Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(12):727-736

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a heterogeneous group of conditions related to specific biologic and cellular abnormalities that are not fully understood. Psychological factors do not cause IBS, but many people with IBS also have anxiety or depressed mood, a history of adverse life events, or psychosocial stressors. Physicians must understand the fears and expectations of patients and how they think about their symptoms and should also respond empathetically to psychosocial cues. Anxiety related to the unpredictability of symptoms may have a greater effect on quality of life than the symptoms themselves. Patients in generally good health who have ongoing or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms and abnormal stool patterns most likely have IBS or another functional gastrointestinal disorder. Patients who meet symptom-based criteria and have no alarm features may be confidently diagnosed with few, if any, additional tests. Patients may not completely understand the diagnostic process; asking about expectations and carefully explaining the goals and limitations of testing leads to more effective care. There is no definitive treatment for IBS, and recommended treatments focus on symptom relief and improved quality of life. Trusting patient-physician interactions are essential to help patients understand and accept an IBS diagnosis and to actively engage in effective self-management.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), although common, is not completely understood and is often unrecognized and underdiagnosed.1 Patients may not accept the diagnosis, believing that IBS is a label that connotes a psychological disorder or implies that a cause for their distress has not yet been found.2,3 Primary care physicians and specialists may hesitate to share the diagnosis for the same reasons or, believing IBS to be a diagnosis of exclusion, may be reluctant to make the diagnosis without exhaustive testing.4,5

Most individuals with IBS have relatively mild or intermittent symptoms and can be treated with reassurance, education, dietary advice, and the occasional use of medications.6–8 As with other chronic conditions affecting patients who may have coexisting psychological issues, the patient-physician relationship is particularly crucial for effective long-term management.9 Physicians must elicit the specific concerns and expectations of patients and understand the ways in which IBS affects patients' lives and the diverse explanatory models that patients use when describing their illness.2,10–14 Physicians should be able to discuss and describe IBS and its management in ways that are consistent with patients' beliefs.

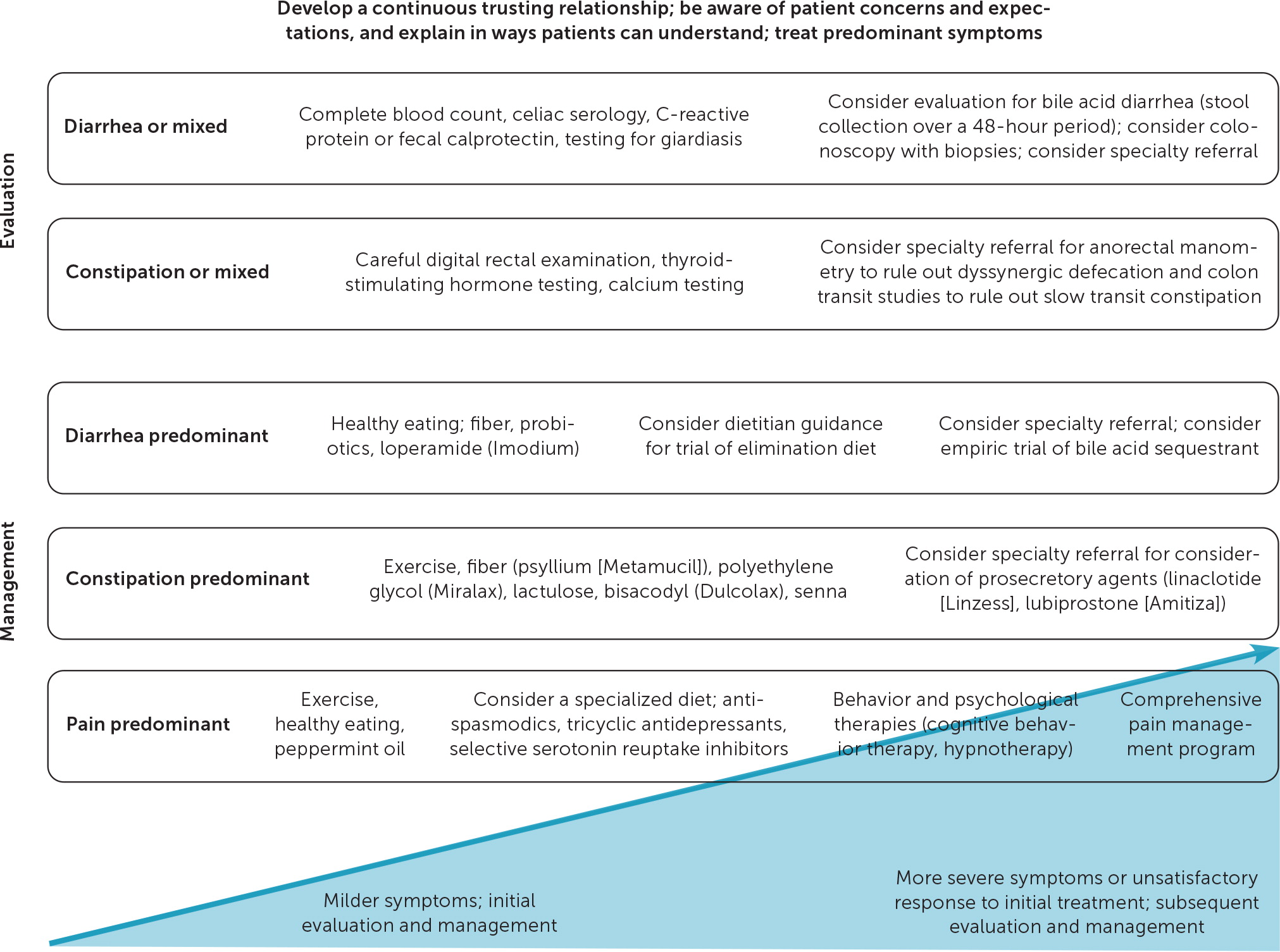

The following questions provide a framework for physicians to better understand the etiology and clinical presentations of IBS, to be more aware of patient perspectives, and to recognize and confidently diagnose and treat the condition. These questions outline the steps necessary for developing the continuous trusting interactions necessary for helping patients accept the diagnosis and actively engage in effective self-management (Table 12,3,11,14–22). Figure 1 outlines the principles of the evaluation and management of IBS.7,8,14,15,23–29

| Recommended | Likely effective | Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Express empathy and be alert for psychosocial cues | Acknowledging that the patient's explanations and symptoms are real; ask how symptoms affect daily life (e.g., “I am sorry you are feeling this way. I can see that the pain has affected your life.”) Be alert for empathic opportunities; many patients provide cues to emotional or social problems; acknowledge and address psychosocial concerns | Dismissing symptoms (e.g., “There is nothing wrong with you.”) Missing or failing to engage with cues and addressing only symptoms; this may further somatization in patients |

| Solicit the patient's views about causes and triggers of symptoms | Asking open-ended questions (e.g., “Can you tell me what you think is causing your symptoms?” or “What do you think triggers your symptoms?”) | Asking closed-ended questions (e.g., “Do you think your pain is caused by eating?”) |

| Assess the patient's views on the connection between their symptoms and stress | Emphasizing that gastrointestinal abnormalities may disproportionately affect patients who are simultaneously experiencing stressful life events may be a more effective and acceptable starting point for discussions | Focusing on individuals with certain personality types who are susceptible to IBS may be less acceptable to patients |

| Understand the patient's concerns about symptoms and expectations from the visit | Asking open-ended questions (e.g., “Tell me a little about what you are expecting from this consultation.” or “I'm hearing that you have been experiencing pain for many years. Could you tell me about why you want to see me today?”) | Using judgmental statements (e.g., “I am not sure I can help you. You have been to so many doctors already.”) |

| Help the patient understand and accept the diagnostic process | Although abnormal findings are rare (abdominal tenderness or a palpable colon are common findings in general), the physical examination is important | Neglecting to perform a physical examination even if no abnormal findings are expected Performing tests only for reassurance |

| Understand the patient's expectations from treatment(s) | Acknowledging the patient's frustration with multiple treatments that have not been helpful Ask probing, open-ended questions (e.g., “What would be a tolerable pain level that we can try to achieve?”) | Imposing a treatment plan (e.g., “My plan is to refer you to a pain specialist and a psychiatrist.”) |

| Assess the patient's understanding of the education you provided | Having patients reiterate what they have heard (e.g., “I provided you with a lot of information today. I hope that it was understandable and makes sense to you. Can you tell me what you have understood so far?”) | Using a unilateral flow of information (e.g., “I hope you understood all the things we discussed today and that you implement the suggestions I gave you.”) |

| Enlist the patient as an active participant in their own IBS symptom management | Suggesting that the patient keep a diary of symptoms for three to four weeks; take time to review and discuss in detail at the return visit | Prescribing treatments in which the patient is a passive recipient |

| Leverage the benefits of a continuous caring physician-patient relationship | Scheduling a return visit | Assuming that patients who do not return have responded to treatment or are now symptom free |

What Is the Current Understanding of the Pathophysiology of IBS and Its Relationship to Psychological Concerns?

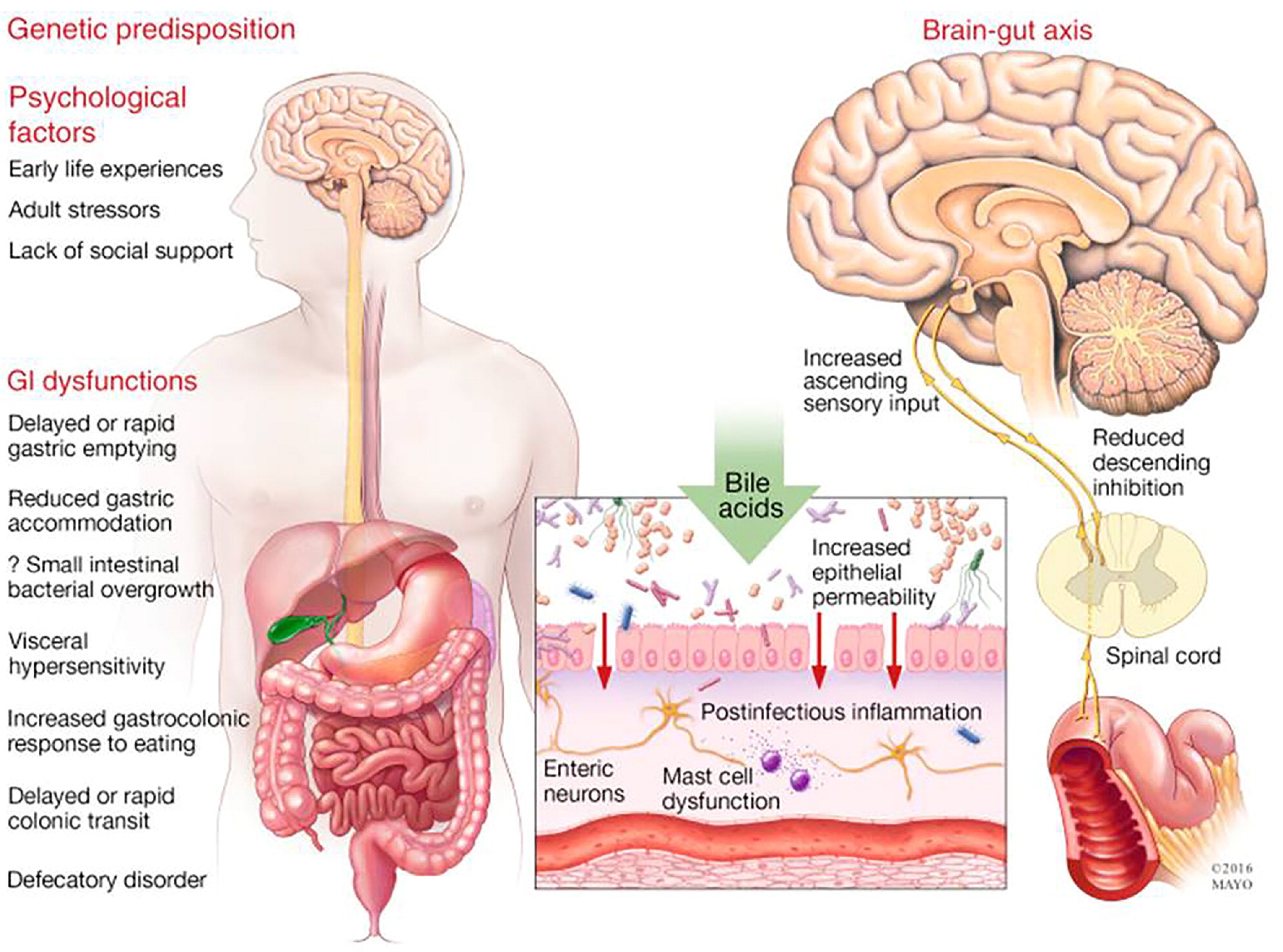

IBS is a heterogeneous group of conditions that is best understood in the context of the biopsychosocial model. Several different biologic and cellular abnormalities may cause similar disturbances in gut-brain modulation over time, especially in susceptible individuals, resulting in pain and abnormal stool patterns23 (eFigure A). Other functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders and chronic pain syndromes, including fibromyalgia, fatigue, or chronic pelvic pain, often coexist with IBS.13 Many people with IBS may also have coexisting anxiety or depressed mood, a history of adverse life events, or psychosocial stressors.30 Although stress may alter colonic motility and sensation, psychological factors may be the result of, rather than the cause of, IBS symptoms.14

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Several pathologic processes that trigger IBS in certain individuals have been identified, such as immune activation following gastroenteritis (postinfectious IBS), altered permeability of the bowel wall caused by certain foods, or alterations of gut microflora caused by medications. Over time, sensory (afferent) nerves from the gut to the brain and regulatory (efferent) nerves from the brain to the gut are activated, leading to heightened peripheral and central pain perception and altered bowel motility, transit, and function.23

Many patients with IBS and other functional GI disorders have coexisting psychological factors.30 These factors may predispose patients to IBS, precipitate IBS, or perpetuate symptoms.33 For instance, patients who develop postinfectious IBS sometimes report major life stressors at the time of the initial infection.34 Patients with chronic stress and low energy may develop more persistent symptoms or more frequent exacerbations.10,14 Patients with IBS that significantly affects normal functioning are more likely to be anxious about specific symptoms than to have generalized anxiety.16 The unpredictability and potential embarrassment related to abnormal bowel movements, the uncertainty of which foods or circumstances might trigger symptoms, and the feeling of not being in control may result in fear and avoidance behaviors over time.35

What Symptom Patterns Suggest Possible IBS?

Patients in generally good health who have ongoing or recurrent GI symptoms and abnormal stool patterns likely have IBS or another functional GI disorder.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Patients with IBS typically have chronic, recurring abdominal pain associated with disordered bowel movements, as well as abdominal bloating or distention. They may experience urgency or excessive straining to defecate, a sense of incomplete evacuation, or mucus with stools; they typically do not have nocturnal stools36 (Table 27,13,24,36,37). Clinical presentations may be highly variable among individuals or in the same individual at different times.13 For many patients, pain is related only minimally to bowel habits.37 Some patients may have continuous symptoms, whereas others experience flare-ups that last for only a few days with months or years between episodes.32

| Recurrent abdominal pain, with onset more than 6 months earlier, occurring on average at least 1 day per week in the past 3 months, and associated with 2 or more of the following features |

| Related to defecation (may be improved or worsened) |

| Associated with a change in the frequency of stool |

| Associated with a change in the form or appearance of stool |

| Additional symptoms support the diagnosis of IBS |

| Abnormal stool frequency (more than 3 times per day or less than 3 times per week) |

| Abnormal stool form (loose and watery or lumpy and hard) |

| Abnormal stool passage (urgency, straining, feeling of incomplete evacuation) |

| Passage of mucus (white material) |

| Abdominal bloating |

| Abdominal distention |

| Absence of nocturnal stools |

| Subtypes of IBS* |

| IBS with predominant diarrhea: > 25% of bowel movements are Bristol Stool Scale type 6 or 7, and < 25% are type 1 or 2 |

| IBS with predominant constipation: > 25% of bowel movements are Bristol Stool Scale type 1 or 2, and < 25% are type 6 or 7 |

| IBS with mixed symptoms of constipation and diarrhea: > 25% of bowel movements are Bristol Stool Scale type 1 or 2, and > 25% are type 6 or 7 |

| Unclassified IBS: bowel movements cannot be accurately categorized as one of the three subtypes |

Among patients with functional GI disorders, approximately 45% improve after several years, whereas 30% develop new symptoms, and 25% have no change in symptoms.32

What Are the Concerns and Expectations of Patients with Symptoms of IBS Who Seek Care from Family Physicians?

Patients may have goals or fears that they do not articulate and that may not occur to physicians.38 The visit is more likely to be helpful if physicians understand the ways in which patients try to make sense of their symptoms and how those symptoms affect patients' lives.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Patients may seek help with abdominal pain, abnormal stool patterns, or GI symptoms during a visit for other concerns. They may have had a previous evaluation for the same symptoms but did not receive or do not recall a diagnosis, or they did not understand or agree with the diagnosis. Disappointed with prior visits or treatments, these patients may be seeking additional recommendations, alternative treatments, or specialty referral.3,11,16,17

Some patients with IBS may experience chronic stress, low energy, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and sleep disturbances; these symptoms may have a greater effect on daily functioning than the GI symptoms themselves.10 Patients often provide cues about psychosocial difficulties and a willingness to explore the role of psychological factors in their illness but may perceive that physicians disregard or only superficially acknowledge their concerns.3,18 Patients may ultimately be so discouraged that they stop seeking care, leading physicians to incorrectly assume that the IBS is no longer a problem.11

A subset of patients with more severe distress, a pattern of multiple urgent visits, and repeated testing for disparate symptoms may have somatization disorder.40 These individuals, who are often resistant to any suggestion that their symptoms might be related to psychological factors, have generally poorer outcomes.41 Although not typical of patients with IBS, interactions with these patients are more challenging and may reinforce inappropriate biases held by some physicians regarding patients with functional GI disorders.

What Are the Current Recommendations for Testing in Patients Presumed to Have IBS?

| Abdominal mass Extreme diarrhea symptoms (large volume, bloody, nocturnal, progressive pain, does not improve with fasting) Fever Gastrointestinal bleeding (overt: melena or hematochezia; occult: anemia or fecal occult blood on testing) Jaundice Lymphadenopathy New-onset symptoms in patients 55 years and older* Symptoms of chronic pancreatitis† Symptoms of gastrointestinal cancer or a family history of the disease‡ Symptoms of ovarian cancer or a family history of the disease§ Tenesmus (rectal pain or feeling of incomplete evacuation) Unintentional weight loss |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before testing, the physician should inquire about medications and substances the patient is using that may cause IBS-like symptoms. Use of metformin, magnesium-containing antacids, artificial sweeteners (mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol), and antibiotics and excess use of alcohol are common and may cause loose stools.44 Opioids, calcium channel blockers, and diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and other over-the-counter medications with anticholinergic effects may cause constipation.

Limited testing, including serologic testing for celiac disease; C-reactive protein measurement or fecal calprotectin testing for inflammatory bowel disease; and stool antigen testing for giardiasis, especially in patients with chronic diarrhea, is reasonable. 25,26 Exhaustive testing, particularly colonoscopy, is not necessary before diagnosing IBS.43 Patients diagnosed with IBS have less than a 5% likelihood of receiving an alternative diagnosis in the future.45 Even when alarm features are present, the diagnostic yield of additional testing is relatively low.46 Table 4 provides information about the initial evaluation of patients with presumed IBS.4,7,8,13,25–27,43

| Conditions with similar symptoms | Testing to consider | Clinical features/comments |

|---|---|---|

| Celiac disease | Tissue transglutaminase and total immunoglobin A (to rule out immunoglobin A deficiency; if present, follow up with deaminated gliadin)25,26 Positive findings on serologic testing should be confirmed with biopsy | Patients cannot be on a gluten-free diet at time of testing; serologic tests and biopsies may be falsely negative (absence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 can rule out celiac disease) Consider in patients with diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, bloating, distention, and flatulence or if local prevalence of celiac disease is > 1%7,8 Extraintestinal symptoms include anemia, dermatitis herpetiformis, oral lesions, osteoporosis, or osteopenia |

| Colorectal cancer | Complete blood count26 Colonoscopy usually not necessary | Fear of cancer is a common concern for patients with IBS symptoms, and this should be discussed Consider in patients 55 years and older who have alarm features (e.g., family history, abdominal pain, abdominal mass, weight loss), if the patient is due for routine screening, or if colonoscopy is otherwise indicated 4,43 |

| Dyssynergic defecation (pelvic floor dysfunction) | Perineal and rectal examination (if negative, further testing, such as anorectal manometry, can be deferred)27 | Incomplete evacuation, straining with defecation, manual removal of stool, history of sexual or physical abuse |

| Functional abdominal distention/functional abdominal bloating | Testing similar to IBS | Functional gastrointestinal disorder distinct from IBS, but overall management is similar Subjective symptoms of recurrent abdominal pressure with objective increases in abdominal girth (functional abdominal distention) or sensation of trapped gas (functional abdominal bloating), fewer stool abnormalities, more likely related to abdominal wall distention than to retained gas13 |

| Functional diarrhea | Testing similar to IBS | Functional gastrointestinal disorder distinct from IBS, but overall management is similar Pain and bloating are not predominant symptoms, as in IBS13 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease) | C-reactive protein or fecal calprotectin If positive, colonoscopy with biopsies and ileoscopy 26 | Family history; abdominal pain and tenderness, perianal disease or fissuring, skin manifestations |

| Medications commonly associated with constipation (secondary constipation) | Medication history; usually no further testing necessary | Calcium-containing antacids, iron supplements, anticholinergics, opioids |

| Medications commonly associated with diarrhea; alcohol use | Medication and substance use history; usually no further testing necessary | Nonosmotic or stimulant laxatives, magnesium-containing antacids, sugar alcohols (mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol), antibiotics, metformin, alcohol abuse |

| Metabolic abnormalities commonly associated with constipation (secondary constipation) | Thyroid-stimulating hormone, chemistry panel, A1C, serum magnesium | Hypothyroidism, diabetic neuropathy, hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia can cause constipation13 |

| Noninvasive small bowel parasite (e.g., Giardia) | Stool test for giardiasis26 | Testing for other ova and parasite diseases not routinely indicated unless specifically indicated |

| Opioid-induced constipation | Medication history, review of Prescription Drug Monitoring Program database, review of electronic health record; usually no further testing necessary | May coexist with constipation-predominant IBS or functional constipation Straining, incomplete evacuation, hard/lumpy stools, manual removal of stool Patients may also report dysphagia, reflux, nausea, bloating13 Assess for opioid use disorder, refer for treatment if needed |

IBS has traditionally been classified as being diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D), constipation-predominant (IBS-C), or mixed (IBS-M), but many patients have symptoms that overlap among various subtypes (Table 27,13,24,36,37) or that shift among different stool patterns within a few weeks or less.37 The Bristol Stool Scale is the best method to ensure consistent descriptions of bowel movements (see Figure 1 in a previous AFP article), with testing and treatment guided by the symptoms of greatest concern to the patient.

Although abnormal findings are uncommon, the physical examination builds trust, conveys thoroughness and empathy, and cannot be neglected.14,20 In patients with chronic constipation, a digital rectal examination may provide clues to pelvic floor dysfunction (dyssynergic defecation27; see Table 3 in a previous AFP article for a description of this examination). Other findings that warrant further evaluation include jaundice, ascites, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, abdominal masses, or abdominal wall pain.

No tests definitively rule in IBS. Biomarkers specific to some underlying conditions have been developed but are not widely available or standardized and are not recommended for routine use in primary care. However, they should be considered in patients with more severe symptoms or if conservative treatments fail.28 In particular, early testing for bile acid diarrhea (which may be at least as prevalent as celiac disease) may lead to definitive treatment and decrease overall health care use.29 eTable A summarizes additional testing options in patients who have more severe symptoms or unsatisfactory response to initial treatment.

| Conditions with similar symptoms | Testing to consider | Clinical features/comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bile acid diarrhea | SeHCAT where available, serum C4, FGF19, 48-hour fecal bile acidsA1 Empiric trial of a bile acid sequestrant (e.g., colesevelam [Welchol], colestipol [Colestid], cholestyramine [Questran]) is an alternative to testing but is limited by patient compliance and tolerance; some authorities recommend with caution,A2 whereas others recommend againstA3,A4 | Consider if diarrhea developed following cholecystectomy Community prevalence of bile acid diarrhea may be greater than that of celiac disease; testing initiated earlier in the evaluation process may result in decreased health care utilizationA5 |

| Carbohydrate malabsorption (e.g., lactose, fructose) | Breath tests, trial of food avoidance | Can also cause a fatty malabsorptive diarrhea Inquire about food triggers, family historyA6,A7 |

| Dyssynergic defecation (pelvic floor dysfunction) | Referral for expert perineal and rectal examination and anorectal manometryA8 (anorectal manometry may be required to justify insurance coverage of pelvic floor retraining or therapy) | Incomplete evacuation, straining with defecation, manual removal of stool, history of sexual or physical abuseA9 |

| Functional dyspepsia | Helicobacter pylori testing (stool antigen testing is most cost-effective, urea breath tests are more accurate but more expensive, serologic tests are least accurate) If patient is older than 55 years or has alarm features, esophagogastroduodenoscopy is indicated | IBS and functional dyspepsia may coexist; both may cause postprandial discomfort, bloating, and distention that are relieved by bowel movementA1,A10,A11 |

| Microscopic colitis | Colonoscopy with multiple biopsies (even if mucosa appears normal) and ileoscopy | Consider in patients with chronic unexplained watery diarrheaA7 |

| Nonceliac gluten sensitivity | Tissue transglutaminase IgA, total IgA, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with duodenal biopsy to rule out celiac disease | Gluten food trigger, can have systemic symptoms similar to celiac diseaseA12 |

| Pseudomembranous colitis (Clostridioides difficile) | Stool nucleic acid amplification tests for toxin genes (only diarrheal stools should be tested to avoid false-positive results) | Antibiotic use, patient is in a health care environment, patient is immunocompromisedA7 |

| Slow transit constipation | Colonic transit study (consider only after ruling out dyssynergic defecation) | Rare condition, false-positive results are not uncommon |

| Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth | Lactulose hydrogen breath testing (appropriate only in patients with risk factors for this condition) | Risk factors for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Structural abnormalities (small bowel diverticula, strictures, surgical blind loops, or ileocecal valve resection) Disordered motility (scleroderma, type 1 diabetes mellitus, opioid use) Acid suppression (chronic proton pump inhibitor use, achlorhydria, gastric resection)A7,A9 |

Testing performed primarily for reassurance or to allay anxiety about cancer or other missed diagnoses may be counterproductive, often reinforcing patients' fears of disease, lessening their confidence in the diagnosis, and even leading to more testing.21,22 A diagnosis delivered in clear, unambiguous language can be as reassuring as additional testing.5,6

What Is the Most Appropriate Initial Treatment for Patients with Presumed IBS?

Individuals with mild to moderate IBS are more likely to seek care for acute symptom flare-ups than for ongoing treatment of chronic symptoms.17 Reassurance and advice, with medications used as needed, are often all that is necessary. To be effective, it is essential that family physicians develop continuous trusting relationships with patients and foster realistic expectations.9,14 Initial management strategies are summarized in Table 5.7,8,28,42,47–55

| Diet General Patients should focus on eating in moderation, getting adequate but not excessive fiber, decreasing fatty and spicy foods, and avoiding caffeine, soft drinks, carbonated drinks, and artificial sweeteners before considering more restrictive elimination diets FODMAP-restricted diet Shows promise for IBS management, but questions remain regarding long-term safety, effectiveness, and practicality; if this diet is initiated, patients should be supervised by an experienced dietitian7,28,47,48 Gluten-free diet Patients with celiac disease derive clear benefit; some patients without celiac disease markers seem to benefit (wheat contains gluten and high levels of fructans; reduction of fructans may partly explain the benefit in patients with IBS) Long-term effects of a gluten-free diet on microbiome and general nutrition are uncertain; strictly adhering to this diet is difficult and expensive Recommended only for patients with proven celiac disease47 Exercise Regular daily exercise decreases symptoms of IBS and chronic constipation47 Fiber Soluble fiber (psyllium [Metamucil]): 25 to 30 g daily has a small benefit for some patients with IBS but can worsen bloating in others7,47 Insoluble fiber (bran, methylcellulose, polycarbophil [Fibercon]): 2 heaping teaspoons daily was of no benefit to patients with IBS; some benefit for chronic constipation7,47 All fiber should be increased gradually to minimize bloating, distention, flatulence, and cramping Worsening of gas and bloating with fiber supplementation may also suggest underlying dyssynergic defecation (pelvic floor dysfunction)7,49,50 Osmotic laxatives Polyethylene glycol (Miralax): 17 g once daily; this is the best studied osmotic laxative and is most effective for chronic constipation, with slight improvement in stool frequency in IBS-C7,8,51 Other osmotic laxatives include lactulose, sorbitol, and mannitol Probiotics Probiotics, especially Bifidobacterium infantis, improve bloating, flatulence, and pain in IBS and may also help chronic constipation47 Antispasmodics Dicyclomine: 20 mg 4 times daily (maximum 40 mg four times daily) 30 minutes before meals; moderately effective for IBS7,8,42,47 Hyoscyamine extended release (Levbid), 0.375 to 0.75 mg 2 times daily (maximum 1.5 g per day); moderately effective for IBS42,47 Hyoscyamine (Levsin), 0.125 to 0.25 mg every 4 hours as needed (maximum 1.5 mg per day; 30 minutes before meals); moderately effective for IBS Peppermint oil: 200 to 750 mg 2 or 3 times daily; moderately effective for IBS7,8,42,47 STW 5 herbal preparation (proprietary blend of 9 herbs, available over the counter): 20 drops (30 minutes before meals); antispasmodic and prokinetic actions47 Opioid agonists Diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil) has not been studied in IBS Loperamide (Imodium): 2 to 4 mg up to 4 times daily; decreases colonic transit and increases water absorption, improves many IBS-D symptoms, including urgency and stool frequency47 Older clinical trials were small but demonstrated improved overall response52,53 Serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist Ondansetron (Zofran): 4 mg up to 3 times daily (many patients need to use only once daily or less); improves urgency and frequency of loose stools in IBS-D and postinfectious IBS Less improvement of pain but two-thirds of patients report adequate relief; some of the benefit may be related to relief of coexisting heartburn and postprandial pain/dyspepsia54 Widely available, inexpensive, excellent safety profile over many decades (alosetron [Lotronex], a more potent serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist approved only for more severe IBS-D in women, has significant safety concerns) Antidepressants (gut-brain modulators) Amitriptyline: 10 to 50 mg at bedtime (increase by 10 mg every 1 to 2 weeks) and other tricyclic antidepressants; effective for overall symptom relief in IBS-D and other functional gastrointestinal disorders7,8,47 Histaminergic properties are moderately sedating, and anticholinergic properties are moderately constipating55 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g., duloxetine [Cymbalta]): strong evidence for benefit in several chronic pain disorders but not currently studied in IBS7,8 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: slight overall improvement, probably related to relief of central and visceral hypersensitivity and psychological distress; may help constipation7,8 |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Reassurance regarding the generally benign course of IBS must be approached with care and sensitivity.6 If reassurance is perceived as perfunctory or dismissive, patients may subconsciously overemphasize the frequency and severity of symptoms,39,56 in turn causing physicians to escalate further attempts at reassurance, which may be misinterpreted as implying that nothing is wrong.3,57

Patients may sometimes be dissatisfied with how physicians explain the relationship between IBS symptoms and stress, which may lead to a perception that the physician is not taking the symptoms seriously.2,3,19 Many physicians focus on the maladaptive responses of individuals to stress,38 whereas patients may consider stress as a discrete event or set of circumstances over which they have little, if any, control.11,12 Consequently, explaining that stressful life events may worsen gastrointestinal symptoms may be more acceptable than explaining that patients with certain personality types may be predisposed to developing IBS.2,39

Interventions should focus on the most troublesome symptoms or their triggers and on improving quality of life.7,8,35 All IBS interventions appear to be successful some of the time, but their exact effectiveness cannot be measured or predicted in individual patients because symptoms wax and wane. Moreover, in some trials, as many as 50% of patients receiving only placebo reported adequate symptom relief.58,59

Many patients associate eating a meal or specific foods with the onset of their symptoms and thus have tried eliminating certain foods. This has limited success because true food intolerance is rare.7,8 Gluten-free diets should be instituted only for clear indications. Diets that restrict fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (for examples, see Table 5 in a previous AFP article) may sometimes be effective, but they typically require the guidance of an experienced dietitian.7,8

Soluble fiber (ispaghula husk, oat bran, psyllium [Metamucil]) may help some patients, but insoluble fiber (wheat bran, whole grains, methylcellulose [Citrucel], polycarbophil [Fibercon]) may increase pain or bloating.7,8 Probiotics may have a favorable effect on the intestinal microbiome and improve bloating, flatulence, and pain, but the overall level of evidence is very low.7,8

Older, traditional medications are generally inexpensive and have been used safely and successfully for decades as first-line therapies, but most, particularly antispasmodics, have never been rigorously evaluated. Osmotic laxatives (for IBS-C) or antidiarrheals (for IBS-D) may improve stool frequency. Antispasmodics, peppermint oil, and other herbal preparations may help relieve pain.7 Ondansetron (Zofran) can be used as needed to decrease urgency in IBS-D.54

Tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which can be described to patients as gut-brain modulators, also help relieve pain but may cause adverse effects. The overall benefit of these medications may be somewhat greater than other medications because they help treat the anxiety related to unpredictable bowel patterns.55 Persistent anxiety may respond to cognitive behavior therapy or hypnotherapy.7,8

For patients with more severe, debilitating, or progressive symptoms or in whom the diagnosis is less certain, family physicians should work with specialists for further evaluation and treatment. Several medications specifically approved for IBS-D and IBS-C may be considered in patients who do not respond to standard first-line therapies, but their use is often limited by adverse effects and cost.7,8

| Serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist (IBS-D) Alosetron (Lotronex): should not be used in women with severe diarrhea, potentially severe adverse effects Ondansetron (Zofran): 4 mg up to 4 times daily; has similar but less robust benefit as alosetron but with an excellent safety profile (Table 5) Serotonin (5-HT4) receptor agonist (IBS-C) Tegaserod (Zelnorm): 6 mg twice daily for adult women younger than 65 years with IBS-C; contraindicated if more than 1 cardiac risk factor; small concern about excess cardiovascular ischemic events Prosecretory agents (IBS-C) Linaclotide (Linzess): 72 mcg daily or 145 mcg daily (for chronic constipation), 290 mcg daily for IBS-C; guanylate cyclase C receptor agonist that induces chloride secretion in the gut and results in looser stools, increased colonic transit, and decreased pain compared with placebo Lubiprostone (Amitiza): 8 mcg twice daily for women with IBS-C, 24 mcg twice daily for men and women with chronic constipation; prostaglandin derivative that induces chloride secretion in the gut and results in looser stools and increased colonic transit and decreased pain compared with placebo; occasional mild nausea occurs Plecanatide (Trulance): 3 mg or 6 mg daily for IBS-C and chronic constipation; analogue of an endogenous guanylate cyclase C receptor agonist that induces chloride secretion in the gut and results in looser stools and increased colonic transit compared with placebo; dose can be titrated to minimize diarrhea Nonabsorbable antibiotics (IBS-D) Rifaximin (Xifaxan): 550 mg by mouth 3 times daily for 14 days; recurrent symptoms can be treated up to 3 times, with 3 months between treatments; improves diarrhea, urgency, bloating, and pain compared with placebo; may act by improving small intestinal bacterial overgrowth No evidence of adverse effects and no increased risk of Clostridioides difficile infection Stimulant laxatives (opioid-induced constipation) Stimulant laxatives (bisacodyl [Dulcolax], cascara, senna) increase motility in chronic constipation but may cause pain and diarrhea; usually reserved for patients with dysmotility disorders or opioid-induced constipation Opioid receptor agonists (IBS-D) Eluxadoline (Viberzi): 100 mg twice daily (75 mg twice daily if higher dose is not tolerated or if the patient has hepatic impairment); novel action on opioid receptors in the gut, relieves diarrhea and pain in IBS-D May cause nausea and headache, and rarely pancreatitis and sphincter of Oddi spasm; contraindicated in patients with history of biliary obstruction, cholecystectomy, pancreatitis, severe hepatic impairment, and in those who drink more than 3 alcoholic beverages per day |

Scheduled return visits, particularly during exacerbations of IBS, are helpful. Discussions should focus on treatment response and coping strategies rather than symptom severity.10,35 Family physicians should help patients have realistic expectations about the limitations of therapy but reassure them that incremental improvements over time are likely.32

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Wilkins, et al.60 ; Hadley and Gaarder61 ; and Viera, et al.62

Data Sources: We searched PubMed and Google Scholar using the terms irritable bowel syndrome, functional gastrointestinal disorders, chronic constipation, abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, either alone or in combination with one another. We examined clinical trials, meta-analyses, review articles, and clinical guidelines, as well as the bibliographies of selected articles. Cochrane and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: April 2020 to April 2021.

The authors thank Michael Camilleri, MD, Clinical Enteric Neuroscience Translational and Epidemiological Research (C.E.N.T.E.R.), Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine, for thoughtful advice and review of the manuscript.