Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(6):580-587

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Pelvic masses occur in up to 20% of women throughout their lifetime. These masses represent a spectrum of gynecologic and nongynecologic conditions. Adnexal masses—found in the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and surrounding areas—are mostly benign. Evaluation includes assessment for symptoms that may suggest malignancy, such as abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, and early satiety. A family history of ovarian, breast, or certain heritable syndromes increases the risk of malignancy. For women of reproductive age, ectopic pregnancies must be considered; a beta human chorionic gonadotropin level should be obtained. Transvaginal ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice for evaluating adnexal masses for size and complexity. Adnexal cysts that are greater than 10 cm, contain solid components, or have high color flow on Doppler ultrasonography are high risk for malignancy. Further imaging, if warranted, should be completed with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, particularly if there is concern for disease outside the ovary. Multimodal assessment tools that use ultrasonography and biomarkers, such as the risk of malignancy index, are useful in the diagnosis and exclusion of malignant causes. Asymptomatic masses that are determined to be benign may be observed and managed expectantly. In symptomatic or emergent cases, such as ectopic pregnancy or ovarian torsion, a gynecologist should be consulted. In any adnexal mass with high risk for malignancy, a consultation with gynecologic oncology is indicated.

Pelvic masses occur in up to 20% of women during their lifetime and can arise from gynecologic or nongynecologic etiologies.1,2 The adnexa are a group of structures adjacent to the uterus, which includes the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Although the most common sources of adnexal masses are benign, such as luteal cysts and polycystic ovaries, masses can also have malignant causes, such as epithelial ovarian carcinoma or other cancers metastatic to the ovary. Potentially fatal adnexal masses include ectopic pregnancies, pelvic inflammatory disease, and tubo-ovarian abscesses3–6 (Table 14–7). This article reviews the evaluation and management of adnexal masses in women and other people assigned female sex at birth.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not screen for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women at average risk. | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| Do not perform pelvic ultrasonography in average-risk women to screen for ovarian cancer. | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| Do not screen low-risk women with cancer antigen 125 levels or ultrasonography for ovarian cancer. | Society of Gynecologic Oncology |

| Do not perform pelvic examination on asymptomatic nonpregnant women, unless necessary for guideline-appropriate screening for cervical cancer. | American Academy of Family Physicians |

| Condition | Suggestive symptoms | Possible examination findings | Possible ultrasound findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign cystic mature teratoma | Lower abdominal pain, but often asymptomatic | Adnexal mass or tenderness | Hyperechoic mass with acoustic shadow, dermoid mesh; may have solid component representing teeth or bone |

| Ectopic pregnancy | Lower abdominal (usually unilateral and severe) or pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding | Adnexal mass or tenderness, hypotension, tachycardia | Empty uterine cavity with thick echogenic endometrium; free pelvic fluid, complex extra adnexal cyst, or tubal ring sign |

| Endometrioma | Abnormal uterine bleeding, dyspareunia, worsening pain with menses | Adnexal mass or abdominal tenderness, tenderness over uterosacral ligaments | Chocolate-colored fluid-filled cyst, uni- or multiloculated, diffuse low-level homogenous echoes (ground-glass appearance) |

| Functional ovarian cyst (corpus luteum cyst) | Unilateral pelvic pain, pain during middle of menstrual cycle (mittelschmerz), pain with intercourse | Adnexal mass or tenderness | Thin wall, unilocular, < 3 cm, no papillary projections |

| Hydrosalpinx | Pelvic pain, infertility | Adnexal mass or tenderness | Tubular, elongated cystic mass with incomplete septations |

| Leiomyoma | Heavy menstrual bleeding, dysmenorrhea | Uterine enlargement, abdominal mass | Well-defined solid concentric hypoechoic masses with acoustic shadowing; calcifications may be present |

| Ovarian cancer | Pelvic or abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, bloating, pressure, early satiety, difficulty eating, increased abdominal size, indigestion, dyspareunia, urinary urgency or frequency, incontinence | Abdominal or adnexal mass, ascites, pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy, nodularity of uterosacral ligaments | Adnexal mass > 10 cm, papillary or solid components, high color flow on Doppler imaging, presence of ascites |

| Ovarian torsion | Sudden onset, severe, unilateral pelvic or lower abdominal pain, often with associated nausea and vomiting | Abdominal or adnexal tenderness | Enlarged ovary with peripheral follicles, free pelvic fluid, classically presents with decreased blood flow on Doppler imaging |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease or tubo-ovarian abscess | Fever, pelvic or lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, nausea, vomiting | Abdominal or adnexal tenderness, cervical motion tenderness, fever, vaginal discharge | Complex cyst with thick walls and seemingly solid areas that may have adjacent pyosalpinx |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | Oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, or heavy menstrual bleeding associated with obesity and hyperandrogenism | Unilateral or bilateral adnexal fullness or enlarged ovary or ovaries | Increased follicle number per ovary, ovarian enlargement |

Ovarian cancer is the second most common type of female reproductive cancer in the United States.8 Ovarian cancer causes 2.5% of all cancer in women and has a five-year survival rate of 50%.9,10 Survival rates are even lower among Black women, and, because these disparities persist after correcting for socioeconomic status, the rates may represent systemic racism.11,12

Screening

Screening for ovarian cancer is not recommended. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends against screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women who are not high risk because of the lack of mortality benefit and high false-positive rates in randomized controlled trials evaluating the cancer antigen (CA) 125 level, transvaginal ultrasonography, and bimanual pelvic examination.13,14 The high false-positive rate can lead to significant harms, including unnecessary invasive procedures and postoperative complications.14 The American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians recommend against pelvic examination screening.15–18 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening with bimanual examinations in asymptomatic, nonpregnant patients.13

History

Adnexal masses can present with a variety of subtle symptoms. Abdominal and pelvic pain are the most common symptoms noted by premenarchal patients with an adnexal mass, including those with urgent etiologies.19 Common symptoms that are concerning for malignancy are vague, and the physician must maintain a high level of suspicion when evaluating women presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms such as early satiety, abdominal bloating, unintended weight loss, or urinary symptoms (e.g., frequency, urgency, incontinence). These symptoms, especially if present daily for more than two weeks or not responsive to appropriate treatment, should prompt further evaluation.20 If ovarian cancer is suspected, symptoms commonly associated with ovarian malignancy should be assessed (Table 23,21).

| Symptom | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal bloating | 33 to 70 | 62 to 99 |

| Abdominal pain | 50 to 84 | 70 to 88 |

| Difficulty eating | 20 | 100 |

| Early satiety | 58 | 97 |

| Increased abdominal size | 49 to 64 | 81 to 98 |

| Pelvic pain | 7 to 41 | 70 to 84 |

| Four or more symptoms | 27 | 96 |

A review of risk factors can aid in diagnosis. Women of reproductive age should be assessed for pregnancy status and use of contraception; ectopic pregnancy presents as an adnexal mass that can be life-threatening. Special attention should be given to women with risk factors for ovarian malignancy, including nulliparity, delayed childbearing, unopposed estrogen, and obesity. A family history should be obtained, including history of ovarian or breast cancers or other heritable syndromes (e.g., Lynch syndrome) or the presence of BRCA mutation.22

Physical Examination

In patients with symptomatic or incidentally found adnexal masses, a physical examination may aid in detection of metastatic disease.2,15 However, in individuals with a body mass index greater than 30 kg per m2, identifying adnexal masses through physical examination has limited accuracy.2 Abdominal examination, which includes palpation for masses and assessment for ascites, can aid in detection of malignant disease.2 Auscultating and percussing the lungs to assess for consolidation or pleural effusion and evaluating lymph nodes may assist in detection of metastatic disease.2 A pelvic examination, including speculum, bimanual, and rectal examinations, may help characterize an adnexal mass. Any abnormalities on physical examination should be followed with imaging.

Evaluation

LABORATORY TESTING

In premenopausal patients, a serum or urine beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) level should be obtained in the initial evaluation of adnexal masses to assess for pregnancy-related conditions.2,23 A complete blood count with differential may indicate infectious etiologies (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease, tubo-ovarian abscess, other inflammatory causes, including malignancy).2

Biomarkers. Although 80% of patients with epithelial ovarian cancers have elevated CA 125 levels, one-half of patients with stage 1 disease have normal levels.24 CA 125 testing has a high false-positive rate because elevated levels are associated with multiple conditions, including pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, menstruation, and obesity25 (Table 33,25,26). In a woman with an adnexal mass and a CA 125 level greater than 35 U per mL (35 kU per L), the likelihood of a malignancy is 40% if she is postmenopausal and 13% if she is premenopausal.27

| Benign gynecologic cause |

|---|

| Adenomyosis |

| Endometriosis, especially endometrioma |

| Leiomyoma |

| Menstruation |

| Ovarian fibroma |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease |

| Pregnancy |

| Previous hysterectomy |

| Benign nongynecologic cause |

| Heart failure |

| Liver cirrhosis with or without ascites |

| Lung disease |

| Myocardial infarction |

| Obesity |

| Pancreatitis |

| Pneumonia |

| Recent surgery |

| Tuberculosis |

| Malignancy |

| Breast cancer |

| Endometrial cancer |

| Lung cancer |

| Pancreatic cancer |

| Peritoneal implants of non-ovarian cancers |

Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is elevated in 50% of patients who have ovarian cancer with normal CA 125 levels and is less frequently elevated in benign ovarian tumors and endometriosis.28 Normal values are not well established; therefore, HE4 is approved only in monitoring for recurrent or progressing epithelial ovarian cancers.28

Biomarker Panels. Panels that include multiple biomarkers, such as the risk for ovarian malignancy algorithm and multivariant index assay, are certified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for women 18 years and older who have an adnexal mass and in whom surgery is planned.2 The risk for ovarian malignancy algorithm uses serum concentrations of CA 125 and HE4 and also menopausal status to determine the likelihood of malignancy.28,29 The multivariant index assay uses five biomarkers associated with ovarian cancer to determine a malignancy risk score.30,31 Recent studies have shown that the second-generation multivariant index assay is superior to the risk for ovarian malignancy algorithm in detecting ovarian cancer.32,33

IMAGING

Transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice for adnexal masses.2 In children and in adolescents who are not sexually active and do not use tampons, transabdominal ultrasonography may be more appropriate.34 Ultrasound findings that confer high risk for malignancy include a cyst (a specific type of adnexal mass) greater than 10 cm in diameter, papillary or solid components within a cyst, irregularity, high color flow on Doppler ultrasonography, or presence of ascites.2 Benign findings include cysts with thin, smooth walls and without solid components; septations; or internal blood flow on Doppler ultrasound imaging.2

Further imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated, particularly if there is concern for disease outside the ovary.16 Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging findings such as enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes, omental caking, and ascites should raise concern for ovarian malignancy.34–36

MULTIMODAL TOOLS

The risk of malignancy index and the International Ovarian Tumour Analysis’s assessment of different neoplasias in the adnexa (ADNEX) risk model use ultrasound findings and biomarkers to risk stratify women with adnexal masses. In women with suspected ovarian malignancy, the risk of malignancy index should be calculated, although utility is limited because of a sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 92%.37 The risk of malignancy index is available as an online calculator (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10103/risk-malignancy-index-rmi-ovarian-cancer).

Serum markers, including CA 125 and HE4, can be combined with a symptom index to evaluate higher risk of ovarian cancer. Although none of these scores rule out ovarian cancer, a low value may support continued close observation and follow-up.31 The symptom index was developed for use in primary care and comprises six symptoms (Table 2).3,21 The symptom index is considered positive if symptoms have been present at least 12 times per month for less than one year. Combining a symptom index with CA 125 and HE4 (triple screen) markers has higher specificity and positive predictive value than CA 125 alone, but the combination has similar sensitivity and negative predictive value for diagnosing ovarian cancer20,31 (Table 420,38). CA 125 combined with a positive symptom index has a high sensitivity (96.4%) and negative predictive value (97.4%), with specificity and positive predictive values of 65.5% and 57.8%, respectively; this demonstrates its clinical usefulness in areas where the HE4 assay may not be available or is cost prohibitive.21,38

| Marker(s) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | LR+ | LR− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA 125 | 79 | 76 | 3.29 | 0.28 |

| HE4 | 77 | 91 | 8.56 | 0.25 |

| SI + CA 125 | 96.4 | 65.5 | 2.79 | 0.05 |

| SI + CA 125 + HE4 | 79 | 91 | 8.78 | 0.23 |

Management

PREMENARCHAL CHILDREN

Although one-half of adnexal masses in children are benign dermoid cysts, up to one-fourth of them are malignant.19,39 The most common type of malignancy in this age group is germ cell tumors, and laboratory testing that includes alpha feto-protein, beta-hCG, and l-lactate dehydrogenase levels should be obtained.2,40,41

Many adnexal masses in this age group can be managed expectantly if patients are asymptomatic and the masses appear benign on imaging. Indications for surgery include suspected torsion, persistent mass, concern for malignancy, or acute abdominal pain.4,42,43 If surgery is indicated, patients should be referred to a gynecologist, if possible, to also discuss ovarian-conserving management.39 If suspicion for ovarian malignancy occurs, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted.2 Surgical planning should involve discussion of fertility preservation, and referral to a gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist may be beneficial.44

NONPREGNANT ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS WHO ARE OF REPRODUCTIVE AGE

Ruling out ectopic pregnancy should occur first in the evaluation of adnexal masses in all patients of reproductive age. Most pregnancies are visualized on transvaginal pelvic ultrasonography at a beta-hCG level of 1,500 mIU per mL (1,500 IU per L).23 Some intrauterine pregnancies may not be visualized at this cutoff, and patients can be monitored until they reach a beta-hCG level of 3,500 mIU per mL (3,500 IU per L) to avoid misdiagnosis of intrauterine pregnancy.23 If an intrauterine pregnancy is present, the risk for simultaneous ectopic pregnancy (heterotopic pregnancy) is extremely low, occurring in 1 in 30,000.45 If an ectopic pregnancy is diagnosed, consultation with a gynecologist is indicated.

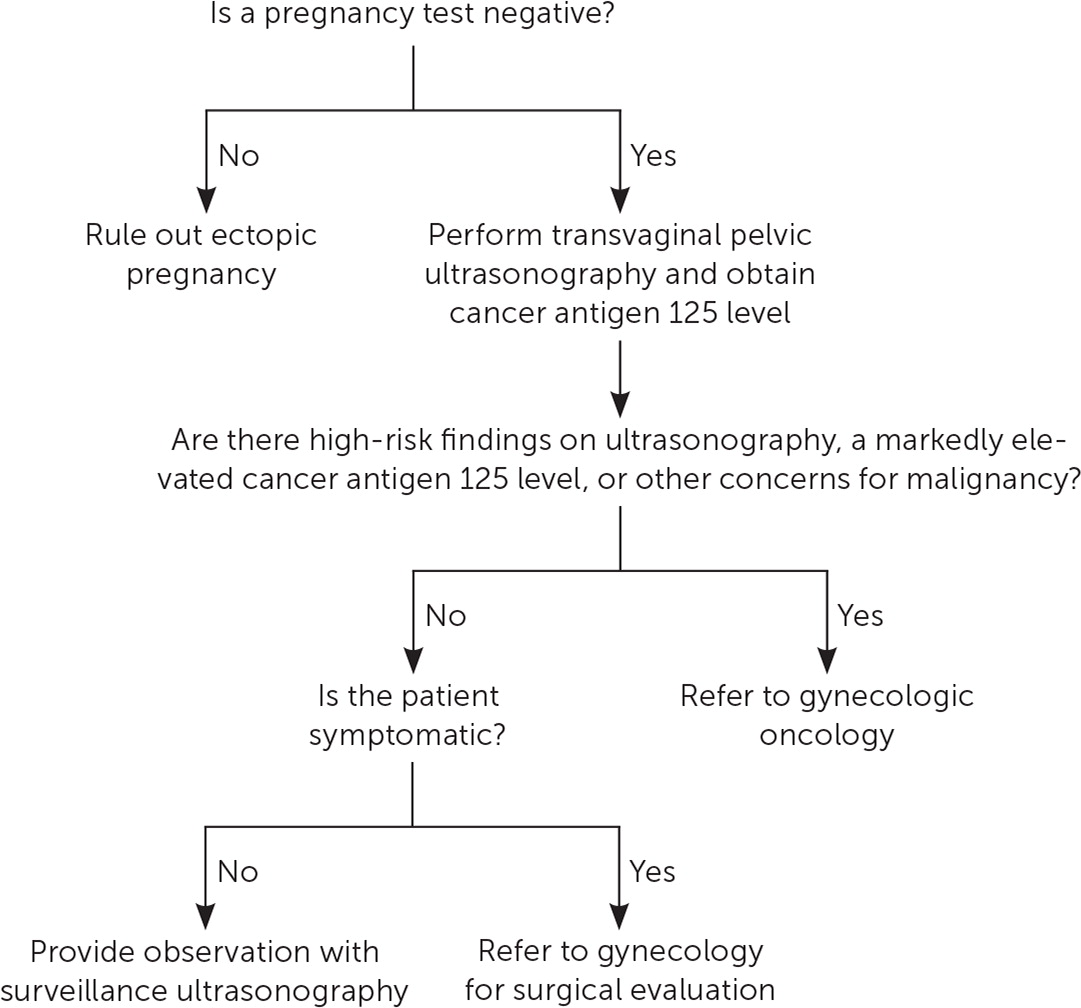

After ectopic pregnancy is ruled out, malignancy should be considered. Referral to gynecologic oncology should occur with markedly elevated CA 125 levels, high-risk ultrasound imaging findings, nodular or fixed adnexal masses, or a high score on a risk evaluation tool.2 In apparently benign masses (e.g., physiologic cyst, endometrioma, mature teratoma), expectant management is appropriate with regular surveillance imaging. Guidelines on timing of follow-up imaging are lacking.2 The evaluation of adnexal masses in females of reproductive age is discussed in Figure 1.2,22,23,38

PREGNANCY

In pregnant patients, adnexal masses are best characterized by ultrasonography. If additional imaging is warranted, magnetic resonance imaging is preferred.47 If a benign-appearing mass is detected during the first trimester, repeat imaging should occur between 18 and 20 weeks. Benign-appearing masses found in the second trimester should be further evaluated between 32 and 36 weeks, and those found in the third trimester can be evaluated during cesarean delivery (if obstetrically indicated) or six weeks postpartum.43

Surgical consultation is indicated if imaging findings suggest malignancy, the mass is increasing in size, the CA 125 level is markedly elevated (i.e., a CA 125 level greater than 35 U per mL [35 kU per L]), or the presentation suggests emergent conditions, such as ovarian torsion.42,43 Although surgery can be performed at any gestational age, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends nonurgent laparoscopic surgery be delayed to the early second trimester.48

PERIMENOPAUSAL AND POSTMENOPAUSAL ADULTS

Age is the most important risk factor for ovarian cancer. The median age of ovarian cancer diagnosis is 63 years, and 69% of cases are diagnosed at 55 years or older.2

Adnexal masses occurring in women 41 to 50 years of age are most often simple or functional cysts, whereas ovarian carcinomas most often occur in women older than 50 years.8 Any adnexal mass in this group should be evaluated using a CA 125 level and transvaginal ultrasonography. Simple cysts less than 5 cm in diameter have a low risk of malignancy, especially if asymptomatic and the serum CA 125 level is normal. These cysts typically have a physiologic cause and spontaneously resolve within six to 12 weeks.8

Endometriomas more commonly occur in perimenopausal women than in postmenopausal women, in which the risk of ovarian malignancy is three times higher.27 Dual screening using the symptom index and CA 125 level can help differentiate malignant from nonmalignant masses in perimenopausal women.

In perimenopausal women, the most common adnexal masses are functional ovarian cysts (corpus luteum cysts). In perimenopausal women, the CA 125 level is unreliable for excluding malignancy because of low specificity and frequent false-positive results. Transvaginal ultrasonography is most useful because a simple cyst makes CA 125 measurement unnecessary. Figure 2 shows the evaluation and recommended workup for adnexal masses in postmenopausal patients.2,8,27,37

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Biggs and Marks3; Givens, et al.7; and Drake.49

Data Sources: A search was completed using PubMed, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and Google Scholar. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Key search terms included adnexal mass, pelvic mass, ovarian cancer, ectopic pregnancy, CA 125, HER4, risk of ovarian malignancy, and risk of malignancy index. We critically reviewed studies that used patient categories such as race and gender but did not define how these categories were assigned. Search dates: October 1 to November 30, 2022, and November 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.