Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):376-385

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Bioterrorism is the deliberate release of viruses, bacteria, toxins, or fungi with the goal of causing panic, mass casualties, or severe economic disruption. From 1981 to 2018, there were 37 bioterrorist attacks worldwide. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists anthrax, botulism, plague, smallpox, tularemia, and viral hemorrhagic fevers as category A agents that are the greatest risk to national security. An emerging infectious disease (e.g., novel respiratory virus) may also be used as a biological agent. Clinicians may be the first to recognize a bioterrorism-related illness by noting an unusual presentation, location, timing, or severity of disease. Public health authorities should be notified when a biological agent is recognized or suspected. Treatment includes proper isolation and administration of antimicrobial or antitoxin agents in consultation with regional medical authorities and the CDC. Vaccinations for biological agents are not routinely administered except for smallpox, anthrax, and Ebola disease for people at high risk of exposure. The American Academy of Family Physicians, the CDC, and other organizations provide bioterrorism training and response resources for clinicians and communities. Clinicians should be aware of bioterrorism resources.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Tecovirimat (TPOXX) may be used for the treatment of smallpox in addition to post-exposure vaccination.33 | C | Consensus guideline |

| Botulism antitoxin heptavalent (A, B, C, D, E, F, G - equine) should not be delayed for the treatment of suspected botulism poisoning while awaiting formal confirmation.43 | C | Consensus guideline |

| Vaccination for smallpox, anthrax, and Ebola disease should be considered for people at high risk of exposure.22–25 | C | Consensus guidelines |

Although many pathogens may be used in a bioterrorist attack, the most concerning agents to national security and public health are anthrax, smallpox, plague, tularemia, botulism, and viral hemorrhagic fevers, in descending order of likelihood1 (Table 13). These pathogens are considered category A agents by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and are the focus of this article.

| Categories | Bacteria | Viruses | Toxins |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: most concerning to national security and public health because of ease of dispersal, transmission between people, high mortality rates, and the potential to cause panic; significant planning needed for public health preparedness | Anthrax: Bacillus anthracis Plague: Yersinia pestis Tularemia: Francisella tularensis | Smallpox: variola major Viral hemorrhagic fevers: Ebola, Lassa, Machupo, Marburg | Botulism: Clostridium botulinum |

| B: lower mortality rates compared with category A agents; relative ease of dissemination and moderate morbidity; requires special resources for surveillance and diagnostics | Brucellosis: Brucella species Salmonella* Escherichia coli O157:H7* Shigella* Glanders: Burkholderia mallei Melioidosis: Burkholderia pseudomallei Psittacosis: Chlamydia psittaci Q fever: Coxiella burnetii Typhus fever: Rickettsia prowazekii Vibrio cholerae† Cryptosporidium parvum† | Viral encephalitis: Eastern equine encephalitis Venezuelan equine encephalitis Western equine encephalitis | Epsilon: Clostridium perfringens Ricin toxin (castor beans) Staphylococcal enterotoxin B |

| C: includes any emerging pathogen that could be exploited | Any emerging pathogen | Any emerging pathogen | Any emerging pathogen |

Although bioterrorism is currently considered a low-probability event, many pathogens that could be used in bioterrorist attacks occur naturally. Five of the category A agents—anthrax, botulism, plague, Ebola virus, and Lassa fever—were noted to occur naturally in endemic regions in 2020.4 There is also concern that these (or other) pathogens could be altered to increase virulence or cause resistance to current medications and vaccines.5 Laboratory accidents have resulted in the release of harmful pathogens, and the shipment of viable agents and unaccounted stocks of these agents highlight the risk of poor biosecurity.2,6,7 An emerging infectious disease, such as a novel respiratory virus, might also be exploited, bypassing the expertise needed to obtain and weaponize other well-known agents.

In 2001, powdered anthrax spores were mailed through the United States Postal Service to several government employees and news media outlets. This attack resulted in 11 cutaneous and 11 inhalational cases of anthrax, with five of the inhalational cases being fatal.1,10 An estimated $320 million was needed for decontamination, and 10,000 people were recommended for postexposure prophylaxis.11,12 In 2020, ricin (a poison found in castor beans) was mailed to the President of the United States and five residents of Texas.13 Ricin can cause death within 36 to 72 hours, and there is no known antidote.14

The initial diagnosis of illness caused by biological agents could be delayed because of a lack of clinical experience with or knowledge about these agents.15 The goal of this article is to provide primary care physicians with basic information about category A agents, supporting them in detecting and responding to a bioterrorist attack, which may include assisting in a mass casualty event.15,16 Primary care physicians may be the first to recognize a bioterrorism-related illness by noting an unusual presentation, location, timing, or severity of disease.

Anthrax

Anthrax is a naturally occurring zoonotic disease with worldwide distribution caused by the spore-forming, gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium, Bacillus anthracis.17 Although anthrax is a disease primarily affecting wild and domestic herbivores, it occasionally causes human illness and is potentially fatal.

The human disease has a variety of manifestations. Cutaneous disease is most common, but anthrax that is inhaled possesses a higher degree of lethality.18 The inhalational form is of concern to bioterrorism because it is easily disseminated and can cause widespread illness and death.2,19 For instance, an aerosolized release of anthrax into the Washington, DC area could result in 1 million to 3 million deaths.16

The median incubation period for anthrax in the 2001 attack was four days, but incubation may extend for up to two months postexposure.19 The initial presentation of inhalational anthrax is difficult to distinguish from other common illnesses such as community-acquired pneumonia, seasonal influenza, or COVID-19. Symptoms are constitutional and include fevers, chills, lethargy, and cough.

The mortality rate of naturally occurring inhalational anthrax is 30% to 45%, and refined spores, which would likely be used in a malicious attack, would be even more lethal.17,19 Anthrax disease can be confirmed with laboratory diagnostic testing such as a Gram stain or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The historical test of choice is a bacterial culture.

MANAGEMENT

| Disease | Inpatient treatment | Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Anthrax | Ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV twice daily or Doxycycline, 200 mg IV, then 100 mg IV twice daily plus 1 to 2 additional antibiotics known to be effective against anthrax All regimens should be combined with U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved monoclonal antibody (raxibacumab [Abthrax] or obiltoxaximab [Anthim]) or anthrax immune globulin intravenous (Anthrasil) | Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg orally twice daily for 60 days; if unvaccinated, begin initial doses of vaccine (total of 3 doses is preferred) or Doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily for 60 days, plus vaccination (total of 3 doses is preferred) |

| Smallpox | Tecovirimat (TPOXX), 600 mg orally twice daily for 14 days | Vaccinia immune globulin, 100 mg per kg, administered IM within 7 days plus Immediate vaccination or revaccination (most effective if done within the first 4 days) |

| Plague | Streptomycin, 1 g IM twice daily for 10 to 14 days or Gentamicin, 5 mg per kg IM or IV once daily for 10 to 14 days or Ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV twice daily until clinically improved, then 750 mg orally twice daily for a total of 10 to 14 days or Doxycycline, 200 mg IV, then 100 mg IV twice daily until clinically improved, then 100 mg orally twice daily for a total of 10 to 14 days | Doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days or duration of exposure or Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days |

| Tularemia | Streptomycin, 1 g twice daily for 10 to 14 days or Gentamicin, 5 mg per kg per day IV or IM for 10 to 14 days or Doxycycline, 100 mg IV twice daily or Ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV twice daily | Doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days or Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg orally twice daily for 14 days |

| Botulism | Multiple botulism antitoxins are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Most widely used agent is botulism antitoxin heptavalent (A, B, C, D, E, F, G - equine) | None available |

| Viral hemorrhagic fevers | Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) and ansuvimab (Ebanga) for Ebola virus Ribavirin (Virazole for Lassa virus, Arenaviridae, Bunyaviridae, and other viral hemorrhagic fevers, 30 mg per kg IV (maximum: 2 g), then 16 mg per kg (maximum: 1 g per dose) IV every 6 hours for 4 days, then 8 mg per kg (maximum: 500 mg per dose) IV every 8 hours for 6 days | None available |

| Agent | Route of administration | Schedule | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthrax pre-exposure22 | Intramuscular (0.5 mL) | 0, 1, and 6 months (primary series) Booster at 12 months and 18 months Then 12-month intervals If the above regimen is completed: booster may be given every 3 years (instead of annually) to people not at high risk of exposure who want to maintain protection | High-risk groups: Military members on deployment to specific regions as outlined by the U.S. Department of Defense Laboratory personnel involved with Bacillus anthracis Farmers, veterinarians, or other workers who may handle infected animals Pregnant patients should not be vaccinated for anthrax unless benefits outweigh risks |

| Anthrax postexposure22 | Subcutaneous (0.5 mL) | 0, 2, and 4 weeks postexposure Augment with appropriate antibiotic therapy | Must have suspected or known exposure to B. anthracis 18 to 65 years of age Emergency authorization for children, pregnant patients, and older patients If vaccine cycle is interrupted, do not restart; administer the next dose and finish the series |

| Smallpox vaccine (Vaccinia)23 | Percutaneous | Revaccination schedule: At least every 10 years if exposed to vaccinia viruses Every 3 years if potential for exposure to variola virus or monkeypox | Severe adverse effects: progressive vaccinia, postvaccine encephalitis, eczema vaccinatum, myopericarditis Contraindications: significant cardiovascular disease, pregnant or breastfeeding, HIV infection, immunosuppression, history of eczema or other significant skin disorder, or close contact with any of the above. If exposed to smallpox then there are no absolute contraindications |

| Live, non-replicating smallpox vaccine (Jynneos)24 | Subcutaneous (0.5 mL) | 0 and 4 weeks | Approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2019 for people at risk of smallpox and monkeypox 18 years and older Attenuated nonreplicating vaccinia virus No severe adverse effects |

| Live, Ebola Zaire vaccine25 | Intramuscular (1 mL) | Single-dose pre-exposure prophylaxis Single-dose postexposure prophylaxis ideally administered immediately after exposure | Prevention of Ebola Zaire only 18 years and older Duration of immunity is unknown Effectiveness is not known when combined with antivirals or immunoglobulins Pregnancy consideration: neonatal outcomes are poor when mothers are infected with Ebola virus; the decision to vaccinate should be based on risks vs. benefits and potential exposure to Ebola Zaire People who are vaccinated should continue to follow infection control precautions |

Treatment for active illness involves antimicrobial therapy with the administration of anthrax antitoxins or monoclonal antibodies.26 There are currently two monoclonal antibodies and one antitoxin approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): raxibacumab (Abthrax), obiltoxaximab (Anthim), and anthrax immune globulin intravenous (Anthrasil).26 These agents should be administered in consultation with regional medical authorities and the CDC.

Smallpox

Smallpox infection has two forms: the more lethal variola major and the milder variola minor. Transmission is primarily via the respiratory tract, and person-to-person transmission is the most common. Smallpox is one of the highest-threat biological agents because it is highly contagious, and only 100 infected individuals could cause a pandemic.15 The historical fatality rate of smallpox is between 30% and 50% in an unvaccinated population.28 Current modeling of aerosolized smallpox suggests a higher fatality rate if it were released today.27,29 Routine vaccination against smallpox in the United States ended in 1972, and people who were vaccinated before that date have unknown immunity.30

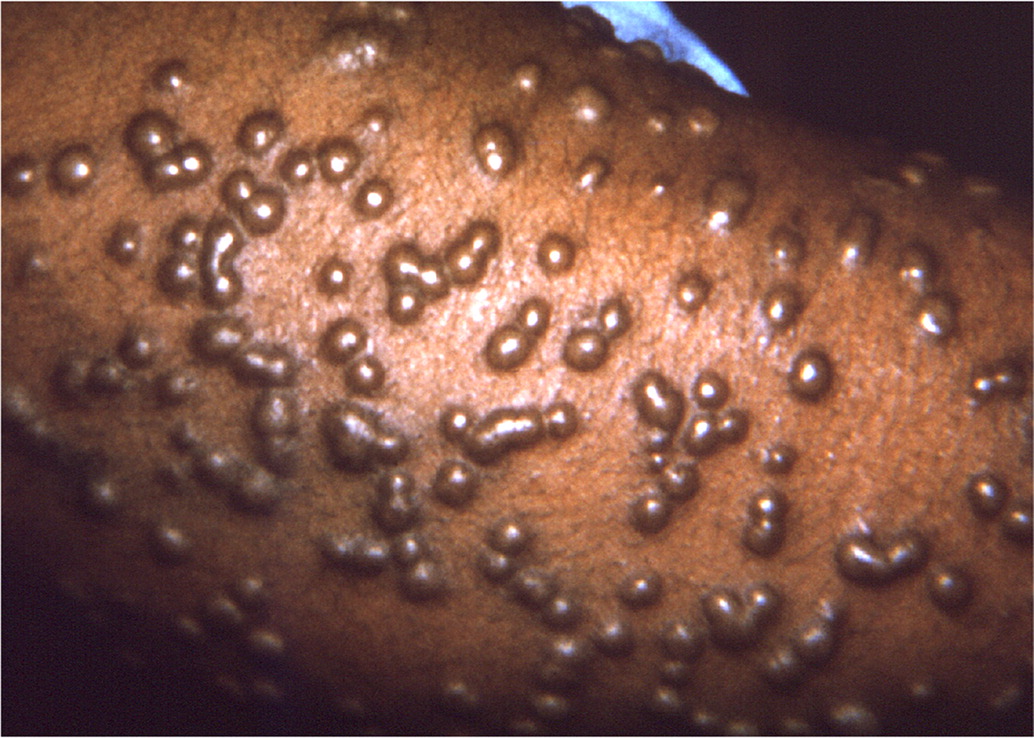

Following a 12- to 14-day incubation period, smallpox presents with high fevers, vomiting, headaches, myalgias, and malaise. This initial phase is closely followed by a characteristic rash on the face, forearms, and mucous membranes of the oropharynx. The rash is initially maculopapular, but the pathognomonic rash has deep-seated, rigid vesicles in the same stage of development (Figure 131). Involvement of the palms and soles is also typical. Infection must be confirmed in a CDC-certified laboratory using approved PCR testing protocols.

MANAGEMENT

Vaccine prophylaxis is an option to prevent or reduce severity, but it is only applicable if administered before symptom onset, ideally within four days of exposure.32 Fetal vaccinia has been reported after smallpox vaccination of pregnant patients; therefore, the vaccine should not be administered during pregnancy unless benefits are thought to outweigh risks.

In 2018, the FDA approved tecovirimat (TPOXX) for the treatment of smallpox.33 Although limited clinical data are available, tecovirimat, which interrupts virus transmission between cells, has been used to treat severe vaccinia.34 The antiviral agents cidofovir and brincidofovir have also shown effectiveness against other orthopoxviruses. Pregnant patients should receive similar treatment after exposure. Reluctance to treat may lead to adverse outcomes.

Plague

Plague is caused by the gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis.35 The most common form is bubonic plague, which occurs after the bite of an infected flea. Clinical features include fever and painfully swollen lymph nodes called buboes.

Pneumonic plague is less common but highly contagious because it is spread from person to person. The pneumonic plague has a case-fatality rate approaching 100% in the absence of effective treatment. A productive cough with bloody sputum defines the pneumonic form.15 The pneumonic plague is the greatest threat as an agent of bioterrorism, with an aerosolized release resulting in many primary pneumonic plague cases.15

The incubation period is typically one to six days. The bacterium can be isolated directly from bubo aspirates and cultured from sputum, tracheal aspirates, or blood. Additional diagnostic techniques include PCR testing and culture methodologies because the bacterium grows well on standard media.

MANAGEMENT

Tularemia

Tularemia is a zoonotic disease caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. This pathogen has a geographic distribution throughout North America.37 It has many natural reservoirs, with domestic rabbits serving as the primary source of human infection through direct contact.

Tularemia can present in many forms, from asymptomatic to symptoms of severe disease and death; however, the pneumonic form is the biggest threat as a biological weapon because an aerosolized dispersal could result in a large number of pleuropneumonia cases.37 Diagnosis is confirmed with fluorescent antibody testing, immunohistochemical staining, or PCR testing of tracheal or blood samples.

MANAGEMENT

| Mechanism of dissemination | Agents | Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Airborne | Smallpox Any severe emerging infection that is transmitted by small particles where there is no specific treatment or vaccine | Hand hygiene Gown Gloves Eye protection N95 mask or higher Negative pressure private room, or grouped with others who have the same illness |

| Droplet | Viral hemorrhagic fevers Pneumonic plague Influenza | Hand hygiene Gown Gloves Eye protection Surgical mask Private room or grouped with others who have the same illness |

| Contact | Toxins Nonpneumonic plague Tularemia Anthrax Category B agents | Hand hygiene Gown Gloves Eye protection Surgical mask if concern for splashes |

Botulism

Botulism is caused by the toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum, a spore-forming bacterium that occurs naturally in soil. The toxin has potent neuroparalytic effects.39 By mass, the botulinum neurotoxin is the most poisonous substance known.

Botulism is characterized by neuroparalytic signs, typically starting with cranial nerve involvement that presents as diplopia, dysphagia, and dysarthria in an afebrile patient. A progressive, bilateral, descending motor neuron flaccid paralysis then follows, resulting in respiratory failure and death.40

Most natural illnesses related to botulinum toxin occur because of improper food storage (canning or pickling) or as the result of under-cooked food.41 The most likely bioterrorism scenarios include intentional contamination of foodstuffs or aerosolization of the bacterium. Laboratory confirmation is achieved by finding botulinum toxin in stool or blood or by culturing C. botulinum directly.

MANAGEMENT

The most widely used agent is botulism antitoxin heptavalent (A, B, C, D, E, F, G - equine). Administration of antitoxins does not reverse paralysis but halts further progression42; therefore, early administration is crucial.43 Obtaining the antitoxin for infants and adults requires consultation with your state health department and subsequent consultation with and distribution of the antitoxin from the CDC. Initiation of the process should not be delayed while awaiting formal confirmation of disease.44,45

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fevers of importance to humans are caused by viruses that are members of the Filoviridae and Arenaviridae families.46 Category A agents include the geographically dispersed Lassa, Ebola, and Marburg viruses, and the Machupo virus that is endemic in South America. Bats and rodents are typically the suspected reservoirs for Filoviridae and Arenaviridae, respectively.

Naturally occurring viral hemorrhagic fevers are contracted through direct contact with bodily fluids. In a bioterrorist attack, aerosolization is the most likely mode for dissemination.47

Incubation ranges from two to 21 days, followed by abrupt onset of fevers, myalgia, headaches, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.48 Late-stage manifestations include hepatic failure, renal failure, hemorrhagic diathesis, shock, and multiorgan dysfunction.

Diagnosis focuses on antigen detection assays or PCR testing of blood samples. Direct virus isolation is also an option.

MANAGEMENT

Isolation of patients suspected of having a viral hemorrhagic fever is essential, and treatment has focused on supportive measures. In recent years, progress has been made in the treatment of Ebola disease. Several new FDA-approved treatments exist (Table 220). Monoclonal antibody treatments are under evaluation, notably atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) and ansuvimab (Ebanga). Both therapies have demonstrated benefit when administered to patients with Ebola hemorrhagic fever.49

Preparing for a Bioterrorist Attack

TRAINING AND INFECTION CONTROL

Mass casualty and disaster management are not routinely included in medical school or residency curricula.50,51 A national survey of 1,603 physicians found that only one-third of respondents reported feeling comfortable about their ability to manage public health emergencies such as bioterrorist attacks, and only one-half had participated in emergency training during the previous two years.52

Training resources are available (Table 5). The American Academy of Family Physicians provides resources for personal, practice, and community preparedness. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has a comprehensive list of training resources on bioterrorism and disaster preparedness. The U.S. Army offers didactics on the medical management of biological weapon casualties and free downloadable guides on bioterrorism.20,53 There are also volunteer and training opportunities for clinicians interested in disaster management.54,55

| Updated Disaster Preparedness Resources, American Academy of Family Physicians https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180911disasterprep.html |

| HealthMap, Boston Children's Hospital https://healthmap.org/en/ |

| Preparation and Planning for Bioterrorism Emergencies, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://emergency.cdc.gov/bioterrorism/prep.asp |

| Training Resources, U.S. Department of Homeland Security https://www.dhs.gov/science-and-technology/frg-training |

| Training, Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health Preparedness https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-public-health-preparedness/training/index.html |

| Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases, International Society for Infectious Diseases https://promedmail.org/ |

| Reference Materials, United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases https://www.usamriid.army.mil/education/instruct.htm |

| Biological Weapons, World Health Organization https://www.who.int/health-topics/biological-weapons#tab=tab_1 |

In the event of a bioterrorism incident, infection control and contact tracing will be important to mitigate an outbreak effectively and will likely focus on isolating affected individuals.56 The availability of personal protective equipment will need to be maximized. Established routes of communication with local public health departments will be important for establishing and refining disaster protocols.

Clinicians should be familiar with the treatment of children and pregnant patients because a bioterrorist attack would likely affect broad segments of the population.57

VACCINATIONS

Routine vaccinations should be maintained as outlined by the CDC.55 However, immunizations for potential biological agents are not regularly administered, except to high-risk groups such as military personnel and laboratory workers (Table 322–25). Vaccination for smallpox, anthrax, and Ebola disease should be considered for people at high risk of exposure.23 There are two smallpox vaccines: ACAM2000 and Jynneos.23,24 An anthrax vaccine (BioThrax) is approved for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis.22 The Ervebo vaccine for Ebola Zaire was approved in 2019 for people 18 years and older.25 Vaccination for tularemia, plague, and botulism is not available in the United States.

SURVEILLANCE

Microorganisms can be transported globally in a short amount of time. Examples included Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in 2003, Ebola disease in 2014, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in 2015, and SARS-CoV-2 in 2019. It may be difficult to distinguish emerging infections from a bioterrorism event. An infectious agent that is genetically manipulated or not endemic may suggest a bioterrorism event.58 When a bioterrorist attack is suspected, it is crucial to notify public health officials to allow for the mobilization of resources (Table 6).

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emergency Operations Center 770-488-7100 |

| Environmental Protection Agency National Response Center 800-424-8802 |

| Federal Emergency Management Agency Center for Domestic Preparedness 866-213-9553 |

This article updates a previous article on this topic by O'Brien, et al.1

Data Sources: PubMed was searched using the key words evaluation, treatment, preparedness, surveillance, detection of bioterrorism, anthrax, plague, smallpox, tularemia, botulism, and viral hemorrhagic fevers. An Essential Evidence Plus summary on bioterrorism was reviewed. The search was limited to English-only studies published since 2008. References from articles identified by the search were used. Search dates: October 2020 and April 2021.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army Medical Department or the U.S. Army Service at large.