Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(2):181-188

Patient information: See related handout on speech and language delay in children.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Childhood speech and language concerns are commonly encountered in the primary care setting. Family physicians are integral in the identification and initial evaluation of children with speech and language delays. Parental concerns and observations and milestone assessment aid in the identification of speech and language abnormalities. Concerning presentations at 24 months or older include speaking fewer than 50 words, incomprehensible speech, and notable speech and language deficits on age-specific testing. Validated screening tools that rely on parental reporting can serve as practical adjuncts during clinic evaluation. Early referral for additional evaluation can mitigate the development of long-term communication disorders and adverse effects on social and academic development. All children who have concerns for speech and language delays should be referred to speech language pathology and audiology for diagnostic and management purposes. Parents and caretakers may also self-refer to early intervention programs for evaluation and management of speech and language concerns in children younger than three years.

Speech is the verbal production of language. Language is the processing of a communication system. Receptive language includes an individual's comprehension abilities. Expressive language includes conveying ideas in spoken, written, or visual forms.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental surveillance should be completed at every well-child visit until at least five years of age.3 | C | American Academy of Pediatrics consensus report that summarized findings from 24 studies to determine accuracy of screening tools; no studies met inclusion criteria for investigating improved outcomes with screening |

| For abnormal speech and language developmental screening findings, immediate referral is recommended rather than following conservatively.3,26 | C | Studies demonstrating that late talkers either have a language impairment or further delayed-language accession |

| Early identification and treatment of speech and language delays are recommended to avoid long-term negative impacts on social development and school performance.3,22 | C | American Academy of Pediatrics consensus report that summarized findings from 13 randomized control trials and one systematic review of speech and language outcomes from treatment. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association medical review guidelines |

| Universal hearing screening should be completed after birth; at four, five, six, eight, and 10 years of age; and once between 11 and 14, 15 and 17, and 18 and 21 years of age.27 | C | American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures recommendation |

Speech delays stem from difficulty with speech or language processing or both. Speech and language delays usually result in the ultimate achievement of normal skills but at a slower rate than expected.2 Family physicians play an important role in prompt identification of speech and language delays to mitigate the development of communication disorders, which hinder a child's development with long-lasting adverse social and academic impacts.

Speech and Language Development

Distinct milestones mark development by age (Table 1).3,4 Early speech includes sounds, such as cooing and babbling, and later incorporates word combinations that lead to full sentences. Language development begins with basic comprehension that builds to advanced language skills, including the expression of complex thoughts. Evidence suggests that critical language development occurs in the first six months of life5 and that early childhood language exposure significantly influences a child's language mastery.3

| Age | Receptive | Expressive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two months | Calms or smiles when presented with verbal and gestural cues Reacts to loud noises | Makes sounds in addition to crying | |

| Four months | Responds to verbal cues with sounds Turns head to sound of parent's voice | Makes cooing sounds Chuckles (not yet laughter) | |

| Six months | Responds to verbal cues by taking turns making sounds with others | Laughs Blows “raspberries” Squeals | |

| Nine months | Looks when name is called | Makes consonant sounds Lifts arms to be picked up | |

| 12 months | Understands “no” | Waves “bye-bye” Uses specific names for parents, such as mama, dada, or another special name | |

| 15 months | Looks at a familiar object when mentioned Follows one-step directions given with gestures and words | Tries to say one or two words besides mama or dada Points to ask for something or to get help | |

| 18 months | Follows one-step directions without gestures | Tries to say at least three words other than mama or dada | |

| 24 months | When prompted: Points to items in a book Points to two body parts | Says two-word phrases Uses gestures besides waving and pointing (e.g., blowing kiss, nodding “yes”) | |

| 30 months | Follows two-step directions Follows simple routines when told (e.g., “It's cleanup time.”) Points to at least one color when asked | Says around 50 words Says at least two words with one action word Names items in a book when prompted Uses personal pronouns | |

| Three years | Avoids touching hot objects when warned Conversation of at least two back-and-forth exchanges | Asks who, what, where, and why questions Describes action in a picture Says first name when asked Mostly intelligible to strangers | |

| Four years | Answers simple questions | Uses at least four-word sentences Recites words from song, story, or nursery rhyme States next event in a well-known story Names several colors Talks about at least one thing that happened during their day | |

| Five years | Follows rules when playing games Answers simple questions about a book or story Conversation of more than three back-and-forth exchanges | Tells a multi-event story they heard or created Uses or recognizes simple rhymes Counts to 10 Names some letters and numbers when pointing to them Uses words about time | |

Parents and caregivers significantly influence children's speech and language development by engaging them and promoting social interactions. Family physicians should encourage parents and caregivers to speak to babies and children often, with simplified sentences and clear pronunciation of words. Reading and play are rich opportunities for speech and language promotion that can be integrated into daily routines, helping children build vocabulary and comprehension skills.6–9 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limiting children's screen time in favor of activities focused on social interactions10; screen time has been associated with developmental delays.11,12

Epidemiology

In the United States, up to 1 in 8 children between two and five years of age has a speech or language delay.5 Preschool children with identified speech and language delays that continue into elementary school have a higher risk of additional learning disabilities compared with children with only transient speech and language delays. 13,14 School-aged children with speech and language delays have up to a fivefold higher risk of poor reading skills that can affect the child into adulthood.14,15 Adults with a history of childhood speech or language delay are more likely to work lower-skilled jobs and experience unemployment.14,15 Additionally, these childhood speech and language delays are associated with behavior and psychosocial impairments that can persist into adulthood.14,15

Risk Factors

In 2010, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association published a large study of nearly 5,000 children with a multivariate analysis to identify risk factors consistently associated with established outcome predictors of speech and language impairment, such as parental concerns, use of speech-language pathology services, and low receptive scores.12 The most important risk factors for speech and language impairment were being male, ongoing hearing problems, and birth weight 2,500 g or less (Table 2).12

| Risk factor | Predictors and associated odds ratios (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental expressive concerns | Parental receptive concerns | Use of speech-language pathology services | Low vocabulary score | |

| Birth weight 2,500 g or less | 1.50 (1.18 to 1.91) | 1.75 (1.27 to 2.40) | 1.52 (1.12 to 2.07) | 1.54 (1.14 to 2.09) |

| Male sex | 2.06 (1.80 to 2.35) | 1.84 (1.51 to 2.24) | 1.89 (1.58 to 2.56) | 1.24 (1.05 to 1.47) |

| Sustained hearing issues | 4.27 (3.12 to 5.84) | 6.67 (4.80 to 9.26) | 4.09 (2.88 to 5.80) | 1.60 (1.05 to 2.43) |

Several other factors have not been reliably associated with speech and language delays. Although heterogeneously impacted, children negatively affected by social determinants of health or adverse childhood or family experiences should be considered at-risk of speech and language delay.8,12 Later birth order is not associated with speech and language delays.12 Multilingual environments, as well as regional, social, and cultural variations, can affect initial speech and language development, most often with an ultimate return to a normal development pattern after the early childhood years.16

Children simultaneously learning two or more languages spend less time with each language, and multilingual children tend to perform lower on standardized language tests compared with similarly aged monolingual children. 16 Nonetheless, bilingual status is not associated with increased risk of speech and language delays, and the language used to screen for delays does not affect their identification.12,16

Screening and Surveillance

In the primary care setting, speech and language delay may be identified through milestone surveillance and the use of formal screening tools to assess milestone progression. Screening is the use of validated, standardized tools at specific ages to identify developmental delays.5 Surveillance, the process of recognizing at-risk children, comprises eliciting caregiver concerns, reviewing developmental history, identifying risk factors, and observing the child during the visit.3

The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend surveillance at every well-child visit, with particular attention before elementary school entry at four to five years of age.3 In February 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics, using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance, released updated milestones (Table 13,4) and related parent-oriented materials to facilitate milestone surveillance.4 These evidence-based milestones reflect skills that most children (at least 75%) should achieve at the specified age.4 The CDC's comprehensive list of milestones, Milestone Tracker app, and additional free resources can be accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/ActEarly/Materials. American Family Physician published an editorial about the CDC's revised milestones.17 Children with parental, caretaker, or physician concerns based on surveillance should undergo developmental screenings.3

The American Academy of Family Physicians currently supports the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015 recommendation, which states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against universally screening asymptomatic children five years or younger for speech and language deficits with a validated tool.5,18 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concluded that no screening tool is superior for identification of milestone delays at any age, based on a systematic review.5,15

Multiple screening tools are available for milestone assessments. Screening tools that rely on parental report are common in the primary care setting because of ease of completion and no need for trained examiners.15 The Ages and Stages Questionnaire evaluates communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving, and personal-social domains for children up to five-and-half years of age (https://agesandstages.com/), whereas the Survey of Well-Being of Young Children combines assessments of developmental milestones, childhood behavioral symptoms, and family context from infancy to five years of age (https://pediatrics.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/the-survey-of-wellbeing-of-young-children/overview). Other tools relying on parental report focus predominantly on language and speech concerns (e.g., the Communicative Development Inventories [https://mb-cdi.stanford.edu/] and the Language Development Survey [https://aseba.org/research/the-language-development-survey-lds/]). Screening tools requiring trained examiners, such as the Screening Kit of Language Development, are not practical for use in primary care and do not identify speech and language issues more effectively than less complicated screening methods.15

Initial Evaluation

The differential diagnosis for speech and language delays is broad. These delays can be classified as secondary to other conditions or as primary conditions without apparent underlying causes.2,19 Table 3 outlines common primary and secondary causes of speech and language delays.2,20–25 Many neurodevelopmental disorders cause secondary speech and language delays. Associated disorders can predominantly affect development of speech, language, or both.

| Disorder | Clinical findings and comments | Treatment and prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary disorder* | ||

| Childhood-onset fluency disorder (stuttering and cluttering) | Stuttering includes speech and fluency disturbances, such as sound repetitions and prolongations, broken words, speech pauses, circumlocutions, or excess physical tension with words2,20 First-degree relatives of people who stutter have a three times higher risk of stuttering than the general population 2; multiple genes have been isolated and associated with stuttering20 Cluttering is abnormally fast or irregular speech delivery rate, leading to unexpected sounds, phrases, patterns, or dysfluencies in speech21 | Focuses on speaking more slowly, breathing regulation, feedback training, and muscle tension reduction20–23 |

| Language disorder | Reduced vocabulary, limited sentence structure, and impaired ability to carry conversation in spoken, written, or sign language or other comprehension or production deficits Not caused by hearing or other sensory loss, motor dysfunction, or another medical or neurologic condition Highly heritable2 | Focuses on knowledge and use of language for all modalities of communication20–23 Likely to continue into adulthood; delays presenting after four years of age are predictive of long-term outcomes, whereas delays before four years of age are not2 |

| Social (pragmatic) communication disorder | Social verbal and gestural difficulties, including appropriate use of eye contact, facial expressions, body language, and emotional expression2,20 | Includes mediating social exchanges through instruction, modeling, role-play, and cognitive behavior therapies20–23 |

| Secondary causes | ||

| Autism spectrum disorder | Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, nonverbal communicative behaviors, and understanding relationships; restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities2 | Focuses on specific speech-language deficits, including motor function, semantics, social communication, and receptive and expressive language skills; augmentative and alternative communication† methods may also be used20,22–24 Not a degenerative disorder; positive prognostic factors include absence of intellectual disability, language impairment, and additional mental health problems2 |

| Cerebral palsy | Movement disorder from perinatal brain damage, which causes subsequent intellectual and sensory deficits; speech and gestural difficulties are common2,20 | Focuses on language skills, articulation, and proper breathing for speech and swallowing; augmentative and alternative communication† methods may also be used20,22–24 |

| Craniofacial disorders | Cleft lip/palate, dental malocclusion, macroglossia, or 22q11.2 deletion syndrome2,22 | Requires multidisciplinary approach, including craniofacial, dental, audiologic, and speech-language services20,22,23 |

| Global developmental delay | Failure to meet developmental milestones in several areas of intellectual function in children younger than five years2 | Precursor to intellectual disability20 |

| Hearing loss after spoken language established | Often affects speech articulation and volume and leads to gap in vocabulary attainment25 Conductive hearing loss is often due to outer and middle ear pathology (e.g., auditory canal obstruction, otitis media or externa, tympanic membrane rupture, tympanostomy tubes) Sensorineural hearing loss is due to damage to inner ear or neural pathways (e.g., from congenital infections, meningitis, ototoxic medications, tumors, or trauma)25 | Involves addressing underlying cause, audiologic rehabilitation, and compensating for hearing loss with alternative communication modalities (e.g., sign language), hearing aids (for conductive or sensorineural hearing loss), or cochlear implants with intensive audiologic rehabilitation for profound hearing loss Early detection and intervention are critical to minimizing sequelae of hearing loss Hearing loss at birth or within first few months of life has the most profound effect on language development25 |

| Hearing loss before onset of speech | Speech expression and comprehension are delayed25 | |

| Intellectual developmental disorder | Deficits in intellectual functions and adaptive functioning in comparison with peers that is first noted during developmental period Child often has associated difficulties with social judgment; self-management of behavior, emotions, or relationships; and communication skills Known causes include genetic syndromes (e.g., Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, Williams syndrome, Rett syndrome)2 | Lifelong, but generally nonprogressive except in certain genetic disorders (e.g., Rett syndrome) or epilepsy disorders (e.g., Lennox-Gastaut syndrome)2 |

| Myofunctional disorder (tongue thrust) | Tongue thrusting at rest or during swallowing, lip incompetency, and sucking habits21 | Structural assessment and diagnostic procedures guide management20,22,23 |

| Vocal cord dysfunction | Inappropriate vocal cord movement that affects respiratory function and voice production; often presents with chronic cough, episodes of breathing difficulty, throat or chest tightness, and sensation of choking; often misdiagnosed as asthma, allergies, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or upper airway obstruction20,22 | Focuses on behavior interventions to improve symptoms and reduce recurrences, such as relaxed-throat breathing, breathing exercises, and chronic cough suppression strategies20,22,23 |

Family physicians can elicit clues from the child's history provided by parents or caretakers to augment milestone surveillance and to identify speech and language delays and associated causes (Table 4).1,2,22 Any abnormal surveillance warrants additional evaluation with a validated screening tool. Pertinent physical examination elements include the HEENT (head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat) examination, with particular attention to the ears and mouth for structural abnormalities, such as cleft palate, and a neurologic examination to assess for motor dysfunction.22

| Comprehension issues (e.g., not combining two words at two years of age) |

| Environment where difficulties are most apparent (i.e., home, school, daycare) |

| Expression issues (e.g., mispronouncing words or specific sounds) |

| Family history of developmental delays |

| Other developmental delays or concerns (i.e., motor, social) |

| Other languages spoken or understood |

| Preferred language at home |

Referral Recommendations

Specialist consultation is appropriate for children with screening abnormalities, parent concerns, or physician concerns,3,19,22 beginning with speech-language pathology and audiology evaluations. Watchful waiting is not recommended for late talkers, such as children with a vocabulary of fewer than 50 words at 24 months or older or without word combinations or children not meeting screening test thresholds.3,26 Delays in care may result in long-lasting adverse effects on communication development.26 One study focusing on children with speech and language delays persisting into school age noted an association between long-standing speech and language abnormalities and social and attention deficits.14 The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association recommends early identification and treatment of speech and language delays to minimize these adverse effects on social development and school performance.22

Immediate referral should be considered for expressive or receptive language concerns or deficits noted after two years of age, speech and language milestone regression, and speech that remains incomprehensible after two years of age.19,22,26 Referral criteria are the same for monolingual and bilingual children. Speech and language interventions are most effective when introduced in all spoken languages, which may require the assistance of interpreters.21

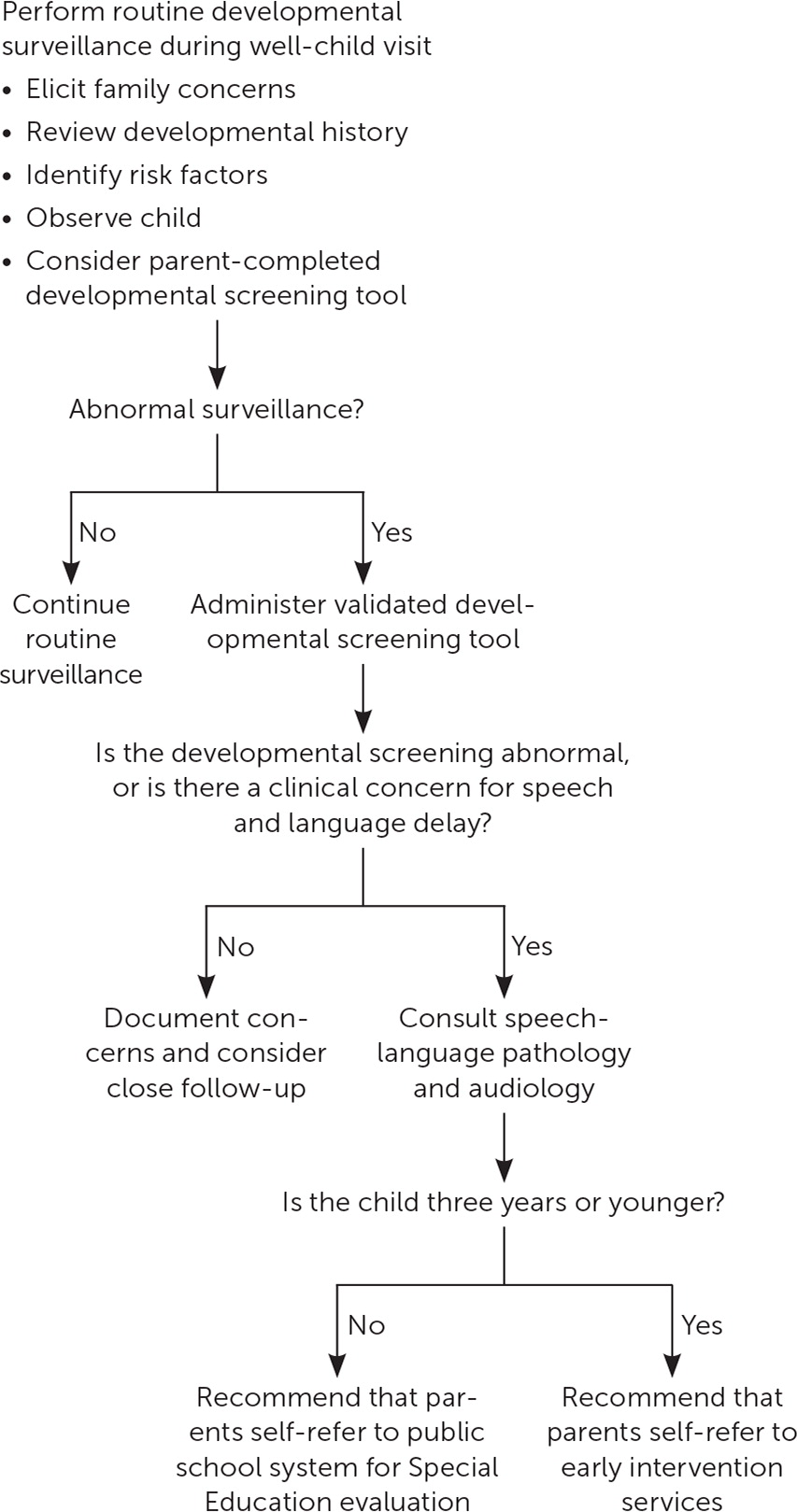

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends universal hearing screening after birth; at four, five, six, eight, and 10 years; and between 11 and 14 years, 15 and 17 years, and 18 and 21 years.27 If testing has not recently been performed in a child with a suspected speech or language delay, an audiologist should evaluate for underlying hearing loss.27 When speech and language delays are suspected to be secondary to neurodevelopmental disorders, physicians can also consult behavioral health specialists, including pediatric psychologists and psychiatrists, for further evaluation and management. Specialists in pediatric neurology and developmental pediatrics are helpful for diagnosis and treatment, although local availability may be limited. Figure 1 outlines an approach to the initial evaluation and management of a child with speech and language concerns.

Early Intervention

Early intervention programs are government-funded multi-disciplinary programs designated to support families with young children and infants with developmental delays. These self-referral programs offer speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy services to children younger than three years. Services are free of charge or priced according to income. Parents and guardians of children younger than three years can directly contact state-run early intervention programs through information found on the CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/parents/state-text.html). Parents and guardians of children three years or older can contact any local public elementary school to request school system evaluation for special education services, regardless of whether the child is enrolled at that facility. Parents may find additional information on the associated CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/concerned.html/#childthree).

This article updates previous articles on this topic by McLaughlin1 and Leung and Kao.28

Data Sources: PubMed and Cochrane databases were searched using terms speech, language, and developmental delay. The search included randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and clinical reviews. Additionally, an Essential Evidence Plus summary report on this topic was used to assist in the literature review. Search dates: February 2023 and June 21, 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.