Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(3):240-248

Patient information: See related handout on smell and taste disorders.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Disorders of smell and taste are reported by approximately one-fifth of people 40 years and older, and one-third of people 80 years and older. These disorders affect quality of life and the ability to identify smoke and toxins. Smell and taste disorders can be early signs of dementia or Parkinson disease and are associated with increased mortality. Dysfunction may be apparent or may develop insidiously. Screening questionnaires are available, but many patients are unaware of their disorder. Most smell and taste disorders are due to sinonasal disease but also could be caused by smoking, medications, head trauma, neurodegenerative disease, alcohol dependence, or less common conditions. The differential diagnosis should guide the evaluation and include anterior rhinoscopy and an examination of the oral cavity, head, and cranial nerves. Further investigation is often unnecessary, but nasal endoscopy and computed tomography of the sinuses may be helpful. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head with contrast should be performed if there is an abnormal neurologic examination finding or if trauma or a tumor is suspected. Olfactory testing is indicated in refractory cases or for patients with poor quality of life and disease associated with smell or taste dysfunction. Smell and taste disorders may resolve when reversible causes are treated, but improvement is less likely when they are due to trauma, age, or neurodegenerative disease. Olfactory training is a self-administered mindful exposure therapy that may improve olfactory function. Physicians should encourage patients to ensure that smoke and other alarms are operational and to adhere to food expiration dates.

Disorders of smell and taste affect a person's quality of life, health, and safety. The COVID-19 pandemic renewed attention to these disorders, and one of the Healthy People 2030 objectives is to increase the proportion of adults with smell or taste disorders who discuss the problem with a clinician.1 Olfactory dysfunction is reported by 23% of people in the United States 40 years and older and 39% of those 80 years and older.2,3 Altered taste is reported by 19% of people 40 years and older, and 27% of those 80 years and older.2 Smell and taste disorders can affect food consumption habits, which may lead to chronic disease3 (Table 14). Depression, poor sleep, dementia, unintentional weight loss, and malnutrition are associated with disordered smell or taste.5–15 The ability to detect sources of danger, such as smoke or poison, depends on smell or taste.10,11 When directly tested, 20.3% of a nationally representative sample of adults 70 years and older without known dysfunction misidentified smoke, and 31.3% misidentified natural gas.3

| Dysfunction in smell and taste occurs in 40% to 50% of patients diagnosed with COVID-19, often without rhinorrhea or nasal congestion. |

| A prospective cohort study found that recovery of smell and taste after COVID-19 occurred for most patients by seven days, and more than 80% recovered by three months. |

| When directly tested, 20.3% of a nationally representative sample of adults 70 years and older without known olfactory dysfunction misidentified the scent of smoke, and 31.3% misidentified the smell of natural gas. |

| More than 95% of patients with Parkinson disease have smell impairment, and up to 75% have anosmia or hyposmia. |

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Patients should be referred to otolaryngology for objective testing of olfactory or gustatory function in refractory cases or if they have depression, poor sleep, dementia, unintentional weight loss, or malnutrition.3,20,38–40 | B | Case series of 602 patients, multiple observational studies |

| Olfactory training should be offered to patients with persistently poor quality of life due to olfactory dysfunction.63–65 | A | Consistent evidence from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses, including randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies, showing clinically significant improvement after viruses and other etiologies |

| Physicians should counsel patients with olfactory dysfunction about the risks of occupational chemical exposure, adherence to food expiration dates, signs of food spoilage, and home fire and explosive gas monitoring.3,40 | C | Expert opinion and a cross-sectional study |

| Disorder | Description |

|---|---|

| Taste | |

| Ageusia | Complete loss of ability to taste |

| Dysgeusia | Distorted taste perception (triggered by a taste stimulus) |

| Hypogeusia | Reduced ability to taste |

| Phantogeusia | Gustatory hallucination (occurs without a stimulus) |

| Smell | |

| Anosmia | Complete loss of ability to smell |

| Hyposmia | Reduced ability to smell |

| Parosmia | Distorted odor perception (triggered by a stimulus) |

| Phantosmia | Olfactory hallucination (occurs without a stimulus) |

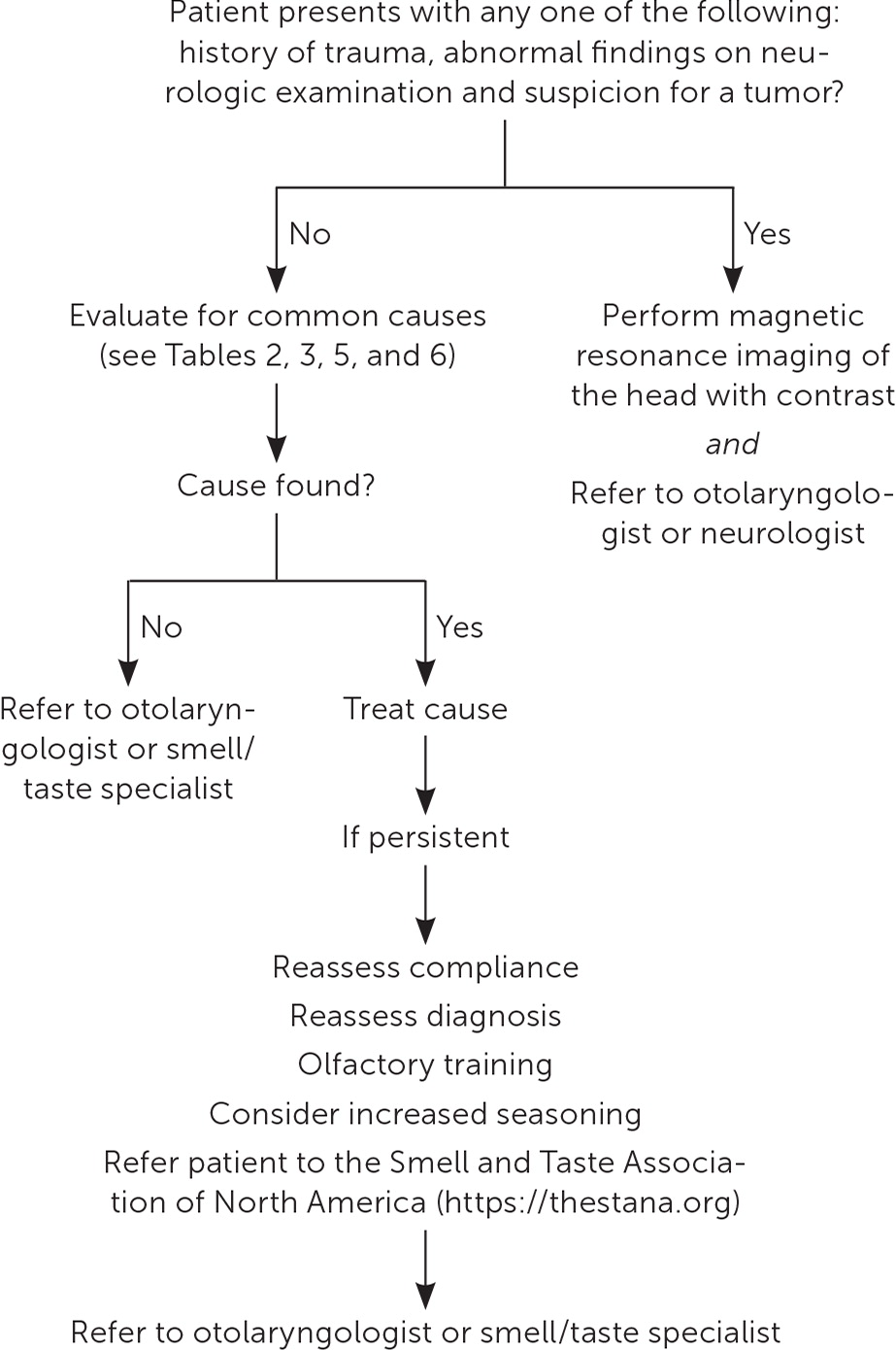

There are many clinical presentations and causes for smell and taste disorders (Table 2).16–19 Etiologies range from sinonasal disease to less common conditions such as Sjögren syndrome (Table 3).4 When only taste disorder is perceived by the patient, it is often due to olfactory dysfunction.20–26 Therefore, without an apparent taste insult, physicians should focus their evaluation on the olfactory system. Figure 1 provides an approach to evaluating smell and taste disorders in primary care.

| Cause | Pathology | History |

|---|---|---|

| Age-related (presbyosmia) | Loss or replacement of olfactory neurons with respiratory epithelium Decreased basal cell proliferation Decrease of interneurons in olfactory bulb with reduced activity in olfactory cortex | Insidious onset; unlikely to see improvement Olfactory dysfunction predicts five-year mortality |

| Neurodegenerative causes (e.g., Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease) | Alzheimer disease: neurofibril changes in the olfactory bulb and higher olfactory network Parkinson disease: Lewy bodies deposited in the olfactory tract, olfactory bulb, and anterior olfactory nucleus17 | Insidious onset; unlikely to see improvement Onset can be early in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases |

| Other medication/toxin exposure/iatrogenic | Altered receptor function by binding G-protein coupling or affecting calcium or sodium channel activity | Sudden onset; mostly resolves with ceasing exposure; can persist in some cases requiring treatment; can have medicolegal implications18 |

| Postviral olfactory dysfunction | Viral common cold pathogens, COVID-19, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, parvovirus, HIV Long-term inflammation causes neuroepithelial remodeling to respiratory epithelium | Sudden onset with little fluctuation; often associated with parosmia; one in three recovers in the 14 months after presentation for care19 |

| Posttraumatic olfactory dysfunction | Severing of olfactory nerve filament or central nervous system injury | Sudden or delayed onset; fluctuation is uncommon; phantosmia and parosmia are common 10% recover by 13 months, but up to 35% can recover depending on severity19 |

| Sinonasal (e.g., chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps) | Obstruction of the olfactory cleft; temporary interference with olfactory receptor binding due to inflammation; eventual neuroepithelial remodeling/central nervous system changes | Gradual onset and fluctuation over time; typically improves with nasal/systemic corticosteroids Not commonly associated with parosmia |

| Cause | Leading etiologies* |

|---|---|

| Most common | |

| Sinonasal conditions | Upper respiratory tract infection (especially viral, including COVID-19), allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps |

| More common | |

| Head trauma | Damage to cribriform plate, shearing forces, and intracranial damage; facial trauma |

| Neurodegenerative disorders | Parkinson disease, parkinsonism, Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, multiple sclerosis |

| Less common | |

| Medications | Chemotherapy, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, diuretics, intranasal zinc, antimicrobials (macrolides, terbinafine, fluoroquinolones, protease inhibitors, griseofulvin, penicillins, tetracyclines, nitroimidazoles [metronidazole (Flagyl)]), antiarrhythmics, antithyroid agents, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, lipid-lowering agents |

| Intoxicants or illicit substances | Alcohol dependence, cocaine use |

| Toxins | Ammonia, hairdressing chemicals, gasoline, formaldehyde, paint solvents, welding agents, benzene, sulfuric acids, cadmium, acrylates, iron, lead, chromium |

| Chronic medical conditions | Renal or hepatic failure, complicated type 2 diabetes mellitus, cancer, HIV |

| Structural or mechanical conditions | Ischemic stroke, subarachnoid or intracranial hemorrhage, brain or sinonasal tumor |

| Nutritional deficiencies | Malnutrition, pernicious anemia or vitamin B12 deficiency, deficiencies in vitamins B6 or A, niacin, zinc, or copper |

| Postsurgical state | Nasal surgery (septal or sinus) |

| Postradiation | Especially to head and neck |

| Congenital conditions | Kallmann syndrome, anosmia |

| Psychiatric conditions | Anorexia nervosa (not bulimia), major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia |

| Endocrine conditions | Pregnancy, hypothyroidism, Addison disease, Cushing syndrome |

| Autoimmune/inflammatory conditions | Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, herpes encephalitis |

Anatomy and Physiology

Chemicals that cause smells (i.e., odorants) are absorbed through the mucosa of the nose, nasopharynx, and oropharynx. Odorants stimulate olfactory neurons in the neuroepithelium over the cribriform plate. Olfactory neurons project directly to the olfactory bulb, which communicates with the olfactory cerebral cortex. Olfactory receptors regenerate every eight to 10 days, followed by five days for the maturation of cilia.27–29 Dysfunction along these pathways can result in a smell disorder.30–32

Odorants and tastants (i.e., particles and liquids that cause the taste sensation) dissolve in saliva and directly contact gustatory receptors in dedicated cells for each of the five tastes (bitterness, saltiness, sourness, sweetness, and umami [savory]). These cells are in taste buds on the tongue, soft palate, pharynx, larynx, epiglottis, and the proximal one-third of the esophagus. Different nerves innervate the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, posterior one-third of the tongue, palate, pharynx, and larynx. The trigeminal nerve also mediates certain characteristics of smell and taste, such as irritation and temperature. Taste is mediated by several different nerves depending on anatomic location; therefore, gustatory loss is less common than olfactory loss.9,33,34

Clinical Assessment

HISTORY

Validated questionnaires help clinicians screen for subjective olfactory dysfunction (Table 4).11,35,36 A National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey used three questions that were not formally validated but are a reasonable approach to screen patients for olfactory dysfunction.2,3 There are no validated subjective tools to assess taste.16

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey questionnaire:

| |

| Self-reported Mini Olfactory Questionnaire (five items) | https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/lary.28419#lary28419 |

| Brief Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders–negative statements (seven items) | https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/alr.22800 |

| Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders–negative statements (17 items) | https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.usu01.idm.oclc.org/doi/epdf/10.1002/lary.23349 |

Smell influences taste; therefore, it can be challenging to distinguish which sense is disordered and determine the severity of the disorder. The history should include inquiries about medications, supplement use, nose or mouth pain, and symptoms or history of dry mouth, rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, recent upper respiratory tract infection, or trauma. In older patients, the history should include queries about symptoms of Parkinson disease or dementia.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should include anterior rhinoscopy (visual examination of the anterior nasal passages) and examination of the head, oral cavity, and neurologic system. Findings suggestive of a sinonasal etiology include intranasal masses, edematous mucosa, hypertrophic turbinates, purulent mucus, or bleeding. Anterior rhinoscopy is necessary for isolated taste dysfunction because olfactory dysfunction and sinonasal etiologies are commonly found. Nasal endoscopy is much more sensitive (91%) for identifying sinonasal pathology and may be necessary if the initial examination is inconclusive.37 Examination of the oral cavity may find inflammation, plaque, erosions of the tongue or mucosa, or masses. Evidence of head trauma or neurologic dysfunction warrants an additional neurologic examination and specialized testing.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Smell and taste disorders are often due to common conditions readily treated by family physicians without specialized testing. However, because patients often underestimate or do not recognize their dysfunction, many experts recommend having a low threshold for obtaining otolaryngology consultation for objective testing of olfactory function.3,20,38–40 Family physicians should consider olfactory testing for refractory cases and for patients with a poor quality of life who are affected by conditions associated with olfactory or gustatory dysfunction (e.g., depression, poor sleep, dementia, unintentional weight loss, malnutrition; Table 54). Taste function testing is performed in dedicated centers.16,41

| Category* | Leading etiologies |

|---|---|

| Poor oral hygiene, infection/inflammation | Gingivitis, oral abscess, oral candidiasis, periodontal disease, viral upper respiratory tract infection |

| Oral appliances | Dentures, prosthetics (hypothesized to be related to oral inflammation if poor hygiene with appliances) |

| Postsurgical state | Middle ear surgery affecting chorda tympani (usually transient), oral or dental surgery (especially third molar extraction) |

| Radiation | Head and neck irradiation with oral mucositis, xerostomia |

| Nutritional | Copper supplementation; deficiency of copper, vitamin B3 (niacin), vitamin B12, or zinc (rare); general malnutrition |

| Medications | Intranasal zinc, chlorhexidine, chemotherapy, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, diuretics, antimicrobials (macrolides, terbinafine, fluoroquinolones, protease inhibitors, griseofulvin, penicillins, tetracyclines, nitroimidazoles [metronidazole (Flagyl)]), antiarrhythmics, antithyroid agents, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, lipid-lowering agents |

| Head trauma | Head or facial trauma |

| Toxins | Pepper gas (oleoresin capsicum), weed killer with trifluralin, ammonia, benzene, sulfuric acids, cadmium, acrylates, iron, lead, chromium |

| Chronic medical conditions | Renal or hepatic failure, cancer, HIV, complicated type 2 diabetes mellitus |

Imaging is not necessary when the initial history and physical examination identify common benign and treatable atraumatic etiologies. If further investigation of the sinuses is warranted, computed tomography without contrast is preferred. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head with contrast is warranted when there is a history of trauma, an abnormal neurologic examination finding, or suspicion for a tumor.

Causes of Smell and Taste Disorders

SINONASAL CONDITIONS

Most olfactory dysfunction is caused by sinonasal conditions, such as nasal polyps, allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, and upper respiratory tract infection. Olfactory dysfunction associated with sinonasal disease usually resolves with successful treatment of the related condition. Oral and nasal corticosteroids are often used to treat some of these conditions. Corticosteroids may improve the transmission of odorants to the olfactory nerve epithelium by decreasing local swelling and inflammation.42 Multiple systematic reviews evaluated possible pharmacotherapies for postviral olfactory dysfunction and found relatively low-quality evidence. Nasal corticosteroids showed a small benefit and a minimal risk. Studies on zinc did not show consistent benefits.43 One industry-sponsored, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of 323 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps with anosmia or hyposmia found that fluticasone propionate, delivered via an exhalation delivery system, yielded a clinically significant improvement in patient-reported sense of smell.44 Oral corticosteroids may improve symptoms but, due to potentially severe adverse effects, their use should be limited (three to seven days) and reserved for severe symptoms refractory to other medical therapies.45 A prospective cohort study found improved olfactory function and olfactory bulb volume six months after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps.46

COVID-19

Smell and taste dysfunction occurs in 40% to 50% of patients diagnosed with COVID-19.47 The dysfunction tends to improve or resolve more quickly than other etiologies and, with some variants of the virus, it may occur without rhinorrhea or nasal congestion.48 A prospective cohort study (n = 129) conducted over 18 months found recovery occurred for most patients by seven days, and more than 80% recovered by three months. The severity of the initial dysfunction and degree of improvement in the first seven days predicted earlier resolution of smell and taste dysfunction after COVID.49 Most studies examining intranasal corticosteroid treatment for post-COVID olfactory dysfunction did not show a benefit. A Cochrane systematic review of interventions for preventing persistent post-COVID olfactory dysfunction found “very limited evidence available.”50

HEAD TRAUMA

Olfactory dysfunction after head trauma is common, and the evaluation should include imaging and specialty consultation. The anatomic location and nerve fibers that extend from the olfactory bulb near the cribriform plate are vulnerable. Besides direct trauma, shearing of olfactory fibers can also occur with coup-contrecoup injury. Posttraumatic olfactory disorders often have MRI findings of reduced olfactory bulb volume that correlate with the severity of the disorder. Postoperative olfactory or gustatory dysfunction may occur if the surgical location is near relevant anatomic structures.8,16 Recovery of olfactory function after trauma ranges from 10% to 35% but is less common than after infection and depends on the severity or location of the trauma.

SMOKING

After smoking cessation, olfactory function takes 15 years to return to levels consistent with nonsmokers. The mechanisms by which smoking impairs olfaction have not been definitively identified. Vascular mechanisms may play a role because the risk of coronary heart disease and vascular death in former smokers takes a similar amount of time to resolve to nonsmoker levels (15 and 20 years, respectively).51

The effect of secondhand smoke exposure on olfactory function is inconsistent. A prospective, case-control study comparing olfactory function in adults younger than 65 years found that olfactory function was similarly worse in people who smoke and those passively exposed to smoke, compared with nonsmokers without passive exposure.52 A cross-sectional analysis of 201 children six to 11 years of age showed no difference in olfaction among those with or without smoking parents.53

NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

Family physicians should consider evaluating patients for neurodegenerative diseases when they present with olfactory or gustatory dysfunction without an apparent etiology (Table 6).10 Changes in olfaction can serve as an early warning sign of idiopathic Parkinson disease, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer dementia and are associated with increased mortality in older people.4,10,54–56 Disease severity in Parkinson and Alzheimer disease correlates with the severity of smell and taste loss.57,58 More than 95% of patients with Parkinson disease have smell impairment, and up to 75% have anosmia or hyposmia.10 Olfactory changes can precede the motor symptoms of Parkinson disease by four to six years. Olfactory dysfunction and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are also associated and can be prodromes of Parkinson disease.10 In mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia, more dysfunction is noted on objective testing than in subjective reports from patients.4 Deterioration of smell and taste often precedes cognitive deficits.59,60

| Idiopathic Parkinson disease |

| Alzheimer dementia |

| Lewy body dementia |

| Familial Parkinson disease |

| Multisystemic atrophy |

| Huntington disease |

| Wilson disease |

| Friedreich ataxia |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia (types 2 and 3) |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

MEDICATIONS

Loss of taste and smell is an adverse effect of many medications.18,61 Loss of taste and smell attributed to medication accounts for 12% of olfactory dysfunction, and a greater proportion of gustatory dysfunction may be related to medication.37 Xerostomia can impair the transmission of tastants to taste buds. Medication-induced loss of smell or taste may be reversible if the medication is discontinued.37,62

Olfactory and Taste Training

Olfactory training should be offered to patients with persistently poor quality of life due to olfactory dysfunction.63–65 Two systematic reviews that included 3,173 patients with postviral olfactory dysfunction found that olfactory training yields objectively measured, clinically significant improvement in olfaction.43,63 Two other meta-analyses showed objective improvement in nonviral olfactory dysfunction after olfactory training.64,65 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 articles examining olfactory training found that 36% of patients with posttraumatic olfactory dysfunction had clinically significant improvement in measured olfaction.66 One randomized controlled trial (n = 138) found that adding budesonide nasal irrigation to olfactory training in patients without a visible sign of sinonasal inflammation yielded clinically significant improvement in olfaction (odds ratio = 3.93; 95% CI, 1.20 to 12.88).67 Another randomized controlled trial (n = 42) found taste sensitivity improved after three days of taste training.68 Table 7 provides olfactory training instructions.69

| Perform the following twice daily (ideally before a meal) for at least four to six months: |

| Use essential oils soaked in cotton, or liquid (around 50 mL) in an amber sniffing jar. |

| Use the following recommended scents initially: rose, eucalyptus, lemon, and clove. |

| Smell the first scent for 15 to 20 seconds; while smelling, focus on what you remember it smelling like. |

| Rest for 10 seconds. |

| Repeat as above for each scent separately. |

| Every one to three months consider changing, or adding, scents, such as menthol, thyme, tangerine, jasmine, green tea, bergamot, rosemary, gardenia; any scent of your choosing; consider scents you wish to smell again that you cannot smell now. |

Patient Education

Physicians should address safety and occupational issues with their patients because hazardous events occur two to three times more often in people with olfactory dysfunction.70 Patients who work with chemicals may have a reduced ability to identify toxic exposure and should consider mitigation strategies. All patients should take extra care to adhere to expiration dates on food, and to ensure smoke or fire and natural gas or propane alarms are operational.3,40 Some patients who are dysosmic may benefit from loved ones' assistance in identifying personal hygiene gaps. Patients and family members may benefit from a support network, such as the Smell and Taste Association of North America (https://thestana.org).

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Malaty and Malaty,4 and Bromley.71

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries and the MeSH database using the key terms ageusia, anosmia, assessment, dysgeusia, olfactory disorders, parosmia, smell, taste, taste disorder, test, questionnaire, smoke, survey, and COVID-19. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, books, and systematic reviews. The Cochrane database and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: July 31, 2022; October 5, 2022; October 20, 2022; and July 2, 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.