Editor's Note: This article has been updated to incorporate the January 2021 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(1):22-32

Related letter: The Role of Weight Stigma in the Development of Eating Disorders

Patient information: See related handout on eating disorders.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Eating disorders are potentially life-threatening conditions characterized by disordered eating and weight-control behaviors that impair physical health and psychosocial functioning. Early intervention may decrease the risk of long-term pathology and disability. Clinicians should interpret disordered eating and body image concerns and carefully monitor patients' height, weight, and body mass index trends for subtle changes. After diagnosis, visits should include the sensitive review of psychosocial and clinical factors, physical examination, orthostatic vital signs, and testing (e.g., a metabolic panel with magnesium and phosphate levels, electrocardiography) when indicated. Additional care team members (i.e., dietitian, therapist, and caregivers) should provide a unified, evidence-based therapeutic approach. The escalation of care should be based on health status (e.g., acute food refusal, uncontrollable binge eating or purging, co-occurring conditions, suicidality, test abnormalities), weight patterns, outpatient options, and social support. A healthy weight range is determined by the degree of malnutrition and pre-illness trajectories. Weight gain of 2.2 to 4.4 lb per week stabilizes cardiovascular health. Treatment options may include cognitive behavior interventions that address body image and dietary and physical activity behaviors; family-based therapy, which is a first-line treatment for youths; and pharmacotherapy, which may treat co-occurring conditions, but should not be pursued alone. Evidence supports select antidepressants or topiramate for bulimia nervosa and lisdexamfetamine for binge-eating disorder. Remission is suggested by healthy biopsychosocial functioning, cognitive flexibility with eating, resolution of disordered behaviors and decision-making, and if applicable, restoration of weight and menses. Prevention should emphasize a positive focus on body image instead of a focus on weight or dieting. .

Eating disorders are potentially life-threatening conditions characterized by disordered eating and weight-control behaviors that impair physical health and psychosocial functioning.1–3 Adolescence and early adulthood are vulnerable periods for the development of eating disorders; however, up to 8% of females and 2% of males are affected during their lifetimes, including persons of all ages, sizes, sexual and gender minority groups, races, ethnicities, socioeconomic strata, and geographic locations.1,4–6 Diagnostic characteristics of specific eating disorders are presented in Table 1.2

| Anorexia nervosa |

| Restriction of food eaten, leading to significantly low body weight |

| Intense fear of gaining weight or being “fat” |

| Body image distortion |

| Types: restrictive or binge eating/purging |

| Alternative diagnosis: atypical anorexia nervosa (i.e., weight is not significantly low)* |

| Bulimia nervosa |

| Binge eating (i.e., eating more food than peers [e.g., over a two-hour period] accompanied by a perceived loss of control) |

| Repeated use of unhealthy behaviors to prevent weight gain, such as vomiting, misuse of laxatives or diuretics, food restriction, or excessive exercise |

| Self-worth is overly based on body shape and weight |

| Behaviors occur at least weekly for at least three months and are distinctly separate from anorexia nervosa |

| Alternative diagnoses: bulimia nervosa of low frequency and/or limited duration*; purging disorder (i.e., recurrent purging to lose weight without binge eating)* |

| Binge-eating disorder |

| Recurrent episodes of binge eating (i.e., eating more food than peers [e.g., over a two-hour period] accompanied by a perceived loss of control) |

| Associated with three of the following: eating faster than normal, eating until feeling uncomfortable, eating large quantities of food when not hungry, feeling bad because of embarrassment about eating behaviors, or eating followed by negative emotions |

| No behaviors to prevent weight gain |

| Behaviors occur at least weekly for at least three months and are distinctly separate from anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa |

| Alternative diagnosis: binge-eating disorder of low frequency and/or limited duration* |

| Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder |

| Avoidance of food intake because of one of the following: lack of interest, sensory characteristics of food, concern about consequences of eating that lead to unmet nutritional or energy needs |

| Associated with significant weight loss, inadequate weight gain during growth, nutritional deficiency, interference with psychosocial functioning, or dependence on supplemental feeding |

| Not explained by food availability, culturally sanctioned practice, or other medical or mental health condition |

| No disturbance in how body weight or shape is experienced by the person |

| Rumination disorder |

| Repeated regurgitation of food for at least one month |

| Not attributable to a gastrointestinal or other medical condition |

| Does not occur exclusively with another eating disorder |

| Pica |

| Eating nonnutritive, nonfood substances for at least one month |

| Eating behavior is developmentally inappropriate |

| Not part of a culturally supported or socially normative practice |

Persons with anorexia or bulimia nervosa have a two- to sixfold increase in age-adjusted mortality attributed to medical complications and have suicide completion rates up to 18 times the completion rates of peers.7–10 At least one-third of persons with disordered eating develop persistent symptoms that remain 20 years postdiagnosis.11,12 Co-occurring mood, anxiety, substance use, personality, or somatic disorders are identified in more than two-thirds of persons with eating disorders.1,13 Early intervention with symptom improvement decreases the risk of a protracted course and long-term pathology.1,3,14,15

Early Identification

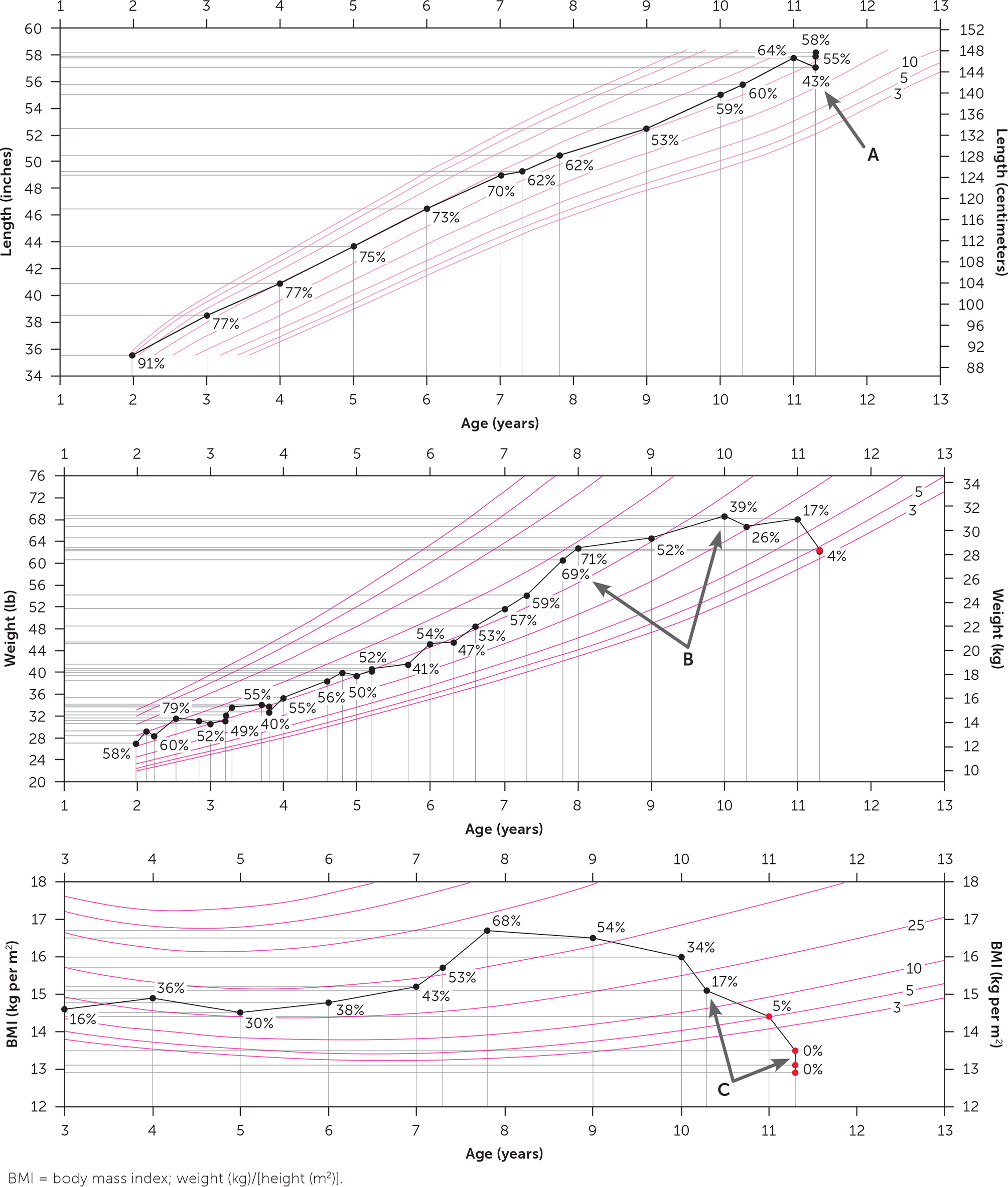

Clinicians, especially those caring for adolescents and young adults, should routinely conduct confidential psychosocial assessments that include questions about eating behaviors, body image, and mood.5,16–18,60 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is planning to review the health outcomes of screening for eating disorders and the performance of primary care–relevant screening tools.19 Clinicians should monitor patients' height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) trends, including percentile changes and growth curves for youth to avoid missing critical windows for intervention before pathology becomes entrenched20,21,60 (eFigure A). Subtle changes in the amount and speed of weight loss can be as harmful as low weight.20–22

Persons with restrictive eating disorders may perceive benefits from the disorder, minimize pathology, and resist treatment.17,20,23 Clinicians should acknowledge that a person's motivation to change may be compromised by malnutrition or co-occurring conditions, lack of self-awareness, or fear.23–25 Disordered thoughts and behaviors may provide perceived structure, self-worth, and safety in coping with difficult emotions and stressors.23–25 Initial praise of the patient's weight loss by family members, peers, or clinicians may lead to fear of regaining weight and body image distortion.5 In males, body dissatisfaction may center on muscularity and leanness, leading to rigid routines and use of appearance- or performance-enhancing substances.26 “Bulk and cut” routines, which involve cycles of excessive energy intake for muscle building followed by caloric deficit to achieve visible muscularity, may mimic binge-purge pathology.27

The use of empathetic, nonjudgmental motivational inter viewing techniques (e.g., “I'm curious about your meal preparation routine. Is it stressful for you?” or “Given your experiences, your skepticism is appreciated.”) may help overcome barriers and patient resistance16,17,25,28 (Table 224,29). The patient's history should be corroborated by family members and other contacts, ideally. Clinicians should note objective findings and interpret screening tools such as the SCOFF questionnaire in context because critical information may be withheld17,20,23,30 (eTable A).

| Goal | Questions or statements |

|---|---|

| Start a conversation about eating habits | I'm concerned about your eating. May we discuss how you typically eat? |

| Would it be okay if we discussed your eating habits? | |

| Assess motivation to change eating habits | How would your life be different if you didn't need to spend so much time thinking about your eating? |

| It sounds like your eating habits are really important for helping you get through the day. | |

| On a scale of 0 to 10, how confident are you that you could change the way you eat? | |

| On a scale of 0 to 10, how important is it for you to change your eating? What would make it more important? | |

| What do you like about the way you eat? What do you dislike? | |

| What would be the benefits of changing the way you eat? | |

| What would be the downside of changing the way you eat? | |

| What would make you more confident? | |

| Determine the antecedents and consequences of disordered eating patterns | Do you ever feel that you lose control over the way you eat? How often does that happen? |

| How does eating impact your ability to function during the day? Do you feel tired? | |

| How do you feel before you binge? After you binge? Before you purge? After you purge? | |

| Is it difficult to concentrate? | |

| Some of my patients tell me that their weight or body shape causes stress. Tell me about any experiences or struggles you have had. | |

| Sometimes people binge and purge when they are overwhelmed, stressed, sad, or anxious; do any of those situations apply to you? | |

| Sometimes people think about how they are eating all day to the point that it is difficult to concentrate on anything else. Does that happen to you? | |

| What happens after you purge? | |

| What would your ideal weight be? What is your healthy weight? (To assess thought patterns, not to determine goal weight.) | |

| When are you most likely to binge? | |

| Develop coping strategies | When you feel an urge to binge, what could you do instead of bingeing? Consider activities that you could do in situations when you are most likely to binge (or restrict food). |

| Change negative thinking | What can you control? |

| Who demands that you must be perfect? | |

| Who determines how you think about yourself? |

| Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full? |

| Do you worry you have lost Control over how much you eat? |

| Have you recently lost more than One stone (14 lb [6 kg]) in a three-month period? |

| Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin? |

| Would you say that Food dominates your life? |

Clinical Approach

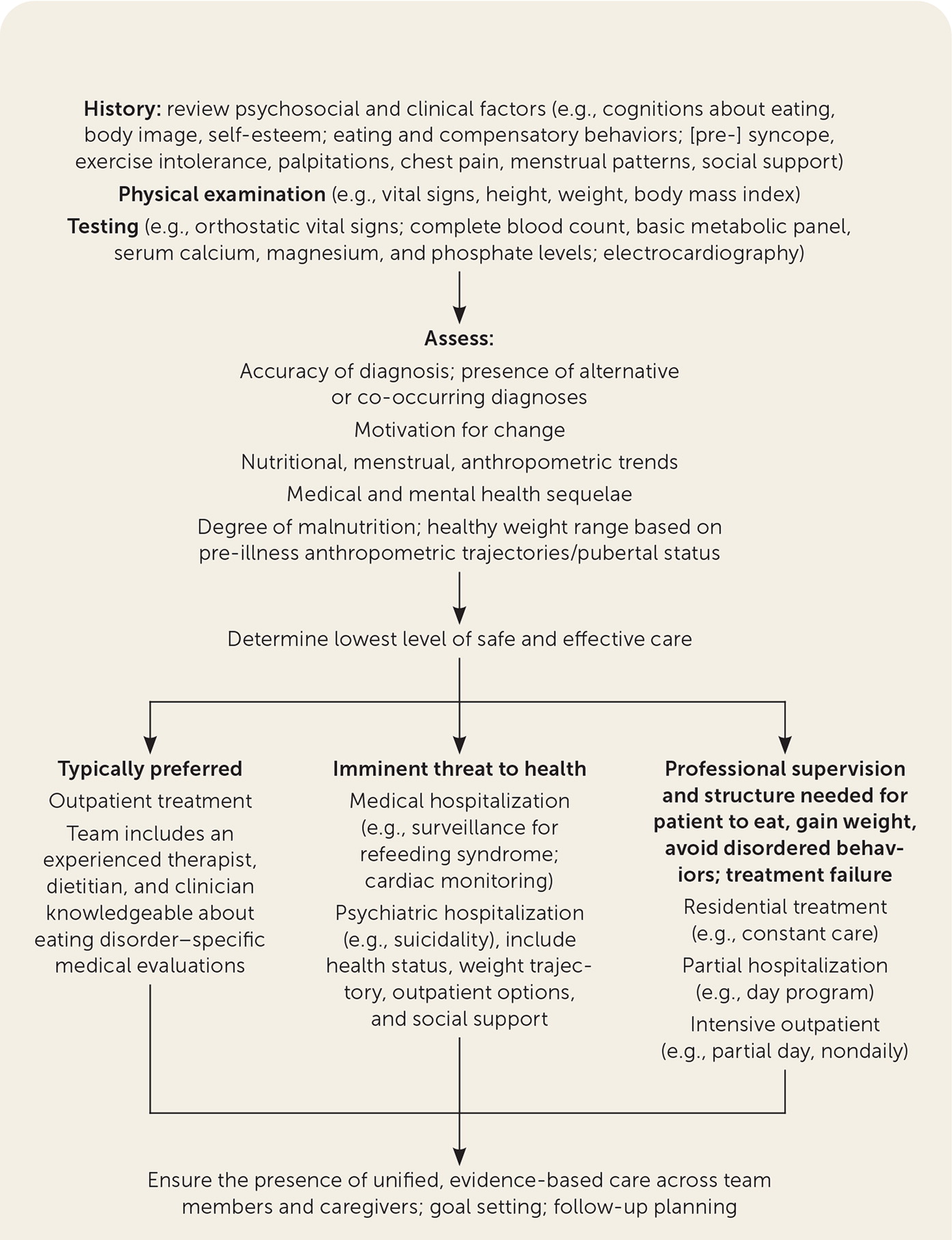

The initial medical evaluation should establish the diagnosis while excluding alternative or co-occurring diagnoses (e.g., thyroid or gastrointestinal disease) based on clarity of the clinical picture. At all related medical visits, pertinent psychosocial and clinical factors should be reviewed. A physical examination, monitoring of orthostatic vital signs, laboratory testing (e.g., a metabolic panel with magnesium and phosphate levels), and electrocardiography should also be considered (Table 3 and Table 4).1,20,25,31 Goals should include the identification of trends in nutrition, menstruation, height, weight, and BMI; the establishment of motivation for change; determination of medical and mental health sequelae; and the provision of unified, evidence-based care by team members and caregivers.3,60 Therapeutic relationships between the patient, treatment team, and caregivers should be based on rapport and trust.17,25

| Component | Findings of concern and associations |

|---|---|

| Eating- and weight-related questions | |

| Weight history | Fluctuations or extremes |

| Eating behaviors | Calorie counting, irregular or decreased food intake, picky eating, nuanced patterns or rules |

| Binge or loss-of-control eating | Presence |

| Purging behavior | Self-induced vomiting; use of diet pills, laxatives, diuretics, caffeine |

| Exercise patterns | Excessive or compulsive |

| Fear of gaining weight | Pervasive |

| Weighing, body checking | Frequent weighing, measuring, mirror use |

| Body image | Dissatisfaction; preoccupation with weight and shape; use of anabolic steroids or supplements |

| Self-esteem | Influenced by weight, shape, control of eating |

| Co-occurring mental health conditions | |

| Depression, anxiety | Presence, current and prior treatment |

| Suicidality | Ideation, plan, intent, prior suicide attempt |

| Substance use | Stimulants, alcohol, prescription medication misuse, other |

| Self-injury | Cutting, burning, self-punishing |

| Other | History of trauma, obsessive or rigid thinking, impulsivity |

| Family and social factors | |

| Social support | Inability to involve family or friends in treatment plan; possible source of stress |

| Family history | Eating disorders; missed primary or co-occurring diagnosis |

| Physical symptoms | |

| Menstrual patterns | Amenorrhea (hypothalamic dysfunction, low estrogen state) |

| Targeted questions to differential diagnoses | Malignancy; diabetes mellitus; thyroid, celiac, inflammatory bowel disease; other |

| Cardiac symptoms | Dizziness, (pre-) syncope, exercise intolerance, palpitations, chest pain (may suggest cardiac injury, malnutrition, or orthostasis) |

| Abdominal symptoms | Constipation, delayed gastric emptying, decreased intestinal mobility, pancreatitis |

| Physical examination | |

| Appearance | Flat affect, guarded |

| Body mass index, including trends and percentiles* | Down-trending or low; rapid weight loss |

| Weight, including trends and percentiles* | Down-trending or low; rapid weight loss |

| Height, including trends and percentiles* | Growth stunting |

| Blood pressure | Hypotension (e.g., malnutrition, dehydration) |

| Heart rate | Bradycardia (e.g., heart muscle wasting, metabolic changes) |

| Temperature | Hypothermia (e.g., thermoregulatory dysfunction) |

| Hair | Hair loss at scalp, lanugo |

| Mouth | Erosion of dental enamel, poor dentition (e.g., in purging) |

| Salivary glands | Hypertrophy of parotid (e.g., purging) |

| Skin and extremities | Self-harm; muscle wasting, edema (e.g., hypoalbuminemia or refeeding), dryness |

| Sexual maturity rating (adolescents) | Delayed puberty |

| Component | Findings of concern and associations |

|---|---|

| Laboratory testing* | |

| Amylase | Increased (may suggest purging) |

| Basic metabolic panel | Decreased sodium (water-loading), potassium, chloride, glucose; indications of metabolic acidosis (laxatives) or alkalosis (vomiting); acute renal injury |

| Calcium | Decreased |

| Cholesterol | Increased |

| Complete blood count | Bone marrow hypoplasia (thrombocytopenia, anemia, leukopenia) |

| Magnesium | Decreased |

| Phosphorus | Decreased |

| Prealbumin | Decreased |

| Thyroid testing | Sick euthyroid syndrome (decreased thyroxine or triiodothyronine without overt hypothyroidism) |

| Other studies | |

| Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry† | Low bone mineral density, osteopenia, osteoporosis |

| Electrocardiography | Bradycardia, arrhythmias (heart failure, electrolyte disorders), prolongation of the corrected QT interval |

| Orthostatic vital signs | Hypotension, tachycardia (may suggest dehydration or autonomic instability) |

WEIGHT ASSESSMENT

The weigh-in process at the office may be viewed by patients as stressful and requires sensitivity. Weight measurements are ideally recorded with the patient facing away from the scale in a hospital gown. The extent to which the clinician reveals weight is individualized. Because BMI percentiles do not indicate how far extreme weights deviate from the norm among youths, clinicians should use reference data to determine the degree of malnutrition (Table 5).3 Next they should determine an appropriate healthy weight range in collaboration with treatment team members, based on pre-illness height, weight, and BMI trajectories; age at pubertal onset; and current pubertal stage (affecting expected body composition).3 Describing weight in terms of percent median BMI, Z-score, and the amount and rate of weight change is more precise and preferred over ideal, expected, or median body weight terminology.3 In adults, normative BMI data and pre-illness trends can guide clinical recommendations, acknowledging that some persons are healthiest at higher weights. Home weight measurement should generally be discouraged.

NUTRITION

Traditional percentages of daily nutritional recommendations may be misleading.5,20 Moderately active adolescent females require approximately 2,200 kcal per day (adolescent males need 2,800 kcal per day) [corrected]; athletes and persons who are hypermetabolic post-recovery at any age require more.5,20 Daily caloric averages for adults can be found at https://health.gov/our-work/food-nutrition/2015-2020-dietary-guidelines. Discussions around energy intake will differ based on patient factors and choice of treatment. Some clinicians frame nutrition in terms of portions, snacks, and meals, and avoid recommending calorie counts, which may entrench disordered thinking. The multidisciplinary team should guide portion size modifications or reintroduction of foods that cause distress with caregiver endorsement. Weight gain of 2.2 to 4.4 lb (1 to 2 kg) per week stabilizes cardiovascular health.3,32

Treatment Options

ESTABLISHING A TREATMENT PLAN

Most patients receive optimal care in the outpatient setting.3,33,34 The ideal outpatient treatment team should include an experienced therapist, dietitian, and a clinician who is knowledgeable about eating disorder–specific medical evaluations, potentially in a community-based specialized center.3,33,60 Medical hospitalization (e.g., surveillance for refeeding syndrome) or psychiatric hospitalization (e.g., suicidality) may be necessary depending on health status, weight trajectory, outpatient options, and social support factors3,20,35 (Table 63).

| Acute food refusal Acute medical complications of malnutrition or purging (e.g., syncope, seizure, heart failure, pancreatitis, hematemesis) Arrested growth and development Co-occurring behavior or medical conditions that limit outpatient management (e.g., severe depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, type 1 diabetes mellitus, suicidality) Dehydration Electrocardiogram abnormalities (e.g., prolonged corrected QT interval) Electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hypokalemia, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia) Failure of outpatient treatment† | Median body mass index ≤ 75% for age and sex Physiologic instability, including autonomic dysfunction Bradycardia‡ (< 50 beats per minute during day; < 45 beats per minute at night) Hypotension (< 90/45 mm Hg) Hypothermia (< 96°F [35.6°C]) Orthostatic increase in pulse (> 20 beats per minute) or decrease in blood pressure (> 20 mm Hg systolic or > 10 mm Hg diastolic) Uncontrollable bingeing and purging |

Patients who need professional supervision and structure to eat, gain weight, or avoid disordered behaviors, or for whom outpatient treatment has not been successful, may require residential care (i.e., constant care), partial hospitalization (e.g., day program), or intensive outpatient care (e.g., partial day, nondaily; Figure 1).3,20,33,60 Requiring feeding without a patient's consent should be guided by legal standards and by experts in specialty centers.

BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), which can be applied in person or by self-help or guided self-help, is an evidence-based treatment for adults that has also demonstrated effectiveness for youth.25 CBT targets the overvaluation of body shape and weight and subsequent cycles of dietary restraint, disinhibited eating, and compensatory behaviors1,17 (Table 73,5,17,24,34,36–38). Direct engagement with a patient's social support system may be critical because eating is considered a social activity.1 Treatment of less common eating disorders is not discussed because of limited data.

| Psychotherapy modality | General treatment principles | Typical treatment timelines |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive behavior therapy | Individual-focused therapy that targets the patient's distorted cognitions and associated problematic eating behaviors Identify psychological issues and determine how dietary/emotional factors affect behaviors May involve meal planning, challenging dysfunctional automatic thoughts (e.g., all-or-nothing thinking), behavior experiments, exposure to feared foods, and relapse prevention Completion of food records may be helpful in binge-eating disorder Recommended for use in patients with bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder | Weekly sessions over four to 12 months depending on condition Early stages may include sessions two times per week Can be completed in individual or group environments |

| Family-based therapy | Treatment plan focused on behaviors and education within a family unit. Family members are not to blame, should conceptualize and frame the eating disorder as separate from the person, and are vital to therapeutic success by “uniting” against the disorder. Phase 1: empowers parents in promoting healthy eating behaviors and to restore patient's weight Phase 2: autonomy in feeding is gradually shifted back to patient Phase 3: facilitates improved family communication and independence Recommended for use in adolescents and young adults with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa | Occurs over six to 12 months, consisting of 18 to 20 sessions |

| Self-guided treatment | Utilizes cognitive behavior therapy principles in self-driven format Self-monitoring of eating behaviors and inward reflection of their underlying causes Components of treatment include nutrition education about healthy eating and development of coping strategies to triggering situations and to decrease the risk of relapse Treatment can be delivered via internet, mobile application, or written material Recommended for use in bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder | Typical timeline: self-paced course, between four and 12 months Consider supplementing self-help programming with brief, in-person sessions Progress to alternative therapy if ineffective after four weeks |

| Specialist supportive clinical management | Psychoeducation model based on “gentle coaching” Patient-driven therapy founded on therapeutic relationship Education provided on mutually agreed-upon symptom targets Goal-directed therapy to decrease these symptoms Aims to link symptoms and abnormal eating behaviors Recommended for use in adults with anorexia nervosa; low-quality studies suggest benefit in bulimia nervosa | Typically consists of 20 or more weekly sessions spread out over one year |

Anorexia Nervosa. Family-based therapy is recommended as a first-line treatment for youth and some young adults.3,34,39 Studies of family-based therapy demonstrate higher remission rates and increased weight gain compared with individual therapy.34,36,39 Family-based therapy empowers parents to play a vital role in facilitating patients' weight gain before progressively returning control to the patient.3 Short hospitalizations for medical stabilization followed by family-based therapy or outpatient programs have similar outcomes as prolonged hospitalization32,40; therefore, the safest, least intensive treatment environment is recommended.41 In adults, CBT, family-based therapy, focal psychodynamic psychotherapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and specialist supportive clinical management have demonstrated effectiveness and can be implemented based on patient preferences.17,34,42,43

Binge-Eating Disorder. Meta-analytic data support treatment with CBT and self-guided therapy.38 In-person CBT more effectively decreases binge eating and therapy dropout than self-guided CBT at six months and confers markedly better outcomes than weight-loss therapies.38 Patients who exhibit a rapid decrease in binge-eating behaviors (e.g., by two-thirds) in the first month of treatment are more likely to have sustained remission, regardless of treatment modality, than patients who do not.44

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Pharmacotherapy should not be pursued as a monotherapy for eating disorders,17,34 but it may be a worthwhile adjunctive therapy, specifically in the presence of co-occurring mental health conditions.45,46 Patient sensitivities or fear of weight gain limits tolerability.20,46,47 Medications that affect electrolytes or heart rate, or that prolong the corrected QT interval, should be prescribed with caution.20,45,46

Anorexia Nervosa. There are no medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat anorexia nervosa. A recent multicenter, randomized controlled trial of 10 mg of olanzapine (Zyprexa) demonstrated modest benefit in inducing weight gain and appetite without metabolic syndrome components. 48 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed despite a weak evidence base consisting of few randomized controlled trials.46,47 Bupropion (Wellbutrin) is contraindicated in anorexia and bulimia nervosa because of the risk of seizure.40,46,47

Bulimia Nervosa. Fluoxetine (Prozac) is an FDA-approved treatment in adolescents and adults; dosages titrated to 60 mg per day resulted in substantial decreases in bingeing and purging compared with placebo and lower dosages.36,46 Studies of other SSRIs have found benefit at high dosages; however, high-dose citalopram (Celexa) and escitalopram (Lexapro) increase the risk of corrected QT interval prolongation.46 Topiramate (Topamax) may decrease bingeing and purging behaviors, but it may also limit appetite cues, potentially complicating treatment.46,49

Binge-Eating Disorder. Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse), approved by the FDA for binge-eating disorder, and topiramate decrease binge-eating episodes and may lead to weight stabilization or loss.37,46,50 SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and appetite suppressants may decrease binge eating, with a variable effect on weight.46

BONE HEALTH

Among patients with weight loss, weight restoration is important for the recovery of bone mineral density.3,20,47,51 However, weight restoration in females without resumption of menses indicates ongoing compromise.51 Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (i.e., anovulation linked to weight loss, excessive exercise, or stress) has been reviewed recently.31,52

Hormonal contraceptives have not been associated with improved bone mineral density and may mask natural resumption of menses, an important recovery marker, but effective contraception should be offered to patients who want to prevent pregnancy.31,52 Short-term transdermal 17-beta estradiol (e.g., 100-mcg patch, or incremental doses if bone age is less than 15) avoids first-pass liver metabolism and may be given with cyclic oral progestin (e.g., medroxyprogesterone [Provera], 2.5 mg per day, 10 days per month) to improve bone health after six to 12 months of nonpharmacologic therapy.17,52,53 Resumption of menses, which may take longer than one year to achieve, is associated with return to pre-illness (or slightly higher) weight and a serum estradiol measurement greater than 30 pg per mL (110.13 pmol per L).54

SPORTS PARTICIPATION

Participation in athletics may interfere with the healing process by allowing untreated disordered behaviors to continue. Therefore, participation requires considering a patient's clinical and psychosocial context and their ability to increase nutritional consumption to compensate for additional energy expenditure. Shared decision-making between the athlete, treatment team, and caregivers should prioritize recovery. One decision tool for patients with female athlete triad (i.e., menstrual dysfunction, low energy availability, and decreased bone mineral density) is shown in eTable B, which categorically restricts sports participation with disordered eating and a BMI of less than 16 kg per m2 or purging more than four times per week.55

| Risk factors | Magnitude of risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk = 0 points each | Moderate risk = 1 point each | High risk = 2 points each | |

| Low energy availability with or without an eating disorder | No dietary restriction | Some dietary restriction; current or previous eating disorder | Meets DSM-5 criteria for current or previous eating disorder |

| Low BMI or expected weight | BMI = 18.5 kg per m2 or more, 90% or more of expected weight, or weight stable | BMI = 17.5 kg per m2 to less than 18.5 kg per m2, less than 90% of expected weight, or monthly weight loss of 5% to less than 10% | BMI = less than 17.5 kg per m2, less than 85% of expected weight, or monthly weight loss of 10% or more |

| Delayed menarche | Menarche at younger than 15 years | Menarche at 15 years to younger than 16 years | Menarche at 16 years or older |

| Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (current or previous) | More than nine menses in 12 months | Six to nine menses in 12 months | Fewer than six menses in 12 months |

| Low bone mineral density† | Z-score = −1.0 or more | Z-score = −1.0 to less than −2.0, particularly in patients involved in weight-bearing sports | Z-score = −2.0 or less |

| Stress reaction or fracture | None | One | Two or more, or one or more high-risk fractures (e.g., trabecular site such as femoral neck, sacrum, or pelvis) |

| Cumulative risk | ________ | ________ | ________ |

| points + | points + | points | |

| ________= Total score | |||

OTHER TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

Weight restoration in patients with anorexia nervosa resolves most associated medical complications.20 School-aged patients may benefit from a 504 plan allowing meal accommodations (e.g., with a trusted adult) and periodic snacking. Caregivers should be empowered to monitor social media use and restrict access to pro-anorexia (proana) and pro-bulimia (pro-mia) websites. Attention-deficit symptoms may emerge with poor nutrition and resolve with weight restoration; stimulant use may cause weight loss and decrease appetite cues, impeding treatment. Patients who purge should seek regular dental care.17,24 Family members may benefit from individual or family-based counseling.17

Markers of Recovery

Restoring the patient's healthy relationship with food involves fostering cognitive flexibility around eating, eliminating harmful behaviors, and reducing body dissatisfaction and overvaluation of shape and weight.20 Among patients with weight loss, restoration of weight and menses (if applicable) is a critical first step in improving overall bio-psychosocial functioning.3

Prevention

For patients of all weight strata, caregivers and clinicians should support healthy, sustainable lifestyle choices such as optimizing family meals, physical activity, and consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and water, while limiting sweetened beverages, refined carbohydrates, and entertainment-based screen time.5 Caregivers should be counseled to refrain from commenting on dieting or on weight or other appearance-related attributes. Body dissatisfaction should not serve as the impetus for weight-loss efforts; instead, health and specific health-related goals should be emphasized.5 Acceptance of larger body size may be an important therapeutic target.5 If necessary, neutral terms such as “weight” or “BMI” are less stigmatizing than “fat,” “large,” or “obese.”56 Weight-based victimization should be assessed and confronted because it may contribute to eating pathology and weight gain.5,16,57 Online resources are available for family members (https://www.feast-ed.org), clinicians (https://www.aedweb.org), and patients with disordered eating (https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org).

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Harrington, et al.58 ; Williams, et al.24 ; and Pritts and Susman.59

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the MeSH function with the key phrases eating disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and one of the following: diagnosis, evaluation, management, or treatment. The reference lists of specific cited references were searched for additional studies of interest. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews published after January 1, 2015. Other queries included Essential Evidence Plus and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Search dates: April through June 2020.

The authors thank Arielle Pearlman for her editorial assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; the Departments of the Air Force, Army, Navy, or the U.S. military at large; the Department of Defense; or the U.S. government.