Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):368-374

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Hepatitis A is a common viral infection worldwide that is transmitted via the fecal-oral route. The incidence of infection in the United States decreased by more than 90% after an effective vaccine was introduced, but the number of cases has been increasing because of large community outbreaks in unimmunized individuals. Classic symptoms include fever, malaise, dark urine, and jaundice and are more common in older children and adults. People are most infectious 14 days before and seven days after the development of jaundice. Diagnosis of acute infection requires the use of serologic testing for immunoglobulin M anti–hepatitis A antibodies. The disease is usually self-limited, supportive care is often sufficient for treatment, and chronic infection or chronic liver disease does not occur. Routine hepatitis A immunization is recommended in children 12 to 23 months of age. Immunization is also recommended for individuals at high risk of contracting the infection, such as persons who use illegal drugs, those who travel to areas endemic for hepatitis A, incarcerated populations, and persons at high risk of complications from hepatitis A, such as those with chronic liver disease or HIV infection. The vaccine is usually recommended for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis, but immune globulin can be used in patients who are too young to be vaccinated or if the vaccine is contraindicated.

Hepatitis A is a common cause of acute hepatic inflammation and jaundice worldwide, and until 2004 it was the most commonly reported type of hepatitis in the United States.1 A combination of widespread vaccination, food safety practices, and improved sanitation decreased the incidence of hepatitis A in the United States from the 1970s until 2015. However, infection rates have recently increased because of large community outbreaks in susceptible individuals.2

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Serologic testing for immunoglobulin M anti–hepatitis A antibodies should be performed to confirm suspected hepatitis A.2,4 | C | Consensus-based national guidelines from ACIP and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Symptoms may be nonspecific | ||

| Hepatitis A vaccination should be offered to children 12 to 23 months of age and other populations at increased risk.2 | C | Consensus guidelines from ACIP |

| Confers lifelong immunity | ||

| Pre-exposure prophylaxis is indicated for unimmunized patients planning to travel to an area with increased incidence of hepatitis A (everywhere outside of the United States except for Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and western Europe).2 | C | Consensus guidelines from ACIP |

| Children younger than six months and persons with a contraindication to hepatitis A vaccine should receive immune globulin (Gamastan). | ||

| Persons older than 40 years and those with chronic liver disease should receive both hepatitis A vaccine and immune globulin. | ||

| All others should receive hepatitis A vaccine only. | ||

| Postexposure prophylaxis is recommended for all unvaccinated individuals who have had significant exposure to people with hepatitis A in the preceding two weeks.2 | C | Consensus guidelines from ACIP |

| Children younger than 12 months and people with a contraindication to hepatitis A vaccine should receive immune globulin. | ||

| Persons older than 40 years and those with chronic liver disease should receive both hepatitis A vaccine and immune globulin. | ||

| All others should receive hepatitis A vaccine only. |

Epidemiology

Worldwide, an estimated 1.4 million cases of hepatitis A are reported each year, and it remains a major infectious disease for most of the world's population.3 Before the development and implementation of the hepatitis A vaccine, annual cases of acute infection in the United States were reported in the tens of thousands, peaking at 59,606 cases in 1971.4 Following the licensing of the first vaccine, the annual number of U.S. cases fell by 92% between 1995 and 2010.1 This decline in cases occurred after only moderate vaccination coverage was achieved, indicating a substantial herd immunity effect.5 However, the United States has seen a steep increase in cases, driven by several person-to-person and food-related outbreaks beginning in 2016.4,6,7 These episodes, along with several outbreaks in Europe over the past five years, have led to resurgences of hepatitis A in areas considered low-endemic regions.3,8 The lack of widespread adult immunity in the affected nations, whether due to poor immunization rates or few previous infections, provides fuel for outbreaks.9 Advances in virus genotyping have allowed researchers to track outbreak origin and trajectory.10

Transmission and Risk Factors

Hepatitis A virus is a nonenveloped positive-strand RNA virus classified as a picornavirus, whose only natural host is humans.1 Remarkably stable in many environments and able to survive on surfaces for weeks, hepatitis A virus is transmitted through ingestion of infected stool particles.11–13 The virus is absorbed in the stomach and intestines, travels to the liver via the portal circulation, and replicates in hepatocytes.11,12 Detectable virus appears in blood and feces approximately 10 to 12 days after infection and may be excreted in stool for up to three weeks after the onset of symptoms.1,12 Viral shedding may begin weeks before symptom onset, contributing to the scope of outbreaks.4,12 Close interpersonal or sexual contact with an infected person and consumption of contaminated food or water are the most common routes of infection.4,14 Less commonly, infection has resulted from injection drug use or blood transfusion.4,12,14 Risk factors for contracting hepatitis A and characteristics that increase the risk of complications from infection are listed in Table 1.2

| People at higher risk of hepatitis A |

| Illegal drug users |

| International travelers to areas with high or intermediate rates of endemic infection (all areas outside of the United States except Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and western Europe) |

| Men who have sex with men |

| People who are homeless |

| People living in group settings for those with developmental disabilities |

| People who are incarcerated |

| People who have personal contact with an international adoptee from a country with high or intermediate rates of endemic infection |

| People with occupational risk for exposure (e.g., individuals working with hepatitis A virus in laboratories) |

| People at higher risk of severe disease from hepatitis A |

| People with chronic liver disease |

| Alcoholic liver disease |

| Autoimmune hepatitis |

| Cirrhosis (any type) |

| Fatty liver disease |

| Hepatitis B |

| Hepatitis C |

| Transaminase levels more than two times the upper limit of normal |

| People with HIV infection |

Presentation and Complications

An incubation phase of approximately 30 days (range = 15 to 50) is followed by the development of infectious symptoms in most adults and children six years and older.4,12 Approximately 70% of children younger than six years remain asymptomatic.4 Patients often initially experience nonspecific flulike symptoms of fever, malaise, nausea with vomiting, and abdominal pain that may progress to the classic findings of dark urine and jaundice in 70% of adults and older children.4,12 Although less common, diarrhea, joint pain, pruritus, and skin eruptions may also occur.12 Hepatomegaly and jaundice are the most common examination findings, occurring in 78% and 40% to 80% of patients, respectively.12

Patients with hepatitis A are most likely to spread the disease in the 14 days before jaundice develops, corresponding with the highest level of the virus in the stool.15 Infectivity decreases after jaundice is observed, and most individuals are considered to be noninfectious one week after the onset of jaundice.15

Most cases of acute hepatitis A are self-limited. Unlike other types of viral hepatitis, hepatitis A is not a chronic disease. However, approximately 10% to 15% of patients may take up to six months to fully recover or may have recurrent symptoms during this time frame.12 Occurring in less than 1% of patients, acute liver failure is more likely in patients who are older than 40 years at the time of infection and in those with underlying liver disease.12,16 Rare but serious extrahepatic manifestations have been reported, including acute renal failure, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, reactive arthritis, anemia, and pleural or pericardial effusion.12,16–18 Pregnant patients who develop hepatitis A are at increased risk of complications such as preterm contractions, placental separation, and premature rupture of membranes, increasing the likelihood of preterm labor and delivery.19

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of hepatitis A cannot be made solely on clinical grounds.1 Laboratory findings in symptomatic patients may include elevations of serum transaminase levels (with the alanine transaminase level higher than the aspartate transaminase level), total and direct bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase, which may take two to three months to resolve.12,15,17 In cases of severe symptoms, further testing may include a complete blood count, prothrombin time, serum electrolytes, and glucose level; a creatinine level greater than 2 mg per dL (176.8 μmol per L) is a positive predictor of fulminant hepatitis and death.12 No nonspecific laboratory findings are diagnostic of hepatitis A.2

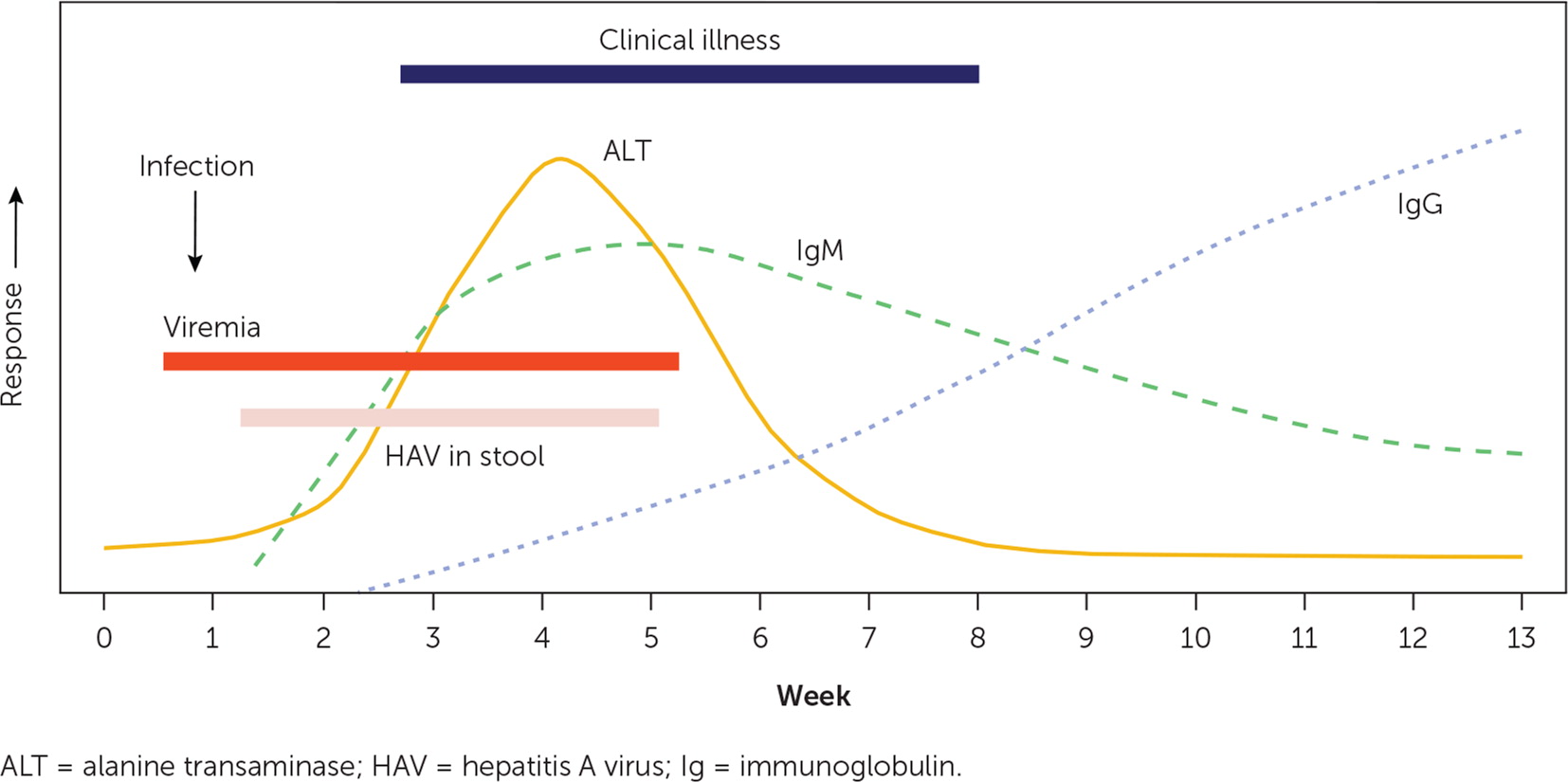

Similarly, although epidemiologic factors may suggest hepatitis A, serologic testing is required to confirm the diagnosis.2,4 Immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti–hepatitis A antibodies generally become detectable five to 10 days before the onset of symptoms, peak within one month of illness, and can persist for more than six months.15 Testing is recommended only for symptomatic patients with suspected hepatitis A. IgG anti–hepatitis A antibodies appear during the convalescent phase, remain elevated throughout a patient's lifetime, and indicate enduring protection against hepatitis A; unimmunized patients who are IgM anti–hepatitis A negative but IgG anti–hepatitis A positive are considered to have evidence of past infection and recovery.15 Total anti–hepatitis A contains measurements of both IgM and IgG, and it can be used to identify unimmunized patients who are immune because of previous hepatitis A.2 Molecular virology methods may be useful in the investigation of common-source outbreaks of hepatitis A but are not necessary for routine clinical diagnosis.2 The expected laboratory findings and clinical course of acute hepatitis A are represented in Figure 1.20

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for hepatitis A.2 Relative rest, oral rehydration, and treatment of symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are recommended. Hepatotoxins, including acetaminophen and alcohol, should be avoided. If fulminant hepatic failure develops, characterized by acute mental status changes or new coagulopathy, liver transplantation may be considered.

Prevention

Vaccination with inactivated hepatitis A antigen is the primary approach to preventing acute infection in the United States. There are two single-antigen vaccines (Havrix and Vaqta) and a combination vaccine (Twinrix) that contains Havrix and hepatitis B viral antigen (Table 2).21 Vaccine effectiveness is reported at 94% for Havrix (two doses) and 100% for Vaqta (one dose) four weeks after immunization.2 Long-term data following the completion of a two-dose series of both Havrix and Vaqta suggest lifelong immunity with this immunization schedule.2 Single-dose immunization is not recommended in the United States.2 Hepatitis A vaccines can be administered concurrently with other vaccines.2 Routine vaccination is recommended for children 12 to 23 months of age and for other high-risk populations2 (Table 12). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends vaccination for any pregnant patient with an indication for vaccination and for any patient who requests immunization.2 Vaccination is not routinely recommended for health care workers, sewer workers, plumbers, or child care workers.1

| Vaccine | Age | Dose | Number of doses | Schedule* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Havrix | 12 months to 18 years | 720 ELISA units per 0.5 mL | 2 | 0 and 6 to 12 months |

| 18 years and older | 1,440 ELISA units per mL | 2 | 0 and 6 to 12 months | |

| Vaqta | 12 months to 18 years | 25 U per 0.5 mL | 2 | 0 and 6 to 18 months |

| 18 years and older | 50 U per mL | 2 | 0 and 6 to 18 months | |

| Twinrix (hepatitis A and B) | 18 years and older, regular schedule† | 720 ELISA units/20 mcg per mL | 3 | 0, 1, and 6 months |

| 18 years and older, accelerated schedule† | 720 ELISA units/20 mcg per mL | 4 | Days 0, 7, and 21 to 30, with a booster at 12 months |

Administration of immune globulin (Gama-stan) provides passive immunization by introduction of anti–hepatitis A antibodies.2 Although it can be given simultaneously with inactivated vaccines administered at different sites, the manufacturer recommends that the measles-mumps-rubella and varicella virus vaccines be given two weeks before or six months after immune globulin.2 Potential adverse effects of immune globulin include hypersensitivity reactions and an increased risk of thrombosis,22 and it is more expensive than available vaccines.23,24 Unlike with the hepatitis A vaccine, the protection provided by immune globulin is limited to approximately three months.2

Pre-exposure prophylaxis is indicated for unimmunized patients who are planning to travel to an area with an increased incidence of hepatitis A, which is considered to be everywhere outside of the United States except for Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, and western Europe.2 In general, all otherwise healthy children younger than six months and persons with an allergy to the hepatitis A vaccine should receive immune globulin instead. Persons older than 40 years and those older than six months who are immunocompromised or have chronic liver disease should receive both the vaccine and immune globulin. All other individuals should receive hepatitis A vaccine only (Table 3).2

| Age | Health status | Hepatitis A vaccine | Immune globulin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger than 6 months | Healthy | NA | 0.1 to 0.2 mL per kg |

| 6 to 11 months | Healthy | 1 dose | NA |

| 12 months to 40 years | Healthy | 1 dose | NA |

| Older than 40 years | Healthy | 1 dose | 0.1 to 0.2 mL per kg |

| Older than 6 months | Chronic liver disease or Immunocompromised | 1 dose | 0.1 to 0.2 mL per kg |

| Older than 6 months | Patient declines vaccination or Vaccine contraindicated | NA | 0.1 to 0.2 mL per kg |

Postexposure prophylaxis is recommended for all unvaccinated individuals with significant exposure in the previous two weeks, including sex partners, household contacts, or known contaminated food sources.2 Immune globulin should be given only to children younger than 12 months and those in whom the vaccine is contraindicated, such as someone with an allergy to neomycin or another component of the vaccine.2 Both the vaccine and immune globulin are recommended for adults older than 40 years and children older than 12 months who are immunocompromised or have chronic liver disease. All other patients should receive a single dose of hepatitis A vaccine (Table 4).2 In the event of a community outbreak, public health officials should help to coordinate an effective postexposure prophylaxis strategy.

| Age group | Health status | Hepatitis A vaccine | Immune globulin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger than 12 months | Healthy | NA | 0.1 mL per kg |

| 12 months to 40 years | Healthy | 1 dose | NA |

| Older than 40 years | Healthy | 1 dose | 0.1 mL per kg |

| 12 months and older | Chronic liver disease or Immunocompromised | 1 dose | 0.1 mL per kg |

| 12 months and older | Vaccine contraindicated | NA | 0.1 mL per kg |

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Brundage and Fitzpatrick25 and Matheny and Kingery.21

Data Sources: We conducted literature searches using Ovid, PubMed, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force database, focusing on the keywords hepatitis A and hepatitis A immunization. Search dates: October 2020 through May 2021.