Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(3):260-268

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

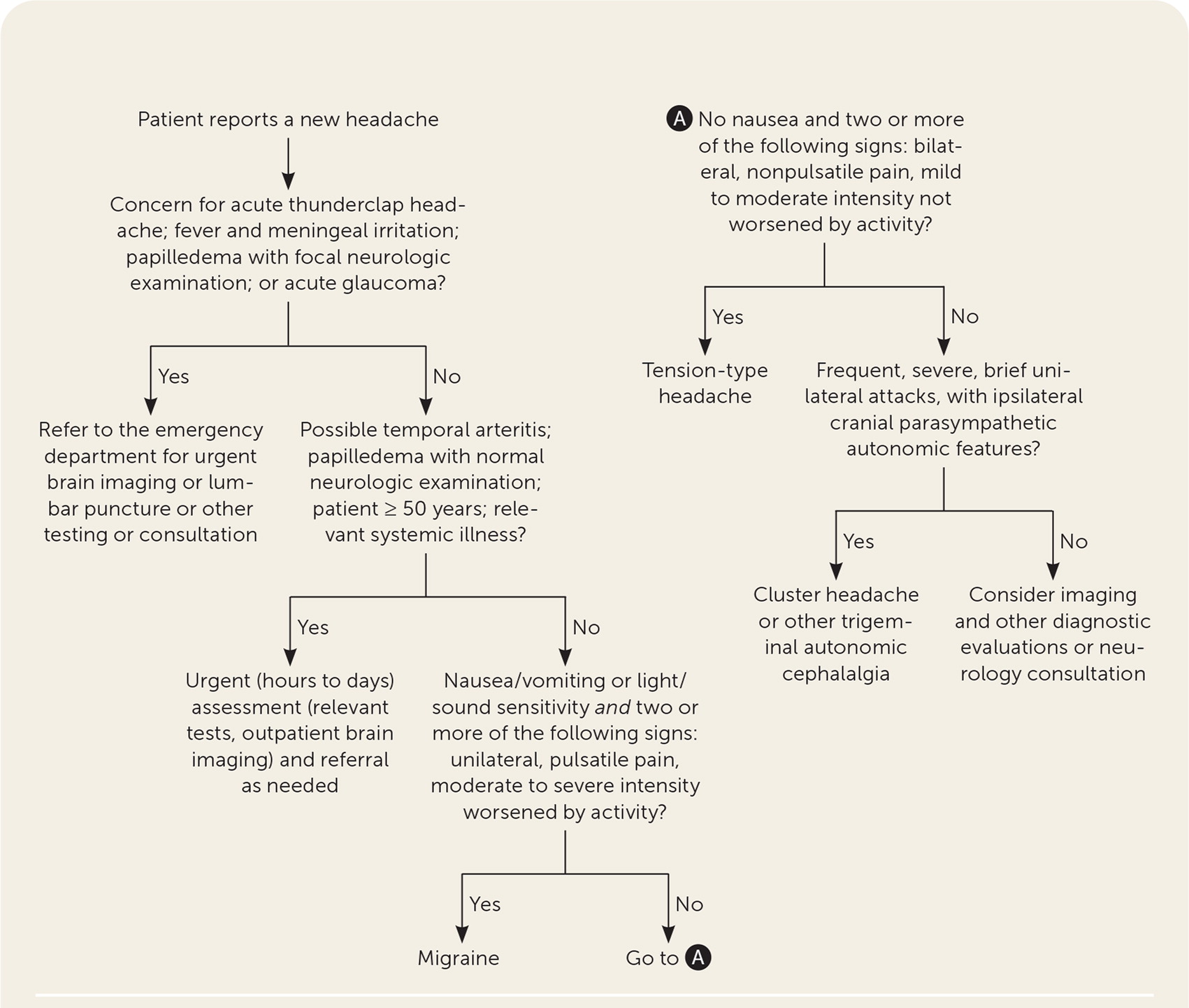

A detailed history and physical examination can distinguish between key features of a benign primary headache and concerning symptoms that warrant further evaluation for a secondary headache. Most headaches that are diagnosed in the primary care setting are benign. Among primary headache disorders, tension-type headache is the most common, although a migraine headache is more debilitating and likely to present in the primary care setting. Signs such as predictable timing, sensitivity to smells or sounds, family history of migraine, recurrent sinus headache, or recurrent severe headaches with a normal neurologic examination could indicate migraine headache. Evaluating acute headaches using a systematic framework such as the SNNOOP10 mnemonic can help detect life-threatening secondary causes of headaches. Red flag signs or symptoms such as acute thunderclap headache, fever, meningeal irritation on physical examination, papilledema with focal neurologic signs, impaired consciousness, and concern for acute glaucoma warrant immediate evaluation. For emergent evaluations, noncontrast computed tomography of the head is recommended to exclude acute intracranial hemorrhage or mass effect. A lumbar puncture is also needed to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage if the scan result is normal. For less urgent cases, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain is preferred for evaluating headaches with concerning features. Primary headache disorders without red flags or abnormal examination findings do not need neuroimaging.

A detailed history and physical examination can distinguish between key features of benign primary headaches (e.g., tension-type, migraine, trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia) and concerning symptoms that warrant further evaluation for a secondary headache (e.g., subarachnoid hemorrhage, giant cell arteritis). Most headaches assessed in primary care are benign. It is important to diagnose a patient's headache accurately and identify patients for whom an additional but less urgent evaluation is necessary 1–4 (Figure 1; Table 11–3 and Table 21,2,4).

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not perform imaging for uncomplicated headache. | American College of Radiology |

| Do not perform neuroimaging studies in patients with stable headaches that meet criteria for migraine. | American Headache Society |

| Do not perform computed tomography imaging for headache when magnetic resonance imaging is available, except in emergency settings. | American Headache Society |

| Do not perform electroencephalography for headaches. | American Academy of Neurology |

| History components | Example questions | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Associated symptoms | What are your associated symptoms (e.g., aura, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, autonomic symptoms, neck pain, fever)? | Noting an aura before a headache suggests migraine; neck pain and fever are potential red flags |

| Character | What are the headache qualities (e.g., pulsatile, throbbing, pressure-like)? Has the headache changed in intensity or frequency? | Changes in quality, frequency, or intensity should merit further evaluation |

| Comorbid conditions | Are there other medical problems that may be related to headache (e.g., mood symptoms, hypertension, pregnancy, history of heart disease or stroke, immunosuppression)? | Comorbidities may need to be factored into the diagnosis and management plan |

| Duration | How long does each attack last (e.g., seconds, minutes, hours, days)? | Headaches lasting only seconds are unlikely to be tension-type headache or migraine |

| Frequency | How often do the attacks occur (e.g., days per month)? How many days per week or month are you headache-free? | Helps distinguish between acute and chronic headache |

| Location | Where is the pain? Is the headache unilateral or bilateral? Does it radiate? To where? | Cluster headache and migraine tend to be unilateral |

| Medications | What medications have you taken for the headache? How often and at what dose? | Medication overuse can lead to headache |

| Onset | At what age did the headaches begin? Was the onset sudden or gradual? | Sudden onset and onset at 50 years and older are more concerning |

| Precipitating factors | Are there symptoms before the headache starts (e.g., aura, jaw pain), activities (e.g., trauma, cough, exertion, sexual intercourse, neck movement), or ingestions (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, caffeine) that trigger the headache? Are headaches predictable in timing (e.g., before menstruation or ovulation)? | Migraine may have predictable triggers |

| Severity | How quickly does the headache peak in intensity? How bad is the pain on a scale of 1 to 10? How does the headache affect your daily functioning? | Tension-type headache tends to develop insidiously; migraine is more sudden |

| Examination component | Features | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Vital signs | Blood pressure, temperature, pulse, respirations | Fever is a potential red flag |

| Focused neurologic examination | Mental status, Glasgow Coma Scale score Cranial nerve evaluation including funduscopy Strength and sensory tests Deep tendon reflexes Coordination and gait | Any abnormal neurologic examination finding is a red flag |

| Concern for temporomandibular joint disorder | Assessment of jaw opening Palpation of mastication muscles (masseter, temporalis, pterygoids) | Decreased range of motion or tenderness with palpation is concerning |

| Concern for central nervous system infection | Neck examination to assess for meningeal irritation | Note that classic features such as Kernig sign and Brudzinski sign are of limited value |

Headache Classification

The International Classification of Headache Disorders publishes an extensive classification system5; however, a simpler approach is to categorize headaches into primary and secondary disorders. Primary headache disorders are benign and do not have a separate underlying etiology that requires further evaluation. Some secondary headache disorders can be life-threatening and are caused by an underlying process such as medication overuse, infection, head trauma, or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Primary Headache Disorders

| Headache features | Tension-type headache | Migraine headache | Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias and cluster headache |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No nausea and 2 or more of the following: Bilateral location Nonpulsatile pain (usually pressing, tightening) Mild to moderate intensity Not exacerbated by activity | At least 1 of the following: Nausea or vomiting Photophobia or phonophobia And 2 or more of the following: Unilateral location Pulsatile pain Moderate to severe intensity Exacerbated with activity | Unilateral (usually recurs on the same side) Severe orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain And 1 or more of the following ipsilateral features: Conjunctival erythema or lacrimation Rhinorrhea Forehead or facial diaphoresis Upper eyelid ptosis or constricted pupil |

| Other symptoms | With or without pericranial tenderness | With or without aura | Restlessness or agitation |

| Duration | 30 minutes to 7 days | 4 to 72 hours | 15 minutes to < 3 hours |

| Frequency | At least 10 attacks in a lifetime | At least 5 attacks in a lifetime | At least 5 attacks in a lifetime Each cluster attack occurs from every other day to 8 per day Cluster attacks cycle between remission periods of a few months |

| Chronic type diagnosis requirement | Symptoms ≥ 15 days per month for > 3 months | Symptoms ≥ 15 days per month for > 3 months | Remission interval < 3 months, or attacks occur for ≥ 1 year without remission |

TENSION-TYPE HEADACHE

Tension-type headache (TTH) is the most common primary headache disorder but may not be addressed in the clinical setting because it is not typically disabling unless chronic. One study estimated a lifetime prevalence as high as 78%, and another found that in any year, 38% of adults in the United States have TTH disorder.9,10 Prevalence peaks between 30 and 39 years of age, and TTH occurs slightly more often in women.10

Classically, TTH causes a bilateral, nonpulsatile pain attack of mild to moderate intensity. TTH subtypes are stratified based on frequency: infrequent episodic (less than one day per month), frequent episodic (one to 14 days per month), and chronic (15 or more days per month).5 The diagnosis of episodic TTH is more common than chronic. Patients with chronic TTH have a greater burden of disease. One study reported a threefold increase in average days missed from work for patients diagnosed with chronic vs. episodic TTH (27 vs. nine days per year).10

MIGRAINE HEADACHE

Migraine headache has a lifetime prevalence of 16% and a one-year prevalence of 12%.11,12 Migraine headache is more common in women (one-year prevalence is 17% of women vs. 5.6% of men).12 Migraine prevalence peaks between 20 and 50 years of age. Although an acute headache is the fourth most common reason for an emergency department visit, nearly 53% of visits for migraine headaches in the United States occur in primary care settings.13

Although migraine headache is less common than TTH, it is more debilitating. One study concluded that migraine headache significantly reduced quality of life to a similar degree as congestive heart failure, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus.14 The annual direct and indirect cost of health care resources and lost productivity was estimated to be $36 billion in 2016, likely driven by the high prevalence of migraine headache during peak employment years.15

Migraine headache usually causes unilateral, pulsatile pain attacks of moderate to severe intensity.5 It is often accompanied by nausea, sensitivity to light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia), and is exacerbated with activity. Other indicators of migraine headache include family history of migraine, childhood precursors (e.g., motion sickness, episodic vertigo), predictable timing (e.g., around menstruation), or intolerance to smells (i.e., osmophobia). A migraine may present with or without aura. An aura is a reversible visual (e.g., flickering lights or spots), sensory (e.g., pins and needles, numbness, smell, sound), or speech disturbance (e.g., dysphasia, dysarthria) that precedes the headache and can last five to 60 minutes. Visual aura is the most common type of aura. Visual changes associated with migraine headache tend to be gradual and in a shimmering or zigzagging pattern as opposed to visual changes associated with a transient ischemic attack, which is a more abrupt visual loss without shimmering lights or a zigzag pattern.

The POUND mnemonic (pulsating, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral, nausea, disabling) and the ID Migraine rule are clinical decision rules that can help diagnose migraine in primary care16–18 (Table 416–19). The POUND mnemonic uses five clinical features that were identified as the best independent predictors of migraine.19 Headaches with at least four POUND clinical features are most likely to be a migraine.16 The three-item ID Migraine rule asks about the presence of light sensitivity, nausea or vomiting, and activity-limiting headache during the past three months to determine the likelihood of a migraine diagnosis.18 Patients who experienced two or more items are considered to have a positive screening result.18

| Clinical deci sion rule | Clinical features of headache (1 point added for each affirmative response) | Number of positive findings in patient | Likelihood ratio | Probability of migraine diagnosis* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POUND mnemonic (pulsating, duration of 4 to 72 hours, unilateral, nausea, disabling) | 1. Pulsatile quality 2. Duration of 4 to 72 hours 3. Unilateral location 4. Nausea or vomiting 5. Disabling intensity | 0 to 2 3 4 to 5 | 0.41 3.5 24 | 17% 64% 92% |

| ID Migraine | 1. Light sensitivity 2. Nausea or vomiting 3. Disabling intensity | 0 to 1 2 to 3 | 0.25 3.2 | 11% 62% |

Migraine headache is classically underdiagnosed. Patients for whom a diagnosis of migraine should be considered include those with recurring sinus headaches or recurrent severe headaches with a normal neurologic examination.1

TRIGEMINAL AUTONOMIC CEPHALALGIAS

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias are uncommon. Patients with this type of headache may benefit from a consultation with and comanagement by a neurologist because of their relatively infrequent occurrence. Subtypes of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias include cluster headache, paroxysmal hemicrania, hemicrania continua, and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks.5 These headaches present with strictly unilateral pain with ipsilateral cranial parasympathetic autonomic features (e.g., lacrimation, rhinorrhea, diaphoresis). Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias subtypes can be differentiated by their frequency, duration, and treatment response.8

Cluster headache is the most well-studied and common type of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Cluster headache is relatively rare compared with migraine or TTH, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 0.1%.20 Historically, men are affected three times more than women; however, this predisposition may be diminishing.7,21

Cluster headache is described as a series of severe unilateral pain attacks to the orbital, supraorbital, or temporal regions. Cluster attacks are often associated with restlessness or ipsilateral cranial autonomic symptoms. The attacks are brief but frequent, typically lasting less than three hours but recurring up to eight times per day. A series of cluster attacks may last weeks or months, followed by a period of remission for at least three months.

Secondary Headaches

Secondary headaches may be life-threatening, and patients with secondary headaches rarely present to primary care clinics. One study of neuroimaging on all patients presenting with headache to an outpatient neurology clinic noted only 1% with significant intracranial abnormality.22 Presumably, patients presenting to primary care clinics for initial evaluation of their acute headaches have a much lower prevalence of significant intracranial abnormalities16; therefore, it is helpful to use a systematic framework combined with the SNNOOP10 mnemonic (Table 52,4,16,23,24) to avoid missing a life-threatening diagnosis among the more common, and benign, primary headaches.23–25

| Signs or symptoms | Differential diagnosis | Possible workup |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic symptoms (e.g., fever,* hypertension) | Meningitis, encephalitis, carcinoid syndrome, Lyme disease, pheochromocytoma, collagen vascular disease | Blood tests, lumbar puncture, neuroimaging, skin biopsy |

| Neoplasm history | Brain metastasis, intracranial neoplasm | Neuroimaging |

| Neurologic deficit | Central nervous system infection, vascular malformation, stroke, intracranial mass lesion | Blood tests, neuroimaging, neurology consultation |

| Onset is sudden/abrupt (thunderclap headache*) | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, other cranial or cervical vascular disorder, posterior fossa mass lesion | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture |

| Older age (> 50 years) | Giant cell arteritis, cranial or cervical vascular disorder, neoplasm | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, neuroimaging |

| Pattern change or recent onset | Mass lesion, intracranial disorder, medication overuse or use disorder | Neuroimaging, medication review, urine drug screen |

| Positional | Intracranial hypertension or hypotension (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid leak) | Neuroimaging |

| Precipitated by sneezing, coughing, or exercise | Posterior fossa lesion (e.g., Chiari malformation), subarachnoid hemorrhage | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture |

| Progressive or atypical presentation | Mass lesion, intracranial disorder | Neuroimaging |

| Papilledema* | Intracranial hypertension, mass lesion, nonvascular intracranial disorder | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture, ophthalmology consultation |

| Pregnancy or postpartum | Cranial or cervical vascular disorder, hypertension related (e.g., preeclampsia), cerebral sinus thrombosis, postdural puncture, hypothyroidism, anemia, diabetes mellitus | Blood tests, neuroimaging |

| Painful eye with autonomic features | Ophthalmic disorder, pathology of posterior fossa, pituitary, or cavernous sinus, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome | Neuroimaging, ophthalmology consultation |

| Posttraumatic onset | Acute or chronic posttraumatic headache, subdural hematoma | Neuroimaging, including brain, skull, and possibly cervical spine |

| Pathology of immune system (e.g., HIV) | Opportunistic infection (e.g., meningitis, brain abscess, metastasis) | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture |

| Painkiller overuse or new medication | Medication overuse headache, drug incompatibility | Medication review and reconciliation |

Certain positive results on the SNNOOP10 mnemonic warrant an emergent evaluation; others may need to be addressed urgently, within hours or days.1 Immediate evaluation is necessary for acute thunderclap headache because of its high pretest probability (greater than 40%) for serious intracranial pathology such as subarachnoid hemorrhage.16 There is no consensus definition of sudden or abrupt onset, but clinicians should quickly evaluate a patient with a headache that peaks within seconds to minutes.4,23

Headache with fever is sensitive, but not specific for a neurologic infection.23 Although fever alone may not warrant a prompt evaluation, signs of meningeal irritation on physical examination (classic signs such as Kernig and Brudzinski are of limited value) in the same patient increase the possibility for a serious infection and should be considered an emergency.1 Papilledema with focal neurologic signs or impaired consciousness, and concern for acute glaucoma (e.g., eye pain or injection, blurred vision, halos around lights) are two other presentations that require immediate evaluation and treatment.1

Some patients with atypical or concerning headache patterns may warrant nonemergent neuroimaging. One pooled analysis identified the history and physical examination findings most associated with significant intracranial lesions.16 These findings included cluster-type headache, abnormal neurologic examination, a headache that does not meet any primary headache criteria, and headache associated with aura, exertion, or Valsalva maneuver.16 Such findings during an office visit should cause consideration for further diagnostic evaluation.

Primary headache onset after 50 years of age is uncommon, and onset after 65 years of age carries a high risk of a serious secondary etiology.23,26 In patients older than 50 years, giant cell arteritis must be considered. The presence of fever, scalp tenderness overlying the temple, jaw claudication (i.e., pain or facial fatigue with chewing), or symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica (i.e., pain, stiffness, decreased range of motion in shoulder muscles) could suggest giant cell arteritis. These patients need an urgent laboratory evaluation because of the potential for ophthalmic and neurologic complications.27

Although anxiety-provoking for patients, the risk of a brain tumor in a patient with a headache without a previous history of any neoplasm is less than 0.1%. Lung cancer, breast cancer, and malignant melanoma have the highest risk of brain metastasis.23

Additional Diagnostic Evaluation

Patients with stable primary headache disorders do not typically need neuroimaging.1,27–30 One meta-analysis estimated a 0.2% prevalence of a significant intracranial abnormality among patients with migraine headache who had a normal neurologic examination.31 A headache accompanied by an abnormal neurologic examination likely suggests an underlying etiology.27 Neuroimaging and an additional evaluation may be necessary to exclude life-threatening causes of headaches when red flags are present (Table 52,4,16,23,24).

For emergent evaluations of headache, non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the head is sensitive enough to exclude a new intracranial hemorrhage or mass effect.28,32 Patients presenting with acute thunderclap headache should have a CT scan performed within 12 hours of onset.27 A lumbar puncture must follow a reassuring CT scan to sufficiently exclude subarachnoid hemorrhage.3,27

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast is the preferred method for evaluating headaches with other concerning features. Brain MRI is useful when the presenting headache is consistent with trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (to exclude secondary causes)33 or precipitated by cough (to exclude posterior fossa lesion).34 Brain MRI is the preferred study to identify intracranial mass lesions, pathologies involving vascular disease, the posterior fossa, or cervicomedullary lesions.29,32 Although it can be considered during the diagnostic evaluation of a new-onset seizure disorder, electroencephalography is not useful for headache evaluation except in the evaluation of atypical aura with migraine.35

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Hainer and Matheson4 and Clinch.2

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term headache, and was filtered by clinical prediction guides and diagnosis. Also searched were the ACCESSSS database, ECRI Guidelines Trust, Cochrane library database, DynaMed, and Essential Evidence Plus. Note that this search and review did not include cranial neuropathies. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Search dates: July 30, 2021, and June 10, 2022.