Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(3):315-320

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Key Points for Practice

• Given the evidence of delayed progression and decreased mortality, certain interventions should be started in patients at risk of heart failure who do not have symptoms.

• Guideline-directed medical therapy can reduce all-cause mortality by 73% compared with no treatment.

• If ejection fraction improves with guideline-directed medical therapy, stopping medications is associated with a high recurrence risk.

• In symptomatic heart failure, care from multidisciplinary teams is associated with improvements in mortality and function.

From the AFP Editors

Heart failure represents a broad spectrum of disease caused by impaired ventricular filling and contraction. While incidence has decreased over the past decade, mortality from heart failure has been increasing. The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines, with members of the Heart Failure Society of America, published new guidelines on managing the condition, which include recommendations for patients at risk of heart failure and focus on therapy to prevent progression.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of heart failure is based on the presence of structural heart disease with current or previous symptoms. Clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of heart failure are nonspecific and include jugular venous distention, orthopnea, shortness of breath when bending down, and leg edema.

In patients with suspected or new-onset heart failure as indicated by symptoms, examination, or electrocardiography changes, chest radiography should be performed to evaluate heart size and pulmonary congestion and to rule out other possible causes. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels should also be measured. If heart failure is suspected, echocardiography is recommended because treatment varies with ejection fraction.

Measurement of BNP levels is most useful for ruling out suspected heart failure because of its high negative predictive value. Although the N-terminal prohormone assay is more accurate, both assays are useful. In a patient with known heart failure, BNP levels change with disease stage, but they are not precise enough to guide therapy. During admission for heart failure, decreasing BNP levels are associated with improved outcomes.

Grading

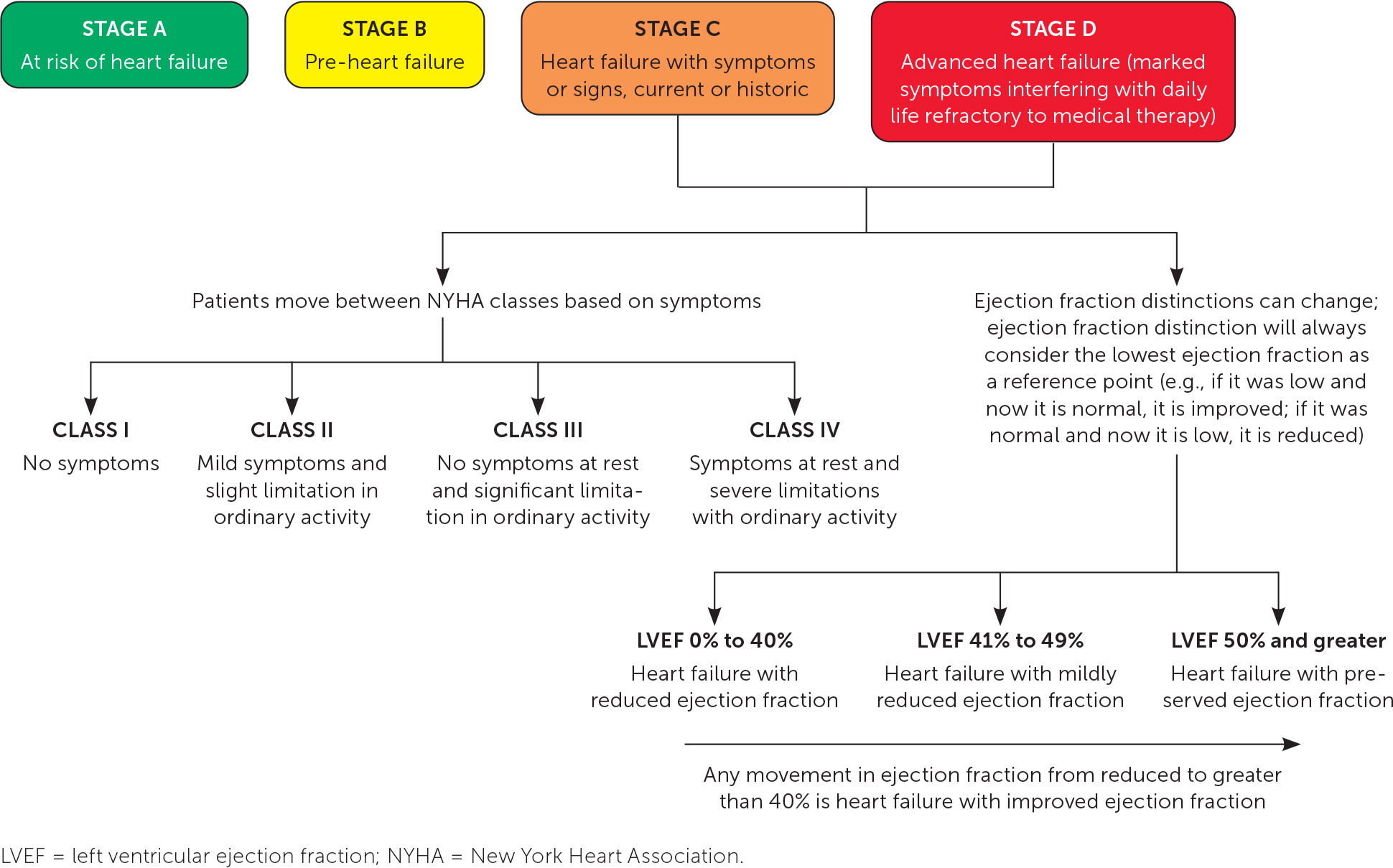

Heart failure can be characterized by stage, ejection fraction, and functional status (Figure 1). Stages can guide initial treatment of asymptomatic patients. Treatment decisions for documented heart failure can be based on ejection fraction and further adjusted by symptom response.

STAGE

The AHA/ACC guidelines divide heart failure into four stages; the first two describe patients at risk of heart failure and the second two describe patients with heart failure. The condition is characterized by symptoms and structures that highlight the course of the disease.

Stage A is defined by the presence of a risk factor of heart failure without structural changes or symptoms. These patients are at risk due to hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or coronary artery disease, and controlling these risk factors can prevent progression to heart failure.

Patients in stage B (i.e., pre-heart failure) have structural changes in the heart but are currently without signs or symptoms. Affected patients include those with reduced ejection fraction, congenital heart disease, or valvular heart disease with impaired hemodynamics.

Patients in stage C are those with structural changes and previous or current symptoms.

Stage D represents symptomatic heart failure refractory to goal-directed medical therapy.

EJECTION FRACTION

Characterization by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is primarily relevant in stages C and D. Therapy can be tailored by LVEF ranges.

LVEF of 50% or more is classified as preserved.

LVEF of 41% to 49% is classified as mildly reduced. Most patients in this range have a different ejection fraction at the next evaluation.

LVEF of 40% or less is classified as reduced.

LVEF that has improved from 40% or less to greater than 40% is classified as improved.

FUNCTIONAL STATUS

The New York Heart Association classification system (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3987/new-york-heart-association-nyha-functional-classification-heart-failure) is applicable to stages C and D because it characterizes function according to symptoms. Despite being subjective, changing over time, and having limited reliability, this classification is an independent predictor of mortality.

Treatment Overview by Stage

STAGE A

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors should be prescribed for patients who have diabetes with or at elevated risk of cardiovascular disease to reduce hospitalization by reducing risk of symptomatic heart failure.

STAGE B

Stage B management focuses on guideline-directed medical therapies for the conditions causing structural changes in the heart.

Several medications improve all-cause mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, regardless of the presence of symptoms.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are the cornerstone of treatment for patients in stage B to reduce progression to symptomatic heart failure and reduce mortality. An angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) can be used in patients with a recent myocardial infarction who cannot tolerate an ACE inhibitor.

Patients with a history of myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome and a reduced ejection fraction should be started on a cardioprotective beta blocker (e.g., bisoprolol, carvedilol [Coreg], sustained-release metoprolol succinate) to reduce mortality.

The guidelines specifically recommend against the use of thiazolidinediones and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in any patient with LVEF of 50% or less.

STAGES C AND D

Guideline-directed medical therapy is a key treatment element of stage C heart failure.

In stage D, patients typically require specialized teams to direct management. Treatment focuses on advanced therapies such as transplants and left ventricular assist devices, or palliation and hospice in alignment with the patient's condition, values, and preferences.

Treatment Recommendations by Ejection Fraction

Patients with symptoms should receive all four components of guideline-directed medical therapy (Table 1). Treatment with all four components is estimated to reduce all-cause mortality by 73% compared with no treatment.

| Stage | Left ventricular ejection fraction | New York Heart Association functional classification | Management recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (at risk of heart failure) | NA | NA | Consider SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes Control comorbidities |

| B (pre-heart failure) | ≤ 40% | Class I | ACE inhibitors or ARBs Control comorbidities Heart failure–specific beta blockers |

| > 40% | NA | Control comorbidities | |

| C and D (symptoms present) | ≤ 40% (HFrEF) | Class I | ACE inhibitors or ARBs Control comorbidities Heart failure–specific beta blockers |

| Class II | ARB/neprilysin inhibitor preferred, or ACE inhibitor or ARB Control comorbidities Heart failure–specific beta blockers Loop diuretic, if congested Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists SGLT-2 inhibitors | ||

| Class III | ARB/neprilysin inhibitor preferred, or ACE inhibitor or ARB Control comorbidities Heart failure–specific beta blockers Loop diuretic, if congested Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists SGLT-2 inhibitors | ||

| Class IV | Control comorbidities Heart failure–specific beta blockers Loop diuretic, if congested Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists SGLT-2 inhibitors | ||

| 41% to 49% (HFmrEF) | Class I | See stage B | |

| Class II Class III Class IV | Consider based on ejection fraction and status: ARB/neprilysin inhibitor preferred, or ACE inhibitor or ARB Heart failure–specific beta blockers Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists Control comorbidities Loop diuretic, if congested SGLT-2 inhibitors | ||

| ≥ 50% (HFpEF) | Class I | See stage B | |

| Class II Class III Class IV | Consider based on ejection fraction and status: ARB/neprilysin inhibitor preferred, or ACE inhibitor or ARB Heart failure–specific beta blockers Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists Control comorbidities Loop diuretic, if congested SGLT-2 inhibitors | ||

| Improved from ≤ 40% (HFimpEF) | All classes | Continue guideline-directed medical therapy based on lowest previous ejection fraction |

REDUCED EJECTION FRACTION (LVEF OF 40% OR LESS)

Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. ARB/neprilysin inhibitors, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs are all effective in reducing mortality in heart failure. All reduce mortality at similar rates.

An ARB/neprilysin inhibitor is recommended in patients with reduced LVEF and New York Heart Association class II or III symptoms to reduce morbidity and mortality. An ACE inhibitor can be substituted if ARB/neprilysin inhibitor treatment is not possible. ARBs are a third-line option if the other two treatments are not feasible.

ARB/neprilysin inhibitors outperform ACE inhibitors in direct comparison, and the ARB/neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto) reduces a composite end point of cardiovascular death and hospitalization by 20% compared with the ACE inhibitor enalapril. ARB/neprilysin inhibitor initiation at discharge or during hospitalization is safe in symptomatic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Because neprilysin inhibitors can cause angioedema, a 36-hour delay from the last ACE inhibitor dose is suggested before initiating treatment. Symptomatic hypotension is more common in patients treated with ARB/neprilysin inhibitors vs. those treated with ACE inhibitors. If tolerance of ARB/neprilysin inhibitor therapy is poor, an ACE inhibitor is preferred over an ARB.

Beta blockers. Treatment with a cardioprotective beta blocker has been shown to reduce the risk of death and combined risk of death or hospitalization in patients with heart failure. A cardioprotective beta blocker can be started during initial hospitalization.

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. This treatment reduces all-cause mortality, and benefits are consistent across reduced ejection fraction levels. Examples include spironolactone and eplerenone. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists should be avoided in patients with renal insufficiency and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 30 mL per minute or less. Treatment should be discontinued if serum potassium levels cannot be maintained at less than 5.5 mEq per L (5.5 mmol per L).

SGLT-2 inhibitors. This treatment is recommended in heart failure, regardless of diabetes status, because it reduces all-cause mortality with a number needed to treat of 63 over one year. SGLT-2 inhibitors reduce heart failure hospitalizations by 31% in people with diabetes and without heart failure, and by 30% in people with both diabetes and heart failure. These agents increase the risk of genital infections and euglycemic ketoacidosis and the need for diuretic adjustment to avoid fluid depletion. Despite their high cost, this treatment offers intermediate economic value based on a cost of $60,000 to $90,000 per quality-adjusted life-year.

Other medications. The guidelines also recommend prescribing isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine to patients with New York Heart Association class III or IV symptoms who self-identify as African American to improve symptoms and reduce morbidity and mortality. The combination can also be used in patients who cannot be given first-line treatment, such as renin-angiotensin system inhibitors.

Based on moderate evidence, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids can be recommended to patients to decrease mortality and hospitalizations.

MILDLY REDUCED EJECTION FRACTION (LVEF OF 41% TO 49%)

Patients with mildly reduced ejection fraction benefit from diuretic therapy when there is evidence of fluid overload. Post-hoc analyses of trials suggest that all elements of guideline-directed medical therapy benefit patients with mildly reduced ejection fraction. In one trial, SGLT-2 inhibitors reduced time to hospitalization for heart failure by 29%. Cardioprotective beta blockers reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with mildly reduced ejection fraction and sinus rhythm. Similarly, ARB/neprilysin inhibitors, ARBs, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists appear to improve outcomes.

PRESERVED EJECTION FRACTION (LVEF 50% OR MORE)

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction represents approximately one-half of clinically diagnosed heart failure cases, yet the elements of guideline-directed medical therapy tend not to improve outcomes. Patients benefit from diuresis when there is evidence of fluid overload. SGLT-2 inhibitors also appear to improve outcomes. In one trial, the miner-alocorticoid receptor agonist spironolactone mildly reduced hospitalizations.

IMPROVED EJECTION FRACTION (LVEF IMPROVED FROM 40% OR LESS TO MORE THAN 40%)

Because heart failure treatment is based on ejection fraction, the management of patients whose ejection fraction improves with therapy is uncertain. One study indicates that the improved ejection fraction should not be used to guide therapy. In this study, stopping guideline-directed medical therapy led to heart failure relapse in 40% of patients within six months.

Nonpharmacologic Management

The most important element of heart failure management may be multidisciplinary teams, which reduce all-cause mortality, all-cause hospitalization, and heart failure hospitalization according to a Cochrane review. In addition, the guidelines recommend screening for several social determinants of health, including social isolation, frailty, and low health literacy, to guide management.

Exercise training or regular physical activity is recommended to improve function and quality of life. Patients should also consider limiting sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg per day, although this recommendation is not based on research showing patient-oriented evidence of benefit in heart failure. Lifestyle recommendations are challenged by limited evidence.

Symptom Management

A diuretic can be used by patients who have fluid retention to improve symptoms and reduce symptom progression. To reduce the risk of electrolyte abnormalities, a combination of a thiazide and a loop diuretic should be limited to patients who have symptoms that do not improve with moderate- or high-dose loop diuretic monotherapy.

Implantable Devices

Implantable devices, including cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy, can improve outcomes for patients. Cardioverter-defibrillators reduce all-cause mortality with a number needed to treat of 70 over one year in symptomatic patients with LVEF of 35% or less or asymptomatic patients with LVEF of 30% or less. The strongest evidence involves patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy or ischemic disease who are at least 40 days past a myocardial infarction, receive optimized guideline-directed medical therapy, and have a life expectancy of more than one year.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with reduced LVEF of 35% or less, sinus rhythm, left bundle branch block, and widened QRS complex with heart failure symptoms who receive optimized guideline-directed medical therapy. It also reduces combined end points of death and hospitalization for heart failure.

Inpatient Management

Admissions for heart failure are usually due to increased filling pressure and subsequent fluid overload. Continuing guideline-directed medical therapy reduces the risk of post-discharge death and readmission compared with discontinuation of treatment at admission. For patients not receiving or adhering to guideline-directed medical therapy, initiation and titration are safe during admission.

Inpatient management frequently depends on diuresis, which improves symptoms and reduces morbidity. Elevations in serum creatinine up to 0.3 mg per dL (26.5 μmol per L) do not predict worse outcomes in patients undergoing diuresis. Basal and bolus dosing of intravenous diuretics appear to be equally safe. To begin treatment, physicians often double the outpatient oral dosage and convert it to an intravenous dosage. Patients admitted for heart failure exacerbations should receive prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism, care coordination, and patient-centered approaches to discharge.

| Score | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Yes | Focus on patient-oriented outcomes |

| Yes | Clear and actionable recommendations |

| Yes | Relevant patient populations and conditions |

| Yes | Based on systematic review |

| Yes | Evidence graded by quality |

| Yes | Separate evidence review or analyst in guideline team |

| Yes | Chair and majority free of conflicts of interest |

| Yes | Development group includes most relevant specialties, patients, and payers |

| Overall – useful |

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Editor's Note: Because family physicians frequently manage heart failure, in the clinic and the wards, this information is important for our readers. Yet, like many publications from this joint committee, this guideline makes recommendations based on various-quality evidence with limited adherence to their own rating scales. An example is the inclusion of a Level A race-based recommendation for isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine for people who self-identify as African American, are receiving guideline-directed medical therapy, and still have New York Heart Association class III or IV symptoms. The description includes a detailed criticism of the single trial stopped early, the uncertainty of the racial designation, the effect of this treatment in other populations, and even the poor adherence due to dosing and adverse effects, but none of this affects the evidence rating. Although many recommendations are useful, the lack of assessment limits the practical utility of the guidelines for those not initially deterred by the 138-page length.—Michael J. Arnold, MD, Assistant Medical Editor

Guideline source: American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology

Published source: Heindenreich PA, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure [published corrections appear in Circulation. 2022;145(18):e1033, Circulation. 2022;146(13):e185, and Circulation. 2023;147(14):e674]. Circulation. May 3, 2022;145(18):e895–e1032.