Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(2):151-158

Patient information: See related handout on joint and soft tissue injections.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Joint and soft tissue injections can be divided into two primary categories: diagnostic and therapeutic. Diagnostic injections facilitate a diagnosis by using a local anesthetic to identify the site of pain or through fluid aspiration for analysis. Therapeutic injections are categorized by the type of injectate and include corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, dextrose prolotherapy, and platelet-rich plasma. Diagnostic and therapeutic injections are most accurate under direct visualization. Corticosteroid injections help treat adhesive capsulitis and tenosynovitis but are not recommended for intratendinous injections. Hyaluronic acid has limited benefits for knee osteoarthritis. Dextrose prolotherapy injections treat tendinopathy and degenerative joint pain. Platelet-rich plasma injections effectively treat common extensor tendinopathy and knee arthritis; however, the evidence does not support its use for other soft tissue injuries. Preparation for injections includes patient education, consent, proper patient positioning, and obtaining the necessary supplies. Local infection, fractures, and allergy to injection substrates are contraindications to joint and soft tissue injections. Potential complications include pain, swelling, and redness. Corticosteroid injections into soft tissue may cause atrophy and depigmentation, and repeated injections can cause cartilage and tendon degeneration. Optimizing conservative, noninjection treatments, such as oral and topical analgesics, activity modification, or rehabilitation, is also important.

Musculoskeletal conditions are reported by 48% of the population and are a significant component of primary care visits.1 Joint and soft tissue injections can serve as diagnostic aids and adjunctive treatments (Table 12). Injections can be categorized as diagnostic or therapeutic. A diagnostic injection clarifies the underlying pathology causing pain. Diagnostic injections introduce a local anesthetic with subsequent evaluation for symptom relief. Aspiration of synovial fluid for substrate analysis is classified as a diagnostic injection; however, it can also be therapeutic for joint effusion or a painful cyst.2

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Intrasheath corticosteroid injections may be effective for treatment of trigger finger and de Quervain tenosynovitis.14,15,17 | B | Inconsistent quality patient-oriented evidence |

| Dextrose prolotherapy is effective in the treatment of common extensor tendinopathy.43,44 | A | Consistent patient-oriented evidence |

| Intra-articular injection of dextrose prolotherapy improves pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis.45–48 | A | Consistent evidence from randomized controlled trials |

| Repeated and frequent intra-articular injections of triamcinolone acetonide decrease cartilage thickness.66,67 | C | Randomized controlled trials with disease-oriented outcomes |

| Joint conditions |

| Chondromalacia |

| Crystalloid arthropathies |

| Effusion |

| Inflammatory arthritis |

| Intra-articular derangement (e.g., meniscal injury) |

| Osteoarthritis |

| Synovitis |

| Soft tissue conditions |

| Bursitis |

| Masses (e.g., ganglion cysts, neuromas) |

| Nerve entrapment |

| Neuropathic pain |

| Tendinopathy |

| Tendon/ligament/muscle disruption |

| Tenosynovitis or tendinopathy |

| Trigger point |

Therapeutic injections provide clinical benefits by relieving pain, restoring function, or both. These injections commonly include corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, dextrose prolotherapy, and platelet-rich plasma.

Diagnostic and therapeutic injections can be performed with and without imaging guidance; however, imaging guidance increases injection accuracy and is warranted in specific anatomic locations, including the glenohumeral joint, femoroacetabular joint, and nerve hydrodissections.3 Knowledge of anatomy, proper patient positioning, and physician preparedness are essential for all injections. A patient's understanding of risks, benefits, and alternatives promotes patient-oriented outcomes.4,5

Diagnostic Injections

Diagnostic injections identify which structure is generating pain when nearby structures overlap the pattern of symptoms. For example, a diagnostic injection can accurately identify the cause of shoulder pain in a patient with both glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joint pain features or if conservative management has been ineffective.

Lidocaine, bupivacaine, and ropivacaine (Naropin) are commonly used in diagnostic injections. Anesthetic injections have a dose-dependent potential for cell damage, most prominently with lidocaine and bupivacaine.6,7 Evidence supports ultrasonography to improve the accuracy of injection of the acromioclavicular joint, biceps tendon sheath, glenohumeral joint, and hip joint.8–10 A targeted soft tissue diagnostic injection providing immediate relief of more than 50% of preprocedural pain clarifies the diagnosis.

Therapeutic Injections

Therapeutic injections should be used with injury-specific rehabilitation and modification of aggravating activities.11 Table 2 summarizes the evidence-based application of therapeutic injection for musculoskeletal conditions.12 Other therapeutic injections, such as botulinum toxin, sclerotherapy, mesenchymal signaling, and other cellular therapies are beyond the scope of this article.

| Therapeutic injectate class | Musculoskeletal pathology |

|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | Adhesive capsulitis Degenerative joint disease* Inflammatory arthropathy (e.g., gout) Nerve entrapment Shoulder impingement Tenosynovitis |

| Dextrose prolotherapy | Degenerative joint disease Ligamentous pathology Tendinopathy |

| Hyaluronic acid | Knee osteoarthritis |

| Platelet-rich plasma | Common extensor tendinopathy Knee osteoarthritis |

CORTICOSTEROID

Indications. High-quality evidence supports the use of corticosteroid injections for adhesive capsulitis, de Quervain tenosynovitis, and trigger finger.13–17 In a systematic review and network meta-analysis evaluating pharmacologic treatments for adhesive capsulitis, the most significant benefit was found in patients with less than two months of symptoms who had intra-articular glenohumeral corticosteroid injections or corticosteroid injections and capsule distention.13 For de Quervain tenosynovitis, tendon sheath corticosteroid injections alone provided greater pain relief compared with corticosteroid injections with splinting, splinting alone, rest, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients 38 to 50 years of age.14 In patients who are pregnant and breastfeeding with de Quervain tenosynovitis, corticosteroid injection is superior to thumb spica splinting.17 In a double-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 50 patients, tendon sheath corticosteroid injections for trigger finger had a significantly higher success rate compared with normal saline injection in decreasing the frequency of triggering and severity of symptoms.15

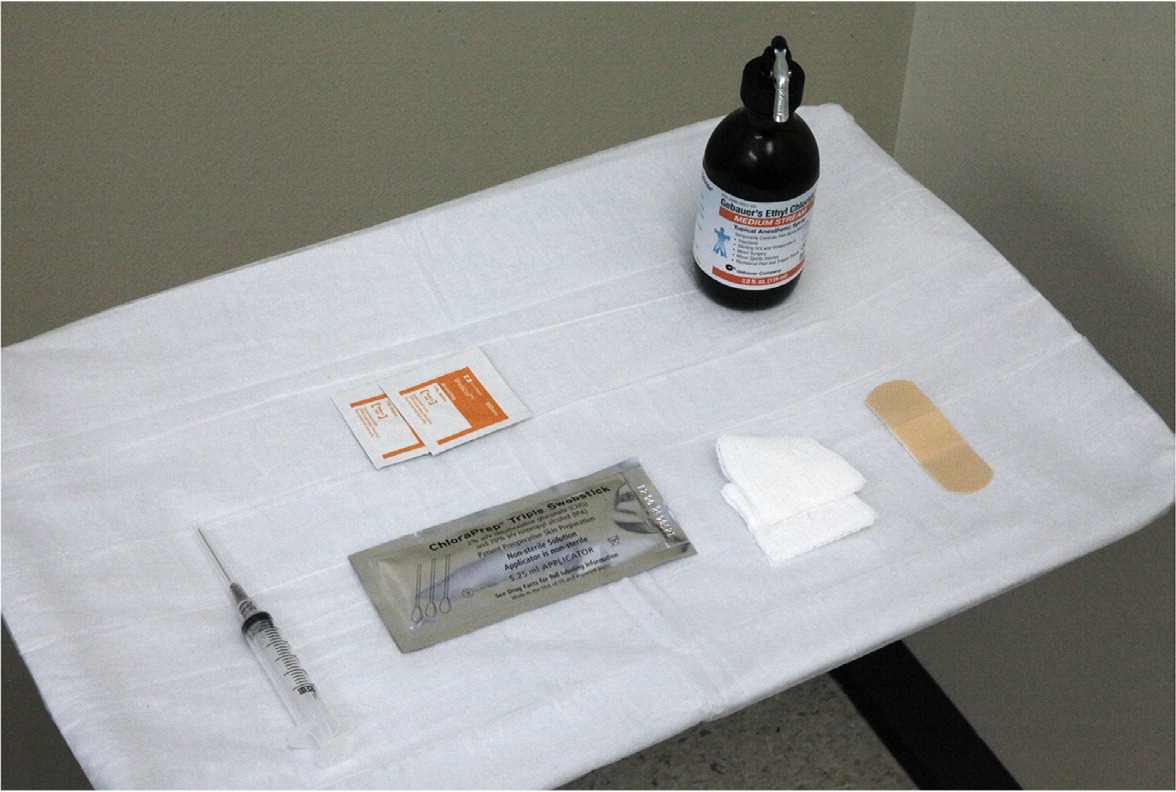

Corticosteroids are also used to treat nerve entrapment (e.g., the median nerve at the carpal tunnel); however, evidence suggests that benefits may be attributed to corticosteroid and physical tissue distortion.18 Tendinopathies such as gluteus medius (greater trochanteric pain) and common extensor tendinopathy (lateral epicondylopathy, tennis elbow) were previously thought to benefit from corticosteroid injections, but extensive evidence shows that rehabilitation outperforms any combination of treatments, including corticosteroid injections.19–21 Table 3 offers composition and needle size guidance for commonly performed landmark-guided corticosteroid injections.12,22–24 Figure 1 provides an example of a setup for a knee injection.

| Anatomic site | Injectate dose | Needle size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% lidocaine (mL) | Triamcinolone acetonide (mg)* | Betamethasone (mg) | Gauge | Length (in) | |

| Intra-articular knee | 3 to 4 | 20 | 6 | 25 | 1.5 to 2 |

| Acromioclavicular joint | 0.5 to 1 | 10 to 20 | 3 to 6 | 25 | 1 to 1.5 |

| Glenohumeral joint | 4 to 6 | 20 | 6 | 22 or 25 | 1.5 to 2 |

| Subacromial space | 4 to 6 | 20 | 6 | 25 | 1.5 to 2 |

| de Quervain tenosynovitis | 1 to 2 | 20 | 6 | 25 | 1 to 1.5 |

| Trigger finger | 1 | 10 to 20 | 3 | 25 or 27 | 1 to 1.5 |

| Trochanteric bursa | 4 to 6 | 20 | 6 | 22 | 1.5 to 2 |

| Carpal tunnel | 0.5 to 1 | 20 | 3 to 6 | 25 or 27 | 1 to 1.5 |

| Morton neuroma | 1 to 2 | 20 | 3 to 6 | 25 | 1 to 1.5 |

Timing. Corticosteroid injections are appropriate when pain prohibits activities of daily living, leisure activities, or fitness. They may be performed as an adjunct to rehabilitation.25 For patients with knee osteoarthritis, rehabilitation outperforms corticosteroid injections at one year,26 and corticosteroid injection plus rehabilitation provides no greater pain relief than placebo injection plus rehabilitation.27

Corticosteroid injections provide temporary relief from trochanteric bursitis, adhesive capsulitis, de Quervain tenosynovitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and shoulder impingement syndrome.13,14,16,28–30 These injections should not be performed more frequently than every three months because of their association with cartilage loss and tendon damage.11,31–34

HYALURONIC ACID

Indications. Hyaluronic acid, usually used for knee osteoarthritis, has limited evidence of benefit. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense clinical practice guideline issued a weak recommendation for hyaluronic acid.35 The Osteoarthritis Research Society International supports hyaluronic acid use in knee osteoarthritis in patients with comorbid conditions and the general population.36 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons recommends against the routine use of hyaluronic acid.37 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed minimal clinically significant improvement in pain or function and significant adverse reactions with hyaluronic acid knee injections.38 Similarly, the American College of Rheumatology recommends against hyaluronic acid injections for knee osteoarthritis, noting that it can be considered in patients who have not been treated successfully with topical NSAIDs or corticosteroids.39 Another subanalysis found hyaluronic acid beneficial for patients with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis and a body mass index of less than 30 kg per m2.40

Timing. Hyaluronic acid injections are often used in early to moderate knee osteoarthritis, with a peak response at six to eight weeks and less benefit by six months postinjection.41 However, most insurance requires failure of three months of conservative therapy and contraindication to or failure of corticosteroid injections. Hyaluronic acid injections may be single- or multidose. Multidose formulations are commonly performed for consecutive weeks.42

DEXTROSE PROLOTHERAPY

Indications. Prolotherapy is dextrose diluted with anesthetic to yield concentrations of 5% to 25% dextrose and is used as soft tissue treatment in tendinopathy and ligamentous pathology and intra-articularly for degenerative joint pain. A three-injection series of dextrose prolotherapy outperformed saline injections in adults with more than six months of lateral elbow pain refractory to rehabilitation, NSAIDs, and two corticosteroid injections.43 In a case-control study, tendons without tears had a more significant reduction in pain with a series of three prolotherapy injections; however, all tendons (with and without tears) had statistically significant improvements in pain.44 Prolotherapy for common extensor tendinopathy is more effective in patients younger than 45 years and with less than 12 months of pain.44 Dextrose prolotherapy decreases pain and improves function in patients with knee osteoarthritis.45–47

PLATELET-RICH PLASMA

Indications. Although platelet-rich plasma is generally accepted as safe, variability in procedure techniques has resulted in unclear effectiveness and reproducibility in studies. Current evidence does not support the use of platelet-rich plasma in tendinopathies except for common extensor tendinopathy.49,50 Compared with placebo, platelet-rich plasma showed no significant difference in pain or function in Achilles, patellar, and rotator cuff tendinopathy.51–54 Conflicting evidence indicates a possible benefit in plantar fasciopathy.55,56 A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 RCTs of adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis found that compared with hyaluronic acid, saline, ozone, and corticosteroid injections, platelet-rich plasma was more effective at improving pain and function at three, six, and 12 months after injection without increasing adverse events.57 A 2021 meta-analysis of 34 RCTs confirmed the superiority of platelet-rich plasma over other injections for knee osteoarthritis but did not meet the authors' prespecified minimal clinically significant difference.58,59

Preparation

Patient and injection preparation is important for procedural success.4,5 Patient preparation involves a detailed overview of the procedure, informed consent, and proper positioning. The available evidence suggests that washing hands, using nonsterile gloves, and cleansing the skin with alcohol before an injection is safe and inexpensive, with safety outcomes comparable to a sterile technique.61 Table 4 provides a basic supply list.2 Figure 2 provides a visual example of a tray setup for injection. Sterility of injection supplies should be maintained by avoiding direct manipulation of needle and syringe hubs.

| Syringe |

| Needle |

| Alcohol, povidone-iodine, or chlorhexidine swabs |

| Gauze pads |

| Bandage |

| Ethyl chloride spray (optional) |

| Pillow, wedge, other devices for patient comfort and positioning |

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications to soft tissue and joint injections include infection at the injection site, fracture, and a history of a serious allergy to the injection substrate or local anesthetics. Relative contraindications include systemic infection, history of vasovagal reaction, and current anticoagulation therapy.34 Contraindications to platelet-rich plasma injections include coagulopathies, hematologic malignancy, and platelet function disorders.62

Complications

Immediate complications may include pain, swelling, redness, stiffness, or soreness involving the injection site. These reactions can last from a few hours to several days and have been noted in 3% to 25% of patients receiving intra-articular corticosteroids and 2% to 6% of patients receiving intra-articular hyaluronic acid for knee osteoarthritis.11,63 Risk of infection is mitigated by using a clean technique. Patients should be counseled about potential complications and signs and symptoms of infection.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections are associated with transient hyperglycemia that may last a few hours to almost two weeks.64 Patients who have insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus should monitor their blood glucose more frequently to determine if insulin dose adjustments are necessary.64,65

Cartilage damage from corticosteroid injections is time-dependent and dose-dependent.66,67 One study found that repeated treatments (every three months) with intra-articular triamcinolone acetonide contributed to higher rates of cartilage loss and progressive joint space narrowing over two years compared with placebo.31 However, this study does not reflect routine care because patients were treated with corticosteroid injections regardless of symptoms.31,66 A population-based cohort study followed patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis over five years who received intra-articular corticosteroid or hyaluronic acid injections only when symptomatic; there was no significant change in cartilage thickness when corticosteroid injections were used only for symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis flare-ups.67

Corticosteroid injections into soft tissue can cause depigmentation and atrophy, which usually develop days to weeks following injection.11,34 Inaccurate placement of the needle and injectate can lead to injury of adjacent structures and potential tendon trauma.3 Plantar fascia rupture and heel pad atrophy are rare complications associated with corticosteroid injections for plantar fasciitis.

Most injections administered in the primary care office are performed by palpation of landmarks to determine the placement of the injectate. The use of imaging guidance, such as ultrasonography, may increase the accuracy of needle placement and is recommended for specific anatomic locations.3

Joint and soft tissue injections are useful adjuncts for diagnosing and treating common musculoskeletal conditions. However, there are times when injection in the primary care office may not be appropriate. Table 5 lists indications for referral to primary care sports medicine, orthopedic surgery, or pain medicine.8–10

| Desired injectate unavailable |

| Family physician is untrained in procedure |

| Image-guidance required |

| Nerve hydrodissections |

| Specific anatomic locations: glenohumeral joint, acromioclavicular joint, biceps tendon sheath, femoro-acetabular joint |

| Patient-oriented response not achieved after intervention by family physician |

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Cardone and Tallia.2

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms injection, tendinopathy, tendinitis, degenerative, joint, and osteoarthritis. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality were also searched. Search dates: September 11, 2022, and May 30, 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.