Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(4):427-438

Patient information: See related handout on making healthier nutritional food choices, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

About 60% of adults in the United States have one or more diet-related chronic diagnoses, including cancer, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. It is imperative to address nutrition health in the clinical setting to decrease diet-related morbidity and mortality. Family physicians can use validated nutrition questionnaires, nutrition-tracking tools, and smartphone applications to obtain a nutrition history, implement brief intervention plans, and identify patients who warrant referral for interdisciplinary nutrition care. The validated Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants–Shortened Version, v.2 (REAP-S v.2) can be quickly used to initiate nutrition history taking. Patient responses to the REAP-S v.2 can guide physicians to an individualized nutrition history focused in the four areas of nutrition: insight and motivation, dietary intake pattern, metabolic demands and comorbid conditions, and consideration of other supplement or substance use. Family physicians should refer to the U.S. Department of Agriculture 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans when assessing patient nutrient intake quality and pattern; however, it is also essential to assess nutrition health within the context of an individual patient. It is important to maintain a basic understanding of popular diet patterns, although diet pattern adherence is a better predictor of successful weight loss than diet type. Using various counseling and goal-setting techniques, physicians can partner with patients to identify and develop a realistic goal for nutrition intervention.

Nutrition is a well-recognized and vital component of medical treatment, health promotion, and disease prevention.1 After tobacco use, poor nutrition and inadequate physical activity are the most significant modifiable risk factors impacting mortality in the United States.2 About 60% of U.S. adults have one or more diet-related chronic diagnoses, including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and obesity.3 Because patients with normal weight can still be at risk of diet-related chronic diagnoses, family physicians should obtain nutrition history for all patients, regardless of body mass index.4 Nutrition history taking allows family physicians to understand a patient's personal nutrition knowledge, choices, habits, goals, barriers, and motivations. Together, the patient and physician can use the information to implement specific and realistic nutrition health goals that align with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| The Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants–Shortened Version, v.2 (REAP-S v.2) can be used to assess nutrient intake in ambulatory patients with omnivorous, vegetarian, and vegan diet patterns.5 | C | Cross-sectional study of disease-oriented evidence |

| Physicians should ask about a patient's adherence to diet patterns because adherence is more closely associated with weight loss than the diet pattern itself.16,18,20,23 | B | Clinical review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials looking at weight loss and disease-oriented outcomes |

| Patients with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be offered or referred to behavioral counseling, including nutrition counseling.30 | B | Consensus guideline from U.S. Preventive Services Task Force |

| Physicians should routinely screen athletes for eating disorders.39 | C | Expert opinion; American Medical Society for Sports Medicine Position Statement–Executive Summary |

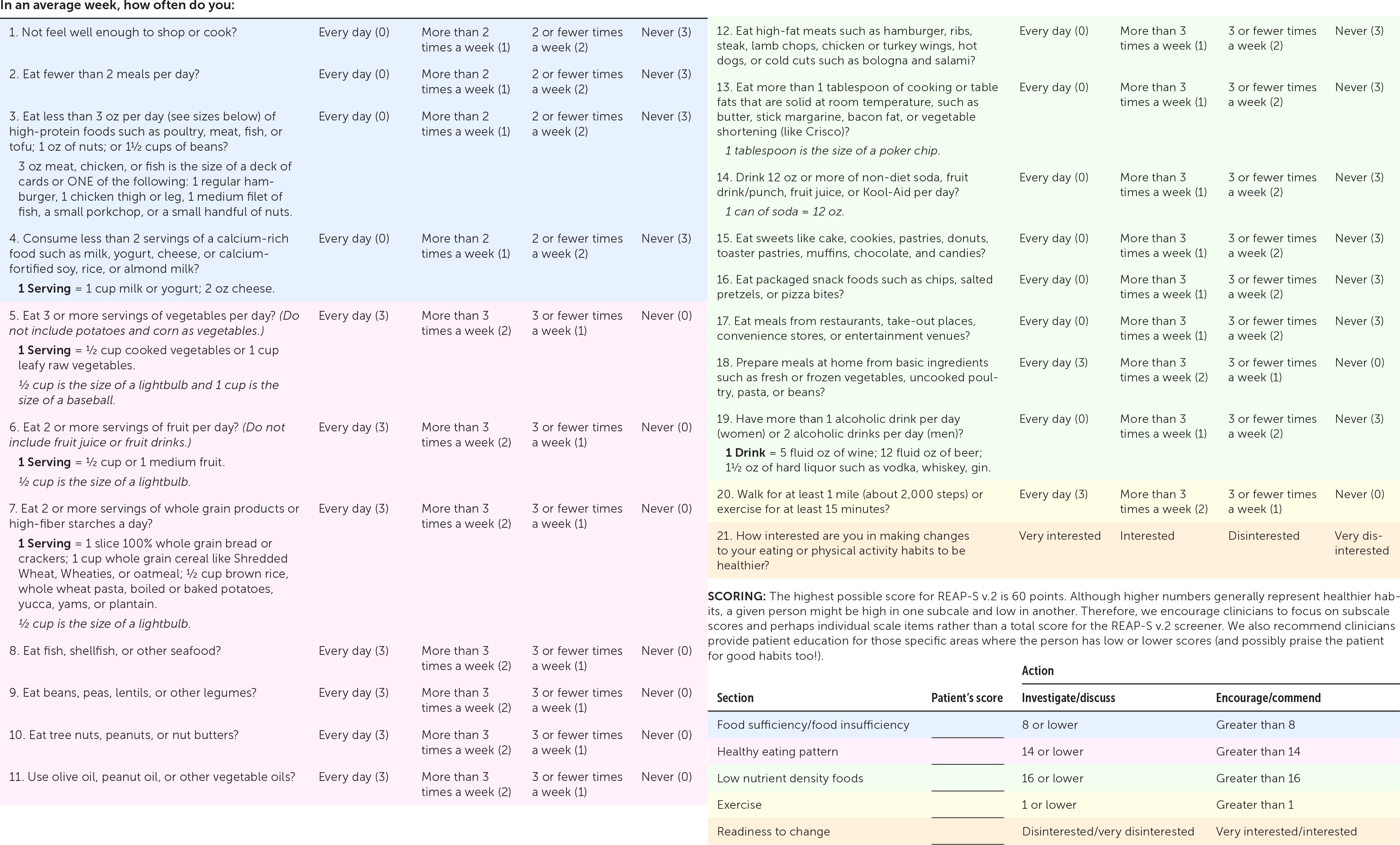

Among the available brief nutrition and diet screening tools, the Rapid Eating Assessment for Participants–Shortened Version, v.2 (REAP-S v.2) is validated for brief dietary assessment in ambulatory patients compared with three-day dietary recall (Figure 1; printable PDF of Figure 1).5 The original REAP-S (2004) was designed to be completed by a patient before their ambulatory visit, and is validated in patients with omnivorous, vegetarian, and vegan diet patterns compared with dietary recall and measured serum nutrition biomarkers.6–8 The 21-question REAP-S v.2 was updated for improved administration, scoring assessment, and alignment with the USDA 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.5 Responses to the REAP-S v.2 can be scored quickly within the areas of dietary adequacy, diet pattern, intake of discretionary calories, exercise habits, and motivation for nutrition change.5 The patient's responses to the REAP-S v.2 should provide an immediate assessment of general nutrition health—lower scores suggest poorer nutrition practices, and higher scores suggest healthier nutrition practices—and create context for family physicians as they further elicit a complete nutrition history using the framework proposed in this article.5 To build a shared understanding of the patient's nutrition health, physicians should gather an individualized nutrition history by focusing on four key components: nutrition insight and motivation, dietary intake pattern, metabolic demands and comorbid conditions, and consideration of other supplement or substance use.

Framework for Nutrition History Taking

1. Nutrition insight and motivation: how would you rate your current nutrition health, and what motivations or barriers to nutrition change do you anticipate?

Regardless of whether a patient reports low or high motivation for nutrition change on the REAP-S v.2, a greater understanding of their mental model regarding nutrition and the importance of improving their nutrition health can shape the remainder of the nutrition history taking, as well as any future intervention. Physicians should ask about social and economic barriers to healthy nutrition, including lack of access to fresh foods based on availability or price, limited time to plan or prepare meals cooked at home, family members with varying dietary requirements, food insecurity, minimal cooking and shopping skills, and lack of transportation. When social determinants of health are identified as barriers, physicians should refer patients to available community resources (Table 1).9,10 Physicians can access screening tools and a database of local area supportive services to connect patients with available community nutrition resources through The EveryONE Project (https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/the-everyone-project/toolkit/assessment.html). Physicians can also ask patients about common self-identified barriers to successful long-term nutrition change, including personal motivation, self-efficacy, and self-regulation skills.11

| Program name | Resources available | Contact information |

|---|---|---|

| Child and Adult Care Food Program | Reimburses childcare centers, daycare homes, afterschool programs, and nonresidential care centers for approved healthy meals and snacks provided to eligible children and older adults that align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans | https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp |

| Commodity Supplemental Food Program | Supplements the diets of low-income adults 60 years or older by providing monthly nutritious U.S. Department of Agriculture–packaged food to support a healthy diet pattern. The program is federally funded, and private and nonprofit institutions facilitate the distribution | https://www.fns.usda.gov/csfp/commodity-supplemental-food-program |

| Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program | Provides educational nutrition resources to help families learn how to shop for and cook healthy food with a limited budget | https://nifa.usda.gov/program/expanded-food-and-nutrition-education-program-efnep |

| Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations | Provides U.S. Department of Agriculture–recommended foods, including traditional food choices, to income-eligible American Indian and non–American Indian households residing on a reservation and to American Indian households living in other approved areas (Alternative to SNAP if limited access to SNAP offices or authorized food stores) | https://www.fns.usda.gov/fdpir/food-distribution-program-indian-reservations |

| National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program | Reimburses public and nonprofit private schools and residential childcare institutions that provide approved healthy low-cost or no-cost breakfast and lunch to eligible children each school day | https://www.fns.usda.gov/nslp https://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/school-breakfast-program |

| Older Americans Act Nutrition Programs (1) Congregate Nutrition Services (2) Home-Delivered Nutrition Program (3) Nutrition Services Incentive Program | The Older Americans Act authorizes the provision of healthy meals and related services in congregate settings for any person 60 years or older and their spouse of any age, encouraging regular socialization opportunities, wellness checks, connection to the community, and other services (1) Provides healthy meals to participating seniors and their spouses in a congregate (community) setting, typically in a senior center, school, church, or other community setting (2) In-home meal deliveries (and informal safety check) are available up to once per day for participating seniors who are frail, homebound, or isolated, and their spouses (3) Provides additional grant funding support for (1) and (2) above; determined by the prior year's relative number of meals to cover the cost of domestically produced foods | https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/news%202017-03/OAA-Nutrition_Programs_Fact_Sheet.pdf https://www.fns.usda.gov/program/assistance-seniors https://www.nutrition.gov/topics/food-assistance-programs/nutrition-programs-seniors https://acl.gov/programs/health-wellness/nutrition-services |

| Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Program | Provides nutrition support for eligible low-income seniors through coupons that can be exchanged for eligible foods at farmers' markets, including locally grown fruits, vegetables, herbs, and honey | https://www.fns.usda.gov/sfmnp/senior-farmers-market-nutrition-program |

| SNAP | Temporary benefits; allows families and older adults with qualifying incomes to purchase approved healthy foods and beverages for their household | https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program SNAP State Directory of Resources: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/state-directory |

| SNAP Education | State-based program; provides food and educational resources to support adults in making healthy food choices within a limited budget | https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/state-snap-ed-programs |

| Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children | Provides nutrition support benefits to purchase healthy food and medically indicated special infant formulas and medical foods; available to pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding individuals, infants, and children up to five years of age who are determined by a health care professional to be at “nutrition risk” and who meet certain income and state residency requirements | https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/wic/wic-fact-sheet.pdf |

| Summer Food Service Program | Reimburses approved sponsor organizations including school districts, local government agencies, camps, or private nonprofit organizations that provide no-cost approved healthy meals (up to three meals daily) when school is not in session to eligible children enrolled in an activity program at the approved site | https://www.fns.usda.gov/sfsp/summer-food-service-program |

| The Emergency Food Assistance Program | Provides 100% American-grown U.S. Department of Agriculture–recommended foods and administrative funds to states to supplement low-income Americans' diets with emergency food assistance at no cost | https://www.fns.usda.gov/tefap/emergency-food-assistance-program |

| U.S. Department of Agriculture National Hunger Clearinghouse | Supports low-income individuals or communities by providing food resources such as meal sites, food banks, and other nearby available social services | https://www.fns.usda.gov/partnerships/national-hunger-clearinghouse U.S. Department of Agriculture National Hunger Hotline: 1-866-3-HUNGRY (1-866-348-6479) or 1-877-8-HAMBRE (1-877-842-6273) Hours: 7: 00 a.m. to 10: 00 p.m. eastern standard time Text 914-415-6617 with a question using keywords (e.g., “food,” “summer,” “meals”) to receive an automated response with a list of resources located near an address or zip code |

2. Dietary intake pattern: realistically, what foods do you eat on a regular basis?

The typical American diet pattern does not align with the USDA 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans due to inadequate intake of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and an excess of meat-based proteins and processed foods (including added sugars and saturated fats).3 If a patient responds “usually/often” more than “rarely/never” on the REAP-S v.2, suggesting lower diet quality, or if a full assessment is otherwise indicated, physicians can use a food recall method to determine whether a patient's daily sources of calories generally follow dietary reference intake guidelines. A previous American Family Physician article reviewed the USDA 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans,12 and a brief summary of recommended nutrition guidelines by age group is included in Table 2.3,13 The REAP-S v.2 asks patients about intake of plant-based protein sources such as legumes, nuts, and seeds, as well as dairy alternatives such as soy and almond milk in its screening questions, which helps improve accuracy of responses from patients with plant-based diet patterns.

| Infants 0 to 6 months: Feed infants human milk exclusively When human milk is unavailable, feed infants iron-fortified infant formula Provide supplemental vitamin D soon after birth to infants drinking human milk and those drinking less than 1 L per day of vitamin D–fortified infant formula Avoid honey and unpasteurized dairy, cheese, or juice Infants 6 to 12 months: Continue to feed human milk (or iron-fortified formula) through at least 12 months Introduce a variety of nutrient-dense complementary foods (including potentially allergenic foods) from all food groups (begin at 6 months, but not before 4 months) Encourage foods rich in iron and zinc (especially in infants drinking human milk) Avoid foods or beverages with added sugars until 2 years of age Limit foods and beverages with higher sodium content Avoid honey and unpasteurized dairy, cheese, and juice Toddlers 12 to 24 months: Transition from human milk or formula as the primary source of daily calorie intake to whole foods Introduce cow's milk or dairy alternative beverage when weaning from human milk or formula Vegetables: 2/3 to 1 cup per day Fruits: ½ to 1 cup per day Grains: 13/4 to 3 oz per day Dairy: 12/3 to 2 cups per day Protein: 2 oz per day Oils: 9 to 13 g per day Discretionary calories: no more than 4 oz of 100% juice per day, no soda or sweetened drinks until 2 years of age Avoid unpasteurized dairy, cheese, or juice | ||

| Preschool-aged children 3 to 5 years: | Adults 19 to 59 years: | |

| Vegetables: 1 to 2½ cups per day | Vegetables: 2 to 4 cups per day | |

| Fruits: 1 to 2 cups per day | Fruits: 1½ to 2½ cups per day | |

| Grains: 3 to 6 oz per day | Grains: 5 to 10 oz per day | |

| Dairy: 2 to 2½ cups per day | Dairy: 3 cups per day | |

| Protein: 2 to 5½ oz per day | Protein: 5 to 7 oz per day | |

| Oils: 15 to 24 g per day | Oils: 22 to 44 g per day | |

| Discretionary calories: no more than 130 to 280 kcal per day | Discretionary calories: no more than 100 to 440 kcal per day | |

| Children 6 to 8 years: | Adults 60 years and older: | |

| Vegetables: 1 to 2½ cups per day | Vegetables: 2 to 3½ cups per day | |

| Fruits: 1 to 2 cups per day | Fruits: 1½ to 2 cups per day | |

| Grains: 3 to 6 oz per day | Grains: 5 to 9 oz per day | |

| Dairy: 2 to 2½ cups per day | Dairy: 3 cups per day | |

| Protein: 2 to 5½ oz per day | Protein: 5 to 6½ oz per day | |

| Oils: 15 to 24 g per day | Oils: 22 to 34 g per day | |

| Discretionary calories: no more than 130 to 280 kcal per day | Discretionary calories: no more than 100 to 350 kcal per day | |

| Children 9 to 13 years: | Pregnant and postpartum patients: | |

| Vegetables: 1½ to 3½ cups per day | Vegetables*: 2½ to 3½ cups per day | |

| Fruits: 1½ to 2 cups per day | Fruits: 1½ to 2½ cups per day | |

| Grains: 5 to 9 oz per day | Grains: 6 to 10 oz per day | |

| Dairy: 3 cups per day | Dairy*: 3 cups per day | |

| Protein: 4 to 6½ oz per day | Protein†: 5 to 7 oz per day | |

| Oils: 17 to 34 g per day | Oils: 24 to 36 g per day | |

| Discretionary calories: no more than 50 to 350 kcal per day | Discretionary calories: no more than 140 to 370 kcal per day | |

| Children 14 to 18 years: | ||

| Vegetables: 2½ to 4 cups per day | Increased daily calorie requirement by stage of pregnancy or lactation for healthy pre-pregnancy weight: | |

| Fruits: 1½ to 2½ cups per day | 1st trimester | 0 calories |

| Grains: 6 to 10 oz per day | 2nd trimester | +340 calories |

| Dairy: 3 cups per day | 3rd trimester | +452 calories |

| Protein: 5 to 7 oz per day | 1st 6 months of lactation | +330 calories |

| Oils: 24 to 51 g per day | 2nd 6 months of lactation | +400 calories |

| Discretionary calories: no more than 140 to 580 kcal per day | ||

Food frequency questionnaires, food records, and 24-hour recalls are commonly used to quantify dietary intake and can be obtained through smartphone applications and online or in hard-copy journals. The online Automated Self-Administered 24-Hour Dietary Assessment Tool (ASA24)—available at https://asa24.nci.nih.gov; first-time users can register at https://asa24.nci.nih.gov/researchersite/—was developed by the National Cancer Institute for research and clinical use and is validated in comparison to time-intensive interviewer-administered 24-hour recalls.14,15 The ASA24 can be completed by patients at home and generates an automatically coded, comprehensive nutrition analysis that physicians can use to better understand a patient's general nutrition habits, including meal timing and discretionary calorie intake. Discretionary calories generally should make up only 10% to 15% of dietary reference intake, although recommendations vary based on individual activity level and metabolic demand.3 Physicians can also reference the USDA Dietary Reference Intake Calculator for Healthcare Professionals (https://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/dri-calculator/) to estimate an individual's dietary reference intake based on their age, sex, height, weight, activity level, and, as applicable, pregnancy or lactation status.

Family physicians should ask patients whether they follow a specific diet pattern. The abundance of information about popular diet patterns in nonmedical media and in medical literature can be challenging for patients to navigate. Patients often choose a particular diet pattern with a specific goal in mind; for example, a patient may follow the Mediterranean diet or the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet in an effort to decrease weight, blood pressure, and cardiovascular risk.16–18 The benefits of several common diet patterns were addressed in a previous American Family Physician article,19 and a brief summary of popular diet patterns is included in Table 3.4,16–18,20–22

| Diet pattern type or name and macronutrient distribution (% of daily calorie intake) | General principles and evidence |

|---|---|

| Counting macronutrients No specific macronutrient distribution | Macronutrient distribution ratios vary within a total daily energy goal to meet body composition goals, including decreased overall weight, increased muscle mass, or decreased body fat percentage Common among athletes |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Protein: ~15% Carbohydrate: ~55% to 60% Fat: ≤ 21% to 30% | Daily consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and lower-fat or fat-free dairy products; and limited discretionary calories from added sugar and saturated fats Emphasis on sodium restriction (up to 1,500 mg to 2,300 mg total daily) Moderate- to low-certainty evidence for improved weight loss and cardiovascular risk markers |

| Healthy Mediterranean diet pattern Protein: ~15% Carbohydrate: ~55% to 60% Fat: ≤ 21% to 30% | Daily intake of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, beans, nuts and seeds, and olive oil Weekly intake of fish, beans, eggs, poultry Moderate dairy intake Light to moderate alcohol intake Limited red meat as a protein source Lifestyle focus on sharing meals with others, remaining physically active Moderate- to low-certainty evidence for improved weight loss and cardiovascular risk markers Long-term cardiovascular benefit of reduced serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; may also decrease development of chronic disease such as cardiovascular disease, some cancers, depression, diabetes mellitus, and obesity |

| Healthy vegetarian diet Protein: 10% to 15% Carbohydrate: ~60% Fat: ≤ 20% | Emphasis on whole food choices: vegetables, fruit, nuts, seeds, beans, legumes, grains, healthy plant-based fats, and proteins Moderate- to low-certainty evidence for improved weight loss and markers of cardiovascular risk |

| Intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating No specific macronutrient distribution | Patients generally fast anywhere from 12 to 24 consecutive hours 16-hour fast and 8-hour eating period (most common) With equal daily calorie intake, there is no significant difference between intermittent fasting and calorie restriction with consistent mealtimes |

| Ketogenic diet (extremely low-carbohydrate/high-fat diet) Protein: 20% Carbohydrate: 5% Fat: 75% | Goal is to mimic a fasting state and induce constant ketosis, which may cause adverse health effects Moderate- to low-certainty evidence for improved weight loss, blood pressure, blood glucose, and insulin control Limited evidence for long-term effectiveness |

| Low-carbohydrate/high-fat diets (e.g., Atkins, South Beach, Zone) Protein: ~30% Carbohydrate: 40% Fat: 30% to 55% | Limited fruit and vegetable intake Emphasis on fat and protein intake Unsaturated fats preferred, but difficult to limit saturated fats to ≤ 10% in this diet pattern |

| Low-fat/high-carbohydrate diet (also called traditional calorie or energy restriction diet [e.g., Ornish, Rosemary Conley]) Protein: 10% to 15% Carbohydrate: ~60% Fat: ≤ 20% | In very low-fat/high-carbohydrate diets, fat intake is further restricted to ≤ 15% of daily calorie intake) Limited unsaturated and trans fats Moderate- to low-certainty evidence for improved weight loss and markers of cardiovascular risk |

| Paleolithic diet Protein: 15% to 30% Carbohydrate: 40% to 60% Fat: 20% to 55% | Emphasis on whole food choices including vegetables, fruit, nuts, seeds, meat, fish, herbs, spices, and healthy fat Restricts grains, legumes, processed foods, sugar, soft drinks, most dairy products, artificial sweeteners, vegetable oils, margarine, and trans fats Neither the most effective nor least effective popular diet intervention for weight loss based on a small number of studies with high- or moderate-certainty evidence |

| Points-based diets (e.g., Weight Watchers) Protein: ~15% Carbohydrate: ~55% to 60% Fat: ≤ 21% to 30% | Some diets assign points to various foods or assign foods into different categories Moderate- to low-certainty evidence for improved weight loss and markers of cardiovascular risk |

Physicians should ask about energy (i.e., calorie) restriction in a patient's diet pattern and their adherence to diet patterns. Regardless of diet type, energy restriction is an independent key factor in successful weight loss,20 and dietary adherence is more closely associated with weight loss after one year than the diet pattern itself.16,18,20,23 Physicians should clarify nutrition habit patterns, including how often patients consume home-cooked, restaurant-cooked, and fast-food meals, as well as the frequency of meals eaten with distractions (such as television or other screen time) and meals eaten alone or with others. Regular family meals are associated with healthier dietary intake in children and parents,24 and watching television during meals is inversely associated with diet quality.25,26

Because childhood nutrition deficiency is associated with adverse cognitive and developmental outcomes and decreased academic achievement through late adolescence, accurate nutrition history taking in children is also imperative.27 Exclusive breastfeeding (or bottle-feeding with expressed breast milk) is recommended for all infants up to six months of age because of its association with improved immune function, cognitive development, reduced childhood obesity, and many other health benefits.3,13,27 Physicians should ask about and then encourage parents to introduce nutrient-dense complementary foods in infants older than six months. Because of the risk of early atherosclerotic disease development, physicians should determine whether toddlers and older children are consuming a consistent balance of healthy beverages and nutrient-dense foods that are low in saturated and trans fats.3,13,27 In addition, physicians should ask parents how they role model healthy eating behaviors.3,13 Physicians can direct parents to complete the MyChild at Meal Time questionnaire, a brief validated tool that identifies parenting nutrition habits that may increase risk of poor nutrition and obesity in children (http://healthykids.ucdavis.edu/?parent=True).28

3. Metabolic demand and comorbid conditions: what activities, jobs, and exercise do you do each week? What are your current medical conditions?

Physicians can quickly obtain a general understanding of overall energy expenditure if they can identify functional demands of the patient's routine regarding occupation, routine activity, and exercise. Patients can estimate the number of minutes they perform vigorous, moderate, and light exercise, and minutes spent sitting each week with the widely used International Physical Activity Questionnaire–Short Form. It is important to note that recent evidence suggests patients often overestimate activity on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire–Short Form compared with objective measurement.29

Physicians should also inquire about medical conditions the patient has or is at risk of developing that could be affected by poor nutrition health. These include diet-related chronic diagnoses, current pregnancy or desire for future fertility, disordered eating, and history of weight loss surgery. Current or potential medical conditions or metabolic demands may prompt nutrition referral for specialized dietary recommendations. For example, according to U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations, patients with cardiovascular disease risk factors should be offered or referred for nutrition counseling.30

4. Consideration of additional supplement or substance use: what is your typical caffeine, alcohol, and supplement intake?

Physicians should quantify caffeine, alcohol, and other recreational substance intake and consider the impact on their patient's nutrition health. Increased use of caffeine, alcohol, or other substances may affect appetite and nutrition habits, and lead to protein or micronutrient insufficiency.31 Moderate coffee consumption (3 to 4 cups daily) is associated with relative risk reduction of cardiovascular disease morbidity and all-cause mortality.32 Light to moderate alcohol intake (Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends no more than two drinks daily for men and one drink daily for women)3 has been proven to decrease risk of cardiovascular disease, although recent evidence suggests that even mild to moderate alcohol use increases the risk of some cancers and other adverse health outcomes.33

Physicians should inquire about daily multivitamin intake in patients of all ages. Although most adults in the United States ingest adequate micronutrients through diet and do not require multivitamin supplementation, one-third still take daily multivitamins.34 Multivitamin supplementation may lead to excess micronutrient consumption; however, it does not increase mortality, nor does it reduce the risk of developing chronic disease.34,35 Statistically, the patients least likely to take multivitamins have the highest risk of nutritional inadequacy, which is often related to differences in social determinants of health.34

Physicians should ask about and encourage specific micro-nutrient supplementation in certain populations to ensure adequate intake, including pregnant patients (folate), infants (vitamin D), older adults (calcium and vitamin D), patients undergoing weight loss surgery (calcium, copper, fat soluble vitamins, folate, iron, thiamine, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and zinc), and patients with very strict vegan diets (calcium, iodine, iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and zinc).3,35–37 Additionally, physicians who determine from nutrition history taking that a patient may not consume sufficient micronutrients through food sources may consider further evaluation or recommend vitamin supplementation.13,27,34

For patients who are athletes, physicians should ask about performance supplements, which may contain undisclosed contaminants or illicit substances. Further discussion of safe supplement integration into an athlete's dietary regimen can be accomplished through nutrition referral.38 Physicians can ask whether patients specifically time their intake of carbohydrates or protein to maximize endurance event performance or to increase muscle protein synthesis and speed recovery.38 Physicians should also routinely screen athletes for eating disorders because of the higher prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviors in athletes compared with nonathletes.39

After Taking an Initial Nutrition History

In partnering with patients to make individualized nutrition changes, evidence supports the use of setting goals that can be self-monitored.40 About 85% of adults in the United States own a smartphone, which can be used to collect data that aid in nutrition history taking and in self-monitoring of nutrition goals.41 Moderate-certainty evidence suggests that patients have better outcomes when using smartphones for nutrition tracking compared with food journals or no tracking at all.42 Clinicians who use smartphone apps themselves more frequently address nutrition health and offer counseling through nutrition-tracking apps,42 such as the Start Simple With MyPlate app (https://www.myplate.gov/resources/tools/startsimple-myplate-app). In-person motivational interviewing, especially combined with other active goal-oriented therapies, can effectively support long-term behavior change in health-related outcomes, and it can be used to create motivation for addressing nutrition change.11

Many patients warrant referral for interdisciplinary nutrition care with a registered dietitian or with a behavioral health specialist; this includes patients with chronic disease or medical diagnoses for which specific diet patterns are recommended. Even after referral, physicians should continue to re-evaluate patient nutrition history for interval change at follow-up visits. This approach empowers patients to make positive nutrition choices and emphasizes lasting habits that will decrease morbidity and mortality.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Hark and Deen.1

Data Sources: An evidence summary generated from Essential Evidence Plus was reviewed and relevant studies referenced. A PubMed search was completed using the following key terms: nutrition primary care, nutrition medical school curriculum, physician nutrition counseling, popular diet comparison, nutrition outcomes, physician intervention, motivational interviewing, macronutrient recommendations, dietary guidelines, food frequency questionnaire, dietary survey, 24-hour recall, validated nutrition screening tool, athlete nutrition, sports nutrition, micronutrient deficiency, resident perception nutrition education, effectiveness of nutrition counseling, effectiveness of weight counseling, barriers to nutrition counseling, physician barriers to nutrition, patient barriers to nutrition, motivational interviewing nutrition, counseling technique nutrition, mindful eating health outcomes, timed restricted eating nutrition, intermittent fasting, MyPlate improve dietary outcomes, food insecurity nutrition counseling, nutrition coffee health outcomes, nutrition alcohol health outcomes, malnutrition substance use, malnutrition addiction, dietary guidelines children, dietary guidelines pediatrics, dietary guidelines bariatric surgery, dietary insufficiency bariatric surgery, vegetarian diet nutrition, smartphone nutrition, and nutrition-tracking apps. The searches included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Pertinent United States and international society and governmental guidelines and data sheets were also reviewed. Search dates: January 2021 through January 2022.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.