Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(6):618-625

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

In the United States, pneumonia is the most common cause of hospitalization in children. Even in hospitalized children, community-acquired pneumonia is most likely of viral etiology, with respiratory syncytial virus being the most common pathogen, especially in children younger than two years. Typical presenting signs and symptoms include tachypnea, cough, fever, and anorexia. Findings most strongly associated with an infiltrate on chest radiography in children with clinically suspected pneumonia are grunting, history of fever, retractions, crackles, tachypnea, and the overall clinical impression. Chest radiography should be ordered if the diagnosis is uncertain, if patients have hypoxemia or significant respiratory distress, or if patients fail to show clinical improvement within 48 to 72 hours after initiation of antibiotic therapy. Outpatient management of community-acquired pneumonia is appropriate in patients without respiratory distress who can tolerate oral antibiotics. Amoxicillin is the first-line antibiotic with coverage for Streptococcus pneumoniae for school-aged children, and treatment should not exceed seven days. Patients requiring hospitalization and empiric parenteral therapy should be transitioned to oral antibiotics once they are clinically improving and able to tolerate oral intake. Childhood and maternal immunizations against S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, Bordetella pertussis, and influenza virus are the key to prevention.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a lung infection contracted outside of the hospital. Lower respiratory tract infection includes pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, or any combination of the three. In the United States, pneumonia is the most common cause of hospitalization in children.1

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not use broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ceftriaxone for children hospitalized with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia; use narrow-spectrum antibiotics such as penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin. | Society of Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, Academic Pediatric Association |

| Do not prescribe intravenous antibiotics for predetermined durations for patients hospitalized with infections such as pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis, and complicated pneumonia; consider early transition to oral antibiotics. | Society of Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, Academic Pediatric Association |

| Do not routinely use airway clearance therapy in conditions such as asthma, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia. | American Academy of Pediatrics—Section on Pediatric Pulmonology and Sleep Medicine |

Etiology

In a U.S. population of 2,638 patients younger than 18 years hospitalized with CAP, a viral pathogen was more likely than a bacterial pathogen (66% compared with 8%, respectively; 7% of patients had both viral and bacterial pathogens; no pathogen was identified in 19%).2

Respiratory syncytial virus is the most common pathogen overall, particularly in children younger than two years.2

Other common respiratory viruses include influenza virus, coronavirus (including SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19), human rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, and adenovirus.2

Due to routine childhood vaccinations, the prevalence of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae has decreased significantly. In the United States, the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine resulted in a reduction in hospitalizations for pneumococcal pneumonia from 53.6 to 23.3 per 100,000 admissions from 2006 to 2014.3

Table 1 shows the specific etiology in hospitalized children with pneumonia based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Etiology of Pneumonia in the Community study, a multicenter, population-based, prospective study conducted from 2010 to 2012.2

| Pathogen | Younger than 2 years | 2 to 4 years | 5 to 9 years | 10 to 17 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral | ||||

| Adenovirus | 18% | 9% | 4% | 2% |

| Coronaviruses | 6% | 6% | 3% | 4% |

| Human metapneumovirus | 14% | 17% | 10% | 4% |

| Human rhinovirus | 29% | 25% | 30% | 19% |

| Influenza A/B | 6% | 5% | 9% | 11% |

| Parainfluenza virus 1 to 3 | 7% | 8% | 6% | 4% |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 42% | 29% | 8% | 7% |

| Bacterial | ||||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 2% | 5% | 16% | 23% |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 3% | 4% | 4% | 3% |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 1% | 1% | < 1% | < 1% |

Diagnosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Typical presenting signs and symptoms include tachypnea, cough, fever, anorexia, dyspnea, retractions, and lethargy.2,4,5

In a series of 570 children one to 17 years of age with clinically suspected pneumonia, findings most strongly associated with an infiltrate on chest radiography were grunting (odds ratio [OR] = 7.3), history of fever (OR = 3.1), retractions (OR = 2.8), and crackles (OR = 2.0).6 Other findings associated with infiltrate included measured fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, and decreased breath sounds. Although grunting and retractions are uncommon, when present they have a high positive predictive value for pneumonia.6

Based on a systematic review of three studies, the overall clinical impression is moderately accurate for diagnosing CAP in children (positive likelihood ratio = 2.7; negative likelihood ratio = 0.63).7

Wheezing, retractions, and respiratory rate are the examination findings with the highest interrater reliability in children with CAP.8

CLINICAL PREDICTION RULES

Clinical prediction rules have been studied but have not been prospectively validated, particularly in primary care settings.6,9,10

The Bilkis Simpler Prediction Model has high sensitivity (93.8%) for the diagnosis of pneumonia in children presenting with any combination of fever, localized rales, decreased breath sounds, and tachypnea.9 A similar model also had excellent sensitivity (93% to 98%) but poor specificity (6% to 19%), making it unhelpful in clinical practice.6

The Pediatric Acute Febrile Respiratory Illness rule assigns points for duration of fever, chills, absence of nasal symptoms, tachypnea, and abnormal chest examination. Once prospectively validated in a new population, it may help clinicians to decide which children should have chest radiography.10

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

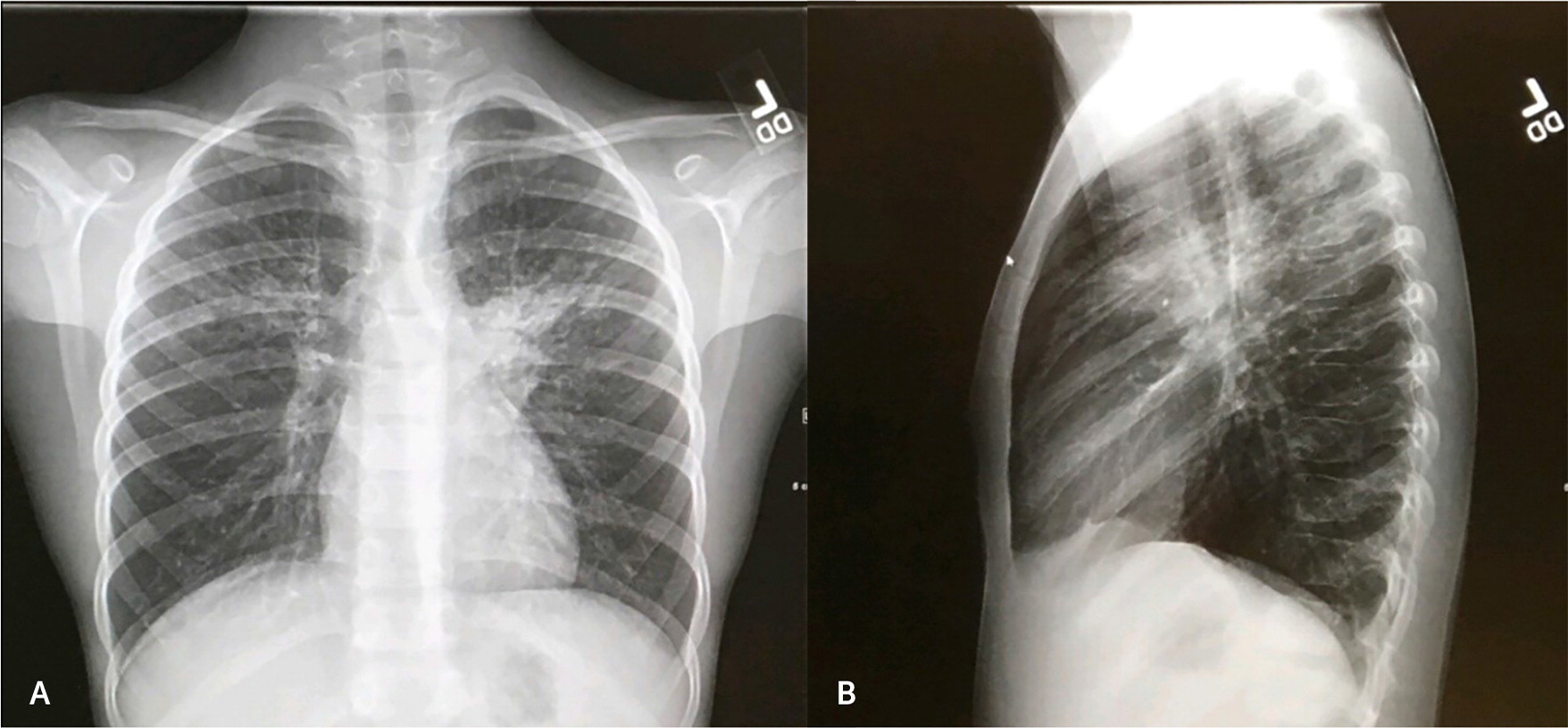

Chest radiography is not necessary to confirm suspected pneumonia in children in the outpatient setting. It should be obtained for patients with hypoxemia (oxygen saturation less than 90%) or significant respiratory distress or for those without clinical improvement within 48 to 72 hours after initiation of antibiotic therapy.11 Figure 1 shows a chest radiograph demonstrating a left upper-lobe opacity consistent with pneumonia.

Chest ultrasonography is more often used to evaluate local complications such as parapneumonic effusion or empyema, but it may also detect lung consolidation and save time and cost.12,13 Novice and expert physician-sonologists have achieved a reduction of chest radiography use in emergency department settings without missed cases of pneumonia or an increase in adverse events.14

Procalcitonin may be used in conjunction with other clinical findings to guide the management of pneumonia in children. Values less than 0.25 ng per mL can accurately identify children at lower risk of bacterial CAP for whom antibiotics are unlikely to be helpful.15,16

Complete blood count and levels of acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are not typically obtained in the outpatient setting. However, they may be beneficial for management decisions in more severely ill children in the hospital setting, according to Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines.11 Measurement of C-reactive protein in general practice settings for children with nonsevere acute infections has not been shown to reduce antibiotic prescribing and is not recommended.17

Blood cultures should not be performed routinely in nontoxic, fully immunized children in the outpatient setting.11 Blood cultures should be obtained in hospitalized patients, but even in this setting, a pathogen is identified in only 2% to 7% of children with CAP.11,18

Sputum cultures are difficult to obtain in children and have low diagnostic yield.11

Physicians should have appropriate suspicion and consider testing for COVID-19, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, or Mycoplasma pneumoniae as indicated.11,19,20

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

There is substantial overlap in the clinical and radiologic characteristics of pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and asthma.2

Atypical pneumonia has been identified in 3% to 23% of children studied, with M. pneumoniae typically found in older children and Chlamydia pneumoniae in infants.11 The clinical course of M. pneumoniae is typically slow progression of cough over three to five days with malaise, sore throat, and low-grade fever. Bilateral perihilar pulmonary infiltrates and wheezing should raise suspicion for these pathogens.11

Complications associated with CAP include pulmonary complications, such as pleural effusion or empyema, and systemic complications, such as sepsis.11

Treatment

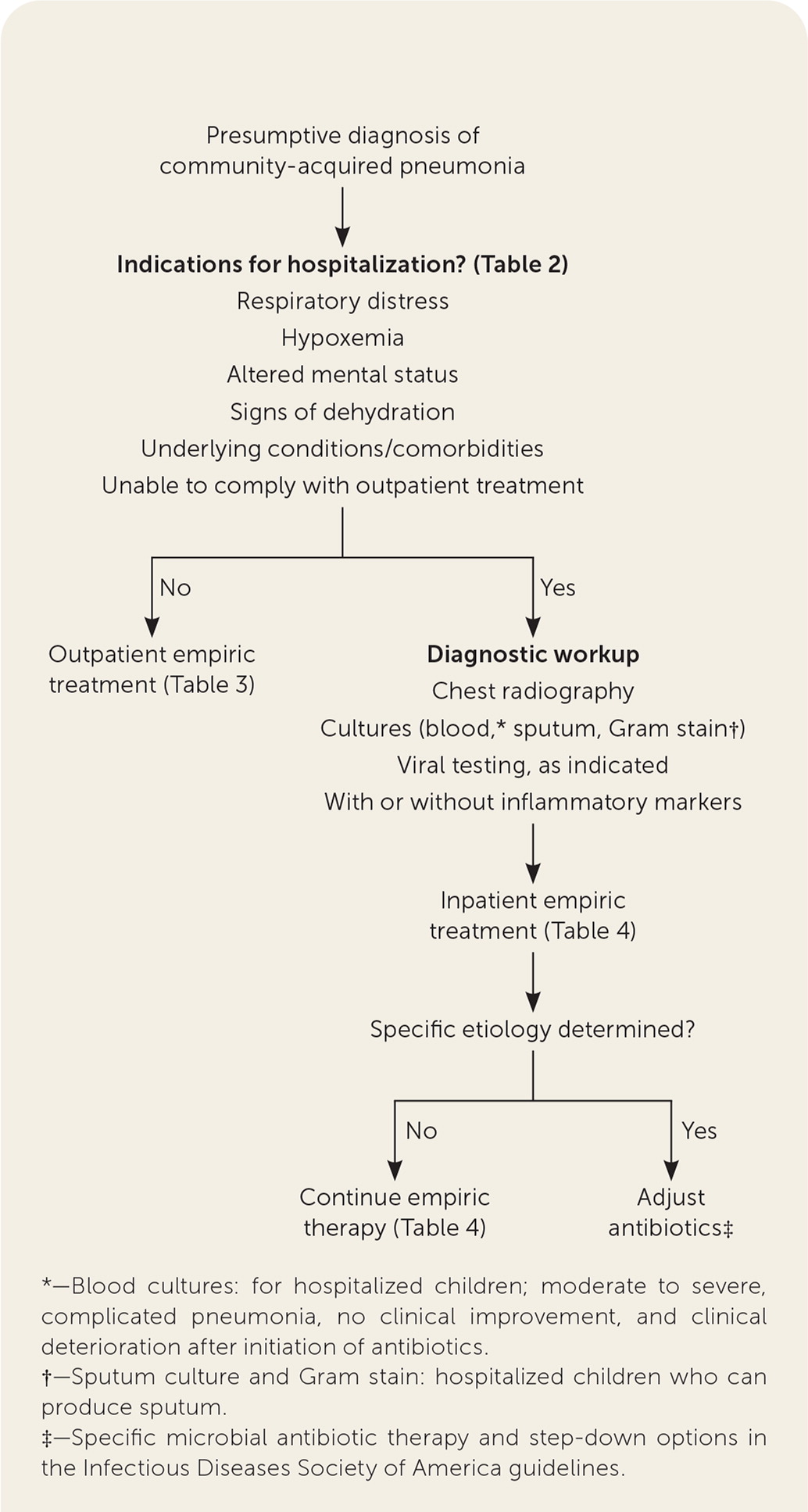

INPATIENT VS. OUTPATIENT TREATMENT

| Altered mental status |

| Children and infants with concern about careful observation at home or with caregivers who are unable to comply with therapy or follow-up |

| Hypoxemia < 90% to 92% |

| Infants younger than 3 to 6 months with suspected bacterial infection |

| Respiratory distress: tachypnea, dyspnea, apnea, grunting, retractions, nasal flaring, altered mental status, apnea |

| Signs of dehydration |

| Suspected or confirmed infection with a virulent organism such as community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or group A Streptococcus |

| Tachypnea |

| Newborn to 2 months of age, respiratory rate > 60 bpm |

| 2 to 12 months of age, respiratory rate > 50 bpm |

| 1 to 5 years of age, respiratory rate > 40 bpm |

| Underlying conditions/comorbidities |

| May predispose patients to more serious course (e.g., cardiopulmonary disease, genetic syndromes, neurocognitive disorders) |

| May be worsened by pneumonia (e.g., metabolic disorders) |

| May adversely affect response to treatment (e.g., immunocompromised host, sickle cell disease) |

SUPPORTIVE THERAPY

CHOICE OF ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

Initial antimicrobial therapy is not recommended routinely in preschool-aged children with pneumonia because viruses are the predominant pathogen in this population.22

In a meta-analysis of 29 studies of antibiotic treatment for pneumonia in children, 14 studies reported that bacterial pathogens could be isolated in only 12% of participants; S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae constituted 65% of those bacterial isolates.23

Amoxicillin is the first-line choice of oral empiric treatment in school-aged children with coverage for S. pneumoniae23; Table 3 lists other options.11

IDSA guidelines recommend the use of macrolide antibiotics for the treatment of atypical pneumonia in children, although the data are conflicting.11 Macrolide use must be weighed against the risk of increasing resistance in S. pneumoniae and M. pneumoniae.11,24,25

Children who are not responding to initial therapy after 48 to 72 hours should have clinical reassessment of the severity of illness and anticipated progress to determine level of care.11

Empiric parenteral therapy is based on patient vaccination status against S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae type b (Table 4).11

When a bacterial pathogen is identified in blood or pleural fluid cultures, sensitivities should guide therapy.11

| Patients younger than 5 years | ||

| Presumed bacterial cause First-line: amoxicillin Alternative: amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) | Presumed atypical cause First-line: azithromycin (Zithromax) Alternative: clarithromycin (Biaxin) | Presumed influenza pneumonia Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) |

| Patients 5 years and older | ||

| Presumed bacterial cause First-line: amoxicillin Alternative: amoxicillin/clavulanate | Presumed atypical cause First-line: azithromycin Alternative: clarithromycin or erythromycin; doxycycline for children older than 7 years | Presumed influenza pneumonia Oseltamivir or zanamivir (Relenza) |

| Children fully immunized against Haemophilis influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae | ||

|---|---|---|

| Presumed bacterial cause First-line: ampicillin or penicillin G Alternatives: ceftriaxone or cefotaxime (Claforan) Suspected community-acquired MRSA: add vancomycin or clindamycin | Presumed atypical cause First-line: azithromycin (Zithromax) Alternatives: clarithromycin (Biaxin) or erythromycin Consider adding a beta lactam if diagnosis of atypical pneumonia is in doubt | Presumed influenza pneumonia Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir (Relenza) |

| Children not fully immunized against H. influenzae type b and S. pneumoniae | ||

| Presumed bacterial cause First-line: ceftriaxone or cefotaxime Alternative: levofloxacin (Levaquin; use with caution in children who have not reached skeletal maturity) Suspected community-acquired MRSA: add vancomycin or clindamycin | Presumed atypical cause First-line: azithromycin Alternatives: clarithromycin or erythromycin; doxycycline for children older than 7 years; levofloxacin for children who have reached skeletal maturity or who cannot tolerate macrolide antibiotics Consider adding a beta lactam if diagnosis of atypical pneumonia is in doubt | Presumed influenza pneumonia Oseltamivir or zanamivir |

DURATION AND ROUTE OF THERAPY

Outpatient therapy for uncomplicated CAP should not exceed seven days.26 A comparative effectiveness study of 439 children six months or older hospitalized for uncomplicated CAP at The Johns Hopkins Hospital between 2012 and 2018 found a 4% treatment failure.27 Of those with treatment failure, no differences were observed between patients who received a short course (median = six days) vs. a prolonged course (median = 10 days) of treatment (OR = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.18 to 1.30).27

Inpatient intravenous therapy should be transitioned to oral antibiotics once the patient is clinically improving and able to tolerate oral intake. Outcomes of treatment with oral antibiotics are similar to those of treatment with parenteral ampicillin or penicillin, even in children with severe pneumonia.23

Prevention

Childhood immunizations should be used for the prevention of CAP caused by bacterial pathogens—S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae type b, and Bordetella pertussis.11

Annual influenza virus immunization should be performed in patients six months or older, including parents and caretakers of infants six months or younger.11

Maternal immunization with tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended between 27 and 36 weeks' gestation in each pregnancy to maximize maternal antibody response and passive antibody transfer to newborns.28

Palivizumab (Synagis) decreases risk of hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus in high-risk infants based on prematurity and/or cardiopulmonary comorbidity.29

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Stuckey-Schrock, et al.,30 and by Ostapchuk, et al.31

Data Sources: A PubMed literature search was completed using pneumonia, pediatric pneumonia, and pediatric lower respiratory tract infection. Relevant articles were cross-referenced in PubMed and reviewed for relevance. An Essential Evidence Plus summary on pneumonia was reviewed. References from articles were reviewed for primary-source evidence. Search dates: August to September 2020, February to March 2021, and July 2021.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

We are military service members. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person's official duties.