Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(3):250-261

Patient information: See related handout on what parents should know about heart murmurs in children, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Up to 8.6% of infants and 80% of children have a heart murmur during their early years of life. The presence of a murmur can indicate conditions ranging from no discernable pathology to acquired or congenital heart disease. In infants with a murmur, physicians should review the obstetric and family histories to detect the possibility of congenital heart pathologies. Evaluation by a pediatric cardiologist is indicated for newborns with a murmur because studies show that neonatal murmurs have higher rates of pathology than in older children, and neonatal murmur characteristics are more difficult to evaluate during examination; referral is preferred over echocardiography. All infants, with or without a murmur, should have pulse oximetry screening to detect underlying critical congenital heart disease. In older children, most murmurs are innocent and can be followed with serial examinations if there are no findings of concern. Findings in older children that warrant referral include diastolic murmurs, loud or harsh-sounding murmurs, holosystolic murmurs, murmurs that radiate to the back or neck, or signs or symptoms of cardiac disease. Referral to a pediatric cardiologist is indicated when a pathologic murmur is suspected. Electrocardiography, chest radiography, and other tests should not be reflexively performed as part of all murmur evaluations because these tests can misclassify a murmur as innocent or pathologic, and they are not cost-effective. Emerging technologies include phonocardiography interpretation of murmurs and artificial intelligence algorithms for differentiating innocent from pathologic murmurs.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not repeat echocardiography in patients who are stable and asymptomatic with a murmur or click, where a previous examination revealed no significant pathology. | American Society of Echocardiography |

Despite the high prevalence of murmurs and the frequency with which physicians encounter them, evidence shows that physicians’ cardiac auscultation skills are suboptimal.7–9 In one study, physician examination had a 79.7% sensitivity and 88.5% specificity for discerning pathologic from innocent murmurs (positive predictive value = 87%; negative predictive value = 81.8%).10 However, there is variation based on specialty and training level.11,12

Heart Murmur Physiology and Terms

Murmurs result from perturbations in blood flow from pressure gradients or velocity changes that cause turbulent blood flow and vibration.13–16 The vibration is transmitted through the pericardium and chest wall and into the stethoscope. When the vibratory component is strong enough, a tactile vibration on the chest wall is noticeable as a cardiac thrill.

Innocent murmurs are commonly referred to as flow murmurs, physiologic murmurs, or functional murmurs. In contrast, pathologic murmurs are associated with congenital or acquired structural heart disease and often require medical or procedural interventions.

Incidence

Between 0.6% and 8.6% of infants who are asymptomatic with no apparent signs of a congenital syndrome have a heart murmur. Most of these murmurs are innocent; however, 37% of murmurs in infants with no apparent signs of congenital syndromes are diagnosed with congenital heart disease, and 2.5% of infants with a murmur have a critical lesion requiring procedural interventions early in life.19

Beyond infancy, innocent murmurs are more common, occurring in 20% to 80% of children.6,20 Innocent murmurs should disappear as the child transitions into adulthood.21 Pathologic murmurs beyond infancy are uncommon, with only 1% of childhood murmurs associated with structural heart disease that require intervention.2

History

INFANTS

The first step in evaluating an infant with a heart murmur is to review the obstetric and family histories. Although most congenital heart disease is not caused by a known genetic abnormality, the probability of congenital heart disease is higher in children who have siblings or other family members with congenital heart disease.22 Table 1 lists factors to consider when taking a history for an infant with a heart murmur.14,22–27

| Personal history | |

| History of acute rheumatic fever, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or Kawasaki disease | |

| Family history | |

| Congenital heart disease | Depending on etiology, high rates within families, with siblings having increased risk of 3 to 24 times higher than the general population |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Depending on etiology, first-degree relatives should generally have an echocardiography screening |

| Sudden unexplained death | Could be a sign of undiagnosed congenital heart disease or a genetic cardiomyopathy |

| Genetic syndrome/association/sequence | |

| Aneuploidy | Trisomy 21 associated with a variety of cardiac pathologies (endocardial cushion-related pathology) |

| Turner syndrome associated with aortic valve and root anomalies | |

| Connective tissue pathologies | Marfan syndrome associated with aortic aneurysm and root dilatation |

| ≥ 3 minor structural anomalies or one major anomaly | 3 minor anomalies carry a 90% risk of a major anomaly, including structural heart disease in conditions such as Noonan syndrome, Pierre Robin sequence, osteogenesis imperfecta, VACTERL association, CATCH 22 syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, and others |

| Inborn errors of metabolism or lysosomal storage diseases | Common comorbidities include aortic and mitral valve disease, depending on the exact disease; phenylketonuria is strongly associated with congenital heart disease |

| Exposure to teratogenic medications | |

| Lithium, valproic acid and other antiepileptic drugs; mycophenolate mofetil (Cellcept), warfarin (Coumadin), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, retinoic acid, vitamin A derivatives (not topical) | U.S. Food and Drug Administration labeling contains prevalence and extent of associations that vary for each medication |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Third trimester exposures associated with an odds ratio of 15 for premature closure of the ductus arteriosus |

| Prenatal factors | |

| First-trimester maternal infections | Conotruncal (lesions that lead to abnormal ventriculo-arterial alignment) and obstructive defects are more likely; rubella is associated with persistent ductus arteriosus and pulmonary artery stenosis |

| Maternal diabetes mellitus (especially preexisting diabetes) | 3% to 5% of infants of patients who have diabetes and aortic, vascular, or endocardial problems |

| Maternal obesity | Prevalence rate ratios of aortic arch defects and transposition of the great arteries were doubled in offspring of patients with a body mass index > 40 kg per m2; atrial septal defects and persistent ductus arteriosus prevalence rate ratio increase with maternal body mass index |

| Prenatal diagnostics | Any diagnostic concern based on prenatal sonography of the heart (intracardiac foci in isolation do not constitute a concern) |

OLDER CHILDREN

| Sign or symptom | Possible cardiac disorder | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Chest pain | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy or other left ventricular outflow obstruction | < 6% of chest pain in children is from a cardiac source |

| Neonatal respiratory distress | Mixing lesions or lesions that impair pulmonary blood flow | Multiple divergent etiologies may contribute to this |

| Palpitations or audible dysrhythmia | Numerous structural cardiac pathologies are associated with ventricular dysrhythmias | Electrocardiography indicated |

| Persistent central cyanosis beyond the first 10 minutes of life or recurrent peripheral cyanosis | Numerous cardiac abnormalities can lead to decreased arterial oxygen saturation, restricted pulmonary blood flow, and subsequent cyanosis | Chest radiography and electrocardiography are diagnostically useful |

| Poor physical activity tolerance; excessive fatigue, dyspnea, or diaphoresis exertion; or signs of venous congestion | Potentially a symptom of heart failure; may worsen during feeding | Can be associated with numerous cardiac abnormalities |

| Poor weight gain, profoundly small stature, or developmental delay | Numerous genetic disorders and syndromes can be associated with cardiac anomalies | Murmurs in syndromic children should be referred |

| Sternal and anterior chest wall anomalies | Rates of congenital heart disease are two to three times higher than the general population for children with sternal anomalies | No reliable specific pathology association |

| Syncope or near-syncope | Aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and anomalous coronary artery origin | Classically exertional |

The development of a new murmur, particularly in association with fever, may indicate several possible conditions. The most common scenario would be an innocent systolic murmur from a fever-induced increase in cardiac output. Less common diagnoses such as rheumatic fever (modified Jones criteria; https://www.mdcalc.com/jones-criteria-acute-rheumatic-fever-diagnosis), endocarditis (modified Duke criteria; https://www.mdcalc.com/duke-criteria-infective-endocarditis), Kawasaki disease (https://www.mdcalc.com/kawasaki-disease-diagnostic-criteria), and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (https://www.aafp.org/afp/2021/0900/p244.html) should be considered based on their diagnostic criteria. These criteria help inform decisions in management and further diagnostic testing.15,32–34

Physical Examination

INFANTS

Vital sign anomalies of any type can indicate structural heart disease, but vital sign interpretation depends on corrected gestational age and size. Preestablished norms can serve as a guide (https://chemm.hhs.gov/pals.htm#sec2).

When assessing general appearance, the focus should be on looking for major or minor congenital anomalies. Major congenital anomalies (i.e., congenital heart disease, orofacial clefts, or spina bifida) have significant medical, surgical, or cosmetic consequences that typically require interventions, but minor anomalies (i.e., auricular tags or single palmar creases) can also be associated with congenital heart disease.35 Specifically, children with three or more minor anomalies have a 90% chance of an underlying major anomaly, including structural heart disease.36

The cardiovascular examination begins with an inspection for peripheral or central cyanosis and prominent neck veins (although they are not always visible in newborns). The examination should also include palpation of the brachial and femoral pulses and the precordium. Palpation of pulses looks for strength, symmetry, and timing to detect aortic abnormalities, notably coarctation of the aorta. Although this examination has limited sensitivity, any abnormalities in the pulse should prompt a referral to a pediatric cardiologist.37 If precordial palpation yields a cardiac thrill or substernal heave, structural cardiac anomalies are likely. Palpation of the abdomen can detect hepatomegaly, which would indicate venous congestion due to heart failure.14

Cardiac auscultation in infants should be performed with the infant in the supine position in a location with minimal ambient noise. The stethoscope’s bell and diaphragm should be used to allow detection of high- and low-frequency murmurs. Normal infant heart rates are between 100 and 160 beats per minute, making auscultation difficult. Even discerning systole from diastole accurately can be challenging in newborns with a rapid heart rate10,38; therefore, auscultation is best performed during a period of inactivity when the infant’s pulse is likely slower.

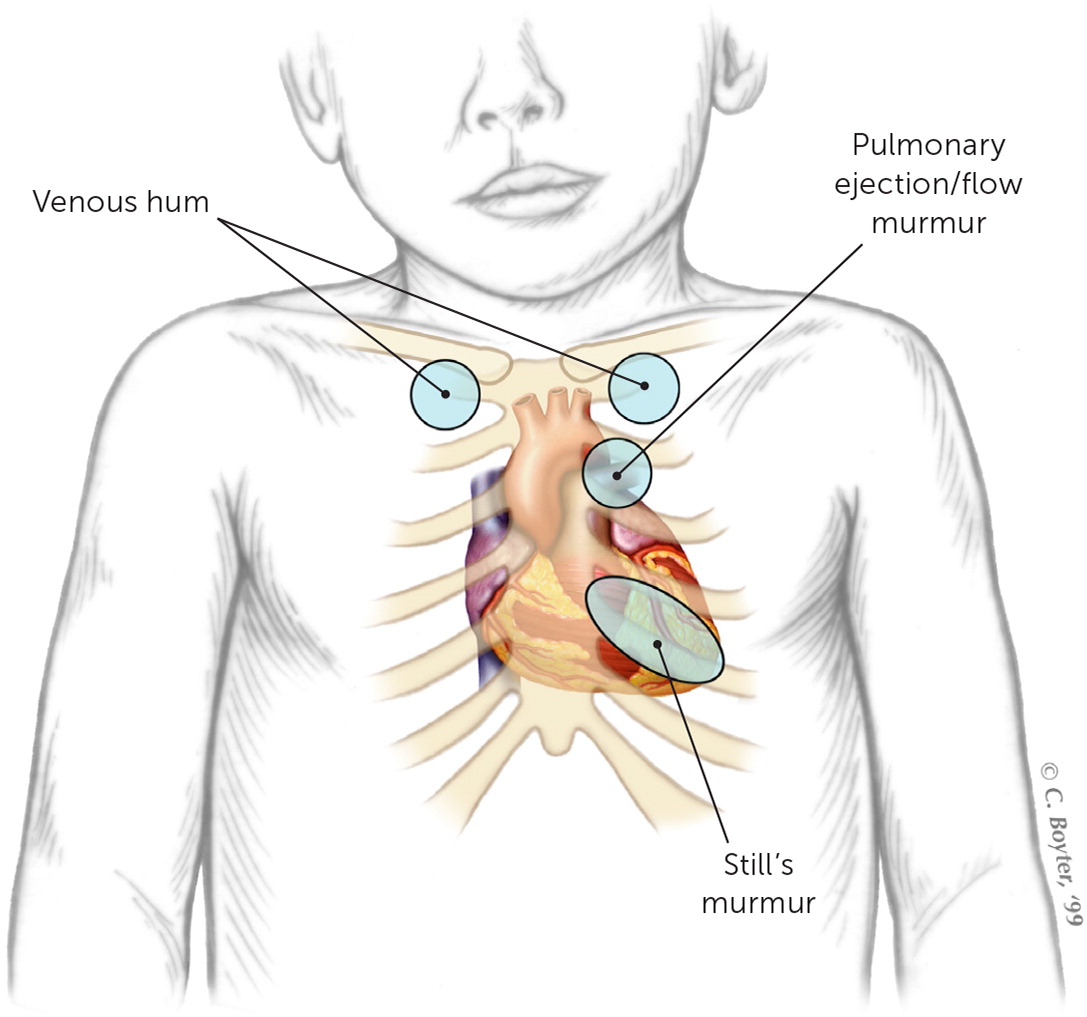

The characteristic locations of innocent murmurs are shown in eFigure A. It can be difficult to discern where in the precordium a murmur is loudest because of the smaller precordium of neonates compared with older children.

For neonates (younger than 28 days) not in distress, serial examinations can clarify the persistence of otherwise transient or innocent murmurs. The most common innocent murmurs in infants are attributed to peripheral pulmonic stenosis or closure of a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).39 Peripheral pulmonic stenosis causes a soft flow murmur best heard over the left upper sternal border with transmission to the axilla and back. The murmur typically resolves after three to six months.40 Murmurs from a PDA are systolic or continuous and are best heard at the left upper sternal border below the clavicle. If a PDA is present at birth, the murmur disappears when the PDA closes, usually by 15 hours after birth.41

OLDER CHILDREN

In children older than infancy, in addition to checking vital signs and pulses, palpation also includes noting the point of maximal impulse on the anterior chest wall in the midclavicular line with note of any shift from this position.14 A shift in position suggests malpositioning of the heart (e.g., dextrocardia if palpable on the right side of the chest) or cardiac enlargement (if palpable towards the axilla).

The physical examination in older children involves dynamic testing. Auscultation begins in the supine position, with movement to the left lateral decubitus position to assess the mitral listening area and any diastolic sounds with the diaphragm and bell of the stethoscope, followed by auscultation while transitioning to standing. In children two years and older, the complete disappearance of a murmur with standing suggests an innocent murmur with a 98% positive predictive value.42 Table 3 summarizes other dynamic tests that can help differentiate murmurs.14,43 A reasonable set of dynamic tests would include the Valsalva maneuver (causing preload reduction), squat or passive leg raise (causing preload increase), and handgrip (causing an increase in afterload).

| Dynamic maneuvers | Physiologic effect | Murmurs expected to increase | Murmurs expected to decrease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic murmurs | |||

| Valsalva or Stand from squat or Forced heavy expiration | Decrease left ventricular preload | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (likelihood ratio = 6 to 14 for these maneuvers for diagnosis) Mitral valve prolapse | Aortic stenosis Mitral regurgitation Innocent murmurs |

| Squat or passive leg raises | Increase left ventricular preload | Most murmurs increase to include mitral regurgitation and aortic stenosis | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy Mitral valve prolapse |

| Hand grip or Transient arterial occlusion (usually by blood pressure cuff) | Increase afterload | Mitral regurgitation Pulmonic stenosis Ventricular septal defects | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy Aortic stenosis Mitral valve prolapse |

| Deep or exaggerated inspiration | Increased venous return; increase in left ventricular afterload | Tricuspid regurgitation Pulmonic stenosis | No effect on other murmurs |

| Diastolic murmurs | |||

| Deep or exaggerated inspiration | Increased venous return; increase in left ventricular afterload | Tricuspid stenosis Pulmonary regurgitation (slight effect) | No effect on other murmurs |

| Hand grip or Transient arterial occlusion (usually by blood pressure cuff) | Increase afterload | Aortic regurgitation Mitral stenosis (slight increase or neutral) Ventricular septal defects | |

| Continuous murmurs | |||

| Compression of the jugular veins or Movement from sitting to supine | Decrease in jugular venous return to the superior vena cava | Not applicable | Venous hum |

Innocent Murmurs

Common innocent murmurs in childhood include Still’s murmur, pulmonary flow murmurs, and venous hum.14 Characteristics of these murmurs are described in Table 4.14,25 A useful mnemonic for identifying innocent murmurs is the seven S’s: soft, systolic, small area of involvement on precordium, short duration (typically early systolic or midsystolic sounds), single (without clicks or snaps), sweet (not harsh), and sensitive (to standing and respiratory variations).44 Venous hums, although innocent, do not abide by all of these rules, but other common innocent murmurs do.

| Murmur | Description | Proposed etiology | Common age prevalence | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Still’s murmur | Systolic Grade 1 to 2 Low frequency, such as a twanging string, musical Heard between sternal border (mid to lower position) and apex Most common murmur in children |

Unknown, theories include resonant phenomena of blood movement into the aorta, or movement across a chordae tendinae | 3 to 6 years, should disappear by adolescence | Audio file |

| Pulmonary ejection/flow murmur | Systolic Slightly grading in contrast to vibratory Heard over left upper sternal border, no significant radiation |

Exaggeration of normal ejection vibration within the pulmonary vasculature | 5 to 14 years, most common in adolescents | Audio file |

| Venous hum | Continuous, diastolic portion subtly louder Grade 1 to 2 Best heard infraclavicular and supraclavicular Only audible when patient is upright Can dissipate or exacerbate by head movements or obstruction of the ipsilateral jugular veins |

Vibration of the veins carrying the blood from the head and upper body to the superior vena cava | 3 to 6 years | Audio file |

Pathologic Murmurs

Although most murmurs in older children are innocent murmurs, certain findings suggest the possibility of a pathologic murmur. Table 5 describes these abnormal heart sounds and their implications.14,25 Table 6 describes primary features of pathologic murmurs, starting with their most audible location on the precordium, then position within the cardiac cycle, intensity, and other clinical characteristics to try and assist with classification.14,15,25,45–47

| Heart sound | Conditions suggested if abnormal | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed split S2 | Conditions that result in the aortic and pulmonary valves closing at different times (e.g., atrial septal defect, pulmonic stenosis, right bundle branch block) | S2 sound is from closure of the aortic and pulmonary valves; a fixed, widely split S2 is due to conditions that prolong right ventricular ejection or shorten left ventricular ejection |

| S3 | Conditions with ventricular dysfunction | Results from rapid filling of the ventricle; best heard at apex or lower sternal border, after the S2 in early diastole; usually loudest in dilated ventricles with decreased compliance, but can also be a normal finding |

| S4 | Conditions with decreased ventricular compliance (cardiomyopathies/ventricular hypertrophy) or overt heart failure | Audible in late diastole or presystole; an S4 is never normal |

| Thrills | Conditions such as ventricular septal defects, aortic stenosis, or patent ductus arteriosus | Precordial thrill indicates turbulent flow and is unlikely to be normal, even in the absence of an audible murmur |

| Clicks | Usually associated with aortic or pulmonic stenosis or dilatation of the aortic root or pulmonic trunk Midsystolic click is associated with mitral valve prolapse | High frequency noises that can be found in valvular pathologies |

| Where is it loudest? | When in systole? | Intensity (Levine scale*) | Other phenomena | Typical age | Likely murmur | Incidence per 10,000 live births | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic murmurs | ||||||||||||

| LLSB and apex | Midsytolic | Mid to loud (2 to 4 out of 6) | Enhanced by Valsalva maneuver and transition to standing; potentially associated with mitral regurgitation murmur | Early adolescence, depends on extent of outflow obstruction | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (audio file) | 20 | ||||||

| LUSB | Midsystolic dependent on size | Soft to loud (1 to 3 out of 6) | Radiates to back, fixed split S2, less discrete respiratory variation | Variable, dependent on size of defect | Atrial septal defect (audio file) | 5.4 | ||||||

| Apex | Holosystolic or Early blowing |

Mid to loud (2 to 3 out of 6) | Radiates to axilla, can have S3 | Congenital or acquired, most common valve impacted in rheumatic heart disease | Mitral regurgitation (audio file) | 5 | ||||||

| Apex | Late systolic with a click | Mid to loud (2 to 3 out of 6) | Midsystolic click, enhanced by Valsalva maneuver | School aged to adolescence | Mitral valve prolapse (audio file) | 5 | ||||||

| LUSB left infraclavicular area | Usually holosystolic (progresses to continuous) | Mid to loud (2 to 4 out of 6) | Machinery style; can have bounding pulses | Typically, neonate; more common in prematurity | Patent ductus arteriosus (audio file) | 5 | ||||||

| Left scapular region | Variable systolic murmurs | Soft to loud (1 to 3 out of 6) | Louder murmurs commonly from coexistent aortic valve anomaly | Neonate to adulthood | Coarctation of the aorta | 4 | ||||||

| RUSB with radiation to the carotids | Midsystolic | Mid to loud (2 to 3 out of 6) | 0.5% to 2% of children have a bicuspid aortic valve: many of these are missed neonatally If left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is present, a diagnosis is more likely in the neonatal period Can be associated with an ejection click |

Neonate to adulthood | Aortic stenosis (audio file) | 3.8 | ||||||

| LUSB | Systolic (rarely continuous) | Mixed (1 to 3 out of 6) | Loud P2 (pulmonic component of S2) when pulmonary artery hypertension is present Radiates to back and lungs |

Frequently missed; would persist beyond peripheral pulmonary stenosis | Supravalvular pulmonary stenosis (pulmonary artery stenosis) (audio file) | < 1 | ||||||

| LLSB | Holosystolic or early | Loud (2 to 3 out of 6) | Associated with hepatosplenomegaly and a pulsatile liver | Variable; Ebstein anomaly is the most common explanation | Tricuspid regurgitation (audio file) | < 1 | ||||||

| Diastolic murmurs | ||||||||||||

| LLSB | Mid-diastolic | Soft (1 to 2) | Uncommonly an anatomic stenosis, more likely functional from alternate pathology | Variable | Tricuspid stenosis | 30 | ||||||

| Apex | Early | Soft (1 to 2) | More commonly associated with rheumatic heart disease | Toddlers (> 12 months) and adolescents | Mitral stenosis (audio file) | < 1 | ||||||

Pulse Oximetry

All infants, with or without heart murmurs, should be screened for critical congenital heart disease using pulse oximetry.48,49 The procedure involves a pulse oximetry measurement in the right upper extremity and either of the lower extremities. Measurement results are considered abnormal if the oxygen saturation is less than 90%, if saturation is less than 95% in both extremities across three measurements separated by one hour, or if there is a greater than 3% upper and lower extremity difference on three measurements each separated by one hour.50 Other protocols exist across states and health care organizations. A combination of pulse oximetry and physical examination correctly identifies many critical congenital lesions.51,52

A Cochrane review of 21 studies involving more than 450,000 participants demonstrated that out of 10,000 seemingly healthy infants, six had clinically unsuspected critical congenital heart disease, and pulse oximetry screening would detect five of those six cases. However, false-positive results are common if the procedure is performed too early in life. About 14 children out of the 10,000 had a false-positive result when tested within the first 24 hours after birth, but there were only two false positives when testing occurred 24 hours or more after birth.53 Therefore, screening should ideally take place 24 hours after birth but before discharge.48–50,53–55

Cardiology Referral

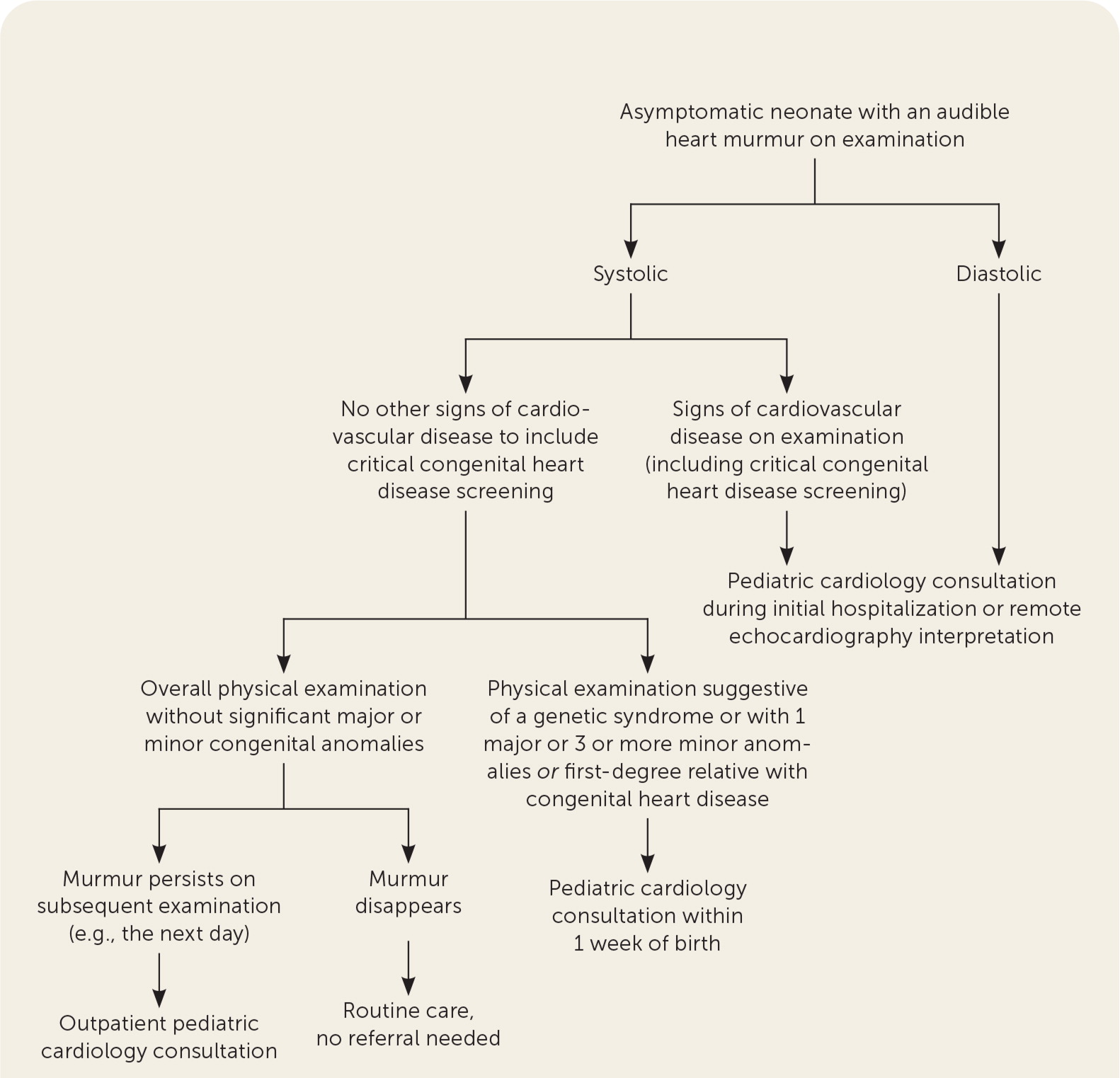

A step-by-step approach for the evaluation of murmurs in infants who are nonsyndromic, including referral indications, is provided in Figure 1. Pediatric cardiology referral should occur for murmurs during the initial hospitalization when signs or symptoms of cardiac disease are present, the critical congenital heart screening results are abnormal, syndromic features are present, there is a history of abnormal fetal echocardiography, or a first-degree relative with congenital heart disease. Referral is also recommended for any murmur that persists throughout serial examinations in the newborn nursery and persists at the time of discharge. Consultation with pediatric cardiology is the appropriate first step instead of echocardiography or other testing and should occur within the first week of life. Studies show that neonatal murmurs are difficult for noncardiologists to classify,38 but pediatric cardiologists outperform other clinicians in their ability to classify murmurs as innocent or pathologic.56,57 Although studies confirm that echocardiography can diagnose critical congenital heart disease,19 cost assessments support referral first, instead of an echocardiography-first strategy, reducing overall costs of the evaluation with similar outcomes.20

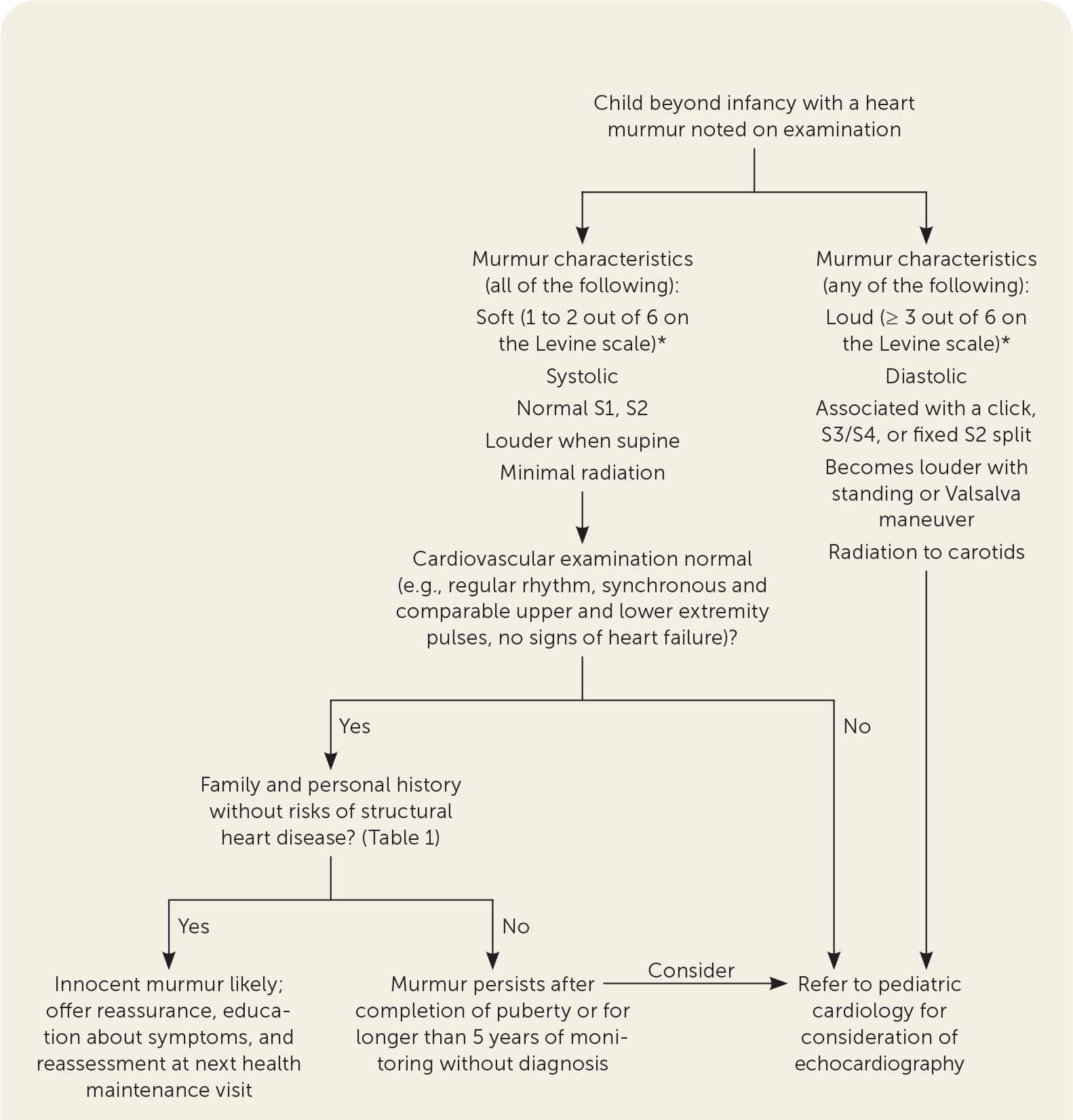

Figure 2 outlines the approach to evaluating heart murmurs in children beyond infancy. Murmur characteristics dictate the necessity for referral. Most murmurs in asymptomatic children meet the criteria for an innocent murmur and do not require a referral. When the history and examination suggest an innocent murmur in children beyond infancy, monitoring with serial examinations at wellness visits and clearance for participation in sports are appropriate. However, children with signs or symptoms of cardiac disease or whose heart sounds and murmurs have characteristics of pathologic murmurs should be referred to a pediatric cardiologist.

Echocardiography

A multispecialty panel developed appropriate criteria for outpatient echocardiography in children with a heart murmur.58 Based on these criteria, echocardiography is rarely appropriate for patients with an innocent-sounding murmur without significant signs or symptoms of cardiovascular disease and no family history of significant pathology. Echocardiography is appropriate for a murmur associated with signs or symptoms of cardiovascular disease or with pathologic sounding murmurs. However, as above, a cardiology referral is often the more appropriate approach.

Other Studies

Commonly considered additional studies include electrocardiography, chest radiography, and four-point blood pressure assessments.20 Four-point blood pressure measurement is often performed in infants with murmurs to assess for extremity blood pressure differences, although this test offers poor specificity at a 5 mm Hg cutoff (59.8%) and poor sensitivity at a 15 mm Hg cutoff (21.7%).59 Although exceptions exist, the routine use of these tests in the evaluation of heart murmurs in children who have no symptoms or other signs of heart disease is not cost-effective, even when a pathologic murmur is suspected based on examination.20,60 One study demonstrated that the more cost-effective approach to evaluation of a suspected pathologic murmur is a referral to a pediatric cardiologist before performing these ancillary tests.20 Another study found that chest radiography and electrocardiography results were more likely to cause misclassification of the murmur as innocent or pathologic.61 When consultation is not readily available, these studies could help identify the urgency for a referral.

Emerging Technologies

High-fidelity recordings with graphic representations of the auscultatory findings and computer-aided analyses of murmurs (i.e., phonocardiography) are helpful for education and remote auscultation.62,63 Similar to the automated interpretation of electrocardiograms, this technology can improve diagnostic accuracy. One automated system classified murmurs as innocent or pathologic with 87% sensitivity and 100% specificity and 94% accuracy overall compared with echocardiography.64 A successful algorithm has been developed for identification of Still’s murmur.65 Several systems have U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of their artificial intelligence algorithms and stethoscope technology. Trials looking for the effectiveness of these devices to reduce initial consultations are ongoing,66 and they could serve an important role in remote consultation and diagnosis.

Resources for murmur education and evaluation for clinicians interested in improving ausculatory skills are listed in eTable A.

| AccessMedicine Auscultation Classroom https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/multimedia.aspx#1413 |

| Association of American Medical Colleges MedEdPortal - Professional Skill Builder: Mastering Cardiac Auscultation in Under 4 Hours https://www.mededportal.org/doi/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10577 |

| Eko Academy https://www.ekohealth.com/academy |

| eMurmur https://emurmur.com/downloads |

| MurmurQuiz https://murmurquiz.org |

| Physical Diagnosis PDX https://physicaldiagnosispdx.com/card-tutorial https://physicaldiagnosispdx.com/cardiology-multimedia-new |

| Teaching Heart Auscultation to Health Professionals https://teachingheartauscultation.com |

| Thinklabs One Digital Stethoscope Heart Sound Library https://www.thinklabs.com/heart-sounds-old |

| University of Michigan Heart Sound & Murmur Library http://www.med.umich.edu/lrc/psb_open/html/repo/primer_heartsound/primer_heartsound.html |

| University of Washington Department of Medicine Advanced Physical Diagnosis Learning and Teaching at the Bedside – Demonstrations: Heart Sounds & Murmurs http://depts.washington.edu/physdx/heart/demo.html |

Recordings are available in Harvey W, Beydneck J, Canfield D. Clinical Heart Disease 2011, Fairfield, NJ: Laennec Publishing.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Frank and Jacobe25 and McConnell, et al.67

Data Sources: A search was completed in Essential Evidence Plus, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, the Cochrane database, PubMed, and the Trip database. Keywords searched were cardiac auscultation, heart murmur, critical congenital heart disease, congenital heart disease, stethoscope, innocent vs. pathologic murmur, innocent murmur, pathologic murmur, murmur, pediatric cardiology, pediatric echocardiography, telehealth, teleauscultation, and appropriate use criteria. Search dates: February 27, 2021; April 6, 2021; and November 23, 2021.

The authors thank Dave Aurigemma, MD, for assistance in development of the algorithms.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.