Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(2):137-143

Patient information: See related handout on fever of unknown origin in adults, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Fever of unknown origin is defined as a clinically documented temperature of 101°F or higher on several occasions, coupled with an unrevealing diagnostic workup. The differential diagnosis is broad but is typically categorized as infection, malignancy, noninfectious inflammatory disease, or miscellaneous. Most cases in adults occur because of uncommon presentations of common diseases, and up to 75% of cases will resolve spontaneously without reaching a definitive diagnosis. In the absence of localizing signs and symptoms, the workup should begin with a comprehensive history and physical examination to help narrow potential etiologies. Initial testing should include an evaluation for infectious etiologies, malignancies, inflammatory diseases, and miscellaneous causes such as venous thromboembolism and thyroiditis. If erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein levels are elevated and a diagnosis has not been made after initial evaluation, 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan, with computed tomography, may be useful in reaching a diagnosis. If noninvasive diagnostic tests are unrevealing, then the invasive test of choice is a tissue biopsy because of the relatively high diagnostic yield. Depending on clinical indications, this may include liver, lymph node, temporal artery, skin, skin-muscle, or bone marrow biopsy. Empiric antimicrobial therapy has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of fever of unknown origin and therefore should be avoided except in patients who are neutropenic, immunocompromised, or critically ill.

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) in adults poses one of the greatest diagnostic challenges in medicine. For a large proportion of patients presenting with FUO in higher-income countries, a cause is never identified, and many cases are due to atypical presentations of common illnesses rather than rare disorders.1,2 The lack of a standard diagnostic workup leads to frustration for physicians and patients, and numerous noninvasive and invasive procedures are often performed without arriving at a definitive diagnosis.1,3 Currently, the most widely accepted definition of FUO requires only a clinically documented temperature of 101°F (38.3°C) or higher on several occasions and an unrevealing diagnostic workup.2,4 Previous definitions have provided suggested minimal time frames for investigation; however, these were acknowledged to be arbitrary and are not included in the current consensus definition.2,4

Differential Diagnosis

Common causes of FUO include infections, malignancies, noninfectious inflammatory disease (e.g., vasculitides, granulomatous disease, connective tissue diseases), miscellaneous, and undiagnosed2,4,5 (Table 16). Lower-income countries typically have higher rates of infection and malignancy as causes of FUO. Noninfectious inflammatory diseases and undiagnosed cases typically predominate in higher-income countries, most likely because of access to advanced imaging that can enable tumor detection.1,2,5

| Subgroup | Causes |

|---|---|

| Infection (20% to 40%) | Bacterial |

| Abdominal or pelvic abscesses | |

| Dental abscesses | |

| Endocarditis | |

| Sinusitis | |

| Tuberculosis (especially extrapulmonary/disseminated) | |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Viral | |

| Cytomegalovirus | |

| Epstein-Barr virus | |

| Malignancy (20% to 30%) | Colorectal cancer |

| Leukemia | |

| Lymphoma (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin) | |

| Noninfectious inflammatory disease (10% to 30%) | Connective tissue diseases |

| Adult Still disease | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Granulomatous disease | |

| Crohn disease | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Vasculitis syndromes | |

| Giant cell arteritis | |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | |

| Temporal arteritis | |

| Miscellaneous (10% to 20%) | Drug induced |

| Factitious fever | |

| Thromboembolic disease | |

| Thyroiditis |

Evaluation

INITIAL EVALUATION

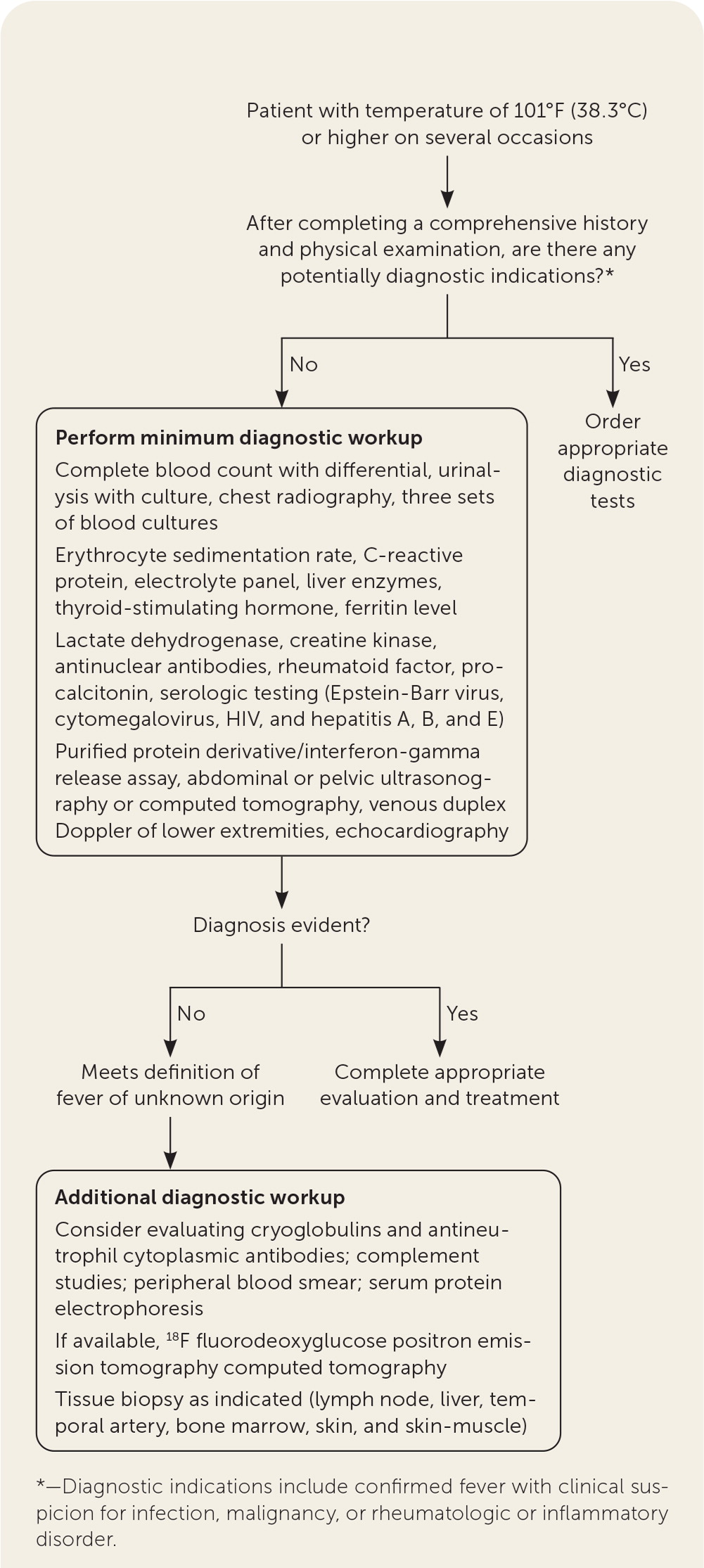

Early identification and precise localization of the cause are key because diagnostic delay worsens outcomes and contributes to deaths2; however, there are no evidence-based guidelines for the evaluation of FUO. As a result, recommended approaches are largely based on expert opinion. Figure 1 outlines a suggested approach to the evaluation of FUO, beginning with a comprehensive history and physical examination.6 The initial history should include a complete accounting of the patient's symptoms and history of travel; work history; housing and home environment; recent medication use; tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drug use; contact with animals or sick people; and family history of cancers and inflammatory disorders.7,8 At a minimum, physical examination should include evaluation of the skin, oropharynx (with particular attention to dentition), heart, abdomen, lymph nodes, and genitalia.8,9

It is important to rule out factitious fever, which has been reported in up to 9% of cases.10 It should be suspected in cases of fever lasting longer than six months and in medical personnel. Signs such as high temperatures without tachycardia or skin warmth or unusual fever patterns (e.g., brief spikes, loss of evening peak, absence of fever when an observer is present) should also bring the diagnosis of factitious fever to mind.1,2,8,10 It is important to confirm the presence of fever and any temporal pattern it may exhibit. Several infectious etiologies, including malaria and tuberculosis, follow classic fever patterns.8,10 Table 2 summarizes physical examination findings that may help in narrowing the potential etiology of the FUO.8 If one or more of these signs are present, associated conditions should be ruled out before initiating a more general evaluation. Although these signs are found in as many as 97% of patients, they lead to a diagnosis in only 62% of patients with FUO.4,11,12

| Finding | Potential etiology |

|---|---|

| Asymmetric pulse and/or blood pressure between extremities | Takayasu arteritis |

| Epididymal nodule | Extrapulmonary tuberculosis |

| Periarteritis nodosa | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Fever peaks in the morning | Polyarteritis nodosa |

| Typhoid fever | |

| Whipple disease | |

| Fever with bradycardia (facet sign) | Central nervous system malignancy |

| Lymphoma | |

| Typhoid fever | |

| Yellow fever | |

| Isolated hepatomegaly | Hepatic neoplasia |

| Metastatic carcinoma | |

| Q fever | |

| Renal neoplasia | |

| Lymphadenopathy | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| New heart murmur | Atrial myxoma |

| Infective endocarditis | |

| Oral ulcers | Behçet disease |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Rash | Sarcoidosis |

| Still disease | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Roth spots | Infective endocarditis |

| Spinal tenderness | Vertebral osteomyelitis |

| Splenomegaly | Cirrhosis |

| Crohn disease | |

| Cytomegalovirus | |

| Epstein-Barr virus | |

| Miliary tuberculosis | |

| Twice daily fever peak | Malaria |

| Miliary tuberculosis | |

| Still disease | |

| Visceral leishmaniasis |

Evaluation for Common Infections. Infectious etiologies account for a predominant number of early diagnoses in the evaluation of FUO.13 As a result, initial testing should include a complete blood count with differential, urinalysis with culture, three sets of blood cultures (a set comprises a pair of aerobic and anaerobic bottles, with each bottle containing 10 mL of blood) drawn from three different sites at the same time, and chest radiography. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein are useful acute-phase reactants because of their high sensitivity for infection and inflammation and a high negative predictive value for inflammatory causes.1,14,15 An elevated procalcitonin level of 0.5 ng per dL or more is associated with severe bacterial infections.16

Evaluation for specific infections includes serologic testing for Epstein-Barr virus; cytomegalovirus; hepatitis A, B, and E; and HIV, as well as tuberculosis skin testing (purified protein derivative), whole-blood interferon-gamma release assay, or acid-fast bacillus cultures and stains.17 Negative tuberculosis skin testing and whole-blood interferon-gamma release assay do not rule out active pulmonary tuberculosis, so chest radiography should be obtained to exclude pneumonia and pulmonary tuberculosis.

Echocardiography is useful when evaluating for infective endocarditis. Importantly, rates of infective endocarditis are rising in younger patients in part because of injection drug use.18 Ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis can assist in identifying abscesses.17 Ultrasonography is often the first-line recommendation because it has a lower cost and radiation exposure is avoided; however, CT has a high sensitivity (92% for abdominal CT) and specificity (60% to 70%) in determining the etiology of FUO.11

Evaluation for Malignancies. A markedly elevated lactate dehydrogenase may point to lymphoma or leukemia as the etiology.11,19 Elevated ferritin, although not specific, can be seen in myeloproliferative disorders.19 CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is recommended to evaluate for malignancy in patients with possible FUO.17

Evaluation for Inflammatory Diseases. In a prospective study, the three most common inflammatory conditions in FUO were Still disease, large vessel vasculitis, and polymyalgia rheumatica.20 An elevated white blood cell count, elevated ESR, and extremely elevated ferritin level (greater than 1,000 ng per mL [1,000 mg per L]) are consistent with adult Still disease.21 Elevated ESR and ferritin and creatine kinase levels warrant further evaluation for temporal arteritis; conversely, a normal ESR conveys a high negative predictive value for the same.14,15 In addition to characteristic features, ESR and C-reactive protein can be useful in evaluating for polymyalgia rheumatica.22

Elevated ESR, C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor, and/or antinuclear antibody indicate rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus as the etiology of the FUO. Patients with sarcoidosis may demonstrate characteristic findings on chest radiography or CT, including interstitial lung disease and hilar adenopathy.23 Likewise, abdominal CT findings of mural wall thickening may point toward Crohn disease.24

Evaluation for Miscellaneous Causes. Venous duplex imaging of the lower extremities can rule out venous thromboembolism, which in one study represented the etiology of FUO in 6% of patients.25 An elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone level should raise suspicion of thyroiditis as the etiology of the FUO; thyroid-stimulating hormone may also be suppressed in thyroiditis.17 Additionally, an electrolyte panel and liver enzymes can help identify other etiologies.

SECONDARY EVALUATION

Laboratory Studies. Inflammatory bowel disease should be considered as an etiology of FUO if initial evaluation does not demonstrate an etiology. Stool lactoferrin and calprotectin are both sensitive and specific for identifying intestinal inflammation from inflammatory bowel disease.26

Imaging Studies. Additional imaging is warranted if chest radiography and CT of the abdomen and pelvis are unrevealing.5 Nuclear imaging studies are generally sensitive, but not specific, in the evaluation of fever, except for technetium-based scans, which are insensitive but highly specific (93% to 94%).1,5 These studies are associated with lower radiation exposure than conventional radiography or CT, and technetium-based scans can be useful in localizing potential infectious or inflammatory foci.1,5 Targeted magnetic resonance imaging is useful in the evaluation of suspected focal etiologies such as epidural abscess but may be less accurate in the early stages of inflammatory and infectious diseases.5,27 Data from small retrospective studies indicate that whole-body magnetic resonance imaging can be helpful in detecting inflammatory foci in a large number of patients, but further prospective studies are needed.28 Highly sensitive for diagnosing infective, inflammatory, and neo-plastic processes, 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography CT (18F-FDG-PET/CT) scans allow for whole-body screening.3,20,25,29 Promising initial evidence shows that 18F-FDG-PET/CT scans may be cost-effective if employed earlier in the diagnostic course by virtue of eliminating numerous expensive and invasive investigations as well as reducing duration of hospitalization.29

Biopsies. Biopsies are useful in the setting of symptoms pointing toward a specific diagnosis. Bone marrow biopsy is a high-yield test, especially in the setting of clinical and laboratory parameters consistent with hematologic disease.30–33 One study found that early bone marrow biopsy showed abnormalities of bone marrow in 96.2% of patients with FUO and provided a specific diagnosis in 23.7%.30 Bone marrow biopsy has also been used as a rapid diagnostic tool in patients with comorbid HIV/AIDS and FUO.30,34 However, bone marrow cultures have extremely low diagnostic yield in immunocompetent patients and are not recommended for this population.1,30

Temporal artery biopsy remains useful in patients older than 55 years as a low-risk investigation to exclude giant cell arteritis as a cause of FUO, although the 18F-FDG-PET/CT scan is gaining popularity as a quick, accurate, and noninvasive diagnostic method.1,31,33,35 Liver biopsy has an ongoing role in the evaluation of FUO because it has a low risk of harm and provides a diagnostic yield of 14% to 27%, which is unchanged despite advances in noninvasive imaging.1,33,36 Lymph node biopsy is useful in cases of generalized lymphadenopathy, but it is not helpful if adenopathy was confined to cervical or inguinal regions.33 Skin and skin-muscle biopsy have had fair diagnostic yields when performed in suspect areas.34 Exploratory laparotomy and laparoscopy are no longer preferred because the accuracy of noninvasive diagnostic imaging has increased, but small studies have shown that exploratory laparoscopy may be a relatively safe and accurate last step in the evaluation of FUO.1,37

Empiric Treatment and Referral

Empiric antimicrobial therapy has not been shown to be effective in the treatment of FUO. Additionally, such treatment may delay the evaluation for the actual cause of the fevers.38 Therefore, empiric therapy should be avoided except in neutropenic, immunocompromised, and/or critically ill patients.39 Neutropenic patients who are febrile should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics and potentially antifungals secondary to the high incidence of serious bacterial and invasive fungal infections in this population.40

Up to 75% of patients with FUO will have spontaneous resolution of their fevers.1,11,12,38 If after at least an initial workup, no diagnosis is determined and the fever persists, infectious disease, rheumatology, or hematology/oncology consultation may be appropriate. The exact timing of consultation should be based on the patient's clinical condition and evaluation findings.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Hersch and Oh6 and by Roth and Basello.41

Data Sources: A literature search was conducted with PubMed search terms that included fever of unknown origin, prolonged fever, and adults. An Essential Evidence Plus search included relevant POEMs, Cochrane reviews, clinical decision rules, and a targeted PubMed search. Search dates: March 29 to April 28, 2021; July 23, 2021; and September 22, 2021.