Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(3):272-280

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Thalassemia is a group of autosomal recessive hemoglobinopathies affecting the production of normal alpha- or beta-globin chains that comprise hemoglobin. Ineffective production of alpha- or beta-globin chains may result in ineffective erythropoiesis, premature red blood cell destruction, and anemia. Chronic, severe anemia in patients with thalassemia may result in bone marrow expansion and extramedullary hematopoiesis. Thalassemia should be suspected in patients with microcytic anemia and normal or elevated ferritin levels. Hemoglobin electrophoresis may reveal common characteristics of different thalassemia subtypes, but genetic testing is required to confirm the diagnosis. Thalassemia is generally asymptomatic in trait and carrier states. Alpha-thalassemia major results in hydrops fetalis and is often fatal at birth. Beta-thalassemia major requires lifelong transfusions starting in early childhood (often before two years of age). Alpha- and beta-thalassemia inter-media have variable presentations based on gene mutation or deletion, with mild forms requiring only monitoring but more severe forms leading to symptomatic anemia and requiring transfusion. Treatment of thalassemia includes transfusions, iron chelation therapy to correct iron overload (from hemolytic anemia, intestinal iron absorption, and repeated transfusions), hydroxyurea, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and luspatercept. Thalassemia complications arise from bone marrow expansion, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and iron deposition in peripheral tissues. These complications include morbidities affecting the skeletal system, endocrine organs, heart, and liver. Life expectancy of those with thalassemia has improved dramatically over the past 50 years with increased availability of blood transfusions and iron chelation therapy, and improved iron overload monitoring. Genetic counseling and screening in high-risk populations can assist in reducing the prevalence of thalassemia.

Thalassemia is a group of autosomal recessive hemoglobinopathies involving ineffective production of normal alpha- or beta-globin chains, which can lead to ineffective erythropoiesis, premature red blood cell destruction, and anemia. Other common hemoglobinopathies (e.g., sickle cell disease) arise from production of abnormal globin chains. This article summarizes key evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of thalassemia for primary care physicians.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Avoid using hemoglobin to evaluate patients for iron deficiency in susceptible populations. Instead, use ferritin. | American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science |

| Do not repeat hemoglobin electrophoresis (or equivalent) in patients who have a prior result and who do not require therapeutic intervention or monitoring of hemoglobin variant levels. | American Society for Clinical Pathology |

Epidemiology

Thalassemia prevalence is highest in Africa, India, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Incidence in these regions may be decreasing because of prevention programs involving premarital and preconception counseling and testing.1–4

Approximately 5% and 1.5% of the world population are carriers of alpha- and beta-thalassemia, respectively.1,4

Thalassemia affects 6 per 100,000 conceptions in the Americas.5 Data specific to the United States are lacking, but California has an estimated incidence of 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 55,000 for alpha- and beta-thalassemia, respectively.4,6

Pathophysiology

Hemoglobin (Hb) comprises an iron-containing heme ring and four globin chains: two alpha and two nonalpha (beta, delta, gamma).7–9 See diagram at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2009/0815/p339.html#afp20090815p339-f1. HbF is the most common type in newborns. By six months of age, HbA is predominant. Clinically significant thalassemia presents with reduced HbA production.7,8

Table 11,10,11 and Table 210–12 detail alpha- and beta-thalassemia subtypes.

| Subtype | Chromosome 16 mutation* | Signs and symptoms | Hb and MCV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silent carrier (alpha-thalassemia minima) | One of four gene deletions | Normal Hb and hematocrit, asymptomatic | Normal |

| Trait (alpha-thalassemia minor) | Two of four gene deletions† | Microcytosis, possibly mild anemia, asymptomatic | Hb slightly subnormal; MCV < 80 μm3 (80 fL) |

| Deletional HbH disease (alpha-thalassemia intermedia) | Three of four gene deletions | Mild to moderate anemia, ineffective erythropoiesis, skeletal abnormalities‡ | Hb = 6.9 to 10.7 g per dL (69 to 107 g per L); MCV = 46 to 76 μm3 (46 to 76 fL) |

| Nondeletional HbH disease (Hb Constant Spring) | Mutant allele causing reduced alpha-globin activity | More severe phenotype than deletional HbH disease; moderate to severe anemia, splenomegaly, gallstones, decreased bone density, growth retardation; often requires transfusion | Hb = 3.8 to 8.7 g per dL (38 to 87 g per L); MCV = 48.7 to 80 μm3 (48.7 to 80 fL) |

| Alpha-thalassemia major with Hb Bart’s disease | Four of four gene deletions | Nonimmune hydrops fetalis, usually fatal without treatment | Transfusion dependence if surviving |

| Subtype | Chromosome 11 mutation* | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Beta-thalassemia trait | Single gene defect | Asymptomatic |

| Beta-thalassemia intermedia | Two genes defective (mild to moderate impairment in beta-globin production) | Symptoms similar to beta-thalassemia major but with variable severity; may have mild to moderate anemia, and may require intermittent or regular transfusions |

| Beta-thalassemia major | Two genes defective (severe impairment in beta-globin production) | Ineffective erythropoiesis, resulting in severe anemia, gallstones, skeletal abnormalities† (due to bone marrow expansion), hepatosplenomegaly (causing abdominal distension), jaundice, and pallor; requires lifelong blood transfusions starting by six to 24 months of age |

Screening and Prevention

A complete blood count should be performed in all pregnant patients to screen for thalassemia. A low mean corpuscular volume warrants Hb electrophoresis. It is also reasonable to obtain Hb electrophoresis for those in high-risk ethnic groups (African, West Indian, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Southeast Asian).13

Preconception genetic counseling and testing should be discussed with patients who have risk factors (first-degree relative with thalassemia, history of stillbirth, high-risk ethnicity, and low mean corpuscular volume).13

Prenatal diagnosis is performed via chorionic villus sampling at 10 to 12 weeks’ gestation or amniocentesis after 15 weeks’ gestation.13

Newborn screening for thalassemia varies by state. HbSS, beta-thalassemia/HbS, and HbS/C are the only hemoglobinopathies considered to be core conditions on the U.S. Recommended Uniform Screening Panel. Other hemoglobinopathies are listed as secondary conditions, but neither alpha- nor beta-thalassemia is included on this list.14

Diagnosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Thalassemia is generally asymptomatic in trait and carrier states.10,11

Moderate to severe microcytic anemia can occur in intermediate and major types of thalassemia, presenting as fatigue, lightheadedness, and syncope, as well as poor growth in children. Active hemolysis may cause hyperbilirubinemia, jaundice, and gallstones.10

Erythropoietin stimulation from chronic anemia may induce signs of bone marrow expansion (pseudotumors, frontal bossing, maxillary hypertrophy, malar prominence, depressed nasal bridge) and extramedullary hematopoiesis (hepatosplenomegaly).10,11

Nonimmune hydrops fetalis occurs in alpha-thalassemia major/Hb Bart’s disease.11

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Thalassemia should be considered in patients with microcytic anemia.10

The differential diagnosis for microcytic anemia includes iron deficiency anemia, lead poisoning, sideroblastic anemia, anemia of chronic disease, copper deficiency, zinc toxicity, and hemoglobinopathies.15

Initial evaluation includes a complete blood count and indices, peripheral smear, serum ferritin level, and blood lead level (Table 3).10,11,16–18

Peripheral smear in patients with thalassemia will typically show microcytosis, hypochromia, poikilocytosis, and target cells.10,11,17

Normal red blood cell distribution width with microcytosis may suggest thalassemia. However, it is not sensitive or specific enough to differentiate thalassemia from iron deficiency anemia and should be used only in the context of other laboratory findings.16

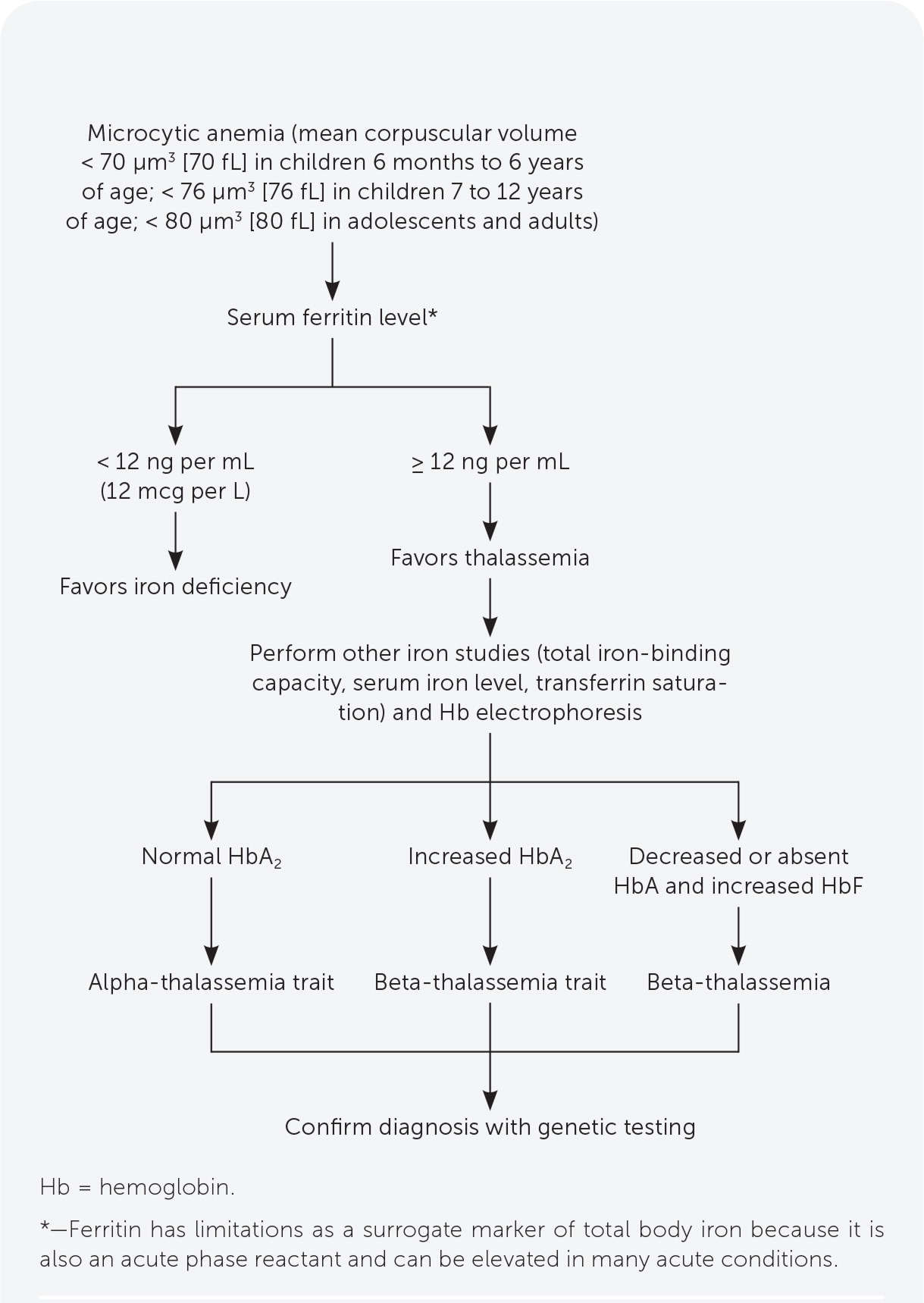

Serum ferritin measurement is the best initial test to evaluate for iron deficiency. Thalassemia should be suspected in patients with microcytic anemia and normal or elevated ferritin levels (Figure 1).10,15,19 Other iron-related studies can be useful when the ferritin level is intermediate to low or normal but suspicion for iron deficiency anemia is still present.10,19

Decreased HbA on electrophoresis is characteristic of thalassemia. Other findings include elevated HbA2 in beta-thalassemia, and Hb Bart’s disease in alpha-thalassemia major.10,17 Hb electrophoresis findings are normal in alpha-thalassemia trait and carrier states (Table 4).10,20–22

Genetic testing should be used to confirm the diagnosis and identify mutations that correlate with severity of disease.10,17

Thalassemia can present with other hemoglobinopathies (Table 5).9

Once thalassemia is diagnosed, the degree of iron overload can be investigated further with T2*-weighted cardiac or R2*-weighted liver magnetic resonance imaging, or rarely liver biopsy.1,3,10,11

Given the varied clinical manifestations of thalassemia subtypes, the Thalassaemia International Federation distinguishes between transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT) and non–transfusion-dependent thalassemia (NTDT). Treatment decisions are more often based on this classification than on subtype classification (i.e., carrier, trait, minor, intermedia, major).10,11

| Iron deficiency | Alpha-thalassemia | Beta-thalassemia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCV | Low: < 70 μm3 (70 fL) in children 6 months to 6 years of age; < 76 μm3 (76 fL) in children 7 to 12 years of age; < 80 μm3 (80 fL) in adolescents and adults | Low: < 80 μm3, but often < 75 μm3 (75 fL) | Low: < 80 μm3, but often < 75 μm3 |

| Red blood cell distribution width | High: > 15% | Normal | Normal, can be high |

| Ferritin | Low: < 12 ng per mL (12 mcg per L) | Normal to elevated | Normal to elevated |

| Mentzer index (MCV/red blood cell count) in children | ≥ 13 | < 13 | < 13 |

| Peripheral smear | Microcytosis, hypochromia; may progress to poikilocytosis as anemia worsens | HbH can be seen in severe forms | Microcytosis, hypochromia, anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, target cells, nucleated red blood cells, increased reticulocytes, basophilic stippling |

| Hb electrophoresis | Normal (may have diminished HbA2) | Adult carrier or trait: normal Intermedia: HbH (up to 30%), decreased HbA2 Newborns: may have HbH or Hb Bart’s disease | Increased HbA2, or decreased or absent HbA and likely increased HbF |

| Subtype | HbA | HbA2 | HbF | HbH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal/alpha-thalassemia trait | > 95% | 2% to 3.5% | < 1% | Absent |

| Beta-thalassemia trait | > 90% | 3.5% to 9% | 0.1% to 5% | Absent |

| Beta-thalassemia major | Marked decrease, may be absent | > 4% | 10% to 50%, may be up to 100% | Absent |

| HbH disease | Typically below normal | < 4%, below normal | 5% to 25% | 0.8% to 40% |

| Hemoglobinopathy | Thalassemia | Genetics representation | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| HbC | Beta-thalassemia with severely reduced beta-globin synthesis | HbC/β0 | Microcytic anemia |

| Beta-thalassemia with mildly reduced beta-globin synthesis | HbC/β+ | Asymptomatic to mild anemia | |

| HbE (beta-globin variant) | Beta-thalassemia trait | HbE/β+ | Variable; mild to moderate anemia |

| Beta-thalassemia | HbE/β0 | Similar to beta-thalassemia intermedia or major, can be severe and transfusion dependent | |

| HbS | Beta-thalassemia with severely reduced beta-globin synthesis | HbS/β0 | Almost identical to sickle cell disease (HbSS) in symptoms and on Hb electrophoresis (low mean corpuscular volume can help distinguish HbS/β0 from HbSS) |

| Beta-thalassemia with mildly reduced beta-globin synthesis | HbS/β+ | Milder symptoms (i.e., less pain and hemolysis) and milder anemia |

Treatment

TRANSFUSION THERAPY

Patients with TDT require regular transfusions, usually scheduled every two to five weeks.10 Beta-thalassemia major, nondeletional HbH disease, survived Hb Bart’s disease, and severe HbE/beta-thalassemia are typically considered TDTs.10

Those with NTDT may require occasional transfusions for symptomatic anemia, during pregnancy, before surgery, or during serious infections. They may ultimately need chronic transfusions as anemia, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and other complications worsen or to promote growth.3,11

Repeated transfusions increase the risk of alloimmunization, other transfusion-associated reactions, transfusion-related infections, and iron overload.10,24

| Transfusion |

| Confirmed Hb level less than 7 g per dL (70 g per L) or In the absence of the above: Poor growth or pubertal development Significant bone pathology (fractures or deformities of facial bones or the spinal column due to increased bone marrow hematopoiesis) Significant extramedullary hematopoiesis (leading to hepatosplenomegaly) Significant anemia-related detriments to school or work performance, exercise tolerance, or quality of life |

| Targets of therapy include: Pretransfusion Hb level of 9 to 10.5 g per dL (90 to 105 g per L) Posttransfusion Hb level up to 11 to 12 g per dL (110 to 120 g per L) |

| Transfusion has been used in utero for Hb Bart’s disease to prevent hydrops fetalis |

| Chelation therapy |

| At least 2 years of age and at least one of the following: More than 10 to 12 transfusions Serum ferritin level > 1,000 ng per mL (1,000 mcg per L) in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia; greater than 800 ng per mL (800 mcg per L) in patients with non–transfusion-dependent thalassemia Liver iron concentration greater than 3 mg per g determined by liver R2*-weighted MRI Myocardial iron concentration less than 20 ms determined by cardiac T2*-weighted MRI |

IRON CHELATION THERAPY

Iron chelation therapy corrects iron overload caused by hemolytic anemia, increased intestinal iron absorption, and repeated transfusions, and is recommended for TDT if ferritin levels exceed 1,000 ng per mL (1,000 mcg per L) and for NTDT when ferritin levels exceed 800 ng per mL (800 mcg per L).3,10 Table 6 lists its indications.1,3,10,11,23

Retrospective observational studies have reported decreased overall mortality and cardiac-related mortality with chelation therapy. Mortality appears to be reduced when the therapy is started earlier in life.25 Small randomized controlled and observational studies have shown that chelation therapy effectively reduces liver and myocardial iron concentrations.26,27

eTable A summarizes iron chelation therapy options.

| Chelating agent | Age of use | Route | Contraindications | Adverse effects | Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferoxamine (Desferal) | > 2 years (first-line) | Subcutaneous or parenteral infusion over 8 to 12 hours, 5 to 7 days per week | Pregnancy (although it has been used in the second and third trimesters) Hypersensitivity | Infusion site reactions Ophthalmic issues (diminished visual acuity, color vision, night vision; lens opacities) Hearing issues (sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus) Growth issues (growth retardation, genu valgum) Zinc deficiency Septicemia (Yersinia, Klebsiella) Renal dysfunction | Annual eye examination (including electroretinography if on high doses) Annual hearing examination Annual zinc measurement ALT measurement monthly Renal function monthly |

| Deferasirox | > 2 years (first-line) | Oral (tablet) taken once daily | Pregnancy Hypersensitivity Creatinine clearance < 60 mL per min per 1.73 m2 (1 mL per second per m2) Liver dysfunction or renal failure | Gastrointestinal issues (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, gastric bleeding, ulcers) Increased serum ALT Increased creatinine Proteinuria | Liver function testing every 2 weeks for 1 month, then monthly Weekly renal function panel and urinalysis during first month, then monthly Quarterly CBC with differential Annual eye and hearing examinations |

| Deferiprone (Ferriprox) | > 6 years (second-line) | Oral (tablet or liquid) taken 2 or 3 times daily | Pregnancy History of neutropenia or at risk of cytopenia Hypersensitivity, including Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Gastrointestinal issues (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea) Increased serum ALT Arthralgias Neutropenia Agranulocytosis | Weekly CBC during therapy (monitor neutrophil count) ALT measurement monthly Consider annual eye and hearing examinations if used in combination with deferoxamine |

OTHER THERAPIES

Hydroxyurea promotes HbF production, and small observational studies have shown an association between this therapy and decreased transfusion frequency in beta-thalassemia major and intermedia.11,28 However, stronger evidence is lacking.29

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is potentially curative for TDT.10,30 Ideal candidates are younger than 12 years with a sibling donor who is a human leukocyte antigen match to the patient.3,10 An unrelated matched donor could be considered. Prospective studies have shown that with transplantation, overall survival is greater than 90% and thalassemia-free survival is greater than 80%.31

Genotyping and evaluation for transplantation (including human leukocyte antigen typing) should be ordered for all patients once, before 12 years of age if possible. In patients 12 years or older, gene therapy may be considered.

Luspatercept (Reblozyl) is an activin receptor ligand trap that promotes erythropoiesis and decreases overall transfusion burden in beta-thalassemia. In a phase 3 randomized trial, luspatercept had a number needed to treat of 6 for one adult with TDT to have a 33% reduction in transfusion burden.32

Experimental gene therapies can induce normal beta-globin production or reactivate HbF production in patients with TDT and could dramatically reduce the need for long-term transfusions.33,34

Complications of Thalassemia

Complications develop from uncontrolled chronic anemia, bone marrow expansion, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and iron overload. Iron deposition in peripheral tissues causes oxidative stress, free radical production, and organ dysfunction.1,3

eTable B summarizes thalassemia-associated complications and recommended monitoring and treatment for each.

| Complications | Monitoring tests | Ages to test | Frequency | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | Complete blood count with differential | All | Every 6 months Monthly if receiving transfusions | Pretransfusion Hb goal: 9 to 10.5 g per dL (90 to 105 g per L) Posttransfusion Hb goal: 11 to 12 g per dL (110 to 120 g per L) |

| Cardiac complications, such as arrhythmia and heart failure | T2*-weighted cardiac MRI | Starting at 10 years | Every 2 years if T2 ≥ 30 ms Annually if T2 ≥ 10 ms and < 30 ms Every 6 months if T2 < 10 ms | Iron chelation therapy has been shown to reverse cardiac dysfunction |

| Echocardiography and electrocardiography | Starting at 10 years | Annually if LVEF ≥ 56% Every 4 to 6 months if LVEF < 56% | — | |

| Endocrine disorders | Hypothyroidism: thyroid-stimulating hormone | ≥ 9 years | Annually | Treat per society and local institutional standards |

| Hypoparathyroidism: calcium, phosphate, vitamin D, and parathyroid hormone | ≥ 9 years | Annually | — | |

| Diabetes mellitus: fasting glucose or A1C | ≥ 9 years | Annually | — | |

| Adrenal insufficiency: corticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone) stimulation test | ≥ 9 years in those with iron overload or growth hormone deficiency | Every 1 to 2 years | — | |

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis | Physical examination to assess for facial and bone deformities, pseudotumors, and hepatosplenomegaly Imaging based on clinical suspicion | All | Every visit | Pseudotumors may improve with transfusions, hydroxyurea, irradiation, or surgery Splenectomy may be indicated for clinically significant splenomegaly (symptomatic splenomegaly, hypersplenism with clinically significant cytopenias, or iron overload from frequent transfusions that cannot be managed with chelation therapy) Patients should be immunized against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis before splenectomy |

| Dental examination | All | Annually | Evaluate for facial deformities affecting teeth, palate, and mandible | |

| Growth delay | Height (measure standing and sitting height when possible) Weight Head circumference | All | Annually Every 3 to 6 months during puberty or long-term transfusion therapy | If growth delay (< 3rd percentile) is identified, IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 measurements and growth hormone stimulation testing should be performed Consider other causes of growth delay in workup (chelation therapy toxicity, other hormonal or nutritional disorders) Treat per society and local institutional standards |

| Bone age radiography | 9 to 17 years | Annually | — | |

| Leg ulcers | Skin examination | All | Every visit | More common in patients with NTDT Treat per society and local institutional standards; consider referral to wound care specialist |

| Liver dysfunction, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma | Liver function tests (including AST, ALT, bilirubin) | All | Every 3 to 6 months Monthly if undergoing transfusion or if AST or ALT > 5 times the upper limit of normal | Chelation therapy has been shown to reverse hepatic fibrosis and inflammation |

| R2*-weighted MRI | Starting at 10 years | Every 2 years if LIC < 3 mg per g Annually if LIC is 3 to 15 mg per g Every 6 months if LIC > 15 mg per g | An LIC of 3 to 7 mg per g is considered an adequate goal in treating iron overload in patients with thalassemia | |

| Liver ultrasonography | ≥ 18 years | Annually Every 6 months if diagnosed with cirrhosis | Ultrasonography can also assess for portal hypertension, gallstones, or biliary disease Transient elastography can identify and determine the stage of fibrosis | |

| Alpha fetoprotein | ≥ 40 years or if cirrhosis is diagnosed | Every 6 to 12 months | — | |

| Osteoporosis | Bone mineral density with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry | ≥ 10 years | Every 1 to 2 years | Encourage physical activity, smoking cessation, and adequate calcium intake for prevention Initiate bisphosphonate therapy with calcium, vitamin D, and zinc supplementation for diagnosed osteoporosis Hormone therapy, transfusions, iron chelation therapy, and hydroxyurea, if indicated, may prevent osteoporosis |

| Pubertal delay | Tanner staging | 9 to 17 years | Annually | Treat pubertal delay per society and local institutional standards |

| Menstrual history | ≥ 9 years | Annually | — | |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, testosterone, estradiol | ≥ 9 years | Annually | Obtain if concerned for pubertal delay or secondary hypogonadism | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Echocardiography | Starting at 10 years | Every 1 to 2 years | Tricuspid valve velocity > 3 m per second necessitates cardiac catheterization to confirm diagnosis Potentially beneficial treatments include transfusions, hydroxyurea, sildenafil (Revatio), anticoagulation, and controlling iron overload |

| Reproductive health, infertility and pregnancy | Assess for infertility | ≥ 14 years | Annually | 80% to 90% of patients with TDT have hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, although fertility may be possible with induction of ovulation or spermatogenesis Assistive reproduction technology may be necessary |

| Assess patient’s desire for pregnancy | Child-conceiving age | Annually | Ideally, pregnancy in patients with thalassemia should be planned because of the potential risks to mother and child Discuss contraception if pregnancy is not desired Prepregnancy Provide counseling on the risks of pregnancy and methods for prenatal diagnosis Optimize health and risk management (assess iron overload status; cardiac, liver, thyroid function; viral infection status; appropriate immunizations) Discontinue iron chelation therapy (deferoxamine [Desferal] may be used in second and third trimesters) Discontinue bisphosphonates (6 months prior), hormone therapy, hydroxyurea, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; switch anticoagulants to heparins Start folic acid supplementation During pregnancy Assess cardiac, liver, and thyroid function each trimester Screen for gestational diabetes at 16 and 28 weeks’ gestation Monitor fetal growth with serial ultrasonography beginning at 24 to 26 weeks More frequent transfusions may be needed Thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin; aspirin for patients who have had a splenectomy After pregnancy When the patient is no longer breastfeeding, bisphosphonates, hormone therapy, and iron chelation therapy may be restarted (deferoxamine is safe during breastfeeding) Thromboprophylaxis for 7 days after vaginal delivery or 6 weeks after cesarean delivery Discuss contraception | |

| Systemic iron overload | Ferritin | All | Every 3 months | Ferritin ≥ 1,000 ng per mL (1,000 mcg per L) in patients with TDT or ≥ 800 ng per mL (800 mcg per L) in patients with NTDT warrants chelation therapy |

| Thrombosis | Assess risk at time of inpatient admission, surgery, or pregnancy | All | As necessary | Higher risk in adults and in individuals with splenectomy, beta-thalassemia intermedia, history of thrombosis, pulmonary hypertension, platelet count > 500 × 103 per μL (500 × 109 per L), or Hb < 10 g per dL (100 g per L) Consider prophylactic anticoagulation in high-risk patients Consider aspirin in patients with NTDT and splenectomy if platelet count > 500 × 103 per μL |

| Transfusion-related infections | Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV | All, if receiving transfusions | Annually | Patients should be immunized against hepatitis A and B before initiating transfusions Treat infections per society and local institutional standards |

SKELETAL ABNORMALITIES

Stimulated expansion of bone marrow causes abnormal bone growth, including enlarged craniofacial bones and spinal deformities that can compress spinal nerves.3,35,36

Disorders of skeletal growth, including delayed sexual maturation and endocrine disorders, are common in patients with thalassemia and result in shortened stature, increased bone turnover, and lowered bone mineral density.3,35

Despite adequate transfusions and iron chelation therapy, 40% to 50% of patients with beta-thalassemia major have osteopenia or osteoporosis.37 Physical activity, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and hormone therapy for specific endocrine disorders are preventive strategies.10

Bisphosphonates and zinc supplementation can improve bone mineral density in patients with thalassemia and osteoporosis, and calcium and vitamin D are also recommended.10,35,37

ENDOCRINE DISORDERS

Diabetes mellitus arises from pancreatic iron deposition, impairing insulin production, and peripheral tissue iron deposition, impairing insulin utilization.38

Nearly 44% of patients with beta-thalassemia major have nondiabetes endocrine disorders, most commonly hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, and hypoparathyroidism.38

Growth hormone deficiency occurs in 8% to 14% of U.S. patients with TDT. Growth hormone treatment in children may mitigate the effects of short stature.39

Primary or secondary amenorrhea can occur in patients with TDT.24

Since the introduction of iron chelation therapies in 1975, the prevalence of hypogonadism, diabetes, and hypothyroidism has diminished in patients with thalassemia.10

CARDIAC COMPLICATIONS

Worldwide, 25% of patients with beta-thalassemia major have cardiac iron overload, and 42% have cardiac complications such as electrocardiogram abnormalities, myocardial fibrosis, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, arrhythmias, heart valve disease, pericarditis, and myocarditis.3,10,40

The adoption of T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging to detect cardiac iron overload in the early 2000s, along with effective iron chelation therapies, is estimated to have reduced cardiac mortality by 71% among patients with beta-thalassemia major in the United Kingdom.41

Iron chelation therapy is the most widely accepted approach for preventing and treating cardiac iron overload.10 Expert opinion, based on low-quality evidence, suggests that chelation therapy can improve asymptomatic and symptomatic heart disease and reverse early left ventricular dysfunction.10 Additionally, lower ferritin levels are associated with prolonged survival and a lower probability of heart failure.42

SPLENOMEGALY

An enlarged spleen results from splenic hyperfunctioning to remove defective red blood cells and erythropoietin stimulation to promote hematopoiesis.43

Splenectomy can improve baseline Hb level by 1 to 2 g per dL (10 to 20 g per L) and reduce transfusion frequency. Splenectomy carries perioperative risks and higher long-term risk of venous thromboembolism, pulmonary hypertension, and encapsulated organism infections.43

Splenectomy is reserved for select indications: iron overload from frequent transfusions that cannot be controlled with iron chelation therapy, hypersplenism with clinically significant cytopenias, and symptomatic splenomegaly. Splenectomy should be avoided in children younger than five years because of the high risk of sepsis postsplenectomy.10

LIVER DISEASE

Up to 15% of U.S. patients with TDT will develop liver disease due to iron deposition, including cirrhosis (2% to 7%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (0.75% to 3.5%).24

Liver iron concentration should be measured regularly by R2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging starting at 10 years of age.3,10

If liver iron concentration increases while on chelation therapy, patient compliance should be reviewed, and dosing, frequency, or the chelating agent may need to be changed.10

Frequent transfusions increase the risk of hepatitis C and other bloodborne pathogens.24

THROMBOTIC EVENTS

Observational studies have identified an increased risk of thromboembolism, particularly stroke, in patients with beta-thalassemia intermedia and major.44

Currently, no guidelines recommend antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy for primary prevention of thrombotic events in nonpregnant patients. The Thalassaemia International Federation does recommend thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin in pregnant patients with TDT or NTDT, and aspirin in pregnant patients who have had a splenectomy.10,11

Prognosis

Patients with alpha-thalassemia intermedia (deletional HbH disease) typically have a normal lifespan and may have mild anemia and splenomegaly; a small proportion will require transfusions. Patients with nondeletional HbH disease more often require transfusions, may have TDT, and have more complications.1

Most newborns with Hb Bart’s hydrops fetalis who did not receive intrauterine transfusion die shortly after birth. Intrauterine transfusion can increase survival.45 One study demonstrated an increased survival rate from 40% between 1987 and 1992 to 100% between 2011 and 2016.46 Current trials are investigating the use of intrauterine bone marrow transplantation.47

Persons with beta-thalassemia major lived a mean of 17 years in 1970, most dying by 30 years of age.48 Recent studies demonstrated mean survival ages of 50 and 57 for patients with beta-thalassemia major and minor, respectively. The increased survival is likely attributable to increasing availability of transfusion and iron chelation therapies, and improved iron overload monitoring.25,49

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Muncie and Campbell.9

Data Sources: This article was based on literature searches in Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, PubMed, and Ovid using the term thalassemia. Search dates: October 2020 to October 2021.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army at large, or the Defense Health Agency.