Am Fam Physician. 2024;109(1):71-78

Related Letter to the Editor: Concurrent Cocaine Use in Individuals With Alcohol Use Disorder

Related Letter to the Editor: Alcohol Use Disorder and Expectation-Based Medicines

Related Implementing AHRQ Effective Health Care Reviews: Pharmacotherapy for Adults With Alcohol Use Disorder

Related article: Substance Misuse in Adults: A Primary Care Approach

Related AFP Community Blog: Why Medications for AUD Should Be as Popular as GLP-1 Agonists for Obesity

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Excessive alcohol use is a leading cause of preventable death in the United States, with alcohol-related deaths increasing during the pandemic. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends that physicians offer pharmacotherapy with behavioral interventions for patients diagnosed with alcohol use disorder. Several medications are available to help patients reduce drinking and maintain abstinence; however, in 2019, only 7.3% of Americans with alcohol use disorder received any treatment, and only 1.6% were prescribed medications to treat the disorder. Strong evidence shows that naltrexone and gabapentin reduce heavy-drinking days and that acamprosate prevents return-to-use in patients who are currently abstinent; moderate evidence supports the use of topiramate in decreasing heavy-drinking days. Disulfiram has been commonly prescribed, but little evidence supports its effectiveness outside of supervised settings. Other medications, including varenicline and baclofen, may be beneficial in reducing heavy alcohol use. Antidepressants do not decrease alcohol use in patients who do not have mood disorders, but they may help patients who meet criteria for depression to decrease their alcohol intake. Systematic policies are needed to expand the use of medications when treating alcohol use disorder in inpatient and outpatient populations.

Excessive alcohol use is a leading cause of preventable death in the United States, contributing to an estimated 1 in 5 deaths among adults 20 to 49 years of age between 2015 and 2019.1 Alcohol-related deaths in the United States have been increasing steadily for the past two decades at a rate of 2.2% per year.2 This trend accelerated significantly after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic; preliminary data show that where alcohol was listed as a proximate cause on the death certificate, a 25.9% increase in deaths occurred in the first 12 months after March 2020 (79,000 to 95,000 deaths) compared with the previous year.2 Excessive alcohol consumption is also a major risk factor for many common chronic conditions, including high blood pressure, sleep apnea, and liver disease.3 The health effects of alcohol are most closely related to the total amount of alcohol consumed, as well as the number of heavy-drinking days, with a linear increase in alcohol-related mortality for every heavy-drinking day.4 A heavy-drinking day is defined as three or more standard drinks in a day for a woman and four or more in a day for a man.

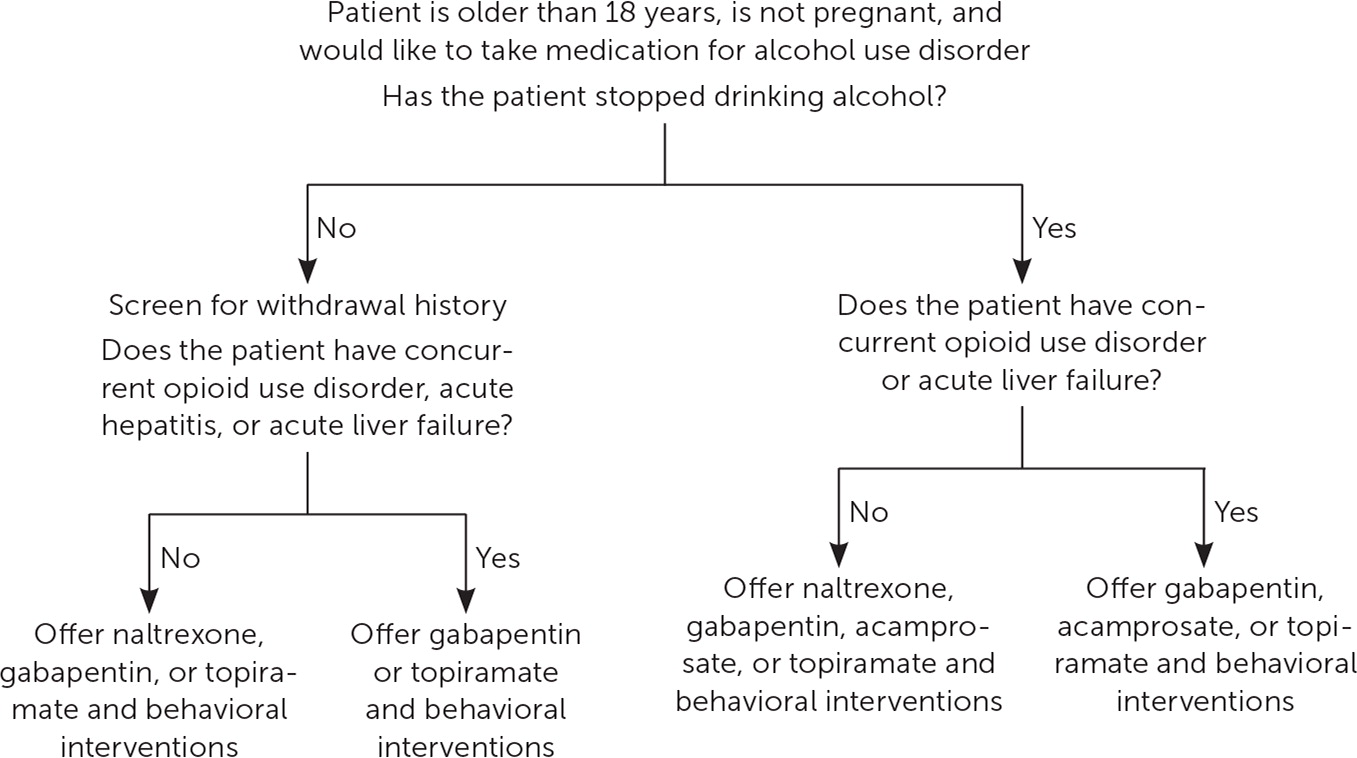

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recommends that physicians offer pharmacotherapy with behavioral interventions for patients diagnosed with alcohol use disorder (AUD).6 However, in 2019 only 7.3% of Americans with AUD received any treatment, and only 1.6% received medication therapy.7 Medications should be offered routinely to patients with AUD, and systematic policies are needed to expand their use in inpatient and outpatient populations. Recommendations for screening and management of alcohol use in the outpatient setting are listed in Figure 1; recommended medications for the treatment of AUD in the outpatient setting are discussed in Figure 2.

Medications to Treat AUD

Previous reviews found moderate to strong evidence for the use of specific medications to treat AUD; all support offering these medications to patients diagnosed with AUD if the patient wants to moderate or cease their alcohol use.8 A previous FPM article provides a review of screening for AUD.9 Oral naltrexone (Revia) and injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol), acamprosate, and disulfiram are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AUD; other medications have been studied for off-label use. A 2023 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality review found moderate evidence to support the use of naltrexone and acamprosate and insufficient evidence to support the use of disulfiram.10 The same review also found moderate evidence for the use of topiramate.10 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration released a 2015 guideline with similar recommendations, except that the guideline endorses the use of disulfiram in supervised settings.6 The American Psychiatric Association's 2018 guideline on pharmacology for AUD endorses using naltrexone and acamprosate as first-line treatments and gabapentin, topiramate, and disulfiram as second-line treatments.11

More recently, several trials have demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of gabapentin in reducing heavy-drinking days, particularly for those who self-reported more alcohol withdrawal symptoms.12 Patients with AUD are at risk of alcohol withdrawal and may require medical management for withdrawal before treatment can be initiated, particularly if they have a history of severe withdrawal symptoms.13 There is no strong evidence regarding the duration of treatment, but typically medications are continued for at least six to 12 months after a patient has stopped drinking. In those with ongoing cravings for alcohol who are not having medication-related adverse effects, treatment can be extended. Table 1 summarizes the medications used to treat AUD.10,12,14

| Medication | Target population goals | Dosing regimen | Most common adverse effects | Contraindications | Number needed to treat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naltrexone (oral; Revia)* | Reduce heavy-drinking days or remain abstinent | 50 mg orally per day (can start with 25 mg or increase to 100 mg as tolerated) | Nausea, headache, insomnia | Concurrent opioid use Use caution in decompensated cirrhosis | 12 to decrease heavy-drinking days10 |

| Naltrexone (intramuscular; Vivitrol)* | Reduce heavy-drinking days or remain abstinent | 380 mg intramuscularly per month | Nausea, headache, insomnia (less common than with oral naltrexone); injection-site reaction | Concurrent opioid use Use caution in acute liver failure | Likely similar to or better than oral naltrexone but too few studies to definitively calculate |

| Gabapentin | Reduce heavy-drinking days | 300 mg on day 1; add 300 mg per day (i.e., day 2: 600 mg; day 3: 900 mg), titrating to final dosing regimen Titrate up to maximum of 3,600 mg per day Typical dosage: 600 mg three times daily | Somnolence, peripheral edema, confusion, falls | Use caution in renal impairment but can adjust dosage in all stages of kidney disease | 5 to decrease heavy-drinking days12 |

| Acamprosate | Remain abstinent | 666 mg orally three times per day (333 mg three times per day if CrCl is 30 to 50 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 [0.50 to 0.83 mL per second per m2]) | Nausea, diarrhea | CrCl < 30 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 | 12 to prevent return-to-drinking10 |

| Topiramate (immediate release) | Reduce heavy-drinking days | 25 mg per day; increase by 25 to 50 mg every week to maximum dosage of 300 mg per day | Gastrointestinal upset, parasthesias, cognitive impairment, rash, weight loss, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis | None | 5 for zero heavy-drinking days10 |

| Baclofen | Reduce risk of relapse for those who have stopped drinking; consider for patients with cirrhosis | Variable dosing ranging from 15 to 80 mg per day (trials range from 30 to 300 mg per day); maximum dosage is limited by adverse effects | Sedation or overdose risk at high dosages, dizziness, headache, nausea | Use caution in renal impairment or in combination with sedating medications | Too few studies to calculate |

| Varenicline (Chantix) | Reduce heavy-drinking days; patients who want to quit using tobacco | 0.5 mg per day for 3 days, 0.5 mg twice per day for 4 days, then 1 mg twice per day thereafter | Nausea, vomiting, abnormal dreams, worsening psychiatric disease (e.g., worsening depression, suicidal ideation) | None | Too few studies to calculate |

| Disulfiram | Remain abstinent when supervised for adherence | 250 mg orally once per day; maximum dosage of 500 mg per day | Bitter or metallic taste, headache, vomiting, psychosis, liver failure (rare), peripheral neuropathy | Currently actively drinking, use of metronidazole (Flagyl) or other alcohol-containing agents (e.g., cough syrups), psychosis, severe myocardial disease, esophageal varices, current pregnancy | Not evaluated |

Agents With Strong, Consistent Evidence

NALTREXONE

Naltrexone has strong evidence for effectiveness in the treatment of AUD and may be used in patients who are actively drinking.10 Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, reduces alcohol consumption by decreasing cravings and blocking the pleasurable effects of alcohol. Naltrexone is available in oral and injectable, intramuscular long-acting formulations. It may be combined with other medications (e.g., acamprosate, topiramate, gabapentin) that primarily target post-acute withdrawal symptoms, which are a constellation of symptoms that include anxiety, irritability, and insomnia that may last six months or longer after cessation of alcohol use.15

A 2010 Cochrane review that included 50 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 7,793 patients found that oral naltrexone prevented patients who were drinking heavily from returning to any heavy drinking during the treatment period (number needed to treat [NNT] = 9) and slightly decreased daily drinking (NNT = 25).16 The number of heavy-drinking days and the amount of alcohol consumed also decreased.16 Injectable naltrexone can be given every 28 days by a health care professional. With the injectable, monthly formulation, patients are more likely to adhere to therapy for the duration of the month, and, because of more predictable metabolism, patients are less likely to experience adverse effects.17 Few studies have directly compared oral vs. injectable naltrexone; however, some low-quality evidence supports intramuscular naltrexone as more effective.18 In 2019, a retrospective chart review of 32 patients found time-to-return to use of alcohol was 150 days for intramuscular naltrexone vs. 50 days for oral naltrexone.18

Oral naltrexone is generally well tolerated. The most common adverse effects are nausea, headache, and insomnia, which generally improve after taking the medication consistently. Adverse effects with intramuscular naltrexone are the same as oral naltrexone but are less common because of its more predictable metabolism and lower overall dose; adverse effects also include injection-site pain. Naltrexone can precipitate severe opioid withdrawal, so opioids should not be used for at least seven days before starting naltrexone. Acute pain management may be challenging for patients taking naltrexone. Those using intramuscular na ltrexone should carry a medical alert card and be counseled on this issue, and pain specialists should be consulted in the case of significant injury or planned procedures.

GABAPENTIN

Some anticonvulsants appear to be useful in treating post-acute withdrawal symptoms, preventing severe withdrawal in the acute period, and reducing heavy-drinking days; of the anticonvulsants, gabapentin has the strongest evidence for support.19 A meta-analysis evaluating seven RCTs of gabapentin vs. placebo or active comparator found a moderate effect size (g = −0.64) of gabapentin for reduced percentage of heavy-drinking days but no significant effect on the percentage of days abstinent, drinks per day, or complete abstinence.19 Dosages ranged from 300 to 3,600 mg per day for up to 26 weeks of treatment.19 A double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT with 90 patients found that those treated with gabapentin, 1,200 mg per day for 16 weeks, had higher rates of no heavy-drinking days (NNT = 5).12 A subgroup analysis found that gabapentin had increased effectiveness in patients with more self-reported withdrawal symptoms (based on the Modified Alcohol Withdrawal Symptoms Checklist) at baseline.12 Taking gabapentin is safe for patients who are actively drinking.12,19 Some literature raises concerns about misuse of gabapentin, but these concerns often involve patients taking gabapentin to decrease anxiety and withdrawal symptoms, which are key clinical targets in AUD.20,21 Weighing the risks of untreated AUD vs. a potential development of gabapentin use disorder is necessary.

ACAMPROSATE

Acamprosate is effective at maintaining abstinence in patients who are not currently drinking alcohol.22 Acamprosate interacts with the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor, although its exact mechanism is unclear.23 Its use is safe in patients who have impaired hepatic function but should be avoided in patients with stage 4 or 5 renal dysfunction. A 2010 Cochrane review of 24 trials involving 6,915 patients concluded that acamprosate reduced return-to- drinking compared with placebo (NNT = 9).24 A more recent systematic review and network meta-analysis of 35 acamprosate studies found that patients taking acamprosate were 33% more likely to remain abstinent (rate ratio [RR] = 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.54) and that heavy-drinking days vs. placebo had a RR of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.70 to 0.86).25 However, acamprosate must be taken three times daily to be effective, potentially limiting its utility, especially for patients with severe AUD.

TOPIRAMATE

There is moderate evidence that topiramate decreases the number of drinking days, heavy-drinking days, and drinks per day based on two RCTs with a total of 521 patients.10,26–28 However, an RCT of 106 patients did not show a difference in alcohol consumption between topiramate therapy and placebo.29 This study may have been underpowered and had an approximately 50% dropout rate.29 In a meta-analysis of topiramate for AUD that included seven trials, the authors found moderate effect sizes for topiramate on abstinence and heavy drinking.30 Topiramate's effectiveness may be limited by its adverse-effect profile, which includes paresthesias and cognitive impairment.

Agents With Less Consistent Evidence

BACLOFEN

A 2023 Cochrane review of 17 RCTs concluded that baclofen may be useful for reducing the risk of return to any drinking for patients who have stopped drinking (RR = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.99; NNT = 10); it may also increase the absolute percentage of abstinent days by 9% (95% CI, 3.3% to 14.8%).31 However, baclofen did not have a statistically significant effect on cravings compared with placebo.31 Studies have suggested that baclofen may be an effective option for patients with cirrhosis, and its renal clearance makes it an appealing option for this patient population.32–34 Serious safety concerns have been raised regarding the risk of sedation and overdose, particularly at high doses.34

VARENICLINE

Varenicline (Chantix) may be beneficial for AUD, particularly in patients who are drinking heavily and who concurrently smoke tobacco.35 An RCT of 200 adults found that the percentage of heavy-drinking days was significantly lower (38% vs. 48%; P = .03; NNT = 10) in the varenicline arm through 13 weeks of treatment.36 A meta-analysis of 22 RCTs representing 1,421 participants found that varenicline significantly improved abstinence days (standardized mean difference = 4.2 days; 95% CI, 0.21 to 8.19), reduced drinks per day slightly (standardized mean difference = −0.23 drinks; 95% CI, −0.43 to −0.04), and reduced alcohol cravings.37

Agents With Insufficient Data

DISULFIRAM

Despite FDA approval for this indication, disulfiram has limited evidence to support its effectiveness in nonsupervised settings. It does not reduce the craving for alcohol, but it causes unpleasant symptoms when alcohol is ingested because it inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase and alcohol metabolism. Adherence is a major limitation, and most evidence for the effectiveness of disulfiram comes from studies in which medication intake was supervised. One RCT assigned 243 patients to take naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram under supervision for 12 weeks and found that patients taking disulfiram had fewer heavy-drinking days, lower weekly consumption, and a longer period of abstinence compared with the other drugs.38 However, a 2020 systematic review and several other studies that looked at unsupervised populations found no significant difference in abstinence rates between disulfiram and placebo.39–41 Use of disulfiram is dangerous in patients who are actively drinking because it can cause severe vomiting; it should not be started until at least 24 hours after a patient's last drink.

Special Populations

PATIENTS WITH LIVER DISEASE

Both oral and intramuscular formulations of naltrexone are metabolized by the liver, and hepatotoxicity is possible; however, a case of acute liver failure definitively attributable to naltrexone has never been recorded, and naltrexone has been found to be safe in patients with compensated cirrhosis.42 Importantly, naltrexone prescription was associated with decreased likelihood of alcoholic liver disease in a nonrandomized cohort of 9,635 patients with diagnoses of AUD and decompensated cirrhosis, even when medication was initiated after the diagnosis of cirrhosis (odds ratio = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.95).43 The same improvements in outcomes were found with gabapentin but not with acamprosate.43 Therefore, although naltrexone is sometimes not offered to patients with hepatic dysfunction for fear that function may worsen, there is little evidence that its use is dangerous in these populations. Growing evidence supports that liver dysfunction is a compelling reason to initiate naltrexone.

ADOLESCENTS

Clinical trials have shown short-term effectiveness but high rates of return-to-use for several psychosocial interventions for adolescents with substance use disorders.44 Given developmental differences, adolescents may respond differently from adults to the same medications.45 Controlled trials examining the short-term effectiveness and tolerability of naltrexone and disulfiram in adolescents, as well as small pilot studies of ondansetron and topiramate, have been conducted.44,46–48 Collectively, these trials have shown that these medications are likely safe and may help reduce drinking in adolescents.44,46–48 However, the studies are too small to make a definitive recommendation, and more evidence is needed.44,46–48

PREGNANT PATIENTS

Despite the known teratogenic effects of alcohol use in pregnant patients, there are few studies on medications for AUD treatment during pregnancy; therefore, little evidence is available to guide the use of pharmacologic interventions for these patients.49 No published studies on the safety of naltrexone for AUD in pregnancy are available; however, some evidence from an observational study shows that it can be continued safely in pregnancy for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD).50 Gabapentin is associated with some adverse birth outcomes, although whether its role is causative is unclear.51 Disulfiram is not recommended because it can cause a severe reaction and put the pregnancy at risk.52 First-line treatment for AUD during pregnancy is behavioral intervention. In severe AUD and where behavioral interventions have failed, physicians should use shared decision-making with their patients regarding the risks of ongoing drinking compared with medication use in pregnancy and consider specialist consultation.53

PATIENTS WITH CO-OCCURRING OUD

Naltrexone has FDA approval for the treatment of AUD and OUD; however, only the intramuscular formulation is approved for OUD.54 If patients choose methadone or buprenorphine for OUD treatment, or if they are continuing to use opioids, then naltrexone cannot be initiated for AUD treatment because it blocks the opioid receptor. Although naltrexone may be an appropriate option for a patient with co-occurring OUD and AUD, it is important to note that buprenorphine and methadone have improved retention in treatment and reduce overdose risk, whereas naltrexone does not.55 Therefore, for most patients with concurrent OUD and AUD, methadone and buprenorphine are preferred, especially during the initial stages of treatment.56 In patients taking opioid agonists who are actively drinking alcohol, gabapentin, topiramate, and acamprosate should be considered.57

PATIENTS WITH CONCURRENT DEPRESSION

Several trials of patients with AUD who meet criteria for depression have shown effectiveness with antidepressants, including sertraline, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine.58,59 A Cochrane review of antidepressant use in patients with AUD and co-occurring depression found low-quality evidence that antidepressant use improves abstinence and reduces the number of drinking days.60 In patients with AUD who otherwise meet criteria for depression, antidepressants should be considered during early treatment, including in patients who are actively drinking, although there is not strong evidence that they should be used in patients with AUD who do not have a mood disorder.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Winslow, et al.61; Williams62; and Enoch and Goldman.63

Data Sources: A PubMed search was conducted in Clinical Queries using the terms alcohol use disorder, treatment, and medications. The search included randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, clinical trials, and reviews. The Cochrane database, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, the American Society of Addiction Medicine Clinical Guidelines, National Guideline Clearinghouse database, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. UpToDate was queried for review of medication adverse effects. Search dates: February 6, 13, and 28; March 15; April 5; and December 12, 2023.