one-half of cases, the fluid is not grossly milky but contains high levels of triglycerides and cholesterol |

| Transudative effusion | Disruptions in oncotic or hydrostatic pressure in the pleural space such as with heart failure, liver failure, and nephropathies | Pale or straw-colored |

| Parapneumonic effusion | Pleural effusions develop in the setting of pneumonia; can be sterile (uncomplicated) or infected (complicated) | Straw-colored or purulent; frank pus may be present in the case of an empyema |

| Pseudochylothorax | Cholesterol-rich fluid associated with chronic inflammatory disorders, most commonly rheumatoid arthritis or tuberculosis | Milky or cloudy |