Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(3):249-258

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common condition of pregnancy with increasing prevalence in the United States. GDM increases risks of complications, including operative delivery, hypertensive disorders, shoulder dystocia, fetal macrosomia, large-for-gestational-age infants, neonatal hypoglycemia, and neonatal respiratory distress. In patients who are overweight or obese, prepregnancy weight loss and lifestyle modifications during pregnancy may prevent GDM. First-trimester screening can identify preexisting diabetes and early-onset GDM for prompt implementation of glucose control measures. Treatment of GDM has been shown to reduce the risk of complications and should start with lifestyle modifications. For patients who are unable to maintain euglycemia with lifestyle modifications alone, insulin is the recommended first-line medication. For patients with poor glucose control or who require medications, fetal surveillance is suggested starting at 32 weeks of gestation. For all patients with GDM, physicians should assess for fetal macrosomia (estimated fetal weight more than 4,000 g) and discuss the risks and benefits of prelabor cesarean delivery if the estimated fetal weight is more than 4,500 g. Delivery during the 39th week of gestation may provide the best balance of maternal and fetal outcomes. The recommended delivery range for patients controlling their glucose levels with lifestyle modifications alone is 39/0 to 40/6 weeks of gestation, and the ideal range for those controlling glucose levels with medications is 39/0 to 39/6 weeks of gestation. Practice patterns vary, but evidence suggests that glucose management during labor can safely include decreased glucose testing and sliding-scale dosing of insulin as an alternative to a continuous intravenous drip. Insulin resistance typically resolves after delivery; however, patients with GDM have an increased risk of developing overt diabetes. Continued lifestyle modifications, breastfeeding, and use of metformin can reduce this risk.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is glucose intolerance that is first recognized during pregnancy and suggests underlying beta cell dysfunction.1 GDM affects up to 1 in 11 pregnancies in the United States.2 As rates of inactivity, overweight/obesity, and advanced maternal age have increased, so has the incidence of GDM, which nearly doubled from 2006 to 2017.3 GDM increases the risk of numerous obstetric complications, including operative delivery, hypertensive disorders, shoulder dystocia, fetal macrosomia (estimated fetal weight more than 4,000 g), large-for-gestational-age (LGA) infants (those above the 90th percentile in weight for gestational age), neonatal hypoglycemia, and respiratory distress. Adequate glucose control reduces many of these risks.3 Patients requiring only lifestyle changes to achieve euglycemia are designated as having A1GDM, whereas those requiring medications are designated as having A2GDM.4

| As rates of inactivity, overweight/obesity, and advanced maternal age have increased, so has the incidence of GDM, which nearly doubled from 2006 to 2017. |

| A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials and 13 observational studies found no difference in large-for-gestational-age infants between one-step and two-step GDM screening methods, but patients screened with the one-step method experienced higher rates of hypoglycemia and infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. The one-step method results in twice as many GDM diagnoses without improving neonatal or maternal outcomes. |

| A meta-analysis of 17 studies found that, compared with insulin, metformin leads to lower rates of macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, neonatal intensive care unit admission, cesarean delivery, and pregnancy-induced hypertension in patients with GDM. |

Prevention

Studies examining weight changes among pregnancies suggest that even a preconception decrease in body mass index (BMI) of only 1 kg per m2 reduces the risk of developing GDM.5 Although prepregnancy weight loss appears to be effective, weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended due to the risk of small-for-gestational-age infants.6 A Cochrane review of interventions during pregnancy concluded that receiving lifestyle advice and exercising can reduce the risk of GDM, but either intervention alone is not effective.7 Additionally, this review noted only low-quality evidence supporting the use of vitamin D and myo-inositol for GDM prevention.7 High‐quality studies are needed to investigate the effect of myo‐inositol, vitamin D, probiotics, metformin, and dietary and exercise interventions on the development of GDM.

Screening

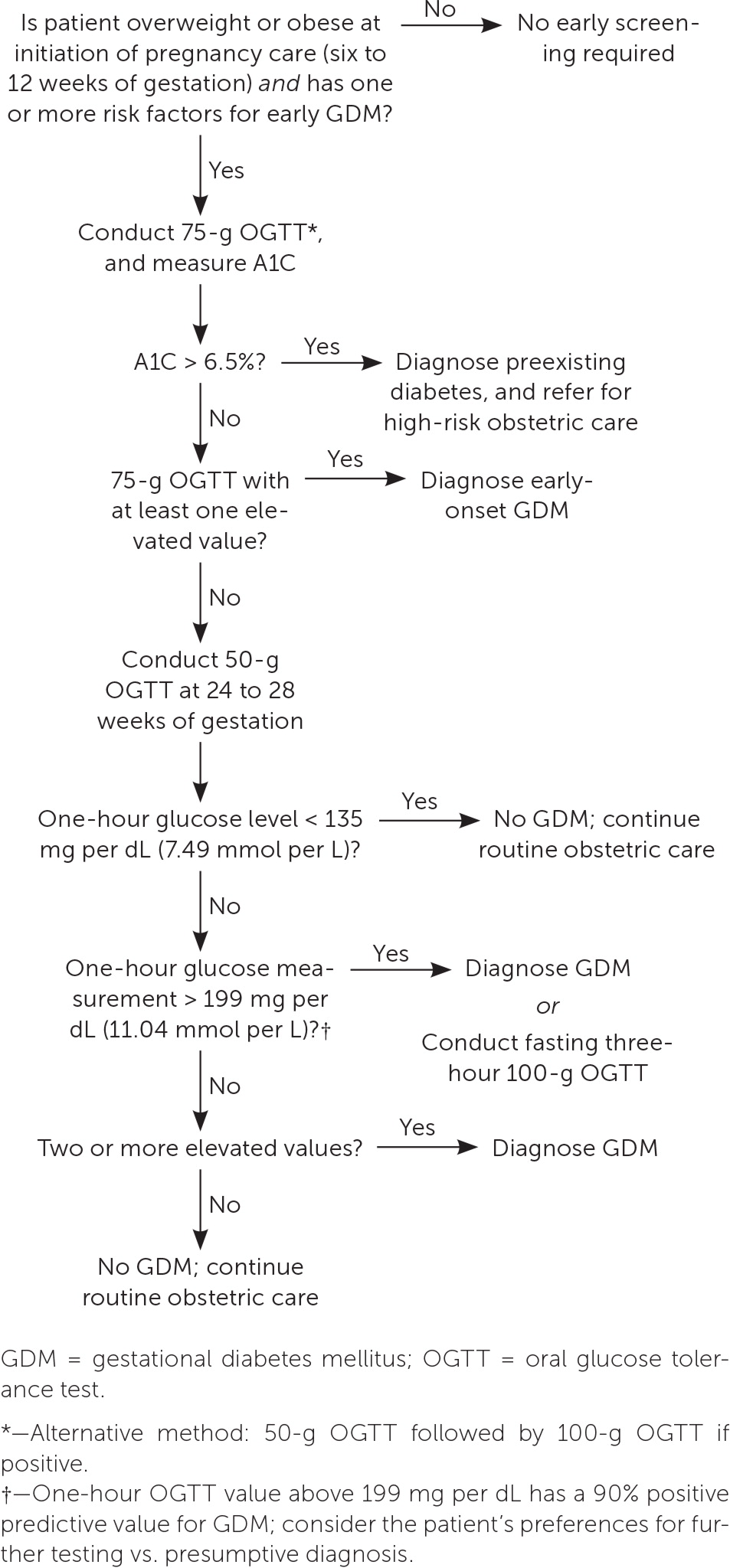

Screening for GDM in pregnant patients without known diabetes is recommended at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation.1,2,4 Retrospective observational studies of second-trimester screening have shown that it reduces the risk of cesarean delivery, birth injury, stillbirth, and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit.2 Repeat screening during pregnancy is not generally recommended but may be warranted if a high-risk condition such as polyhydramnios develops.8 Recommended screening options include the one- and two-step methods, which are similarly effective.4,9

The one-step method consists of a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with glucose measurements after one and two hours. Diagnostic criteria for the 75-g OGTT are set by the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group; a positive result requires only one abnormal value.10

The two-step method consists of a 50-g OGTT with a glucose measurement after one hour. If the result is elevated, a diagnostic fasting 100-g OGTT is conducted, with glucose measurements each hour for three additional hours.4,10 For the initial 50-g OGTT, a positive result varies between 130 and 140 mg per dL (7.21 to 7.77 mmol per L), with institution-specific cutoffs.4 A threshold of 135 mg per dL (7.49 mmol per L) has 93% sensitivity and 79% specificity; this is similar to the specificity of the 140 mg per dL threshold (82%).2 For patients with one-hour glucose values of greater than 199 mg per dL (11.04 mmol per L), forgoing the confirmatory 100-g OGTT and presumptively treating for GDM can be considered.11 The Carpenter-Coustan criteria or the National Diabetes Data Group threshold can be used to determine abnormal 100-g OGTT values. GDM is diagnosed if the measurement has two values at or above the chosen threshold, but even an elevation of one value may indicate increased risk of associated complications.4

Additionally, a meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials and 13 observational studies found no difference in LGA infants between one-step and two-step methods, but patients screened with the one-step method experienced higher rates of hypoglycemia and infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit compared with those screened with the two-step method.12 The one-step method results in twice as many GDM diagnoses as the two-step method and may be more cost-effective. However, it has not been shown to consistently improve neonatal or maternal outcomes despite being the approach most often used globally.2,12,13 Although either screening method is acceptable, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends the two-step method for screening at or after 24 weeks.4

Patients unable to tolerate oral glucose testing, including patients with a history of malabsorptive gastric bypass surgery, can be screened by recording a one- to two-week diary of fasting and postprandial capillary glucose levels.14 However, there is no standard threshold for establishing a diagnosis using glucose diary values.14

| Test method | Glucose threshold | |

|---|---|---|

| One-step method | ||

| 75-g OGTT | International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group | |

| Fasting | 92 mg per dL (5.11 mmol per L) | |

| One hour | 180 mg per dL (9.99 mmol per L) | |

| Two hour | 153 mg per dL (8.49 mmol per L) | |

| Two-step method | ||

| 50-g OGTT | Use institutional thresholds | |

| One hour | 130 to 140 mg per dL (7.21 to 7.77 mmol per L) | |

| 100-g OGTT | Carpenter-Coustan | National Diabetes Data Group |

| Fasting | 95 mg per dL (5.27 mmol per L) | 105 mg per dL (5.83 mmol per L) |

| One hour | 180 mg per dL | 190 mg per dL (10.54 mmol per L) |

| Two hour | 155 mg per dL (8.6 mmol per L) | 165 mg per dL (9.16 mmol per L) |

| Three hour | 140 mg per dL | 145 mg per dL (8.05 mmol per L) |

| Self-monitoring (if unable to perform OGTT) | ||

| Fasting | 95 mg per dL | |

| One hour postprandial | 140 mg per dL | |

| Two hours postprandial | 120 mg per dL (6.66 mmol per L) | |

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concludes that there is insufficient evidence to recommend universal testing for abnormal glucose tolerance in early pregnancy, but some patients may benefit from first-trimester screening.2 Retrospective studies show that patients with preexisting diabetes and early-onset GDM have higher rates of LGA infants, hypertensive disorders, cesarean delivery, and congenital malformations.2,16,17 A recent prospective study of more than 40,000 patients found that early screening and treatment of GDM in patients who are obese decrease the risk of LGA infants and cesarean delivery.18 ACOG and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommend considering screening high-risk patients early in pregnancy.1,4

Age 35 years or older

BMI of 25 kg per m2 or greater (23 kg per m2 or greater in Asian people [studies show greater risk of adverse health outcomes at lower BMI in people of Asian ancestry; however, the reasons for this risk and variation among patients in Asian subgroups require further investigation19]); consider performing early glucose screening for patients with this risk factor and one or more additional risk factor

BMI 40 kg per m2 or greater; this risk factor alone may warrant testing

First-degree relative with diabetes

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol level less than 35 mg per dL (0.91 mmol per L) or triglyceride level greater than 250 mg per dL (2.82 mmol per L)

History of cardiovascular disease, impaired fasting glucose (this single risk factor may warrant testing), delivering an infant with macrosomia (birth weight 4,000 g or greater), or GDM

HIV

Hypertension

Inactivity

Taking a medication associated with develop -ment of diabetes, such as atypical antipsychotics or corticosteroids

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Race/ethnicity such as Native American, African American, Latino, Asian American, Pacific Islander (causal factors for race and ethnicity as a risk factor are complex and not fully understood and should not be assumed to be due to genetics alone)

Signs of insulin resistance, such as acanthosis nigricans

The best screening test for abnormal glucose tolerance in early pregnancy is not clear. A1C level, fasting glucose level, or the one- or two-step method can be used4 (Table 21,4,10,15,20–22,25). Although the 2023 ADA guidelines recommend obtaining an A1C or fasting glucose measurement before 15 weeks of gestation to diagnose preexisting diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance, the biophysical changes of early pregnancy reduce the sensitivity to detect diabetes.1,23,24 A prospective randomized controlled trial of first-trimester testing to predict GDM found that compared with the two-step method or measurement of fasting plasma glucose, the one-step method has better sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value.23 For patients with normal early glucose screening results, testing should be repeated between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation.1,4 An approach to GDM screening is presented in Figure 1.1,4,10,11,14,21

| Test | Normal range | Impaired glucose tolerance/early GDM | Preexisting diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1C* | < 5.9% | 5.9% to 6.4% | ≥ 6.5% |

| Fasting plasma glucose | < 110 mg per dL (6.11 mmol per L) | 110 to 125 mg per dL (6.11 to 6.94 mmol per L) | ≥ 126 mg per dL (6.99 mmol per L) |

| 75-g OGTT | Fasting plasma glucose: < 92 mg per dL (5.11 mmol per L) One hour: < 180 mg per dL (9.99 mmol per L) Two hour: < 153 mg per dL (8.49 mmol per L) | Fasting plasma glucose: 92 to 125 mg per dL (5.11 to 6.94 mmol per L) Onehour: ≥ 180 mg per dL Two hour : ≥ 153 mg per dL | Fasting plasma glucose: ≥ 126 mg per dL |

Treatment

General dietary recommendations include a minimum daily intake of 175 g complex carbohydrates, which is approximately 35% of a 2,000-calorie diet.4,25 The ADA recommends individualized nutrition planning with a registered dietitian.25 A Cochrane review found that no diet was clearly superior for GDM, but noted a reduction in cesarean delivery rate with the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet in two trials with 86 patients.31

With GDM, exercise improves fasting and postprandial glucose control, but the effects on patient-centered outcomes are unknown.32–34 Combining diet and exercise interventions reduces the risk of LGA infants.34,35 Higher maternal age, BMI, and fasting blood glucose levels and earlier gestational age at diagnosis reduce the likelihood that glucose can be controlled by lifestyle modifications alone.36

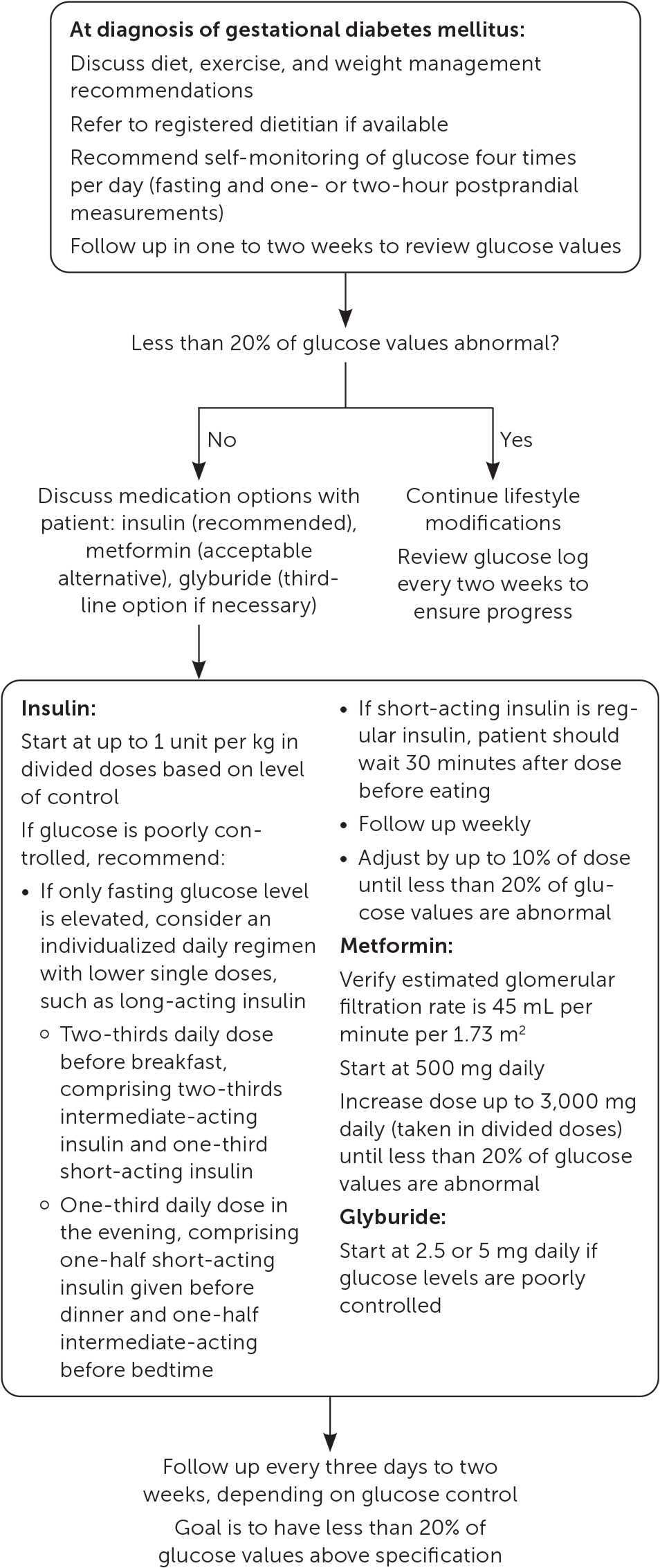

Daily glucose monitoring typically consists of measuring the fasting glucose value and three postprandial values, reviewed weekly. Consensus thresholds for hyperglycemia in pregnancy include more than 95 mg per dL (5.27 mmol per L) fasting, more than 140 mg per dL one hour post-prandial, and more than 120 mg per dL (6.66 mmol per L) two hours postprandial.4,25 There is no consensus regarding when pharmacotherapy is necessary to control glucose levels; recommended thresholds range from a single abnormal value to a week of 50% abnormal values.4,26,37 A reasonable approach is to start pharmacotherapy when more than 20% of glucose values are abnormal or when there are more than five abnormal values in seven days of careful monitoring. One small, retrospective study found that initiating pharmacotherapy when 20% to 40% of glucose measurements are abnormal improves neonatal outcomes compared with starting medications when 40% or more of glucose measurements are abnormal.26

Measuring fetal growth via ultrasonography as an adjunct to glucose control does not appear to improve rates of neonatal hypoglycemia, cesarean delivery, shoulder dystocia, LGA infants, or overall neonatal morbidity.38 Fetal echocardiography at 18 to 22 weeks of gestation should be considered for patients with early-onset GDM because the condition is associated with a higher risk of cardiac defects.39,40

Glucose control cannot be achieved with lifestyle modifications alone in 30% of patients.27 When pharmacologic management is needed, ACOG and the ADA primarily recommend insulin due to its long-standing safety profile, effectiveness, and inability to cross the placenta.4,25 The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommends considering metformin for its clinical effectiveness and cost, and if the patient prefers it.27 Although previous meta-analyses suggested that use of metformin is equivalent to insulin in reducing of rates of LGA infants, macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia, recent studies suggest improved outcomes with metformin.41–45 A 2021 meta-analysis of 17 studies found that, compared with insulin, metformin leads to lower rates of macrosomia (relative risk [RR] = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.88), neonatal hypoglycemia (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.80), neonatal intensive care unit admission (RR = 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.91), cesarean delivery (RR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.90), and pregnancy-induced hypertension (RR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.27 to 0.83).44 Because metformin crosses the placenta, there is some concern about the long-term effects of in utero exposure. No difference in neurodevelopmental outcomes has been found in elementary school children exposed to metformin in utero.46–48 Systematic reviews demonstrate significantly increased weight in children exposed to metformin in utero, without a significant difference in BMI.46,49

Glyburide can be considered for glucose control in patients who are unable or prefer not to take insulin or metformin.4,25 Like metformin, glyburide crosses the placenta, and the long-term developmental impact of in utero exposure is unknown. Although glyburide is equivalent to metformin for glucose control during pregnancy, it increases the risk of neonatal hypoglycemia and may increase the risk of preeclampsia, neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, and stillbirth.4,25,44,50

Insulin is often prescribed in multiple divided doses of short-, intermediate-, and long-acting analogues. For those with only fasting hyperglycemia, single daily doses may be appropriate.4 A Cochrane review did not find any differences among various insulin types and dosage strategies.43 Starting at 0.7 to 1 unit of insulin per kg per day should be considered for patients with persistent hyperglycemia.4 Asymptomatic hypoglycemia is uncommon in GDM; therefore, titrating the dose of insulin (up to 10% increments every two or three days) is reasonable with close patient follow-up.28

Fetal Surveillance

The risk of stillbirth after 36 weeks of gestation is increased in patients with GDM to 17 per 10,000 births, compared with 13 per 10,000 births in patients without GDM.51 Antepartum fetal surveillance includes several noninvasive approaches to detect risk of stillbirth, with no specific testing strategy showing superiority (Table 3).52 Due to the increased rate of stillbirth, surveillance once or twice weekly beginning at 32 weeks of gestation is suggested for patients with poor glycemic control or who require medications.53 The benefit of fetal surveillance for patients who manage GDM with lifestyle modifications is less clear. The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine has a Choosing Wisely recommendation against performing antepartum fetal surveillance in patients who have appropriate glucose control via dietary modifications alone unless additional indications arise.54

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| Biophysical profile | 20-minute fetal heart rate tracing plus ultrasonography, assigning points for fetal movement, tone, breathing, and single deepest vertical amniotic fluid pocket > 2 cm |

| Contraction stress test | 10-minute fetal heart rate tracing with at least three contractions |

| Maternal-fetal movement assessment | Maternal perception of 10 fetal movements, up to two hours |

| Modified biophysical profile | Nonstress test and ultrasound identification of single deepest vertical amniotic fluid pocket > 2 cm |

| Nonstress test | 20-minute fetal heart rate tracing |

| Umbilical artery doppler velocimetry | Ultrasonic assessment of vascular resistance typically used in growth-restricted fetuses |

Delivery for Patients With GDM

TYPE OF DELIVERY

ACOG recommends that physicians discuss the potential risks and benefits of prelabor cesarean delivery for patients with GDM when estimated fetal weight is more than 4,500 g.4,55 Patients with GDM are twice as likely to have a macrosomic fetus, increasing the risk of shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, and cesarean delivery.55 Ultrasound biometry is the main method for estimating fetal weight, but it has only a 56% sensitivity in predicting macrosomia.56 Serial ultrasound growth measurements are often performed but may not improve sensitivity in predicting fetal macrosomia compared with a single study performed in the late third trimester.57 The limited accuracy of estimated fetal weight in predicting brachial plexus injury means that more than 500 cesarean deliveries may be needed to prevent one case of permanent fetal neurologic insult.58

DELIVERY TIMING

Delivery for patients with well-managed GDM is not recommend before 39 weeks of gestation.4 A large, retrospective study showed that induction of labor before 40 weeks of gestation in patients with GDM decreases rates of cesarean delivery and hypertensive disorders.59 Induction before 39 weeks of gestation reduces rates of shoulder dystocia but increases rates of neonatal hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and neonatal intensive care unit admission.59 Several small trials demonstrate that induction before 39 weeks of gestation increases neonatal morbidity.60,61 If glucose control remains poor despite medications, delivery prior to 39 weeks may be considered in consultation with specialists. 4,62 ACOG recommends delivery in the 39th or 40th week of gestation for patients with diet-controlled GDM and during the 39th week of gestation for patients with medication-controlled GDM.62

INTRAPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Intrapartum management of GDM is largely extrapolated from data on patients with preexisting diabetes, which suggests that glucose levels should be maintained between 70 and 110 mg per dL (3.89 to 6.11 mmol per L).25,30 Patients with diet-controlled GDM may be less likely to develop hyperglycemia in labor, but evidence is lacking.63 A retrospective study of 3,680 infants of mothers with GDM or type 1 or 2 diabetes demonstrated no association between maternal intrapartum glucose levels and neonatal hypoglycemia after adjusting for neonatal size, gestational age, and sex.64 Additional studies have found inconsistent improvement in fetal hypoglycemia with intrapartum maternal glucose control, suggesting intrapartum maternal glucose may play a smaller role in immediate neonatal glucose control than previously thought.65–67

Depending on the planned time of induction, patients taking insulin can reduce or discontinue their morning dose.30 Maternal glucose monitoring is typically checked hourly during active labor, but one study showed similar rates of neonatal hypoglycemia with measurement once every four hours.68 Glucose control can be achieved with continuous administration of insulin, rotating fluids with dextrose and insulin, or with protocols that include administration of insulin on a sliding scale.67–69

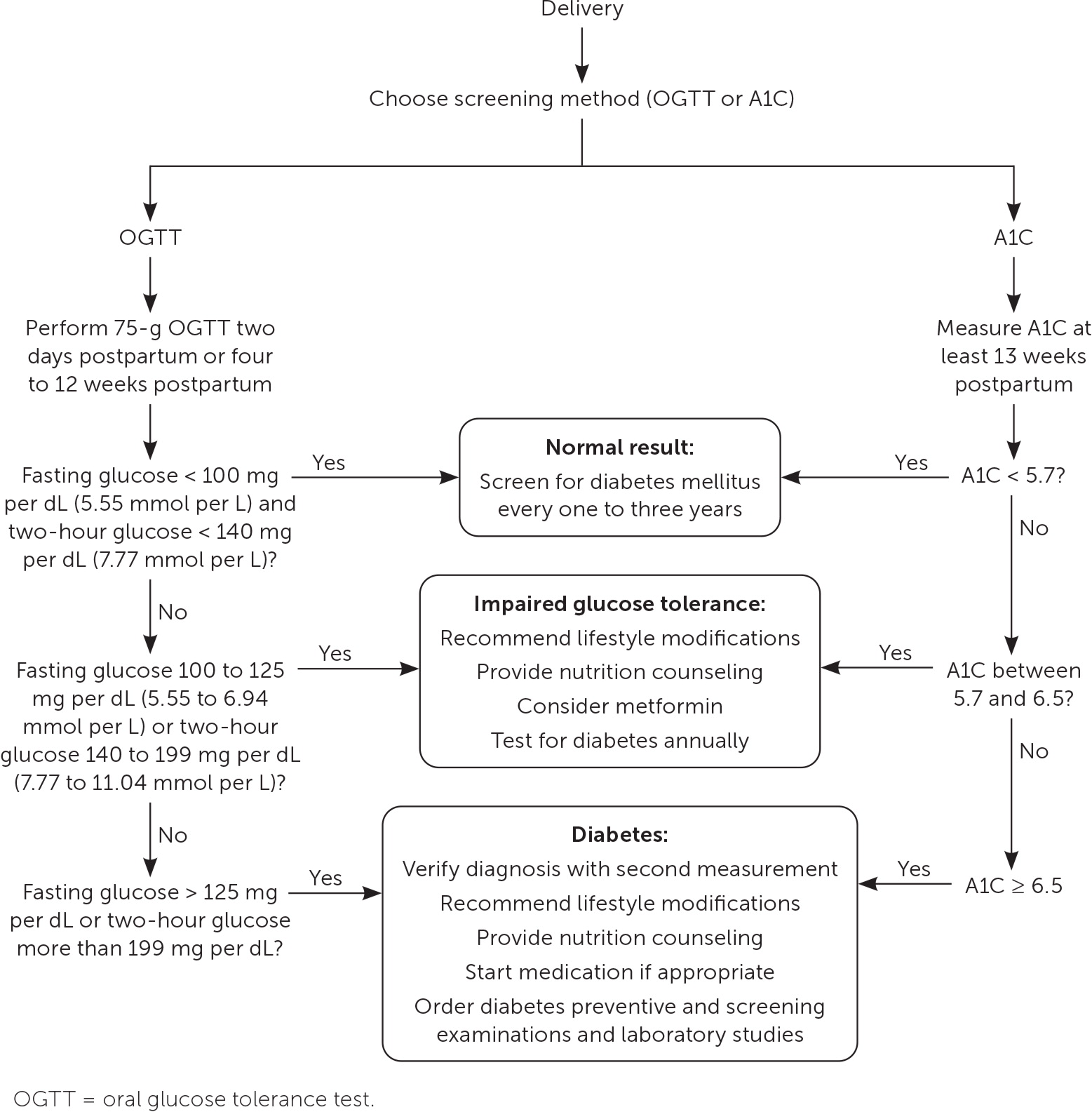

Postpartum

Following delivery, maternal glucose levels typically return to prepregnancy values. However, the risk of developing overt diabetes within 25 years is 10 times higher in patients who have a history of GDM compared with those who do not.70 ACOG and the ADA recommend a two-hour OGTT performed four to 12 weeks postpartum to screen for persistently abnormal glucose control (Figure 32,4,25,71). Only 35% of patients complete this testing due to barriers such as lack of knowledge of guidelines, provider-to-provider and provider-to-patient communication errors, lack of insurance coverage, and not being present for postpartum follow-up.4,25,72

Alternative postpartum screening methods include a two-hour 75-g OGTT on the second day postpartum, a fasting glucose assessment before 13 weeks postpartum, and an A1C measurement at least 13 weeks postpartum.73–76 The two-hour OGTT and A1C measurement are as reliable at predicting diabetes at one year postpartum as the two-hour OGTT performed at four and 12 weeks.72,73,77 A prospective cohort study of 300 patients found that a 75-g OGTT performed on the second day postpartum is as accurate at detecting diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance as testing at four to 12 weeks.74

Breastfeeding may protect against future development of diabetes and should be encouraged.77,78 A meta-analysis of 17 studies found that patients with a history of GDM who do not breastfeed have higher blood glucose levels and a greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with those who do breastfeed.78

For patients with postpartum impaired glucose tolerance, treatment can reduce progression to type 2 diabetes. Intensive lifestyle modifications reduce the risk of diabetes over 10 years, with a number needed to treat of 12 compared with placebo. Metformin is more effective in preventing progression to diabetes, with a number needed to treat of 8 over 10 years compared with placebo.71 Due to the high lifetime risk of GDM, patients with normal postpartum test results should have follow-up testing performed at least every one to three years.4,25

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the term gestational diabetes. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, reviews, and guidelines. The Cochrane database, ACOG, DynaMed, and UpToDate were also searched. Whenever possible, studies using race as a primary factor that did not define how these categories were assigned were excluded from the final review. Search dates: April 30 to September 23, 2022; December 7, 2022; January 13, 2023, and July 24, 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.