Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(2):166-174

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Pressure injuries are localized damage to skin or soft tissue. They commonly occur over bony prominences and often present as an intact or open wound. Pressure injuries are common and costly, and they significantly impact patient quality of life. Comprehensive skin assessments are crucial for evaluating pressure injuries. Staging of pressure injuries should follow the updated staging system of the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Risk assessments allow for appropriate prevention and care planning, and physicians should use a structured, repeatable approach. Prevention of pressure injuries focuses on assessing and optimizing nutritional status, repositioning the patient, and providing appropriate support surfaces. Treatment involves pressure off-loading, nutritional optimization, appropriate bandage selection, and wound site management. Pressure injuries and surrounding areas should be cleaned, with additional debridement of devitalized tissue and biofilm if necessary. All injuries should be monitored for local infection, biofilms, and osteomyelitis. Appropriate wound dressings should be selected based on injury stage and the quality and volume of exudate.

Pressure injuries are focal damage to skin, underlying tissue, or mucous membranes resulting from pressure that is intense, prolonged, or both. The combination of pressure and shear forces can also cause pressure injuries.1 Bony prominences are common sites for pressure injuries. These injuries can also be related to medical devices or other objects that come in contact with the patient's skin. The term pressure injury is recommended, although these injuries are also known as pressure ulcers, decubitus ulcers, pressure sores, or bed sores.1–3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| A structured, repeatable approach, including risk assessment tools, should be used to identify patients at risk of pressure injuries.1,10,17 | C | Consensus guidelines |

| Skin examinations for high-risk individuals should include skin integrity, erythema, firmness, moisture, pain, and variations in heat.1,10 | C | Consensus guidelines |

| High-specification foam mattresses are more beneficial than regular foam mattresses for individuals at risk of pressure injuries.1,10,27 | B | Consensus guidelines and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| Hydrocolloid, calcium alginate, or foam dressings should be used for the treatment of pressure injuries with exudate. Hydrogel dressings are most appropriate for injuries with minimal exudate.1,41 | C | Consensus guidelines |

Epidemiology

More than 3 million pressure injuries are treated in the United States each year.4,5 Stage 1 and 2 pressure injuries are most prevalent.6 Longitudinal studies have shown a decline in the incidence of pressure injuries over the past two decades, which could be related to increased clinical attention or changes in definitions or populations.7 Hospital-associated pressure injuries are estimated to cost the U.S. health care system $26.8 billion annually, with costs disproportionately associated with more advanced stages of injury.8

Evaluation

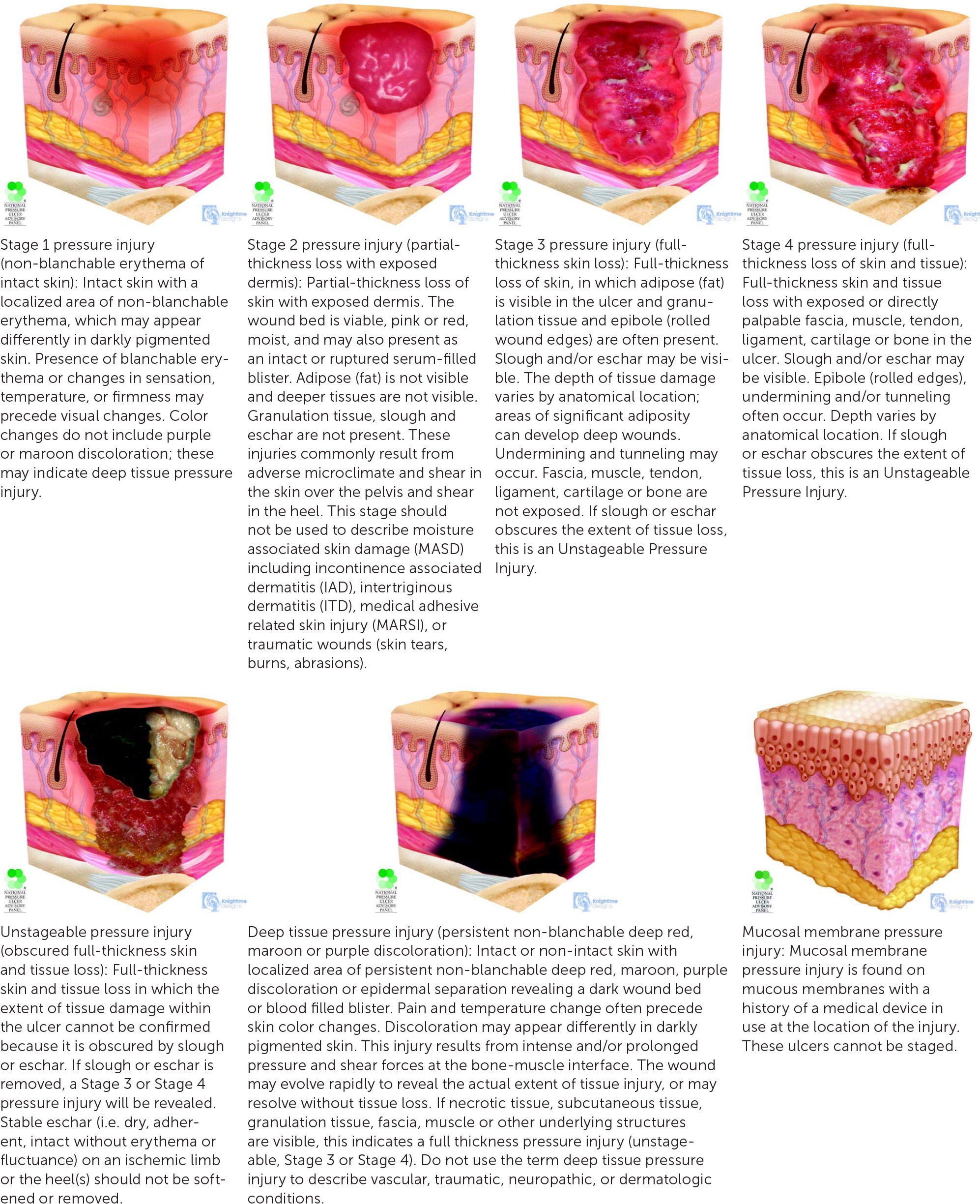

Staging of a pressure injury should use the updated National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) staging system (Figure 1).9 Notable changes from previous iterations include limiting the use of the term ulcer to only injuries featuring breaks in the skin and expanding injury types to include those caused by medical or other devices.3 Medical device–related pressure injuries result from a device in direct contact with a patient. It is important to consider the contributory device, but the injury should also be defined by the staging system.1 Pressure injuries can occur on mucosal linings of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or genitourinary tracts. Due to the locations of these injuries, they cannot be staged.3

Risk Assessment

Assessing for risk factors is crucial to ensure appropriate prevention and plan of care. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines and those developed jointly by the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), NPIAP, and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA) recommend a comprehensive clinical assessment for any risk factors central to the pathophysiology of pressure injury development, such as sensory loss, malnutrition, inactivity, immobility, and reduced perfusion.1,10

The risk assessment should focus on factors that influence the magnitude, type, and duration of pressure, as well as patient-specific factors that impact individual tolerance and susceptibility to injury 1,11 (Table 11,12,13). Reduced activity (ability to complete activities of daily living) and mobility (ability to change or control physical position) increase mechanical load and are consistently associated with the development of pressure injuries.1,12

| Age Neonates and children (because of limited mobility, lack of skin maturity, relatively larger skin surface area and larger head circumference, and higher risk of nutritional deficiencies) Older adults Increased body temperature Limited mobility In hospice or palliative care Increased immobilization perioperatively Obesity Progressive neurologic conditions (multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease) Spinal cord injury Stroke | Medical comorbidities Congestive heart failure Dementia (e.g., vascular, Alzheimer) Diabetes mellitus Peripheral vascular disease Medical device or prosthesis use Moisture Bowel or bladder incontinence Increased perspiration Wound drainage Personal history of pressure injuries or current Stage 1 pressure injury Poor nutrition or malnutrition Prolonged stay at a nursing home or rehabilitation facility |

Preexisting pressure injuries, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease, and impaired circulation can further increase risk. Increased moisture from urine, stool, and sweat can cause skin maceration and escalate the risk of pressure injuries. The patient's external environment, such as hard surfaces on prostheses, shear forces from wheelchair use, or uneven sleeping surfaces, can further compound risk.

Particular attention should be placed on populations at higher risk of pressure injuries, including people who are critically ill; individuals with spinal cord injuries or other immobility conditions; people receiving palliative care; acutely ill and immobilized neonates and children; people with obesity; people in the preoperative period; and people in the community receiving care for advanced age or requiring facility rehabilitation services due to mobility limitations.1,10,14,15

A comprehensive skin assessment is critical for patients at higher risk of pressure injuries and should be completed immediately at inpatient admission and then periodically depending on illness acuity or change in the patient's condition. The assessment should focus on areas overlying bony prominences or in contact with medical devices, especially breathing devices, tubes, splints, intravenous catheters, and cervical support collars.1,16

This assessment should note skin integrity, blanchable or nonblanchable erythema, firmness, moisture, any pain or discomfort, and variations in heat.10 If an injury is identified, documentation should include injury onset, progression, base qualities, presence of drainage or odor, prior treatments, and measurements such as depth. Images of injuries can be added to the electronic health record for initial documentation and assessment of injury progression.

Clinical guidelines recommend a structured, repeatable approach to evaluating risk of pressure injuries in conjunction with a comprehensive skin examination and clinical judgment.1,10,17 Risk assessment tools such as the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10038/braden-score-pressure-ulcers) and the Norton Scale (https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/hospital/resource/pressureulcer/tool) are often used.18,19 Although many algorithms have been validated, their sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients at risk of pressure injuries are low.4,17 Despite the prevalent use of risk assessment tools, there is no evidence of reduced pressure injuries associated with any scale.4,20 EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA guidelines and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality best practices recommend an initial assessment on hospital admission, with reassessments depending on illness acuity and the specific care setting, although a paucity of evidence limits specific recommendations.1,21

Prevention

Interventions to prevent pressure injuries should be initiated for patients at elevated risk. The EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA guidelines recommend implementing a skin care regimen to keep the skin hydrated and clean (particularly following incontinence events), using moisture barriers, and avoiding alkaline soaps and cleansers (e.g., standard hospital soap with a pH of 9.5 to 10.5) in favor of a balanced cleanser with a pH of 5.5.1,22,23

Nutritional assessment and support are also important in pressure injury prevention. Weight loss can increase the risk of pressure injuries.24 Nutritional screening tools and assessments (including the Nutrition Risk Screening Tool [https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/4012/nutrition-risk-screening-2002-nrs-2002] and the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool [https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10190/malnutrition-universal-screening-tool-must]) can identify individuals at risk of malnutrition and assist in developing a plan to optimize calorie and protein intake. However, use of nutritional screening tools has limited effectiveness in preventing pressure injuries.4,25 Additional information on nutritional support therapy is available in a previous issue of American Family Physician (AFP).26

Additionally, repositioning and mobilization plans should be individualized to each patient. Changes in weight, body habitus, or functional status require appropriate modifications in the use of beds, chairs, or prostheses. Individuals at risk of pressure injuries should be encouraged to change positions often, with assistance if necessary.10 The frequency of positional changes should be guided by clinical judgment and individualized to the patient's activity and mobility levels.1 Auditory or visual reminders can be used to increase adherence to repositioning schedules.1 The EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA guidelines recommend early mobilization, angling wheel-chair seats to reduce sliding, using manual handling techniques or equipment for repositioning to limit shear forces, and making the head of the patient's bed as level as possible.1

Support surfaces can be static or dynamic. Static surfaces, such as standard hospital foam mattresses and hospital pillows, do not provide intermittent off-loading.1 High-specification foam mattresses and medical-grade sheepskin surfaces are more beneficial than regular foam mattresses.10,27 Foam mattress surfaces may increase the incidence of pressure injury compared with alternating pressure or reactive air surfaces and may be less cost-effective.28 Advanced static mattresses or overlays, made of materials such as gel-infused memory foam, should be used for patients with increased risk.17 Dynamic surfaces, such as alternating pressure mattresses, can off-load high pressure areas without caregiver engagement. However, evidence on the surfaces used to prevent injuries is mixed and insufficient to support clear recommendations.29

Ensuring appropriate caregiver and family education on preventive measures is important to improve caregiver comfort and understanding, although existing data indicate that educational programs do not have a significant effect on preventing pressure injuries.30

General Management

Following identification of a pressure injury, a comprehensive examination (including social and medical history) should be performed. The physical examination should document the location and size of the injury; associated pain; presence of exudate, sloughing, undermining, or tunneling; wound bed color; and integrity of the surrounding skin.31 The etiology of pressure injuries is multifactorial and often coincides with complicated systemic comorbidities; thus, effective management involves an interdisciplinary team that includes caregivers.

It is critical to regularly evaluate healing progression, status of dressings and surrounding skin, adequacy of pain control, and presence of potential complications. Healing assessment tools, including the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing; DESIGN-R (depth, exudates, size, inflammation/infection, granulation, necrosis, rating) tool; and Bates-Jensen Wound Assessment Tool can be used to monitor healing.1

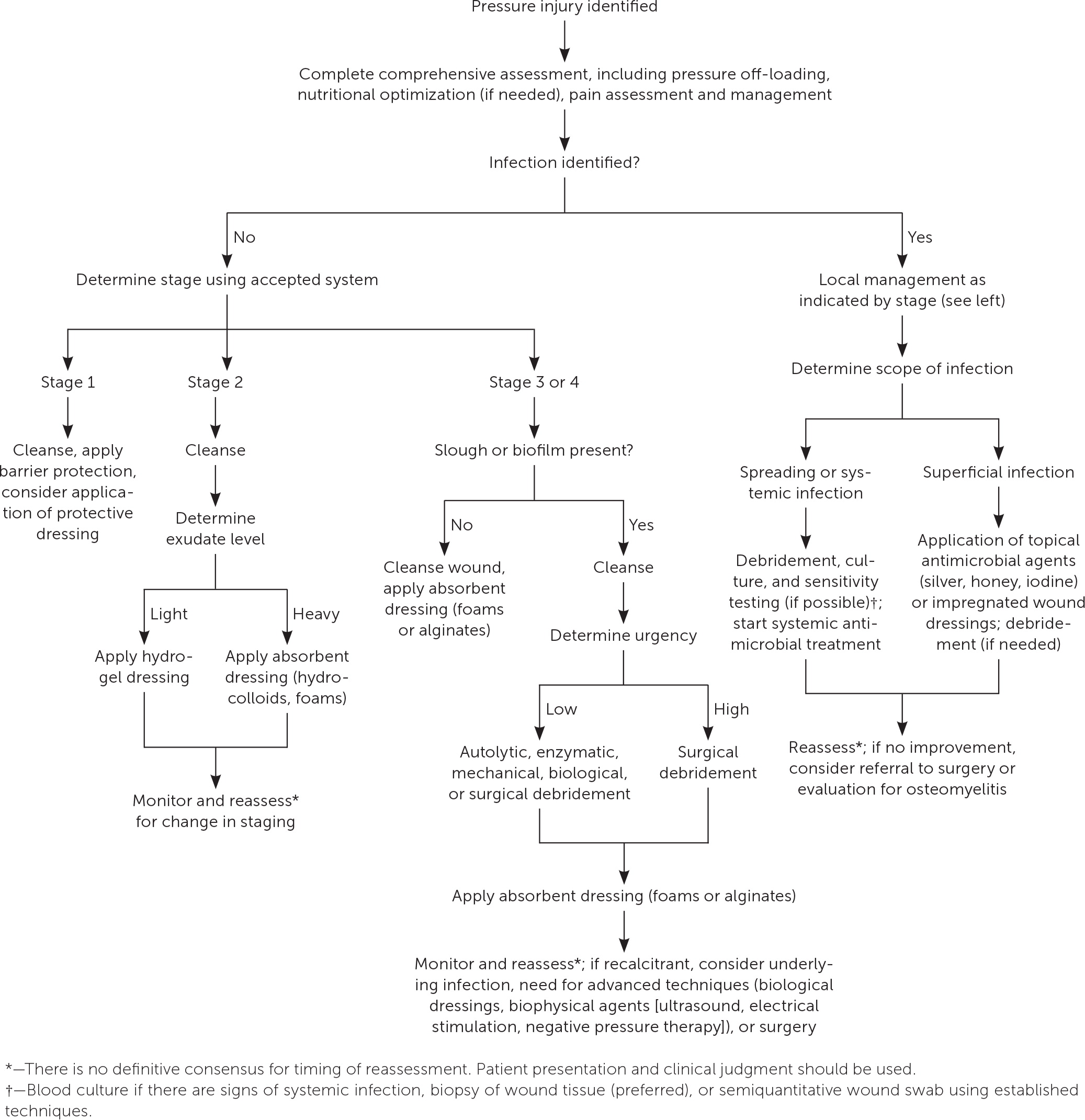

Management of pressure injuries involves pressure off-loading, nutritional optimization, and wound site management (Figure 2).1,13 Wound site management includes debridement, skin care, control of microbial virulence and burden, and bandage selection (Table 2).1,32 Smoking cessation should be facilitated, if applicable. Treatment plans should account for the psychosocial trauma that pressure injuries may cause patients and caregivers. Provision of psychosocial support can improve adherence to treatment plans.33 Caregiver education may be beneficial for identifying changes in the wound and associated pain. Pain should be adequately addressed, especially during wound cleaning, debridement, repositioning, and dressing changes.1

| Dressing | Injury type | Guidance for use | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Add moisture | |||

| Hydrogels | Noninfected Stage 2 injuries with minimal drainage | Preferred for dry wound beds that would benefit from autolytic debridement; barrier protection may be added around wound to reduce risk of maceration | Intrasite, Duoderm, Derma-Gel, Allevyn Hydrogel, cellulose fiber dressings |

| Moist gauze | Alternative dressing for any injury type | Use when other wound dressing types are not an option; associated with slower wound healing; costly in professional time, as frequent visits for dressing changes are needed; can damage wound bed; use of impregnated gauze should be considered | Kerlix, Curity |

| Retain moisture | |||

| Films | Secondary dressing for any injury type | Avoid use over enzymatic debriding agents | Carrafilm, Opsite, Uniflex, 3M Tegaderm |

| Remove moisture | |||

| Calcium alginate | Stage 3 and 4 injuries with moderate exudate | Avoid use in dry wound beds; can maintain a physiologic environment | Curasorb, Algisite M, Algicell, Carrasorb |

| Foams | Stage 2 and greater pressure injuries with moderate or heavy exudate | Use in deep injuries, with additional use of filler dressings to occupy empty space; requires secondary dressing to extend duration of use | Allevyn, Curafoam, Lyofoam, Mepilex, Tielle |

| Hydrocolloids | Noninfected Stage 2 injuries | Must be removed carefully from fragile skin because removal can cause trauma; does not require frequent dressing changes | Tegasorb, Hydrocol, 3M Tegaderm, Hollister Restore, Duoderm, Comfeel |

| Antimicrobial agents* | |||

| Calcium alginate gels | Injuries with or at risk of biofilms | Prevents and destroys biofilms | Dermaginate, Tegaderm Alginate |

| Honey | Injuries with or at risk of biofilms | Prevents biofilm growth and extension of colonization; honey made with Leptospermum species is most effective; medical-grade, gamma-irradiated product should be used | Medihoney, Activon Tulle Honey, Dynarex L-Mesitran |

| Iodine | Injuries with or at risk of biofilms | Prevents biofilm growth and destroys active biofilms; avoid in patients with iodine allergies or kidney and thyroid dysfunction; contraindicated for extensive burns | Iodoflex, Inadine |

| Wound dressings impregnated with silver salts or metals | Injuries with or at risk of biofilms | Breaks down active biofilm; avoid in patients with silver sensitivity; must be changed more often if there is heavy exudate | Aquacel Ag, Silvercel, Mepilex Ag |

| Surfactant | Injuries with or at risk of biofilms | Prevents biofilm development and improves effectiveness of antibiotics; may require initial daily application | Plurogel |

Although data are limited, expert opinion recommends use of nonpharmacologic interventions to address pain. Examples include educating patients and caregivers about expectations during repositioning or bedside procedures; addressing psychosocial stress; and using heat, progressive relaxation, and centering and music therapies.1 Smaller studies have shown that topical opioid analgesics can also be used to manage pressure injury pain.1,34,35 Pharmacologic strategies to manage acute pain were discussed previously in AFP.36

PRESSURE OFF-LOADING

Pressure off-loading focuses on the specific location affected by a pressure injury. Although evidence supporting pressure off-loading protocols for treatment is limited, expert opinion supports the use of repositioning to optimize healing while taking care to avoid reciprocal injuries.1,37,38 The ideal frequency of positional shifts is not clearly defined,38,39 but routine repositioning is recommended to avoid injury progression or the development of subsequent pressure injuries.1 It is unclear whether certain support surfaces or bed types (e.g., foam, gel, water) improve healing of pressure injuries.40 Specialized support to ensure appropriate pressure off-loading is recommended, although costs and patient preferences should also be considered in the absence of evidence-based protocols. If injuries develop from use of medical devices, recalibration and refitting should be completed promptly. Individuals with or at risk of heel pressure injuries should use a heel-specific suspension device or other mechanism, such as placing a pillow under the legs, to offload heel pressure1; see the example.

NUTRITIONAL OPTIMIZATION

Nutritional supplementation may improve wound healing; however, data regarding specific interventions are mixed.25,41 Additional information can be found in a previous AFP article on chronic wounds.42 If patients are malnourished or at risk of malnourishment, the EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA guidelines recommend daily supplementation with 1.25 to 1.5 g of protein per kg of body weight and 30 to 35 kcal per kg of body weight.1 Physicians should encourage adequate hydration for patients with pressure injuries when it is compatible with goals of care and clinical condition.1 Micronutrient (e.g., zinc, arginine, vitamin C) supplementation may assist in healing; however, data are inconclusive regarding the benefits in patients without existing nutritional deficiencies.25,43

Wound Site Management

CLEANSING AND DEBRIDEMENT

Pressure injuries should be cleansed to remove debris and promote healing without damaging healthy tissue.1 Removing devitalized tissue and microfilms and draining abscesses can facilitate wound healing. Specific debridement techniques vary and depend on wound characteristics, such as the presence of slough and biofilm. Common forms of debridement use pressure or surgical, mechanical, enzymatic, autolytic, or biological methods. Slough on heels or ischemic limbs that is fixed, firm, or dry should not be debrided unless there is a high suspicion for infection.1

SKIN CARE

Appropriate care of healthy skin surrounding a pressure injury can prevent injury progression and support healing. Healthy skin can be protected from moisture and irritation caused by wound drainage, sweat, urine, and stool by using wound dressings or emollients (e.g., petroleum gel, zinc oxide) as barriers.1 Urinary catheters, rectal tubes, and a diverting colostomy can be used to avoid exposure to skin irritants, but these interventions should be implemented with caution in the absence of clear evidence supporting a clinical benefit.

MICROBIAL MITIGATION

Damage to epithelial barriers and inhibition of local immune function increase the risk of bacterial growth. Infection can be considered on a continuum from contamination, to colonization, to local infection, which can potentially spread and become systemic.44 Signs of infection include delayed healing, dehiscence, necrotic tissue, warmth, or increased exudate at the wound site, or the patient experiencing fever, confusion, or pain.1 Osteomyelitis should be suspected if bone is visible or if healing has not occurred despite appropriate treatment, and it can be confirmed with a bone biopsy or magnetic resonance imaging.

Routine use of topical antiseptics is not recommended, but they may be used to control microbial burden.1,10 Colonization or infection is often polymicrobial, with a wide range of possible bacteria depending on the geographic and clinical settings, although some data show that Staphylococcus aureus is prevalent in hospital-based infections.1 Systemic antibiotics should be used judiciously in the setting of positive blood culture results, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or sepsis.1 Although topical antiseptics are often used, data are limited and relative effects on treatment are unclear.45

ADJUNCTIVE AND EMERGING THERAPIES

Guidelines recommend electrical stimulation to assist wound healing in higher stage injuries with delayed healing.1,41 However, a Cochrane review notes that data are insufficient to recommend widespread use outside of research.46 Ultrasound (high-frequency or noncontact, low-frequency) can be used for Stage 3 or 4 pressure injuries to supplement other treatments.1 Negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum-assisted closure can be used adjunctively for early Stage 3 or 4 injuries to reduce the size of wounds, particularly in patients with spinal cord injuries.1,47 However, data are limited,48 and costs are significant. Biological dressings are being investigated to assist in healing of pressure injuries. Collagen matrix dressings (sheets or pads made from bovine, porcine, or avian skin) can improve healing and reduce inflammation in nonhealing injuries but are limited by cost and availability compared with traditional dressings.1

BANDAGE SELECTION

Bandage selection should be optimized for wound characteristics while considering patient preference, insurance coverage, caregiver skill, and local availability of supplies.

Increased moisture can create an environment amenable to bacterial colonization and requires absorptive bandages, including gelling cellulose fiber dressing or gauze, and hydrocolloids for Stage 2 injuries or calcium alginate dressings for Stage 3 and 4 injuries.1,41 Foam dressings can be used for Stage 2 and greater injuries with moderate to heavy exudate.1 Hydrocolloid, calcium alginate, or foam dressings should be used for the treatment of pressure injuries with exudate. Hydrogel dressings are most appropriate for injuries with minimal exudate.1,41

Absorptive bandages require frequent changes to remove excess fluid. Dry wound beds require bandages that provide a moist environment. Films are semipermeable and help retain moisture, whereas hydrogels add moisture to the wound bed. In cases of wound tunneling or undermining, dead space should be packed loosely with moist gauze or strips of calcium alginate. If there is concern for infection, antimicrobial dressings or ointments can be considered.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Bluestein and Javaheri,13 and Raetz and Wick.49

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms pressure ulcer and pressure injury. The search included meta-analyses, reviews, and systematic reviews. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, UpToDate, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports. Search dates: August 27, 2022, and April 22, 2023.