This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(6):595-604

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

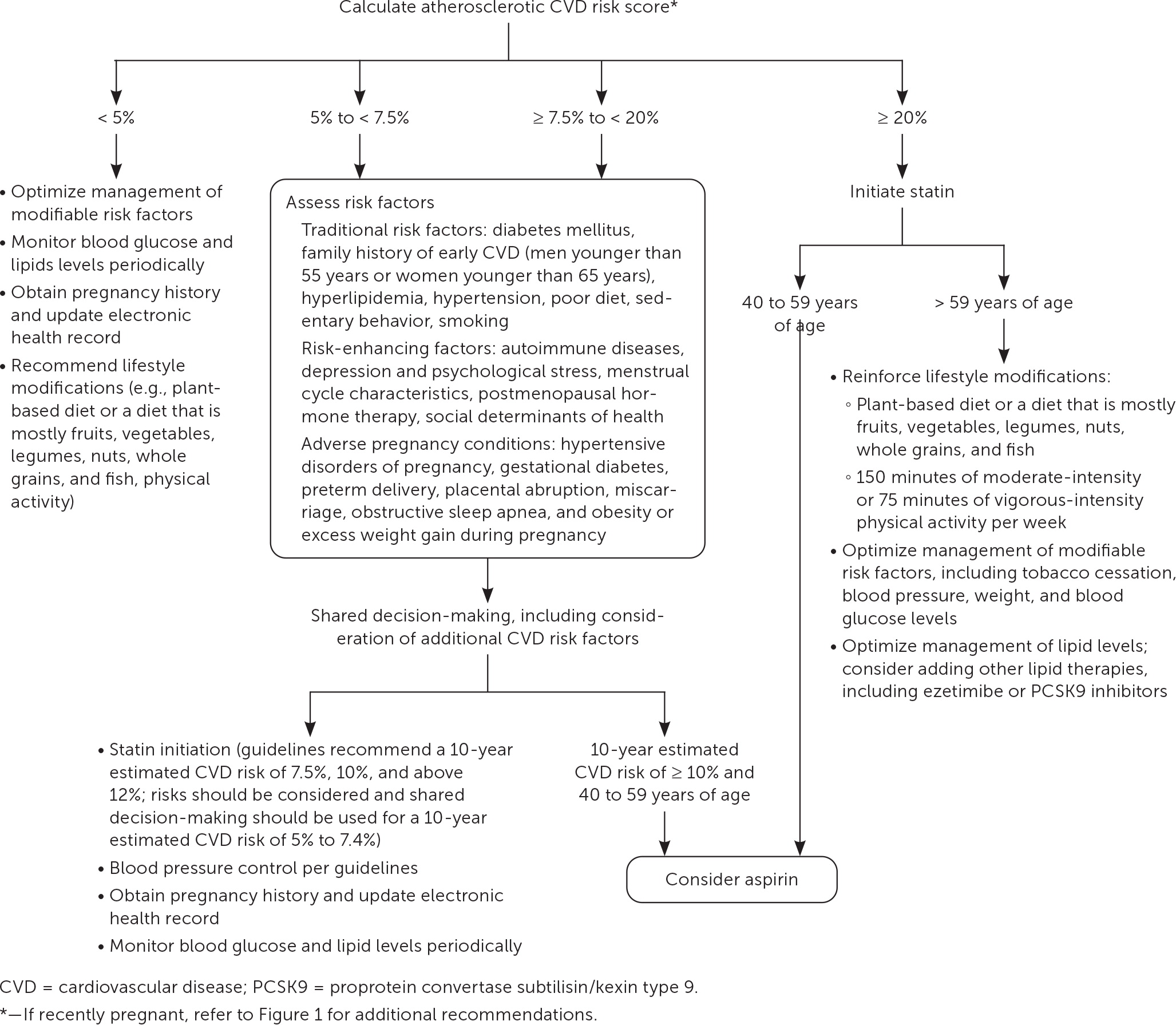

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most common cause of mortality in the United States. Women have unique risk factors for CVD, including pregnancy, hormones, autoimmune disorders, and psychological stress. Most risk calculators underestimate the risk of CVD in women; therefore, it is essential that physicians have a heightened awareness of risk-enhancing factors. A thorough history of adverse pregnancy conditions, hormonal factors, autoimmune diseases, and psychological stress, including adverse social determinants of health, should be documented in the electronic health record. A risk assessment using the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator should be routinely performed, and those with borderline (5% to less than 7.5%) and intermediate (7.5% to less than 20%) risk should undergo lifestyle modification counseling and shared decision-making regarding the initiation of a statin, aspirin, or antihypertensive therapy. Women with gestational diabetes mellitus should be screened at four to 12 weeks postpartum with a two-hour oral glucose tolerance test, and, if normal, the test should be repeated every one to three years. Women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be assessed within three months of delivery, and CVD risk assessment should occur annually thereafter. Because women with a history of adverse pregnancy conditions have higher rates of traditional CVD risk factors that emerge at younger ages, earlier and more frequent monitoring should be considered. Optimizing management of mood disorders, traditional CVD risk factors, and autoimmune diseases and considering the effects of social determinants of health are essential. Lifestyle modification counseling should include guidance to adhere to a plant-based diet that is mostly vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, and fish; 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise weekly; and tobacco cessation.

Although cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the most common cause of death in the United States, CVD mortality rates have decreased over the past 40 years.1 The greatest gains were in men and women older than 65 years. However, women younger than 55 years experienced the smallest decline in mortality and an increase in hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction from 2000 to 2009.2 Women are largely underrepresented in research studies, and data on prevention strategies are derived from studies in men, possibly explaining why the decline in the rate of CVD mortality in men is greater than that in women.1,3 Although terminology is not consistent and is used interchangeably, most studies refer to the term woman as sex assigned at birth and compared women with men.3 When counseling patients, physicians recognize traditional CVD risk factors but may be uncertain about how to account for the unique stages across a woman’s life span that can increase CVD risk, including factors related to pregnancy, hormones, autoimmune disorders, psychological stress, and social determinants of health. These risk factors are summarized in Table 1.4–23

| In a systematic review including more than 3 million women, a history of gestational diabetes mellitus doubled the risk of cardiovascular events in the first 10 years after pregnancy, with an NNH of 200. |

| Women who had preeclampsia during pregnancy have a higher risk of future hypertension (NNH = 6 over 11 years), ischemic heart disease (NNH = 333 over 12 years), and stroke (NNH = 666 over 10 years) than those who did not. |

| Compared with menopause onset at 55 years or older, cardiovascular events occur more often in those with earlier onset, with 2.6 events per 1,000 person-years for onset between 45 and 49 years of age, 3 events per 1,000 person-years for onset between 40 and 45 years of age, and 4 events per 1,000 person-years for onset before 40 years of age. [corrected] The median time from menopause to development of cardiovascular disease is 12 years. |

| In an 18-year longitudinal cohort study, women diagnosed with depression at enrollment had double the incidence of coronary heart disease after adjusting for traditional risk factors. |

| Risk-enhancing factor | Risk of CVD (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy-related | |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus4 | RR = 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5); risk is highest in the first 10 years after affected pregnancy |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 5 | |

| Preeclampsia | Heart disease: RR = 2.16 (1.86 to 2.52); if preeclampsia occurs at < 37 weeks’ gestation: RR = 7.71 (4.40 to 13.52) Stroke: RR = 1.81 (1.45 to 2.27) |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | RR = 3.7 (2.7 to 5.05) Postpregnancy hypertension: RR = 3.39 (0.82 to 13.92) |

| Miscarriage6 | OR = 1.45 (1.18 to 1.78); if recurrent miscarriage: OR = 1.99 (1.13 to 3.50) |

| Obesity/excessive weight gain7 | Heart disease: HR = 2.63 (1.41 to 4.01) compared with women who are healthy weight Stroke: HR = 1.89 (1.25 to 2.84) compared with women who are healthy weight |

| Obstructive sleep apnea8 | No data on CVD risk but increases adverse pregnancy conditions, reported as pooled aOR Gestational hypertension: aOR = 1.97 (1.51 to 2.56) Gestational diabetes: aOR = 1.55 (1.26 to 1.90) Preeclampsia: aOR = 2.35 (2.15 to 2.58) Preterm birth: aOR = 1.62 (1.29 to 2.0) |

| Placental abruption9 | OR = 1.8 (1.4 to 2.3) |

| Preterm births10 | RR = 1.56 (1.32 to 1.84); if preterm birth < 32 weeks’ gestation or patient has had more than two preterm deliveries: RR = 1.85 (1.51 to 2.28) |

| Hormone-related | |

| Menopause before 50 years of age 11 | Increases risk of first event before 60 years of age, but risk returns to baseline after 70 years of age |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome 12 | RR = 2.02 (1.47 to 2.76); does not clearly increase risk independently but is associated with greater risk due to overlapping risk factors |

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy 13,14 | Heart disease: Conflicting data regarding risks and benefits; not recommended for primary prevention of CVD Stroke: Increases risk in a dose-dependent manner, especially when prescribed > 10 years after menopause onset |

| Other | |

| All autoimmune diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, type 1 diabetes)15–17 | Risk increase depends on disease activity; higher risk of developing CVD before 65 years of age: HR = 1.97 (1.90 to 2.05) |

| Depression and psychological distress18–22 | Early-onset CVD: RR = 2.01 (1.19 to 4.82) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis17 | Increased CVD mortality rate: standardized mortality ratio = 1.50 (1.39 to 1.61) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus17,23 | Increased risk of myocardial infarction in women 35 to 44 years of age: risk ratio = 52.4 (21.6 to 98.5) |

What Sex-Specific and Risk-Enhancing Conditions Impact a Woman’s Future CVD Risk?

Pregnancy Conditions

A history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) doubles CVD risk in the first 10 years after pregnancy and increases lifelong risk, even in patients who never develop diabetes outside of pregnancy. Women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and other adverse pregnancy conditions, including preterm birth, recurrent miscarriage, placental abruption, sleep apnea, and excess weight, have a higher relative risk (RR) of CVD.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review that included more than 3 million women showed that those with a history of GDM have double the risk of CVD events in the first 10 years after pregnancy, with a number needed to harm (NNH) of 200 (9 per 1,000 vs. 4 per 1,000).24 Even those who do not develop diabetes outside of pregnancy have a 56% higher risk of CVD events.4 Women who develop nongestational diabetes have a higher CVD risk than men of the same age.25 Young women are less likely to receive recommended treatment for CVD risk reduction.25

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy include preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension. A systematic review and meta-analysis that included more than 3.4 million women found that those with gestational hypertension have a higher risk of hypertension and CVD later in life.5 Women with preeclampsia during pregnancy have a higher risk of hypertension (NNH = 6; 228 per 1,000 patients vs. 65 per 1,000 patients over 11 years), ischemic heart disease (NNH = 333; 5 per 1,000 patients vs. 2 per 1,000 patients over 12 years), and stroke (NNH = 666; 2 per 1,000 patients vs. 0.5 per 1,000 patients over 10 years) than women who do not. Women who develop preeclampsia before 37 weeks’ gestation have an even greater risk, with a nearly eightfold increase in ischemic heart disease and a fivefold increase in stroke compared with women who developed preeclampsia after 37 weeks’ gestation.

Other adverse pregnancy conditions can also increase CVD risk. A systematic review that included more than 5.8 million women found that preterm delivery was associated with a 1.4- to twofold increase in CVD events, death, and stroke. Future maternal risk was highest after preterm births earlier than 32 weeks’ gestation that were due to fetal growth restriction or preeclampsia.10 Systematic reviews have also demonstrated an increased CVD risk after miscarriage and placental abruption.6,9 Obstructive sleep apnea and obesity or excess weight gain during pregnancy can increase the risk of adverse pregnancy conditions and subsequent CVD.7,8,26–30

Menstrual Characteristics

Early-onset menopause increases the risk of a first CVD event before 60 years of age, and the risk increases with each year of onset occurring before 50 years of age. Although polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is associated with an elevated CVD risk, it is unclear whether this increase is due to PCOS or other patient factors.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Researchers studied the association between the age of menopause and occurrence of first nonfatal CVD event.11 Compared with menopause onset at 55 years or older, CVD events occur more often in those who have an earlier onset, with 2.6 events per 1,000 person-years for onset at 45 to 49 years of age, 3 events per 1,000 person-years for onset at 40 to 45 years of age, and 4 events per 1,000 person-years for onset before 40 years of age. [corrected] The median time from menopause to the development of CVD is 12 years.11 CVD event risk increases by 3% for each year that the onset of menopause occurs before 50 years of age (hazard ratio = 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.04; P < .0001).11 By 70 years of age, CVD event risk is not affected by age at menopause.11

Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy

Hormone therapy is not recommended to reduce CVD risk at any age. Although small studies suggest that hormone therapy in early menopause may reduce CVD risk, there are no high-quality studies demonstrating cardioprotective benefit. When hormone therapy is used for menopausal symptoms, transdermal estrogen with a dosage of less than 50 mcg per day appears to be safer than oral estrogen.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Postmenopausal hormone therapy has been controversial due to inconsistent findings among studies and generally low- or moderate-quality evidence based on observational data. Recommendations against postmenopausal hormone therapy for CVD prevention were reaffirmed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 2023 and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2022.13,31

Moderate-quality evidence based on observational studies found that in healthy postmenopausal women younger than 60 years and within 10 years of menopause onset, hormone therapy is associated with reduced CVD risk and no increased stroke risk.14 However, a more recent systematic review of the evidence by the USPSTF did not find any significant benefit overall for estrogen alone or estrogen combined with progesterone in the primary prevention of CVD.31 When used for menopausal symptoms, transdermal estrogen confers a lower risk of thrombotic complications or stroke compared with oral formulations, especially with a dosage of less than 50 mcg of estradiol per day.13

Autoimmune Disease

Although sex-specific data are limited, studies show an increased risk of CVD and CVD-related mortality in women with autoimmune diseases compared with those without. Those with the greatest disease severity and duration are at the highest risk.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Women with autoimmune diseases have a higher CVD risk and earlier onset.15 The CVD risk correlates with autoimmune disease activity.15 For example, CVD risk increases with the duration of rheumatoid arthritis flare-ups.16 CVD mortality is higher in people with autoimmune diseases, and those with rheumatoid arthritis have a 50% higher mortality rate than those without an autoimmune disease.17 Another study identified a 50-fold increase in the RR of myocardial infarction in women 35 to 44 years of age with lupus compared with women of the same age without an autoimmune disease.23

Depression and Psychological Stress

The presence of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, exposure to toxic stress in childhood, or adverse social and environmental conditions doubles or triples CVD risk and may be an important risk factor for early-onset CVD. Treating depression before the onset of CVD may reduce future risk.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Studies have long linked depression and psychological stressors to CVD.18 In an 18-year longitudinal cohort study of 860 women, those diagnosed with depression at enrollment had double the incidence of early-onset CVD (RR = 2.01; 95% CI, 1.19 to 4.82) after adjusting for traditional risk factors.19 Two studies demonstrated that a depression diagnosis at baseline increased the risk of CVD and nearly tripled the mortality risk (RR = 2.9; 95% CI, 1.2 to 7.1).20,21 A 2014 study of 235 patients who had depression, with or without CVD, evaluated whether treatment of depressive symptoms would reduce the occurrence of CVD. Those with depression and no CVD at baseline had a 48% lower risk of a major CVD event (P = .011; number needed to treat = 6.1).32

Most studies that evaluated CVD risk in patients with adverse childhood events demonstrated an increased risk of CVD in these patients, with stronger associations and earlier CVD onset in women than men.22,33 Factors related to social determinants of health, including environmental stressors and psychosocial factors, have been theorized to alter inflammation and immune function, leading to the development of atherosclerotic plaque and other CVD risk factors that contribute to CVD morbidity and mortality.34

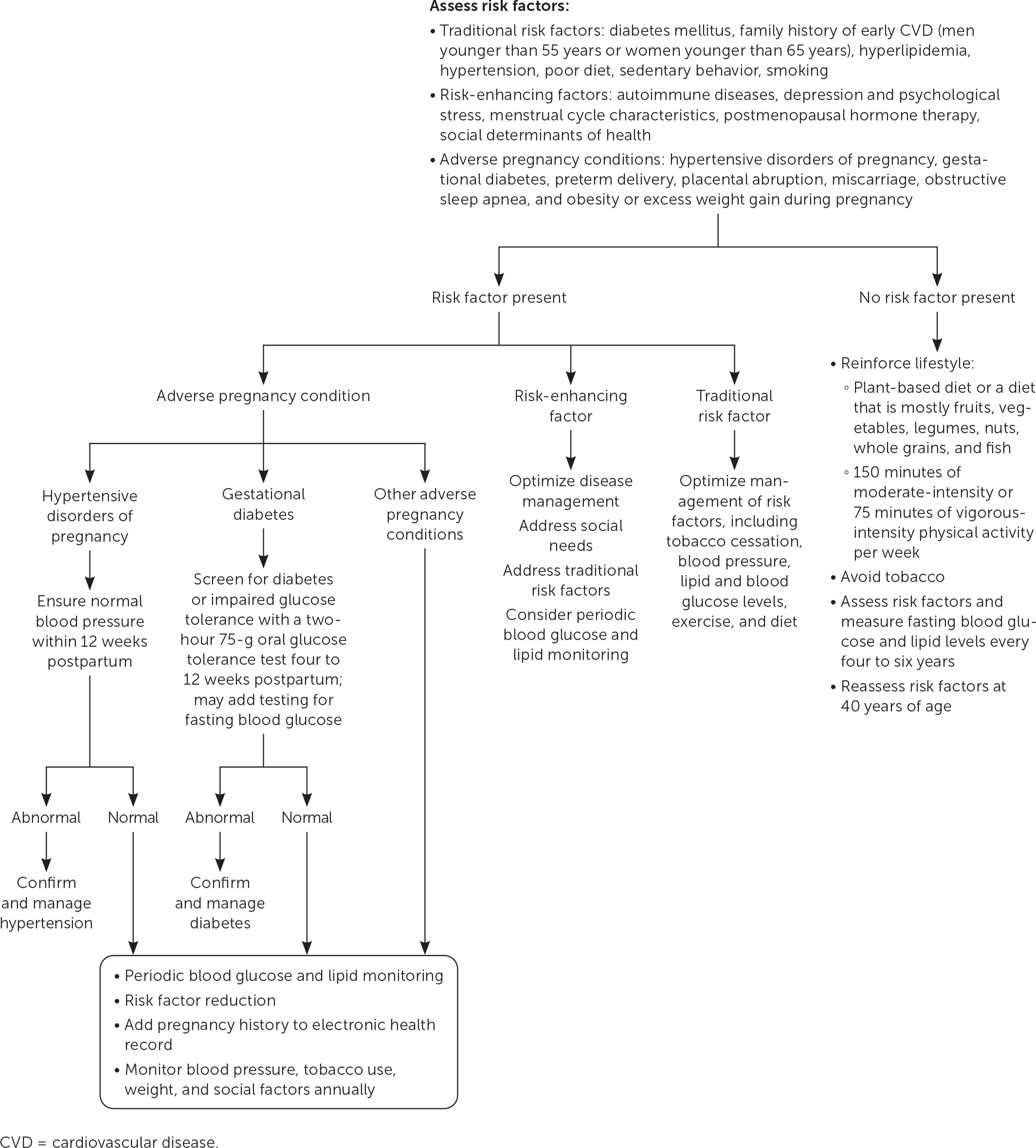

How Should Adverse Pregnancy Conditions Be Managed After Delivery?

Because women with a history of adverse pregnancy conditions have higher rates of traditional CVD risk factors that emerge at younger ages, earlier and more frequent monitoring should be considered. Based on expert opinion, women with GDM should be screened at four to 12 weeks postpartum with a two-hour oral glucose tolerance test, and, if normal, the test should be repeated every one to three years. Women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be assessed within three months of delivery, and a CVD risk assessment should be performed annually thereafter. Documentation of the pregnancy condition in the electronic health record is essential.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In a Dutch study following more than 2,800 patients, women with previous hypertensive disorders of pregnancy had increased rates of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes.35 From 35 to 40 years of age, 1 in 9 women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy will have clinically relevant hypertension compared with 1 in 38 women with normotensive pregnancies. Despite a lack of clinical evidence for monitoring CVD risk after adverse pregnancy conditions, ACOG recommends assessing lipid and fasting blood glucose levels, blood pressure measurements, body mass index, and tobacco use, and providing counseling on lifestyle interventions within three months postpartum, and then annually, to lower CVD risk in women with adverse pregnancy conditions and CVD risk factors.36,37 Women with GDM should complete a two-hour oral glucose tolerance test four to 12 weeks postpartum and then every one to three years thereafter.38 Because of the increased risk of adverse pregnancy conditions in subsequent pregnancies, ACOG recommends counseling women on the increased future risk within the first three months after an adverse pregnancy condition.36 ACOG recommends documenting adverse pregnancy conditions and communicating the risks to the primary care team.39

What Is Recommended for Primary Prevention of CVD in Women With Sex-Specific or Risk-Enhancing Factors?

Recommendations for the primary prevention of CVD in women with an increased risk are limited. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines suggest that physicians perform a 10-year CVD risk assessment and use shared decision-making regarding the initiation of a statin or antihypertensive medication in women with conditions that increase the risk of CVD, even in those younger than 40 years. The USPSTF and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense (VA/DoD) do not discuss adjusting screening for other risk factors and recommend risk screening only for women 40 years and older. The role of a coronary artery calcium score to further stratify CVD risk is uncertain. Primary prevention recommendations are summarized in Table 2. 40–42

| Organization | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association40 | Severe hypercholesterolemia (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level ≥ 190 mg per dL [4.92 mmol per L]) Diabetes mellitus in adults 40 to 75 years of age Adults 40 to 75 years of age at high risk (≥ 20%) and some adults at intermediate risk (7.5% to < 20%) or borderline risk (5% to < 7.5%) based on the presence of risk enhancers (including sex-specific risk factors), elevated coronary artery calcium score, if measured, and physician-patient risk discussion |

| U.S. Preventive Services Task Force41 | Adults 40 to 75 years of age with one or more CVD risk factor (e.g., dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and atherosclerotic CVD risk > 10% Consider selectively offering statin therapy to adults 40 to 75 years of age with one or more CVD risk factor and atherosclerotic CVD risk of 7.5% to < 10% |

| Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense42 | CVD risk > 12%, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level ≥ 190 mg per dL, or diabetes Consider initiation or shared decision-making if atherosclerotic CVD risk is 6% to 12% |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines on the primary prevention of CVD recommend statin therapy and lifestyle interventions, including diet, exercise, and weight loss, in three groups of patients.40 The guideline also recommends performing a quantitative 10-year CVD risk assessment with a validated risk prediction tool, such as the Atherosclerotic CVD Risk Calculator (available at https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3398/ascvd-atherosclerotic-cardiovascular-disease-2013-risk-calculator-aha-acc). The Atherosclerotic CVD Risk Calculator is validated only in patients 40 to 75 years of age. Risk calculators can underestimate the risk of CVD in women; therefore, it is essential that physicians have a heightened awareness of risk-enhancing factors. Primary prevention of CVD by age is summarized in Figure 136–41,43 and Figure 2.40,41,43,44

Although statins should be offered to patients who are at high risk (10-year estimated CVD risk score of 20% or more), statins can be considered in patients with an intermediate risk (10-year estimated CVD risk score of 7.5% to less than 20%). A 10-year estimated CVD risk score of 5% to less than 7.5% is considered borderline risk. The decision to begin a statin or antihypertensive should consider the presence and severity of traditional CVD risk factors, other sex-specific and risk-enhancing conditions, lifestyle choices, social determinants of health, and risks and benefits of statin therapy. Measuring fasting blood glucose and lipid levels every four to six years between 20 and 39 years of age is recommended despite a lack of high-quality evidence.43

The USPSTF recommends statin therapy for those 40 to 75 years of age who have one or more CVD risk factor (e.g., dyslipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and an estimated 10-year CVD risk score of 10% or greater, whereas the VA/DoD recommends initiation when the risk exceeds 12% and shared decision-making when a patient has a 6% to 12% risk and other risk factors.41,42 Some guidelines recommend considering coronary artery calcium scores in select patients; however, the USPSTF notes that the evidence is inadequate to assess whether coronary artery calcium, arterial brachial index, or high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurements improve risk assessment compared with existing risk assessment calculators.40,43,45

The USPSTF and VA/DoD guidelines do not include sex-specific recommendations for the initiation of a statin. When discussing the risks and benefits of statin use with premenopausal women, the discussion should include the risks of statin use in pregnancy. Nonstatin therapies can be considered for pregnant women who require cholesterol lowering or women who experience myalgias while on statins, including ezetimibe and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors; however, studies that showed benefit were largely performed in men and did not assess patient-oriented outcomes.43,46

What Is the Role of Aspirin for Primary Prevention of CVD in Women?

For most women, the risks of aspirin outweigh the benefit, especially in women 60 years and older. Some women 40 to 59 years of age with an estimated 10-year CVD risk of 10% or greater may benefit from low-dose aspirin for primary prevention.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Although early studies suggested that aspirin could reduce CVD events, recent trials have found that the benefit of CVD prevention is outweighed by the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. A 2019 systematic review reported a number needed to treat of 241 (95% CI, 170 to 345) to prevent one CVD event vs. an NNH of 212 (95% CI, 161 to 294) for major bleeding, confirming that the harms outweigh any benefit.47 The 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines on the primary prevention of CVD state that most healthy people do not need to take aspirin; however, there were no sex-specific recommendations.40 One review recommends consideration of low-dose aspirin for select women at high risk of CVD.48 In 2022, the USPSTF provided updated recommendations on aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD based on microsimulation modeling of hypothetical cohorts of men and women 40 to 79 years of age with a 10-year CVD risk of up to 20%. The USPSTF found that men and women 40 to 59 years of age who have a 10-year CVD risk of 10% or greater are most likely to have a lifetime benefit from aspirin and recommended against initiating low-dose aspirin for primary prevention in adults 60 years and older.44

What Lifestyle Choices Help to Reduce CVD Risk in Women?

Diet, physical activity, and tobacco cessation are all important factors for CVD risk reduction. A diet emphasizing vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, fish, and whole grains, with at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or an equivalent combination, can reduce CVD risk and may reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes. Cigarette smoking increases the rate of CVD in women more than in men, and interventions that combine behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy should be used to promote cessation.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A retrospective analysis of more than 63,000 women from the Women’s Health Initiative over 12.9 years showed that women who reported consuming higher-quality diets that emphasized fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and plants or plant-based proteins experienced 20% less CVD mortality than women who did not, even when correcting for body mass index.49 Consuming at least one sugar-sweetened beverage per day increases the risk of CVD, even when controlled for confounding variables such as quality of diet and obesity.50 The ACC/AHA guidelines emphasize eating vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, and fish.40

Lifestyle modification programs that include physical activity have a moderate impact on CVD risk factors.51 The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise per week, or an equivalent combination, to reduce CVD risk.52 During pregnancy, this amount of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week may lower the risk of adverse pregnancy conditions.52

Smoking cessation is important for women. A meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies showed that women who smoke one pack per day have higher rates of CVD than men with similar smoking habits and men and women who have never smoked.53 The USPSTF recommends providing behavioral interventions and pharmacotherapy to adults to aid in smoking cessation.54 Pregnant women who smoke should be offered behavioral interventions because the benefits and harms of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy are not understood.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Hayes55 and Bedinghaus, et al.56

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms cardiovascular disease prevention and women. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, the Cochrane database, Trip, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, American Heart Association, MDCalc Medical Calculator, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. The terms gender and sex were often used interchangeably and not well defined in most studies and reviews. Whenever possible, studies that used race as patient categories but did not define how they were assigned were not included in our final review. Search dates: October 2022, and January, March, June, and September 2023.