Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(6):675-683

Patient information: See related handout on hip fractures, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Hip fractures are common causes of disability, with mortality rates reaching 30% at one year. Nonmodifiable risk factors include lower socioeconomic status, older age, female sex, prior fracture, metabolic bone disease, and bony malignancy. Modifiable risk factors include low body mass index, having osteoporosis, increased fall risk, medications that increase fall risk or decrease bone mineral density, and substance use. Hip fractures present with anterior groin pain, inability to bear weight, or a shortened, abducted, externally rotated limb. Plain radiography is usually sufficient for diagnosis, but magnetic resonance imaging should be obtained if suspicion of fracture persists despite normal radiography. Operative management within 24 to 48 hours of the fracture optimizes outcomes. Fractures are usually managed by surgery, with the approach based on fracture type and location; spinal or general anesthesia can be used. Nonsurgical management can be considered for patients who are not good surgical candidates. Pre- and postoperative antistaphylococcal antibiotics are given to prevent joint infection. Medications for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis are also recommended. Physicians should be alert for the presence of delirium, which is a common postoperative complication. Early postoperative mobilization, followed by rehabilitation, improves outcomes. Subsequent care focuses on prevention, with increased physical activity, home safety assessments, and minimizing polypharmacy. Two less common hip fractures can also occur: femoral neck stress fractures and insufficiency fractures. Femoral neck stress fractures typically occur in dancers 20 to 30 years of age, endurance athletes, and military service members, often because of training overload. Insufficiency fractures due to compromised bone strength occur without trauma in postmenopausal women. If not recognized and treated, these fractures can progress to complete and displaced fractures with high rates of nonunion and avascular necrosis.

Hip fractures are among the 10 most common causes of disability globally, with more than 300,000 hip fractures occurring annually in the United States.1,2 The average age of patients with hip fractures is 80 years, and 75% to 80% of injuries occur in women.3,4 Mortality rates reach 10% at one month and approach 30% at one year.5–7 Of those who live, 11% are bedridden, 16% require admission to long-term care facilities, and 80% require a walking aid.8,9

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not transfuse asymptomatic postoperative patients with hip fracture who have a hemoglobin level higher than 8 g per dL (80 g per L). | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons |

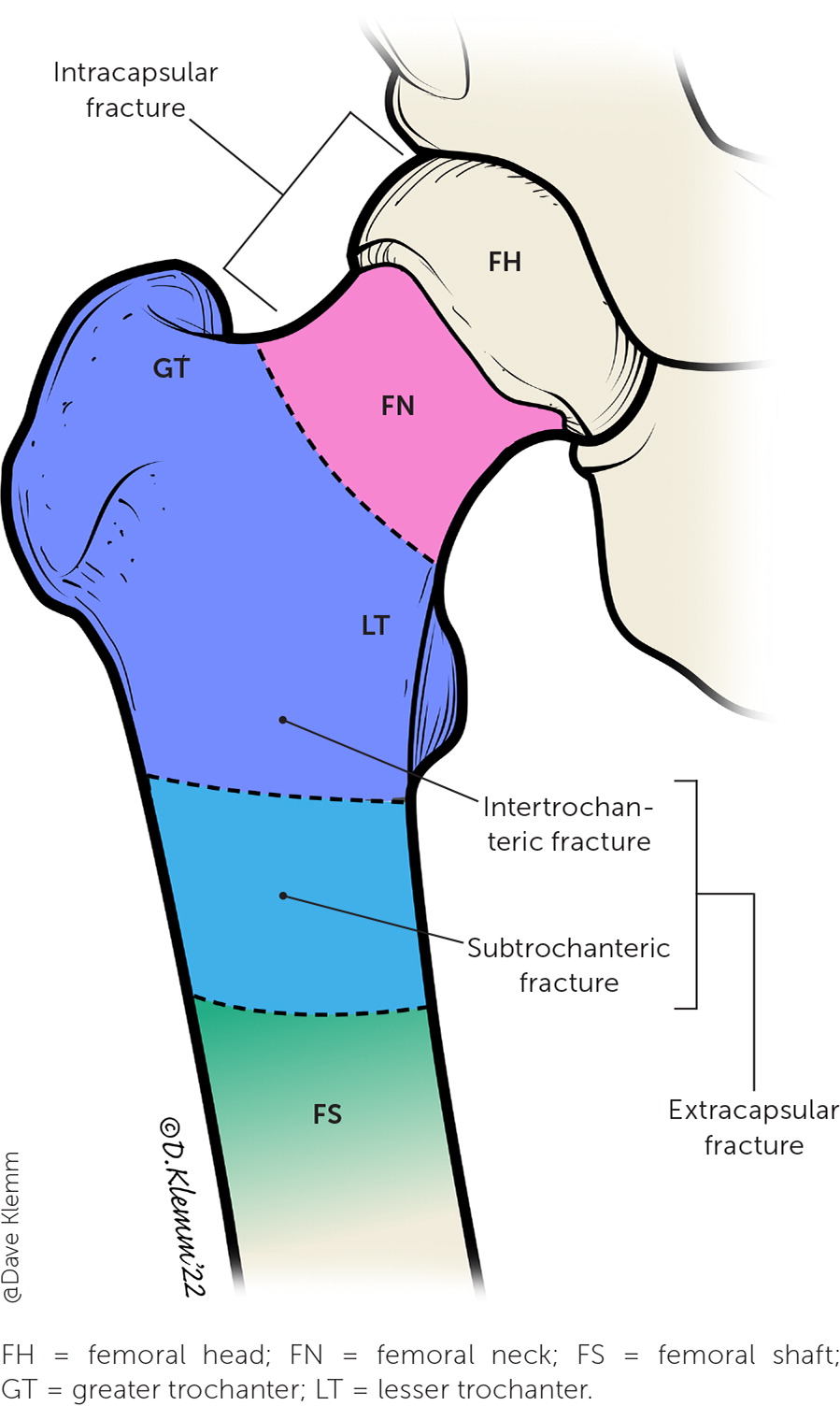

Hip fractures account for 87% of all femur fractures.3 They are classified by their location relative to the hip capsule and their degree of displacement (Figure 1). Intracapsular (femoral neck) fractures, comprising 45% to 53%, and intertrochanteric (between the greater and less trochanter) fractures, comprising 38% to 50%, are the most common of all hip fractures.9,10 Subtrochanteric fractures account for only 3%, and femoral shaft and lower femoral fractures account for about 5% each.3

In addition to the more common fractures, this review also discusses femoral neck stress fractures and insufficiency fractures. These fractures are uncommon in the general population and are often misdiagnosed or even missed 75% of the time, but they are critical to consider in patients presenting with anterior hip or groin pain because of their risk of progressing to complete, displaced fractures with high rates of nonunion and avascular necrosis.11

Risk Factors

| General hip fracture Nonmodifiable12–17 Advanced age Bony malignancy or metastases Female sex History of fracture Lower socioeconomic status Metabolic bone disease Modifiable12,15,18–21 Chronic medications (e.g., corticosteroids, levothyroxine, loop diuretics, proton pump inhibitors) Falls High caffeine intake Low body mass index (< 18.5 kg per m2) Low vitamin D levels Moderate to high alcohol intake Osteoporosis or low bone mineral density Physical inactivity or poor functional status Smoking | Stress fracture of the hip Nonmodifiable16,22 Delayed menarche Elevated cortisol levels Female sex Femoral acetabular impingement Metabolic bone disease Modifiable16,22 Gluteus medius weakness Low aerobic fitness Low vitamin D levels Military service members Participation in long-distance running Relative energy deficiency Smoking Sudden increase in physical training distance or intensity or lack of recovery |

NONMODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS

The most significant nonmodifiable risk factors for hip fracture are older age and female sex. Women older than 85 years have a 10-fold increased risk compared with women in their 60s.12 Other nonmodifiable risk factors include history of any fracture, lower socioeconomic status, metabolic bone disease, and bony malignancy.13–17

MODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS

Several modifiable risk factors, of which falls are the most significant, are associated with up to 90% of hip fractures.18 Low body mass index (less than 18.5 kg per m2) is associated with a threefold higher risk.15,19 Low bone mineral density (BMD) also increases risk for fracture, with some estimates finding osteoporosis (T-score less than −2.5) associated with up to 50% of fractures.12,20 Physical inactivity carries a twofold higher risk because lack of weight-bearing activity promotes BMD loss.19,21 Low general health and low vitamin D levels are also associated with low BMD and hip fracture.15

Several medications also increase risk. Corticosteroids, levothyroxine, proton pump inhibitors, and loop diuretics can all decrease BMD, leading to higher fracture risk.12,18,19 Antihypertensives increase risk for postural hypotension and, therefore, falls and subsequent fractures.18 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, benzodiazepines, and opioids may cause sedation and postural hypotension, increasing fall and fracture risk.12,18 Moderate to high alcohol intake (more than 27 g daily), smoking, and high caffeine intake (more than three cups of coffee per day) increase the odds of fracture by 1.5 to two times, likely secondary to appetite suppression and decreased BMD.15,19

Presentation

Patients typically present with anterior groin pain referring to the thigh or buttock and inability to bear weight on the affected limb after a fall or other trauma.12,23,24 Physical examination may reveal visual deformity of the hip; external rotation, abduction, or shortening of the affected limb; tenderness to palpation over the groin and anterior hip; pain with log roll maneuver (gentle internal and external rotation of lower leg and thigh); or inability to perform a straight leg raise while supine.12,23–25 Ecchymosis is typically not initially present. Neurovascular status of the affected limb with distal pulses and sensation to light touch should be assessed.

Diagnosis

Cross-table lateral hip and anteroposterior pelvis radiography are the initial diagnostic tests for hip fracture12,17,26 (Figure 212). Frog-leg views can worsen fracture displacement and are not recommended.12 Magnetic resonance imaging is reserved for continued suspicion of fracture despite negative plain radiography.17 Classification as intracapsular, extracapsular, displaced, or nondisplaced drives management.9

Management

Physicians caring for patients with acute hip fractures face three questions. Is surgery an option? How quickly should surgery be performed? What type of procedure is best?

IS SURGERY AN OPTION?

Operative management of hip fractures is usually the preferred treatment because it reduces mortality rates, whereas nonoperative treatment carries a fourfold increased risk of death at one year.9,27 Nonoperative management may be considered for patients who are nonambulatory, severely debilitated, or who have end-stage terminal illness; it requires shared decision-making regarding goals of care.27

HOW QUICKLY SHOULD SURGERY BE PERFORMED?

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2021 clinical practice guideline recommends operative management within 24 to 48 hours of injury unless a delay is needed to stabilize comorbidities.28 Early operative management improves pain control, decreases length of hospitalization, and reduces complications.28 In an international randomized controlled trial of 3,000 patients, no difference in mortality rates was demonstrated with accelerated surgery time (less than six hours), but accelerated surgery did show a decreased risk of perioperative complications, faster postoperative mobilization, and decreased time to discharge.29 Prolonged wait time (more than 24 hours) to surgery is associated with increased 30-day mortality.30

WHAT TYPE OF PROCEDURE IS BEST?

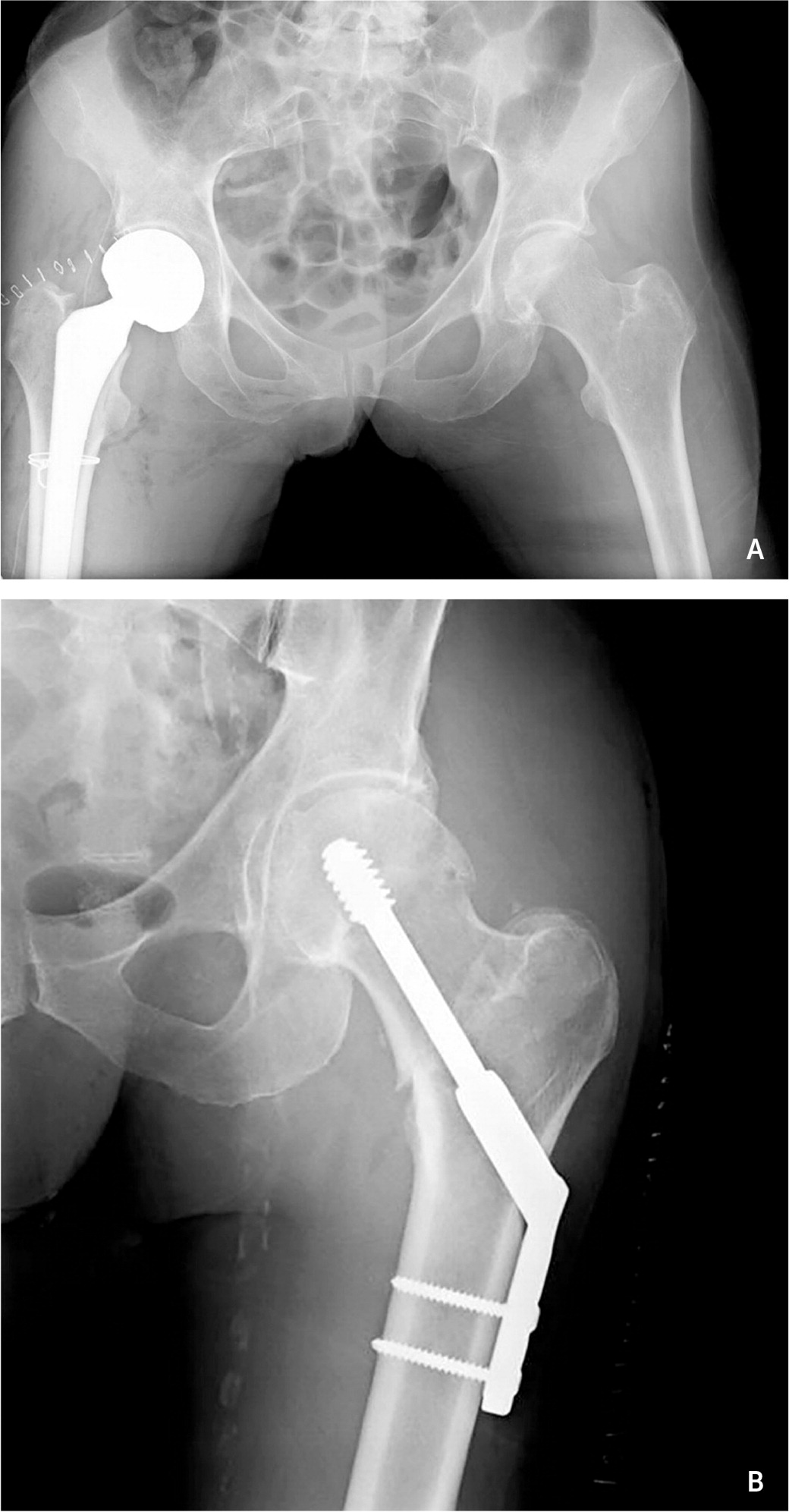

The surgeon involved in the patient’s care will determine the optimal procedure. In general, however, internal fixation is used for nondisplaced femoral neck fractures in younger patients. For displaced femoral neck fractures, closed reduction and pinning is often used in younger patients to avoid hip arthroplasty (joint replacement), although this carries risk of avascular necrosis.9,28 For those older than 65 years, arthroplasty is generally preferred9 (Figure 3A12). Intertrochanteric and extracapsular fractures are typically repaired with open reduction and internal fixation12,28 (Figure 3B12). Subtrochanteric fractures usually require an intramedullary rod and nail to stabilize the fem-oral head and shaft.12,28

Perioperative Management

ANTIBIOTICS

Antibiotics with activity against Staphylococcus aureus are recommended one to two hours before surgery and 24 hours postoperatively to prevent joint infection.12 Typical regimens are cefazolin (1 to 2 g intravenously every eight hours) or, if allergic to cephalosporins, vancomycin (1 g intravenously every 12 hours).12,31

ANESTHESIA

Spinal or general anesthesia are used intraoperatively. A randomized superiority trial of 1,600 patients demonstrated that incidence of death or the ability to ambulate at 60 days did not differ between spinal vs. general anesthesia.32 Peripheral nerve blocks on admission and postoperatively offer additional pain management and improve outcomes.28,33

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM PROPHYLAXIS

Patients with hip fracture are at high risk of venous thromboembolism caused by immobility, so chemoprophylaxis is recommended over mechanical prophylaxis alone.28 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2021 clinical practice guidelines make no recommendation about the preferred agent.28 However, meta-analyses from 2020 and 2021 showed that aspirin is an effective, safe, and inexpensive alternative for venous thromboembolism prevention following arthroplasty compared with low-molecular-weight heparin or direct oral anticoagulants.34–36

TRANSFUSION

The threshold for blood transfusion in asymptomatic postoperative patients with hip fracture is a hemoglobin level less than 8 g per dL (80 g per L), unless cardiac contraindications exist.28

Postoperative Care

An interdisciplinary care team, including orthopedic surgeons, hospitalists, dietitians, geriatric services, and physical and occupational therapists, reduce postoperative complications and in-hospital mortality and improve functional status.28

DELIRIUM

Hip fracture–associated delirium is a common complication in hospitalized patients, both pre- and postoperatively.37 It often occurs without an alternate underlying cause and typically resolves spontaneously without intervention.37 The perioperative care guideline from the American College of Surgeons and the American Geriatrics Society provides an approach to preventing and detecting delirium and other postoperative complications when caring for patients with hip fractures.38

REHABILITATION

Early rehabilitation and weight-bearing initiated within 24 hours postoperatively are associated with improved mobility outcomes.39 Following hospital discharge, inpatient and home-based rehabilitation are options, depending on the specific needs of the patient.40 Physical therapists can help guide and individualize the approach to rehabilitation.

Prevention

BONE MINERAL DENSITY

Decreased BMD is a key risk factor for hip fractures. Patients with acute hip fractures should receive postoperative oral bisphosphonates, and those with decreased BMD should receive longer-term treatment to prevent secondary fractures with agents, including bisphosphonates, parathyroid analogs (teriparatide or abaloparatide [Tymlos]), and RANKL inhibitors (denosumab [Prolia] or romosozumab [Evenity]).41

Vitamin D levels should also be checked because individuals older than 65 years with vitamin D concentrations less than 10 ng per mL (24.96 nmol per L) are at greater risk for decreased muscle strength, low bone mineral density, and hip fractures; vitamin D repletion may be beneficial for these patients.15,42 A 2018 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force review, however, concluded that vitamin D supplementation has no benefit in fall prevention for older adults not known to be deficient.43

The benefit of other vitamin therapies is uncertain. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that multivitamin use may be protective against osteoporotic hip fracture, but randomized controlled trials are lacking.44

Further recommendations on the treatment of osteoporosis can be found in current guidelines.45

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND EXERCISE

Physical activity is effective for primary and secondary prevention of hip fractures,46 and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends exercise to prevent falls in adults older than 65 years.47 Multicomponent physical activity (low- to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise with resistance, strength, and proprioceptive training) reduces osteoporosis and improves hip joint function and quality of life while reducing fall-related injuries by up to 40%.46,48,49 Tai chi, which contains elements of strength and balance training, may reduce the rate of injurious falls by 50%.50

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR OLDER ADULTS

Primary care physicians should consider a full geriatric assessment for patients at high risk for falls. A formal home safety assessment and medication reconciliation should be performed, with deliberate discontinuation of nonessential medications that can increase fall risk or decrease BMD (e.g., psychotropics, antihypertensives, corticosteroids).51–53 Further educational resources for physicians and patients about fall prevention are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/) and the American Geriatrics Society (https://www.healthinaging.org/a-z-topic/falls-prevention).

Femoral Neck Stress Fractures

Femoral neck stress fractures result from consistently high physical demands on normal bone or from normal physiologic loads on structurally compromised bone. The former cause is most prevalent among military service members, endurance athletes, and dancers 20 to 30 of years of age, with risk factors including female sex, delayed menarche, femoral acetabular impingement, relative energy deficiency in sport, low vitamin D level, smoking, sudden increase in training distance or intensity, and lack of recovery after training.16,54–56 The latter cause, commonly called insufficiency fracture, occurs in postmenopausal women and those with metabolic conditions that compromise bone strength (e.g., osteoporosis, hyperparathyroidism, renal disease).57

Both mechanisms lead to overload and mechanical failure and, if not recognized early, may progress to complete and displaced hip fracture. Because of high, poor relative vascular supply of the circumflex femoral arteries around the femoral neck, these fractures carry high rates of nonunion and avascular necrosis.16,57,58

PRESENTATION

Patients with femoral neck stress fracture typically present with anterior groin, buttock, or lateral hip pain, particularly at night and with weight-bearing. There may be an accompanying history of recently increased activity volume or intensity.22

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

DIAGNOSIS

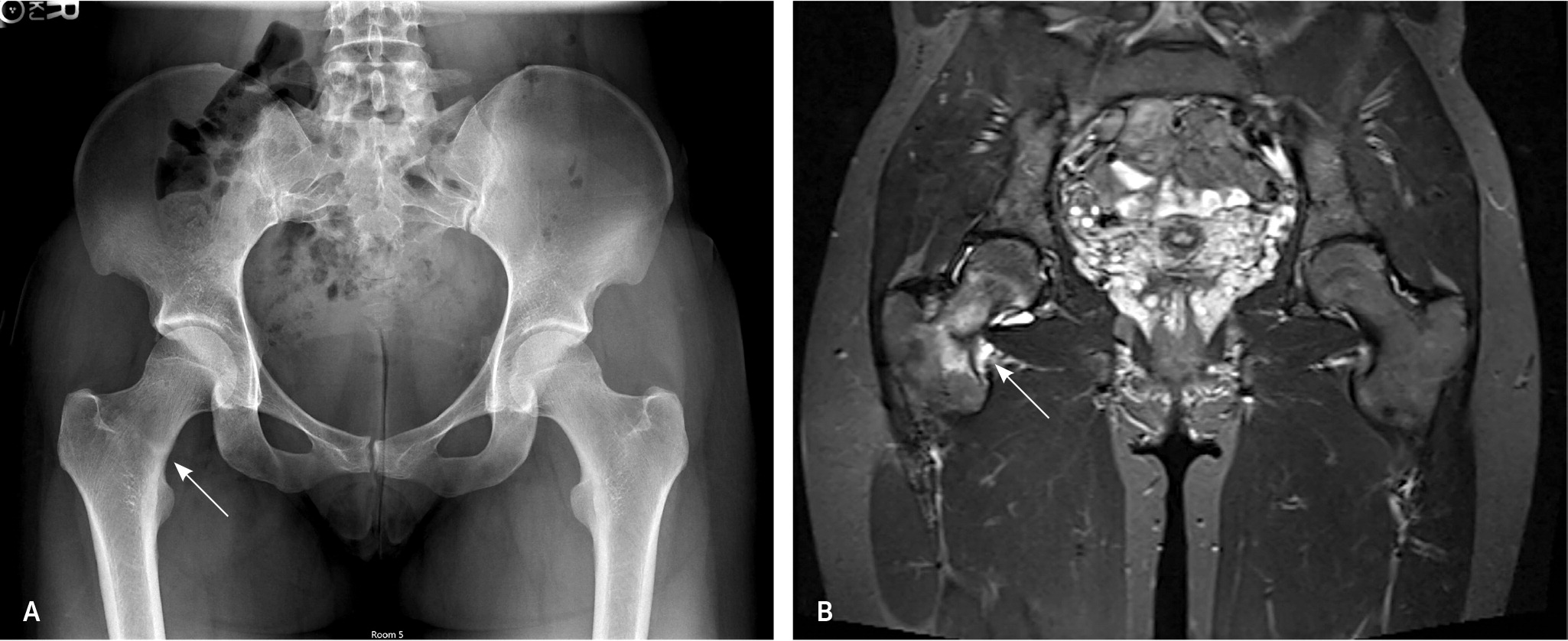

When suspected, the first diagnostic test is plain radiography, which may show loss of cortical density, cortical thickening, or frank fracture54 (Figure 4A). However, plain radiography may appear normal, and if femoral stress fracture is strongly suspected based on the patient’s symptoms and activity history, magnetic resonance imaging of the hip should be performed16,54 (Figure 4B).

MANAGEMENT

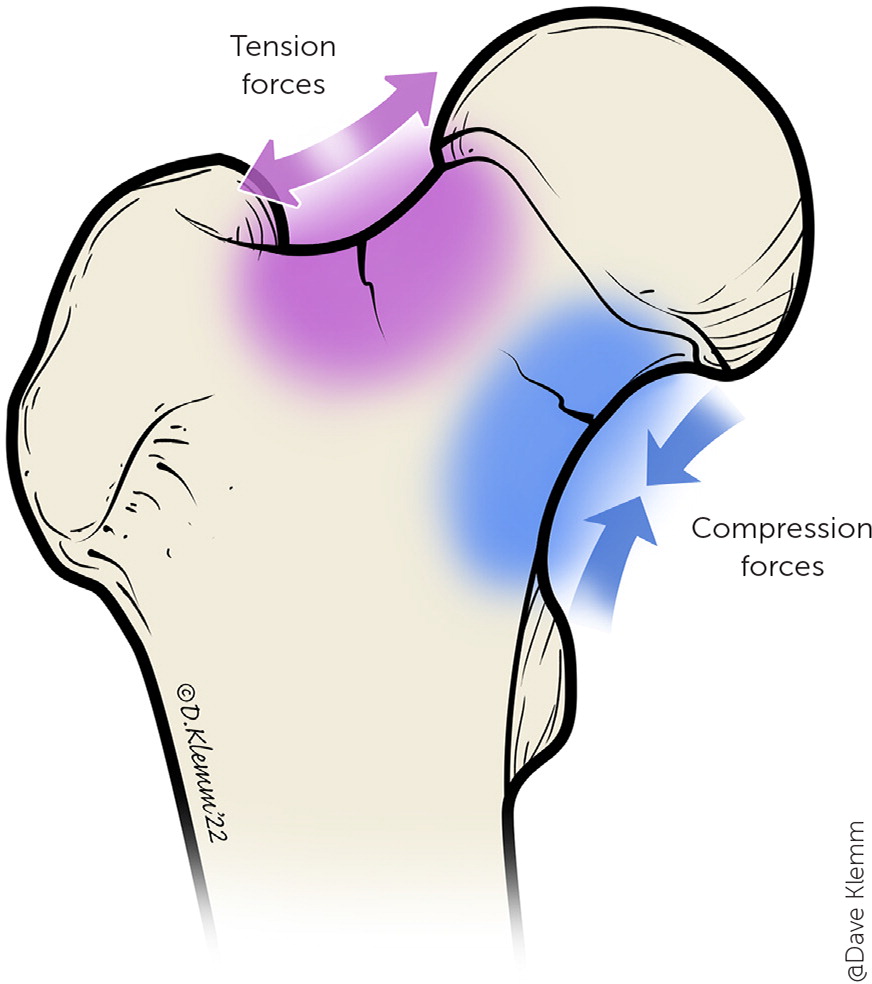

If femoral neck stress fracture is confirmed on imaging, treatment depends on whether the fracture is on the tension side or the compression side (Figure 5). For tension-sided stress fracture, immediate surgical consultation is indicated for consideration of percutaneous screw fixation.62,63 Even with a lower-risk, compression-sided fracture, if surgical consultation recommends no surgery, patients must remain non–weight-bearing until pain improves and repeat imaging demonstrates evidence of healing. Based on expert opinion, gradual progression to weight-bearing activities over the course of four to six weeks can then begin.61

Atypical Femur Fractures

A final consideration is atypical femur fractures, defined as insufficiency fractures that develop because of prolonged use of antiresorptive medications (bisphosphonates or denosumab).64 These medications suppress bone remodeling by inhibiting osteoclasts, leading to accumulation of microdamage, which may progress to complete fracture.64,65

This article updates previous articles on this topic by LeBlanc, et al.12; Rao and Cherukuri25; and Brunner, et al.1

Data Sources: We searched Essential Evidence Plus, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline, PubMed Clinical Queries, and UpToDate. Literature search key words included hip fracture, fall risk, fall prevention, osteoporosis, stress fracture, femoral neck stress fracture, bone stress injury, hip fracture anticoagulation. Search dates: November 5 to December 28, 2021; October 30 to 31, 2022.

The authors recognize Jeffrey Leggit, MD; Scott Grogan, DO; Ben Buchanan, MD; and Tyler Raymond, DO, for their support in the editing process of this article.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of Madigan Army Medical Center, the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.