Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(2):175-180

Patient information: See related handout on evaluating acute pelvic pain.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Acute pelvic pain is defined as noncyclic, intense pain localized to the lower abdomen and/or pelvis, with a duration of less than three months. Signs and symptoms are often nonspecific. The differential diagnosis is broad, based on the patient's age and pregnancy status and gynecologic vs. nongynecologic etiology. Nongynecologic etiologies include gastrointestinal, urinary, and musculoskeletal conditions. Urgent gynecologic conditions include ectopic pregnancy, ruptured ovarian cyst, adnexal torsion, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Approximately 40% of ectopic pregnancies are misdiagnosed at the presenting visit. Urgent nongynecologic conditions include appendicitis and pyelonephritis. Less urgent etiologies include sexually transmitted infections, pelvic floor myofascial pain, dysmenorrhea, and muscle strain. Approximately 15% of untreated chlamydia infections lead to pelvic inflammatory disease. History and physical examination findings guide laboratory testing. Questions should focus on the type, onset, location, and radiation of pain; timing and duration of symptoms; aggravating and relieving factors; and associated symptoms. Performing a urine pregnancy test or beta human chorionic gonadotropin test is an important first step for sexually active, premenopausal patients. Imaging options should be considered, with transvaginal ultrasonography first, followed by computed tomography. Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful if ultrasonography and computed tomography are nondiagnostic.

Acute pelvic pain is a common presentation defined as noncyclic, intense pain localized to the lower abdomen and/or pelvis, with a duration of less than three months.1–3 Diagnosis is challenging because the differential diagnosis is broad, and signs and symptoms are often nonspecific and vary across etiologies.

Although many etiologies of pelvic pain are non–life-threatening, life- and fertility-threatening diagnoses should be considered. A retrospective review of pregnancies from 2006 to 2013 showed that 8.3 of 1,000 pregnancies were ectopic, a condition responsible for 6% of maternal deaths.4,5 Adnexal torsion represents approximately 3% of abdominal pain cases in women.5 Appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency, with an incidence of 100 cases per 100,000 patients per year.6

This article provides an approach to the evaluation of acute pelvic pain in patients with natal female anatomy. Acute abdominal pain in a patient with known intrauterine pregnancy is beyond the scope of this article.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute pelvic pain in women encompasses a broad differential diagnosis spanning multiple organ systems. The patient's pregnancy status should be assessed first, followed by stratification of presenting symptoms into gynecologic vs. nongynecologic etiologies. Symptoms can be further stratified by organ system, including reproductive, gastrointestinal, urinary, and musculoskeletal.

Gynecologic causes are common in patients with acute pelvic pain.7 Urgent evaluation for ectopic pregnancy, ruptured ovarian cyst, adnexal torsion, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is important.2,3,8 Approximately 40% of ectopic pregnancies are misdiagnosed at the presenting visit.9 PID is underdiagnosed and undertreated, with significant sequelae.8 Approximately 15% of untreated chlamydial infections lead to PID.8

Less urgent etiologies of pelvic pain in women include pelvic floor myofascial pain, dysmenorrhea, vaginal atrophy, vaginismus and dyspareunia, muscle strain, and abdominal wall pain.10–12 Patients undergoing fertility treatment can have ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome with enlarged ovaries and multiple follicular cysts.7

Gastrointestinal etiologies of pelvic pain in women include appendicitis (most common), diverticulitis, volvulus, and epiploic appendagitis.7,13 Musculoskeletal etiologies include muscle strain, tendinopathy, hernia of the abdominal musculature, abdominal wall pain, and abdominal nerve entrapment. Urinary etiologies include urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, and urolithiasis. Other diagnoses to consider in patients with pelvic pain include physical and sexual abuse, trauma, psychogenic causes, and vascular etiologies such as aortic or iliac artery dissection or rupture and thrombosis of the iliac, mesenteric, or ovarian veins.7

History

History findings can guide the physical examination, laboratory studies, imaging, and management. Questions should focus on the quality, onset, location, and radiation of pain; timing and duration of symptoms; and aggravating and relieving factors.2

A review of the patient's medical history should include episodes of similar symptoms, gynecologic conditions, and surgeries of the relevant organ systems. A social history should include sexual history (e.g., sexually transmitted infections, sex partners), sexual abuse, use of contraceptives, pregnancies, age of menarche, last menstrual period, number of bleeding days, and use of menstrual products.1,2,14,15

Physical Examination

The physical examination should focus on the patient's vital signs and examination of the abdomen and pelvis (Table 12,3,7,8,14,16–21). Assessing for unilateral abdominal pain, pain over the McBurney point, and a positive Rovsing sign (pain in the right lower quadrant with palpation over the left lower quadrant) can be helpful in distinguishing appendicitis from PID, which is often more diffuse and bilateral.13 Assessing for the Carnett sign is helpful to delineate abdominal wall etiologies.17 For this assessment, pain is evaluated as the patient contracts the abdominal wall muscles. Worsening of pain suggests it is associated with the abdominal wall or musculature.17,18

A pelvic examination should be performed while maintaining the patient's dignity and sense of control as much as possible. Although a dorsal lithotomy position with stirrups is most commonly used, alternate positioning, such as dorsal lithotomy without stirrups or lateral positioning with one leg abducted, can be considered for comfort.22,23 The examination should include assessment for abnormalities of the vagina or cervix, pelvic floor defects (e.g., cystocele, rectocele, enterocele), and mucopurulent cervical discharge.8 Bimanual examination can evaluate for cervical motion tenderness, uterine size and contour, and uterine or adnexal masses or tenderness. Cervical motion or adnexal tenderness suggests PID.8 Imperforate hymen, in which a thin membrane of stratified squamous epithelium obstructs the vaginal introitus, can lead to hematocolpos or hematometra, causing accumulation of menstrual blood or tissue in the vagina or uterine cavities and subsequent pelvic pain.24

Laboratory Testing

A urine pregnancy test or beta human chorionic gonadotropin test is an important first step for any patient who could be pregnant.25 These tests are typically positive three to four days after implantation. At seven days past the expected menstrual period, 98% of tests will be positive in those who are pregnant, especially for women with regular menstrual cycles.25

Urinalysis of a midstream urine specimen should be considered to assess for urinary tract infection. Urine culture is often beneficial to confirm suspected urinary tract infection, identify specific organisms, and guide antibiotic use. If testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia, first-void urine collected without cleaning of the urethra (“dirty” catch) has historically been recommended, often requiring two urine samples for full evaluation.26 Logistically this can be challenging. One study found that a midstream sample for chlamydia testing is still 96% accurate, and another study found a sensitivity of 86.2% for chlamydia and 94.4% for gonorrhea. This shows noninferiority to a dirty catch; therefore, one urine sample may be sufficient.26,27

Swab samples can be collected during pelvic examination to test for gonorrhea, chlamydia, bacterial vaginosis, trichomonas, and yeast infection. Potassium hydroxide and saline preparations can be used to further assess vaginal discharge under microscopy.8 Based on the history and examination, other laboratory tests can be considered, including complete blood count, inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein), blood cultures, stool studies (fecal calprotectin, fecal occult blood), and Rh blood typing (if pregnant or if blood transfusion is anticipated).14,15

Imaging

The initial imaging modality of choice for pelvic pain is transvaginal ultrasonography, given its availability, portability, and lack of radiation.1,2,5,28,29 Ultrasonography is sensitive for urgent conditions, including ectopic pregnancy, hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, adnexal torsion, and tubo-ovarian abscess. Transabdominal and Doppler ultrasonography may be used for gynecologic concerns based on the situation and availability.3,28 The sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy ranges from 73% to 93%, depending on gestational age and operator expertise.5 Although PID is a clinical diagnosis, advanced infection may demonstrate tubo-ovarian abscess or pyosalpinx.

Pregnancy should be ruled out before the use of computed tomography (CT) unless the clinical indications are specific and clear, and the risks are discussed with the patient.3 CT has poor soft-tissue contrast of the pelvic reproductive organs, but it is the best option for suspected urinary or gastrointestinal etiologies.7

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be performed if ultrasonography and CT are nondiagnostic.3,7 Further, for women of childbearing age with suspected infection, MRI is the best imaging modality, showing greater soft-tissue resolution.21,28 If imaging is nondiagnostic, laparoscopy should be considered if there is high suspicion for adnexal torsion.5

Appendicitis, a common cause of nongynecologic pelvic pain, can be difficult to diagnose. Ultrasonography should be considered as a low-risk first imaging modality to evaluate for possible appendicitis.19 Per the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria, if ultra-sonography is inconclusive, contrast-enhanced CT or contrast-enhanced MRI can be performed.30 If ultrasonography cannot be performed or is inconclusive, CT is 85.7% to 100% sensitive and 94.8% to 100% specific for the diagnosis of appendicitis and an excellent imaging modality for investigating gastrointestinal etiologies.30 Laparoscopy can confirm appendicitis when suspicion is high and imaging is nondiagnostic.6

Special Populations

EARLY PREGNANCY

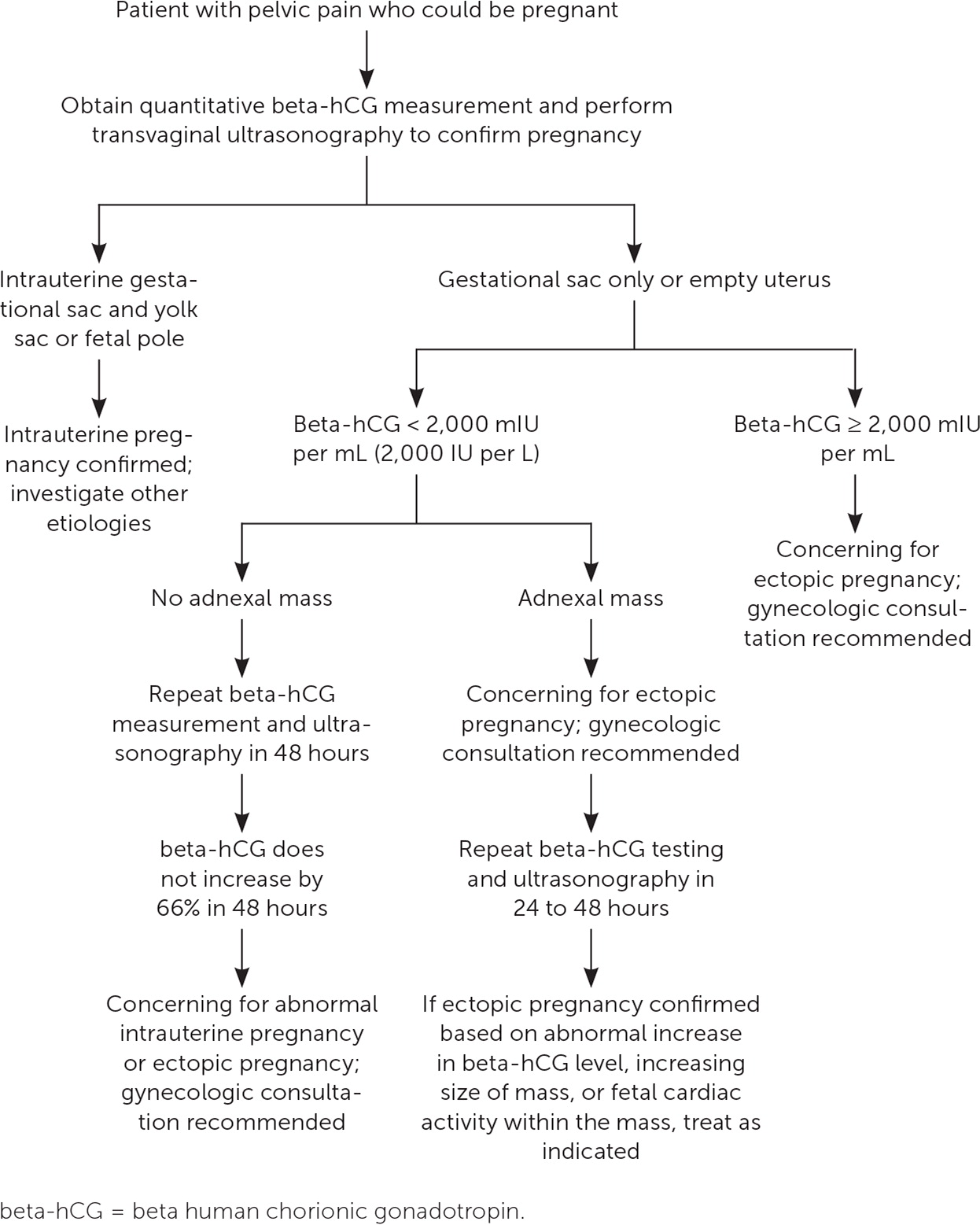

If a pregnancy test result is positive, transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed immediately to confirm the location of the pregnancy. A positive pregnancy test result with no demonstrated intrauterine pregnancy is assumed to be ectopic until proven otherwise.16 Up to 60% of ectopic pregnancies are identified as a nonhomogenous mass separate from the ovary, 20% present with a hyperechoic ring, and 13% present with an obvious gestational sac.16 Nonviable pregnancies, including anembryonic gestation (e.g., enlarged gestational sac with no visualization of a fetal pole) or embryonic demise (sufficiently sized fetal pole with no cardiac activity), may also be noted.16 MRI may be used if there is diagnostic uncertainty.3 Gadolinium-based contrast agents are contraindicated in pregnancy.31

POSTPARTUM

A history should review delivery details such as duration of labor, type of delivery (spontaneous vaginal, operative vaginal, cesarean), use of peripartum antibiotics, and frequency of cervical checks.32,33 Perineal trauma is a common cause of postpartum pelvic pain.33 Endometritis should be considered in patients with fever, especially with associated uterine tenderness, purulent or foul-smelling discharge, and leukocytosis.34,35 Urinary tract infections are also common post-partum. Risks of endometritis and urinary tract infection increase with increased labor duration, number of cervical checks, and use of forceps or vacuum.32

ADOLESCENTS

Sexual history, including abuse, might play a role in the presentation of acute pelvic pain. Sexual abuse should be considered in this population, given that one study reported that approximately 1 in 4 girls is sexually abused by 17 years of age.38 Forensic examination and management of sexually transmitted infection or pregnancy can be considered, if warranted based on history.38

POSTMENOPAUSE

Approximately 15% of acute pelvic pain occurs in postmenopausal patients. The differential diagnosis is similar to that of premenopausal patients, with common etiologies including vaginal atrophy, ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, and PID. However, the risk of ovarian cancer is greater in older women.39 Malignancy must be ruled out in postmenopausal patients with acute pelvic pain and associated bleeding.7

Ultrasonography is the initial imaging modality in postmenopausal patients, with consideration of transvaginal or transabdominal ultrasonography based on history and physical examination findings.7,11 Vaginal atrophy is common in postmenopausal patients secondary to decreased estrogen, making the epithelium thin, friable, and dry and causing pain during penetrative intercourse.12

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Bhavsar and Gelner,14 and Kruszka and Kruszka.15

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms acute pelvic pain, female, and abnormal uterine bleeding. Further specifiers included adolescent, pregnant, postpartum, postmenopausal, ultrasound, and imaging. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and clinical reviews. We also searched Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Health Care Reports, the Cochrane database, DynaMed, and Essential Evidence Plus. Studies reviewed included patients with natal female anatomy. Search dates: November 18, 2021; March 20, 2022; August through October 2022; January and February 2023; and July 14, 2023.