Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(6):593-601

Related Letter to the Editor: Alcohol Use Disorder Following Metabolic Surgery

Author disclosure: A public database shows that Dr. Harrison has attended an industry-sponsored training course for robotic-assisted surgery; this is considered standard practice and is required to use the surgical platform in bariatric surgery. He has not served as a speaker or consultant for this company. Drs. Banerjee and Schroeder have no relevant financial relationships.

In 2019, approximately 256,000 metabolic surgery procedures were performed in the United States, a 32% increase since 2014. The most common procedures are the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Choice of procedure depends on concurrent medical conditions, patient preference, and expertise of the surgeon. These procedures have a mortality risk of 0.2% to 0.3%. On average, weight loss of 30 to 50 kg (66 to 110 lb), or a 20% to 30% reduction in total body weight, is achieved, although most patients will experience some weight regain three to 10 years after surgery. In patients who have had metabolic surgery, all-cause mortality is reduced by 30% to 45% at two to 15 years postsurgery compared with patients with obesity who did not have surgery. Approximately 70% of surgical patients achieve remission of type 2 diabetes, and over 30% of surgical patients maintain remission at 10 years. [corrected] Other obesity-related conditions are also greatly reduced, and quality of life improves. Postoperatively, patients require standardized nutritional supplementation and surveillance. Persistent changes in diet, such as consuming protein first at every meal, regular physical activity, and ongoing attention to behavior change are critical for the success of the patient after metabolic surgery. Common adverse outcomes include surgical complications, nutritional deficiencies, bone density loss, dumping syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and loose skin. The family physician is well positioned to counsel patients about metabolic surgical options and the risks and benefits of surgery and to provide long-term support and medical management for postsurgery patients.

What Procedures Are Commonly Performed?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

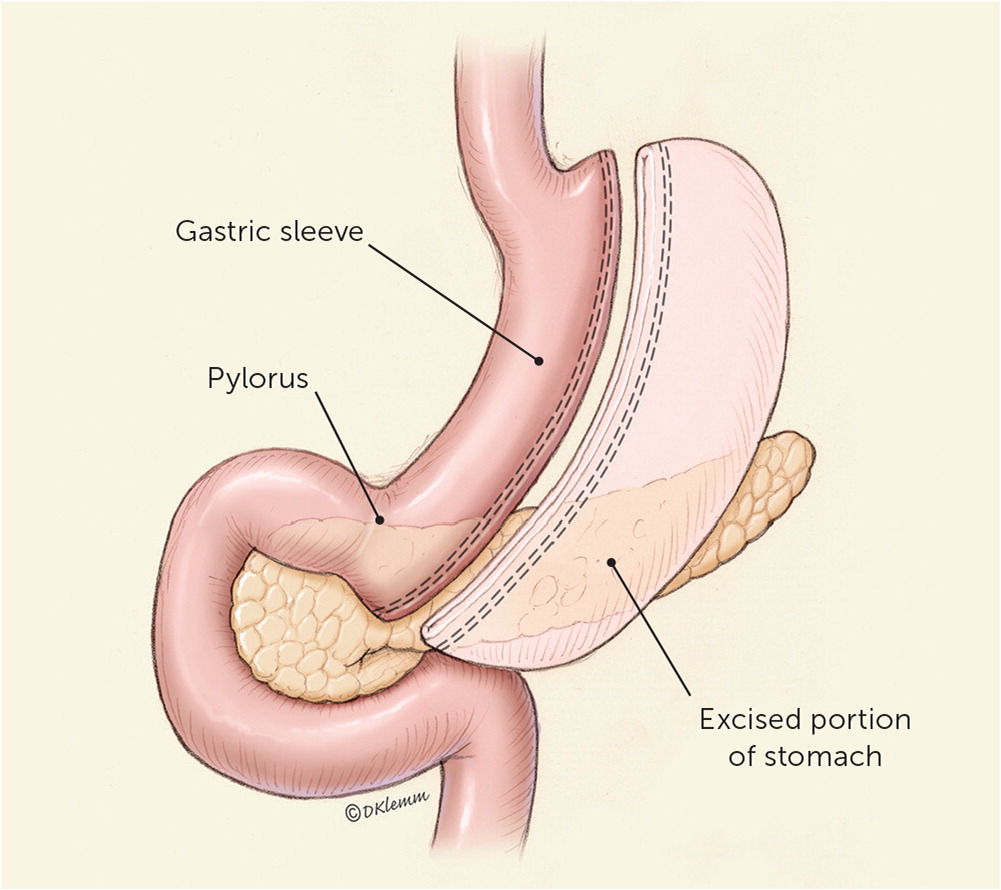

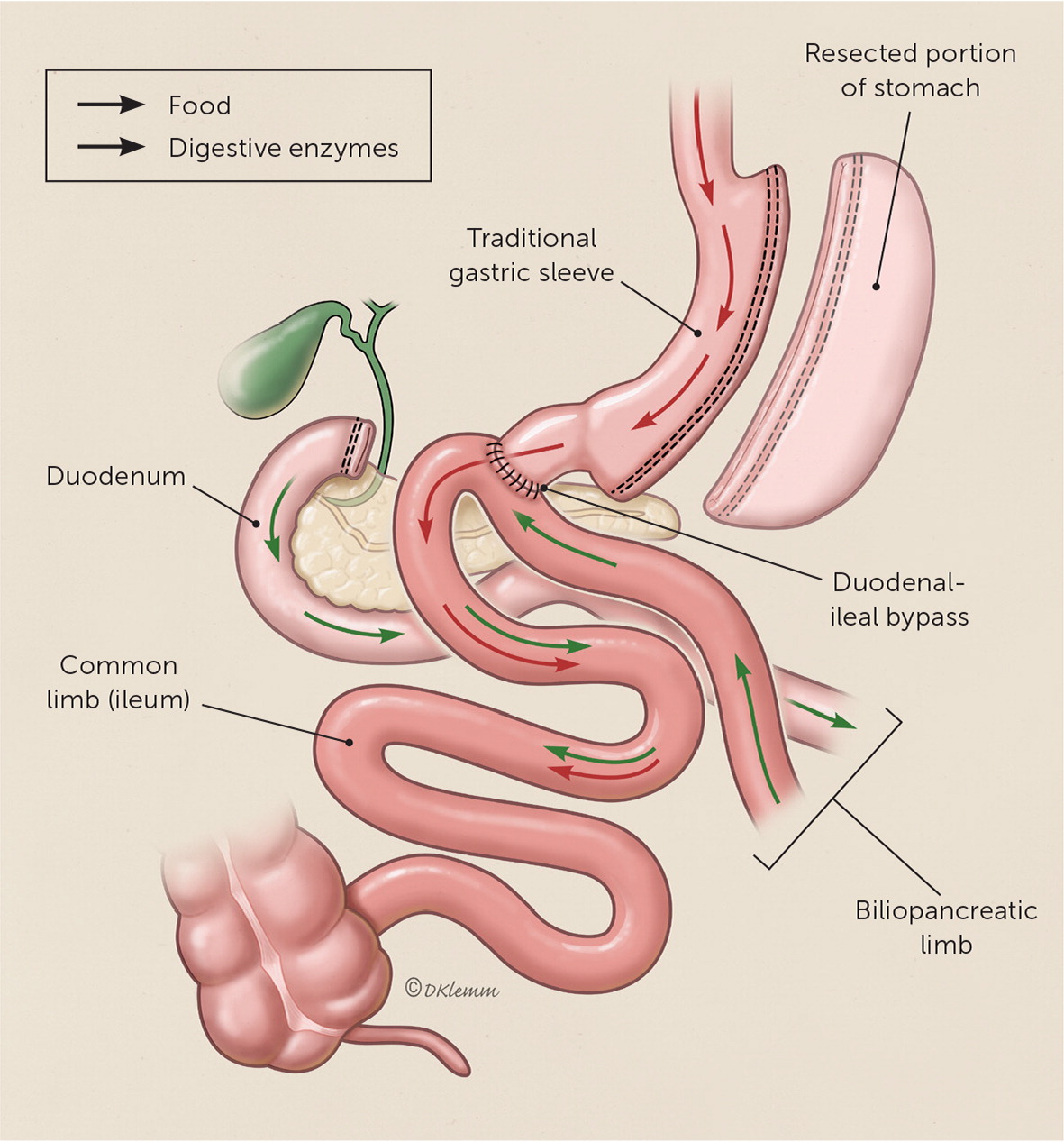

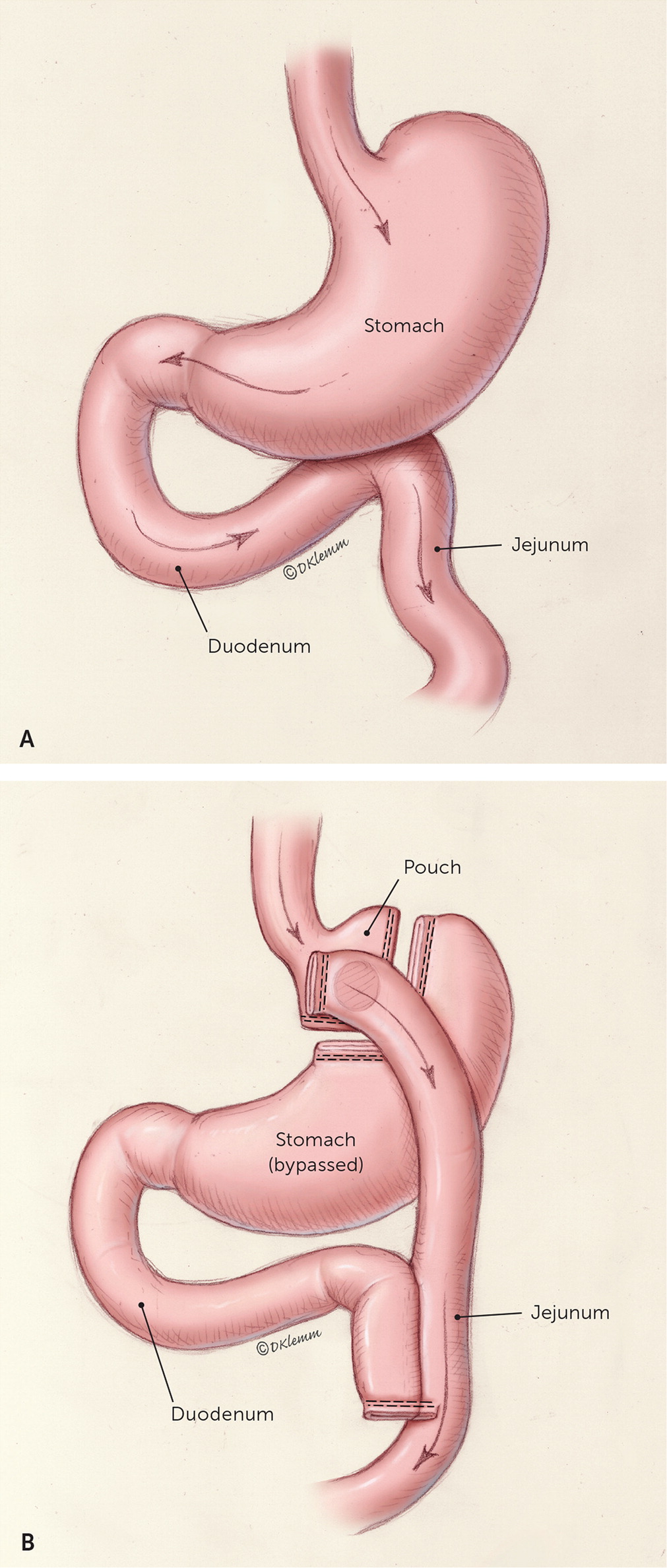

The sleeve gastrectomy procedure resects most of the body and all of the fundus of the stomach, creating a long, narrow, tubular stomach (Figure 18). Single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve was endorsed by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery in 2020 and will likely become more prevalent in the coming years.9 Single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve adds a bypass of the duodenum to traditional sleeve, which can be performed as a single procedure or as a revision to a prior sleeve gastrectomy (Figure 2).

How Does Metabolic Surgery Lead to Weight Loss and Improvement in Type 2 Diabetes?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Who Is Eligible for Metabolic Surgery?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

| Selection criteria |

| Able to adhere to postoperative care plan (e.g., follow-up visits and tests, medical management, use of dietary supplements) |

| Class 1 obesity (BMI of 30 to 34.9 kg per m2) and diabetes mellitus with inadequate glycemic control despite optimal lifestyle and medical therapy |

| Class 2 obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg per m2) and at least 1 severe, obesity-related condition (type 2 diabetes, prediabetes, hypertension, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, obstructive sleep apnea, osteoarthritis of the knee or hip, and urinary stress incontinence; consider for obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, severe venous stasis, impaired mobility due to obesity, and considerably impaired quality of life) |

| Class 3 obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg per m2) |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Cardiopulmonary disease that would make the risk prohibitive |

| Current illicit drug or alcohol use |

| Current tobacco use |

| Lack of comprehension of risks, benefits, expected outcomes, alternatives, and required lifestyle changes |

| Reversible endocrine or other disorders that can cause obesity |

| Uncontrolled severe psychiatric illness |

What Are the Key Components of the Presurgical Evaluation?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

| Recommend |

| Age- and risk-appropriate cancer screening |

| Complete history and physical examination (e.g., assess obesity-related conditions, weight-loss history, commitment to postsurgical lifestyle modifications, exclusions for surgery) |

| Discontinue estrogen medications preoperatively (1 cycle for oral contraceptives, 3 weeks for hormone therapy) to decrease risk of thrombosis |

| Laboratory studies* (e.g., A1C, complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, folic acid, iron, lipid profile, prothrombin time, urinalysis, vitamin B12, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, additional evaluation as indicated) to identify and optimize the most common obesity-related and postoperative conditions |

| Nutrition evaluation |

| Pregnancy counseling† |

| Psychosocial and behavioral evaluations |

| Tobacco cessation counseling for optimal wound healing |

| Additional evaluations to consider |

| Cardiopulmonary (e.g., polysomnography, electrocardiography, additional evaluation if cardiac disease or pulmonary hypertension suspected) |

| Gastrointestinal (Helicobacter pylori screening in high-prevalence areas; gall bladder evaluation, upper endoscopy if clinically indicated) |

| Liver ultrasonography if elevated liver function tests |

| Thiamine level before malabsorptive procedure |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone and testing for syndromic causes of obesity only if clinically indicated |

After Metabolic Surgery, What Should the Patient Do and Expect?

| Supplement | Recommended dosage | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium citrate | 1,200 to 1,500 mg per day | Split doses; monitor for osteoporosis |

| Elemental iron | 45 to 60 mg per day (including multivitamin) | Take iron and calcium supplements at least 2 hours apart |

| Multivitamin with minerals (including iron, folic acid, copper, selenium, thiamine, and zinc) | 2 per day | Liquid or chewable for 3 to 6 months, bariatric vitamin is preferred |

| Vitamin B12 | 1,000 mcg per day | Sublingual, subcutaneous, intramuscular, or oral if adequately absorbed |

| Vitamin D3 | At least 3,000 IU per day | Titrate to 25-hydroxy-vitamin D level > 30 ng per mL (74.88 nmol per L) |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Patients may require repeated adjustments to lipid-lowering, antihypertensive, diabetes, and thyroid medications. 7 Changes in medication absorption, distribution, and metabolism after metabolic surgery are highly variable, and evidence does not support routine changes in medication administration.17 If physicians suspect medication malabsorption or if patients experience difficulty swallowing pills, switching to liquid, soft-gel, crushed tablet, or non-oral medications should be considered.7,17 Patients should avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because of increased risk of anastomotic ulcerations.7

The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and the American College of Surgeons mandate that surgical centers follow patients for the first year after surgery and attempt to follow patients annually for life.18 However, patients may request primary care management. Quarterly assessment of nutritional status and supplementation needs, food intolerances, and symptoms should occur for the first postsurgical year (Table 4).7 Vitamin supplementation is required throughout the patient's lifetime, and annual metabolic and nutritional monitoring is recommended (Table 3).7

| Adjust postoperative medications as needed |

| Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Avoid pregnancy for 12 to 24 months |

| Consider gout and gallstone prophylaxis in appropriate patients |

| Measure bone density with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry at 2 years postsurgery |

| Monitor progress with weight loss and adherence to dietary, behavioral, and physical activity recommendations |

| Obtain quarterly laboratory studies for first year (A1C, complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, iron, vitamin B12) |

| Perform annual laboratory studies (complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, copper and ceruloplasmin iron studies, intact parathyroid hormone level, lipid profile, thiamine, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin A, vitamin B12, zinc, 25-hydroxyvitamin D)* |

Slow progression of diet from clear liquids to regular food is necessary over the first four to six weeks postoperatively.7 After surgery, each meal should begin with protein to ensure adequate intake (at least 60 g [2.14 oz] per day) to minimize the loss of lean body mass.7 Food intolerances are patient specific, but very dry foods, breads, and fibrous vegetables are often problematic. Fluids should be avoided for 15 to 30 minutes before, during, and after meals because food mixed with fluid will pass easily through the stomach, diminishing the sensation of fullness. Carbonated beverages should be avoided because of the added gas.

What Are the Long-Term Benefits of Metabolic Surgery?

Although most patients who have metabolic surgery will not achieve a BMI of less than 25 kg per m2, patients generally experience significant weight loss.20–24 These patients have an average life expectancy 2.4 to three years longer than similar nonsurgical patients.24 Outcomes of metabolic surgery are summarized in Table 5.7,20–44

| Outcome | Overall | Sleeve gastrectomy | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excess body weight lost postsurgery | Average* | ||

| 1 to 2 years | 60% to 70% | 33% to 85% | 48% to 85% |

| 5 years | 50% to 60% | 46% to 66% | 53% to 77% |

| 10 years | 50% | ||

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension | 90% resolution of headache; 100% resolution of papilledema | ||

| Mortality | |||

| < 90 days | 0.2% to 0.3% | ||

| 2 to 15 years | 30% to 45% lower than nonsurgical controls | ||

| > 20 years | 23% lower than nonsurgical controls | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Decrease in Apnea-Hypopnea Index by 29 per hour | ||

| Remission of hyperlipidemia | 60% to 82% | ||

| Remission of hypertension | 17% to 49% | ||

| Remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus | |||

| 1 to 2 years | 72% to 80% | 56% to 68% | 56% to 84% |

| 5 years | 50% to 70% | ||

| 10 to 15 years | 30% to 38% | ||

| Resolution of urinary stress incontinence | 47% | ||

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Over the first three years after surgery, patients lose 30 to 50 kg (66 to 110 lb) on average, corresponding to a BMI decrease of 11 to 17 kg per m2 and a 60% to 70% reduction in excess body weight (a 20% to 30% reduction in total body weight).20–23,25,26 Most patients will experience some degree of weight regain between three and 10 years after surgery and stabilize at an average loss of 17% to 30% of excess body weight.24,27 Roux-en-Y gastric bypass generally leads to greater weight loss than sleeve gastrectomy during the first two postsurgical years, but it is unclear whether a significant long-term difference occurs.23 Limited evidence suggests that single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve is associated with greater weight loss and improved weight maintenance compared with other procedures.45,46

Metabolic surgery results in significant improvement in obesity-related conditions. Approximately 70% of surgical patients achieve remission of type 2 diabetes, and about 38% of surgical patients maintain remission at 10 years.27,28 Even without remission, approximately 90% of surgical patients experience improvement in diabetes control and have decreased risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications.29–31 No difference has been found between procedures in the rate of remission or improved control of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, or obstructive sleep apnea.32

Patients who have undergone metabolic surgery are less likely to develop new-onset type 2 diabetes; hypertension; obstructive sleep apnea; dyslipidemia; ischemic heart disease; cardiac failure; melanoma; or breast, colon, endometrial, and pancreatic cancers. 33,47,48 After the initial postoperative period, mortality rates among patients who have had metabolic surgery are significantly lower than nonsurgical control patients.20,24,25,33–35,49 Mortality rates remain lower 20 years postsurgery.24

What Adverse Outcomes Are Common After Metabolic Surgery?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Cold intolerance, hair loss, and fatigue are common during the first year because of rapid weight loss, but these adverse effects diminish as weight loss stabilizes.

Malabsorptive procedures, including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve, are associated with a higher risk of nutritional deficiencies than other procedures, particularly for patients who do not follow vitamin supplementation recommendations. Anemia affects 17% of patients who have sleeve gastrectomy and 45% to 50% of patients who have Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; anemia can be associated with deficiencies of iron, vitamin B12, folate, copper, selenium, and zinc.52 Notably, patients who have sleeve gastrectomy are at risk of vitamin B12 deficiency due to a decrease in intrinsic factor–producing parietal cells.52 Deficiencies of vitamins B1 (thiamine), A, D, E, K, and protein may also occur.52

Bone density loss affects 8% to 13% of patients who have metabolic surgery.52 This is likely multifactorial from calcium deficiency, vitamin D deficiency, and adaptive bone unloading from weight loss. Initial treatment involves correction of vitamin D and calcium deficiencies.53 If pharmacotherapy is indicated after correcting deficiencies, parenteral therapy is preferred because oral bisphosphonates increase the risk of anastomotic ulceration.53

Symptoms of dumping syndrome occur in up to 40% of patients after metabolic surgery.54 Early dumping syndrome is caused by rapid passage of nutrients into the small bowel, resulting in intestinal hormonal release and fluid shift. Symptoms occur within one hour of eating and include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloating, nausea, flushing, palpitations, sweating, tachycardia, hypotension, and syncope.54 Late dumping syndrome is caused by rapid absorption of carbohydrates, causing exaggerated insulin secretion. This results in hypoglycemia one to three hours after eating.54 Treatment includes eating small, frequent meals; avoiding fluids with meals; and avoiding rapidly absorbed sugars.54 If this is not effective, acarbose (Precose) may be added to slow carbohydrate digestion.54 Other treatment options include somatostatin analogues and surgical revisions.54

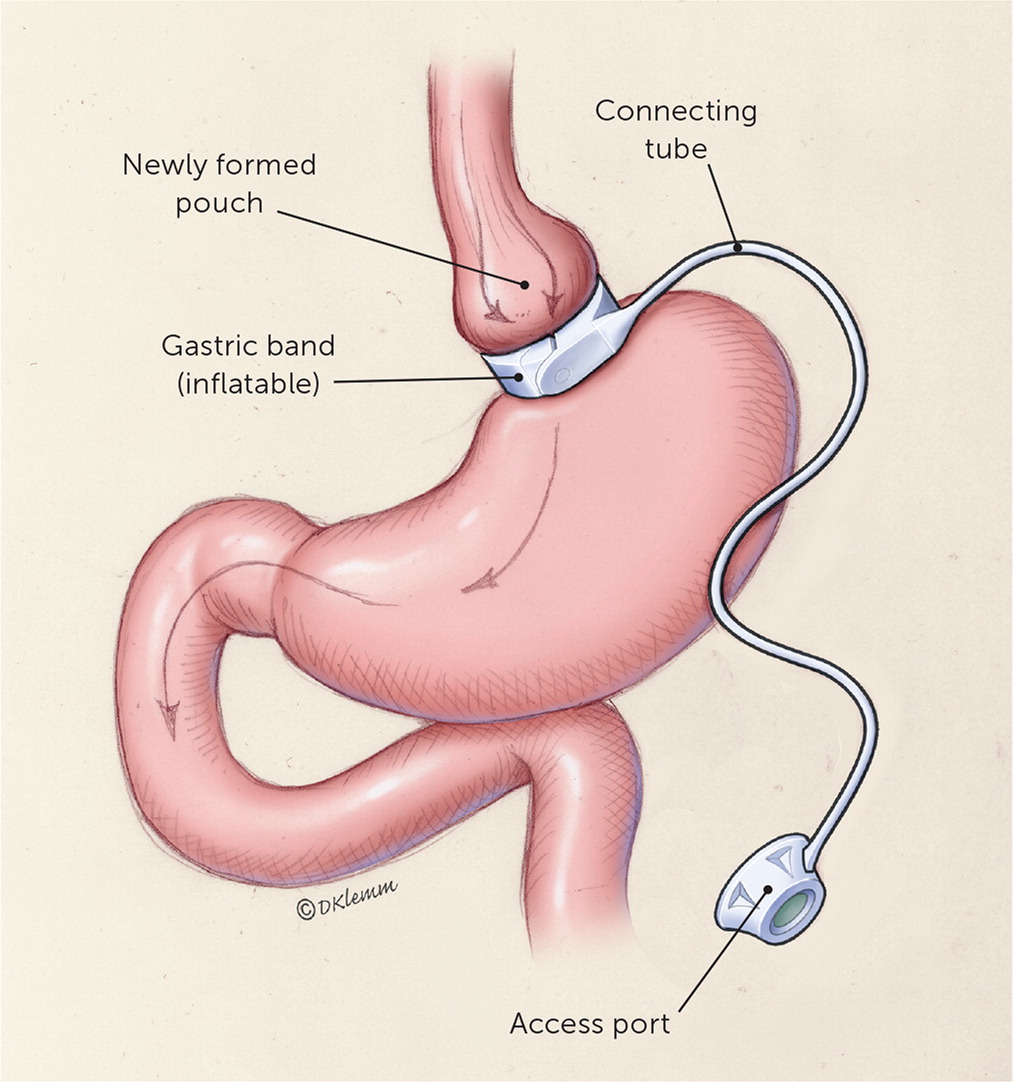

GERD may improve with weight loss but can worsen with decreased stomach size. Compared with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy is less likely to improve GERD32,55 and is five times more likely to result in new-onset GERD postoperatively.55 Patients with an adjustable gastric band also commonly present with GERD symptoms. The first therapeutic step is to loosen the band. If no improvement in GERD symptoms occurs, the band may need to be removed, with or without a revision to another metabolic procedure.

Loose skin is a result of significant weight loss and affects approximately 84% of patients who have had metabolic surgery.56 Complications include irritation, fungal infections, difficulty finding clothing, patient perception of unattractiveness, and discomfort during exercise.56 About 20% of patients undergo body-contouring surgery.57 Approximately 2% of patients regret having metabolic surgery.56

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Schroeder, et al.,8 and Schroeder, et al.60

Data Sources: The following resources were reviewed: the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. References from key articles were searched, as were references from Essential Evidence Plus. In addition, a PubMed search was performed using key words obesity, metabolic surgery, bariatric surgery, and diabetes. Search dates: February 10, 2021; June 25, 2021; and December 13, 2021.