Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(6):626-635

Related Letter to the Editor: Simplification in Hepatitis C Treatment

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Screening recommendations and treatment guidelines for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection have been updated. People at the greatest risk of HCV infection are those between 18 and 39 years of age and those who use injection drugs. Universal screening with an anti-HCV antibody test with follow-up reflex HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction testing for positive results to confirm active disease is recommended at least once for all adults 18 years and older and during each pregnancy. Any person with ongoing risk factors should be screened periodically as long as the at-risk behavior persists. One-time screening is recommended for patients younger than 18 years with risk factors. For treatment-naive adults without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, a simplified treatment regimen consisting of eight weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir results in greater than 95% cure rates. Undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after completing therapy is considered a virologic cure (i.e., sustained virologic response). A sustained virologic response is associated with lower all-cause mortality and improves hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations, cognitive function, physical health, work productivity, and quality of life. In patients with compensated cirrhosis, posttreatment surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices should include abdominal ultrasonography (with or without alpha fetoprotein) every six months and upper endoscopy every two to three years. In the absence of cirrhosis, no liver-related follow-up is recommended.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, an underdiagnosed and undertreated multifaceted systemic disease, has a protracted chronic phase with hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations that affects an estimated 3.7 million people in the United States.1–5 From 2010 to 2018, the incidence of acute HCV infection among people 18 to 39 years of age quadrupled because of the opioid epidemic and the associated increase in people who inject drugs.1–8 Globally, less than 5% of people with HCV have been diagnosed, and less than 1% have received treatment.1,6,7

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not repeat hepatitis C virus antibody testing in patients with a previous positive hepatitis C virus test result. Instead, order hepatitis C viral load testing for assessment of active vs. resolved infection. | American Society for Clinical Pathology |

| Do not repeat hepatitis C viral load testing outside of antiviral therapy. | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases |

The World Health Organization and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have developed strategies to eliminate HCV by 2030.1,6,7 Strategies include expanded screening, better access to appropriate care, and highly effective direct-acting antiviral medication.1,6,7 The United States is not on track to meet this goal.1,4,6,7 Estimates for 2018 indicated that 52% of people in the United States were aware of their disease, and 37% had received treatment.4 Current barriers to access and treatment include the asymptomatic nature of chronic HCV, lack of access to specialty care, high cost of treatment, insurance guidelines requiring advanced stages of liver fibrosis before approving therapy, substance use and sobriety requirements, and prescriber restrictions (https://stateofhepc.org/).1,6–15

Transmission

Injection drug use accounts for approximately 60% of acute HCV infections in the United States.1,2,8,15 Men who have sex with men (particularly people with HIV or those who have unprotected anal intercourse), perinatal transmission, and exposure to blood products before 1992 are other sources.2,8,15,16 Nosocomial exposure (e.g., hemodialysis, needlestick) and cosmetic exposure (e.g., tattooing, piercing) are less likely routes of transmission if standard infection-control practices are followed8,15 (Table 12,8,15–18).

| Community exposure |

| Incarceration |

| Infants born to a person with hepatitis C virus infection |

| Injection drug use |

| Men who have sex with men (particularly people with HIV or those who have unprotected anal intercourse) |

| Percutaneous or parenteral exposure in an unregulated setting with poor infection control practices |

| Hospital exposure |

| Long-term hemodialysis |

| Needlestick injuries |

| Receipt of clotting factor concentrate in the United States before 1987 |

| Transfusion of blood products before 1992 |

| Other |

| HIV or hepatitis B infection |

| Sexually active person starting pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV |

| Unexplained chronic hepatic disease including abnormal liver enzymes (mild, intermittent or markedly elevated) |

Screening

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends universal HCV screening at least once for all adults 18 years and older and during each pregnancy 19 (Table 2).17 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all pregnant individuals during each pregnancy.20 People at risk, or those who request testing, should be screened periodically for as long as the at-risk behavior persists.17 One-time screening is recommended for patients younger than 18 years with risk factors.17 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening all asymptomatic adults (including people who are pregnant) 18 to 79 years of age and people younger or older who are at high risk of infection.21 Anti-HCV antibody testing (third-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with 99% sensitivity and specificity) is the screening test of choice with follow-up reflex HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction testing for positive results to confirm the active disease.8,15,17 Point-of-care testing allows for expanded screening.8,22 The OraQuick HCV rapid antibody test is a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–waived point-of-care test with reliable results (sensitivity, 94.1%; specificity, 99.5%; positive predictive value, 72.7%; and negative predictive value, 99.9%).8,22

| Universal HCV screening: |

| HCV screening at least once in a lifetime for all adults ≥ 18 years, except in settings where the prevalence of HCV infection (HCV RNA-positivity) is < 0.1%* |

| HCV screening for all pregnant people during each pregnancy, except in settings where the prevalence of HCV infection (HCV RNA-positivity) is < 0.1%* |

| One-time HCV testing regardless of age or setting prevalence among people with recognized risk factors or exposures: |

| People with HIV |

| People who ever injected drugs and shared needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment, including those who injected once or a few times many years ago |

| People with select medical conditions, including people who ever received maintenance hemodialysis, and people with persistently abnormal alanine transaminase levels |

| Recipients of transfusions or organ transplants, including people who received clotting factor concentrates produced before 1987, people who received a transfusion of blood or blood components before July 1992, people who received an organ transplant before July 1992, and people who were notified that they received blood from a donor who later tested positive for HCV infection |

| Health care, emergency medical, and public safety personnel after needlesticks, sharps, or mucosal exposures to HCV-positive blood |

| Children born to mothers with HCV infection |

| Routine periodic testing for people with ongoing risk factors, while risk factors persist: |

| People who currently inject drugs and share needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment |

| People with select medical conditions, including people who ever received maintenance hemodialysis |

| Any person who requests HCV testing should receive it, regardless of disclosure of risk, because many people might be reluctant to disclose stigmatizing risks |

Acute HCV Infection

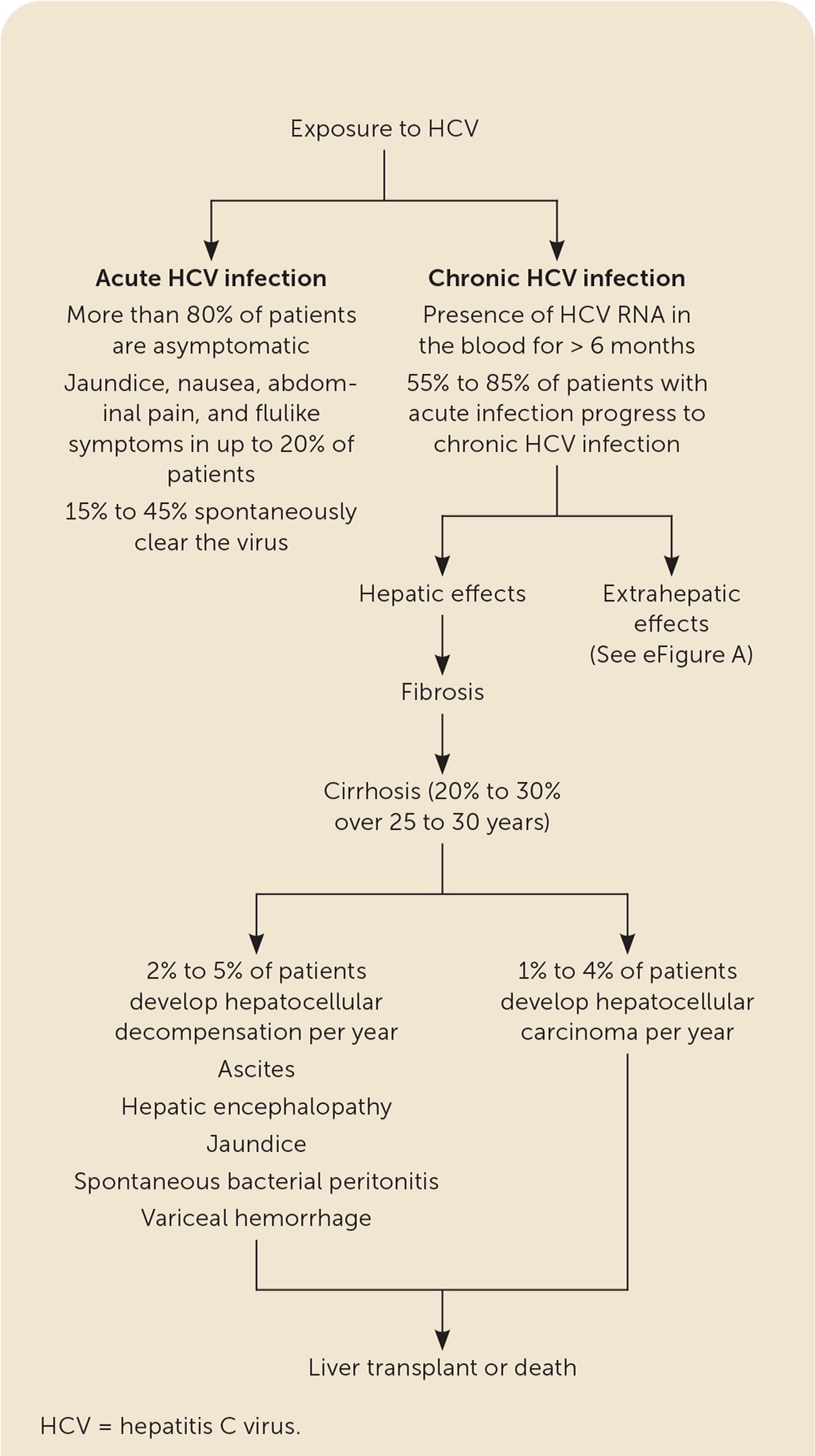

Most patients with acute HCV infection are asymptomatic. Anorexia, malaise, jaundice, and abdominal pain occur in 10% to 20% of patients two to 12 weeks after exposure.11,15,17,23 The HCV antibody becomes detectable four to 10 weeks after exposure and is present in 97% of patients by six months.17,23 A positive HCV antibody test reflects active disease, a resolved infection, or a rare false-positive result.24 The presence of HCV RNA indicates acute infection and can be present as early as one to two weeks after exposure.23,25 Alanine transaminase levels peak at 10 to 20 times the upper limit of normal, typically rising eight to 10 weeks after infection.23 Once infected, 15% to 45% of patients spontaneously clear the virus8,15,23,25 (Figure 18,15,22,23,26–30). Factors associated with an increased rate of clearance include younger age, jaundice, elevated alanine transaminase level, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity, female sex, HCV genotype 1, and host genetic polymorphisms (i.e., IL28B gene).15,17,23,31,32 Clearance rates are lower in patients with HIV infection.17,23

Chronic HCV Infection

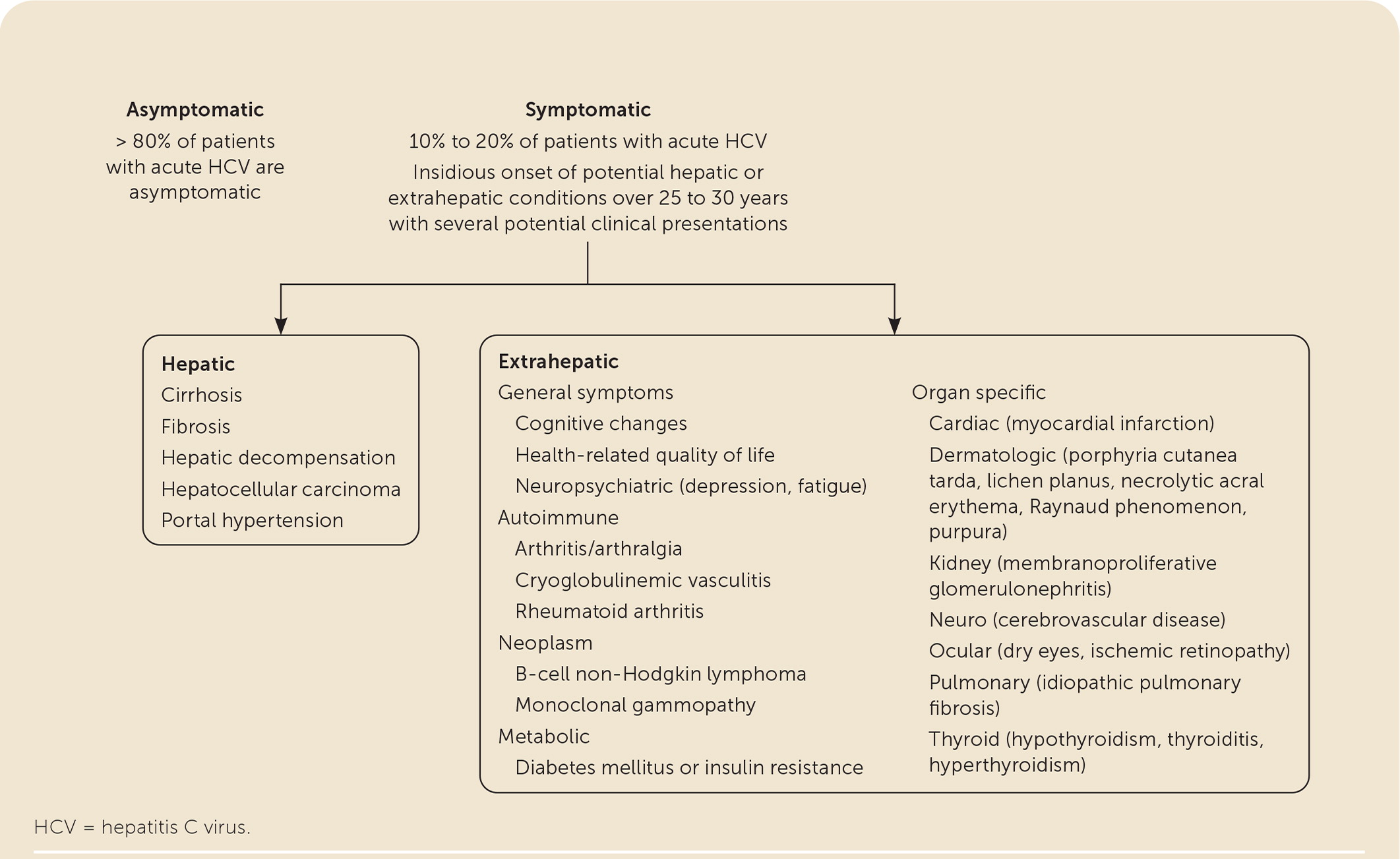

The persistence of HCV RNA after six months indicates chronic HCV infection. Although chronic HCV is insidious with few symptoms or physical signs, two quality-of-life studies highlight symptom clusters (i.e., neuropsychiatric, gastrointestinal, algesic, and dysesthetic) in treatment-naive patients with chronic HCV33,34 (eTable A).

| Algesic General body pain Joint pain Muscle pain Dysesthetic Headaches Light sensitivity Noise sensitivity Skin problems Gastrointestinal Abdominal pain Day sweats Diarrhea Food intolerance Nausea Night sweats Poor appetite Neuropsychiatric Depression Forgetfulness Irritability Mental tiredness Physical tiredness Poor concentration Sleep problems |

Hepatic sequelae include chronic hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).8,15,23 Fulminant hepatitis usually does not occur.15 Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with chronic HCV develop cirrhosis over 25 to 30 years.23 Risk factors for cirrhosis include male sex, being older than 50 years, hepatitis B virus infection, HIV infection, immunosuppressive therapy, alcohol use, obesity, hepatotoxic drugs, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.15,23,26 Elevated bilirubin level, hypoalbuminemia, prolonged prothrombin time, or decreased platelet count suggests cirrhosis.35–37 Patients with cirrhosis are at greater risk of developing HCC (1% to 4% per year) and hepatocellular decompensation (2% to 5% per year) manifested by ascites, encephalopathy, jaundice, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or variceal hemorrhage.23,27,28,38–40

Up to 74% of patients develop an extrahepatic manifestation, several of which can negatively impact quality of life8,15,27–30,40,41 (eFigure A). The fourfold increase of diabetes mellitus contributes to accelerated liver fibrosis and an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease.29,30 Direct-acting antiviral therapy is helpful for many extrahepatic conditions.8,15,27–30,42

Pretreatment Assessment

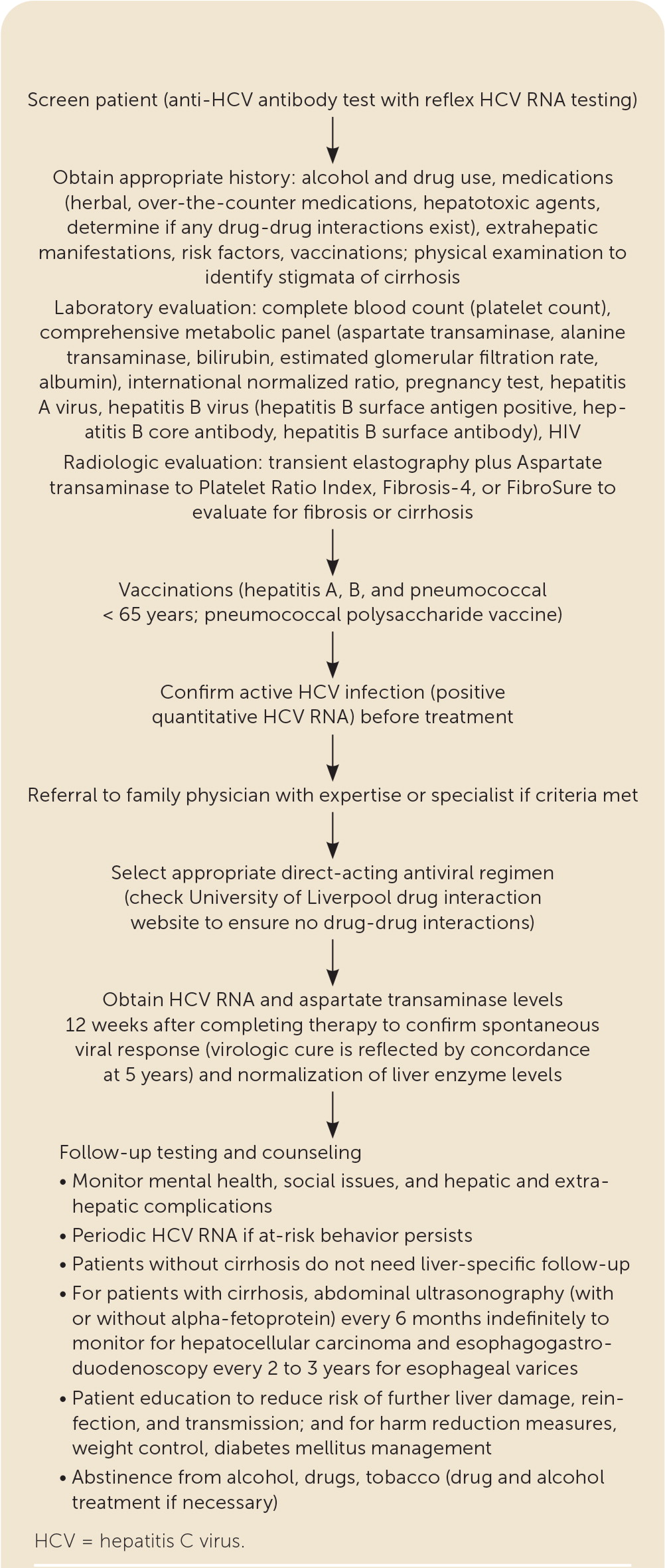

The pretreatment assessment begins with a complete medical history that includes identifying alcohol and drug use, potential drug-drug interactions, hepatotoxic agents, comorbid conditions, risk factors, prior treatment, and the need for vaccinations8,15,17,42–45 (Figure 28,15,42–45). Noninvasive testing such as transient elastography with an indirect marker of fibrosis (e.g., Aspartate transaminase to Platelet Ratio Index [APRI], Fibrosis-4 [FIB-4], Fibrosure) can be used to determine the extent of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis8,15,37,40 (Table 38,15,18). Laboratory testing includes a quantitative HCV RNA, HIV, liver panel (aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, bilirubin, albumin), complete blood count, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) measurement, and pregnancy testing.8,15,16,42 Because all direct-acting antiviral medications carry a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) boxed warning for the risk of hepatitis B reactivation in coinfected patients, testing is recommended for current (HBsAg positive) and past (hepatitis B surface antibody [anti-HBs] and hepatitis B core antibody [anti-HBc]) hepatitis B virus infection before therapy.8,15 Vaccination against hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and pneumococcal disease (pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults 19 to 64 years of age) should be administered to people with chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, or HCV.8,15,17

| Serum markers | Components | Metrics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartate transaminase to Platelet Ratio Index score | Aspartate transaminase level, platelet count | ≥ 0.7 U per L (0.01 μkat per L) has sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 72% for detecting F2 fibrosis or greater Cutoff of at least 1 has sensitivity of 61% to 76% and specificity of 64% to 72% for F3, F4 fibrosis/cirrhosis Cutoff of at least 2 has a sensitivity of 46% and specificity of 91% for cirrhosis | Predicts severe fibrosis and cirrhosis or low risk of fibrosis or cirrhosis but does not differentiate intermediate stages from severe fibrosis |

| Fibrosure (combination of Fibrotest and Actitest) | Age, sex, alpha-2-macroglobulin, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein A1C, gamma-glutamyl transferase, total bilirubin | Mild, significant, or intermediate | Fibrotest estimates hepaticfibrosisActitest indicates hepatic inflammation (high specificity for significant fibrosis) |

| Fibrosis-4 | Alanine transaminase level, aspartate transaminase level, platelet count, age | Score < 1.45 has 74% sensitivity and a negative predictive value of 95% for excluding advanced fibrosis (F3 or F4) Score > 3.25 has a positive predictive value of 82% and specificity of 98% in confirming cirrhosis Score = 1.45 to 3.25 requires another test to confirm fibrosis | Good at confirming or excluding cirrhosis if score > 3.25 |

| Direct serum markers | Procollagen type (I, III, IV), matrix metalloproteinases, cytokines, chemokines | Variable effectiveness in predicting liver fibrosis | To be determined |

| Radiologic assessment | |||

| Fibroscan (transient elastography) | Transducer probe mounted on axis of a vibrator | > 12.5 kPa has high sensitivity (87%) and specificity (91%) for cirrhosis | Detection of advanced fibrosis (F3, F4) and cirrhosis |

Treatment and Outcome Overview

Direct-acting antiviral therapy is more effective, better tolerated, and the treatment course is shorter than older interferon and ribavirin-based regimens. The need for pretreatment genotyping and on-treatment monitoring is decreased with these agents.15,40,46,47 As a prevention strategy, the test-and-treat option calls for treatment at the time of diagnosis, instead of waiting for spontaneous resolution of the acute infection in all patients except those with a life expectancy of less than one year.8,15,47 Undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after completion of treatment indicates a sustained virologic response and is indicative of a virologic cure as reflected by the high concordance at the five-year mark.8,15,27,47–49 A sustained virologic response is associated with lower all-cause mortality and improves hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations, cognitive function, physical health, work productivity, and quality of life.8,15,40,41,47,49–52

DIRECT-ACTING ANTIVIRAL MEDICATION

FDA-approved pangenotypic direct-acting antiviral treatments include glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret), sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa), and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir (Vosevi).8,15,18,40,42,47,53 Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir are the direct-acting antiviral medications that comprise the simplified treatment regimens recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America and are the focus of this article8,15,18,47,54–56 (Table 48,15,18,40,42,53,56).

| Regimen | Mechanism of action | Genotype | Dosage | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret; 100 mg/40 mg [total per day = 300 mg/120 mg]) | NS3/4A, NS5A | 1 through 6 | 3 tablets per day for 8 weeks | Not available ($25,000) |

| Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa; 400 mg/100 mg) | NS5A, NS5B | 1 through 6 no evidence of cirrhosis; 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 for compensated cirrhosis† | 1 tablet per day for 12 weeks | $11,000 ($70,000) |

Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir is indicated for patients without cirrhosis and for those with compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh classification A; Table 5).8,15,18 Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir is not recommended in Child-Pugh classification B cirrhosis and is contraindicated in Child-Pugh classification C cirrhosis.8,15,18 There is no restriction based on renal function.8,15,18 Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir is used for patients without cirrhosis and patients with compensated cirrhosis, including Child-Pugh classification B cirrhosis and Child-Pugh classification C cirrhosis (with ribavirin).8,15,18 Based on recent studies, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir is now approved for use in patients with an eGFR of 30 mL per minute per m2 or less and patients on hemodialysis.8,15,57 The most common adverse effects include fatigue, headache, insomnia, and nausea.8,15,18,42,47 Only 1% to 2% of patients discontinue treatment because of adverse events.8,15,18

| +1 | +2 | +3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin | > 3.5 g per dL (35 g per L) | 2.8 to 3.5 g per dL (28 to 35 g per L) | < 2.8 g per dL |

| Ascites | None | Mild to moderate | Severe |

| Bilirubin | < 2 mg per L (34.21 μmol per L) | 2 to 3 mg per L (34.21 to 51.31 μmol per L) | > 3 mg per L |

| Encephalopathy | None | Mild to moderate | Severe |

| International normalized ratio | < 1.7 | 1.7 to 2.3 | > 2.3 |

DRUG-DRUG INTERACTIONS

Herbal and dietary supplements should be discontinued.18,42 Acetaminophen is generally safe if less than 2 g per day is used.8,15 The blood glucose level and international normalized ratio (INR) should be closely monitored to prevent hypoglycemia and subtherapeutic INR levels.8,15,44,45 The opioid use disorder treatments methadone, buprenorphine, and buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone) do not have significant interactions with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir 8,15,18,42,43,45–47,53 (eTable B).

| Drug | Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret) | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa) |

|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | Safe to use | Unsafe to use (life-threatening bradycardia) |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | Unsafe to use | Unsafe to use |

| Diabetes mellitus medications | Monitor to prevent hypoglycemia | Monitor to prevent hypoglycemia |

| Ethinyl estradiol–containing contraceptives | Unsafe to use | Safe to use |

| Herbal medicine | Unsafe to use | Unsafe to use |

| Methadone, buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone) | Safe to use | Safe to use |

| Proton pump inhibitors | Safe to use | Unsafe to use (if must use, should be taken with food 4 hours before 20-mg omeprazole [Prilosec]) |

| Statins | Unsafe to use with atorvastatin (Lipitor), lovastatin (Mevaor), or simvastatin (Zocor; increased statin levels leading to myopathy and rhabdomyolysis) | Safe to use atorvastatin and rosuvastatin (Crestor) at low doses (monitor for myopathy and rhabdomyolysis) |

| St. John's wort | Unsafe to use | Unsafe to use |

| Warfarin (Coumadin) | Monitor for subtherapeutic international normalized ratio levels | Monitor for subtherapeutic international normalized ratio levels |

OPTIONS FOR TREATMENT-NAIVE HCV WITHOUT CIRRHOSIS OR WITH COMPENSATED CIRRHOSIS

In adults with HCV and without cirrhosis who meet criteria for treatment with the simplified regimen, studies have consistently exhibited a greater than 95% sustained viral response at 12 weeks posttreatment with eight weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, regardless of the HCV genotype.8,15,18,40,54

Patients with treatment-naive HCV with compensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh classification A) who qualify for the simplified treatment regimen need a clinical evaluation to rule out ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. Abdominal ultrasonography within six months of starting treatment is required to exclude HCC and subclinical ascites.8,15,18 Any evidence of hepatic decompensation or HCC is a contraindication for the simplified treatment regimen and requires a referral.8,15 Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir have shown similar high curative rates to patients without cirrhosis.8,15,18,54,55 Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir is effective against all HCV genotypes.8,15,18 If sofosbuvir/velpatasvir is selected, pretreatment genotype testing to identify patients with genotype 3 is required to eliminate possible nonstructural protein 5A resistance-associated substitution at Y93H.8,15,54 If the resistance-associated substitution result is positive, patients should be treated with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or referred to a specialist.8,15,18 Because hepatic decompensation occurs rarely during treatment of HCV infection, a complete blood count; measurement of alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, bilirubin, and albumin levels; INR; and eGFR should be obtained within three months of initiating treatment to detect early liver injury.8,15,18

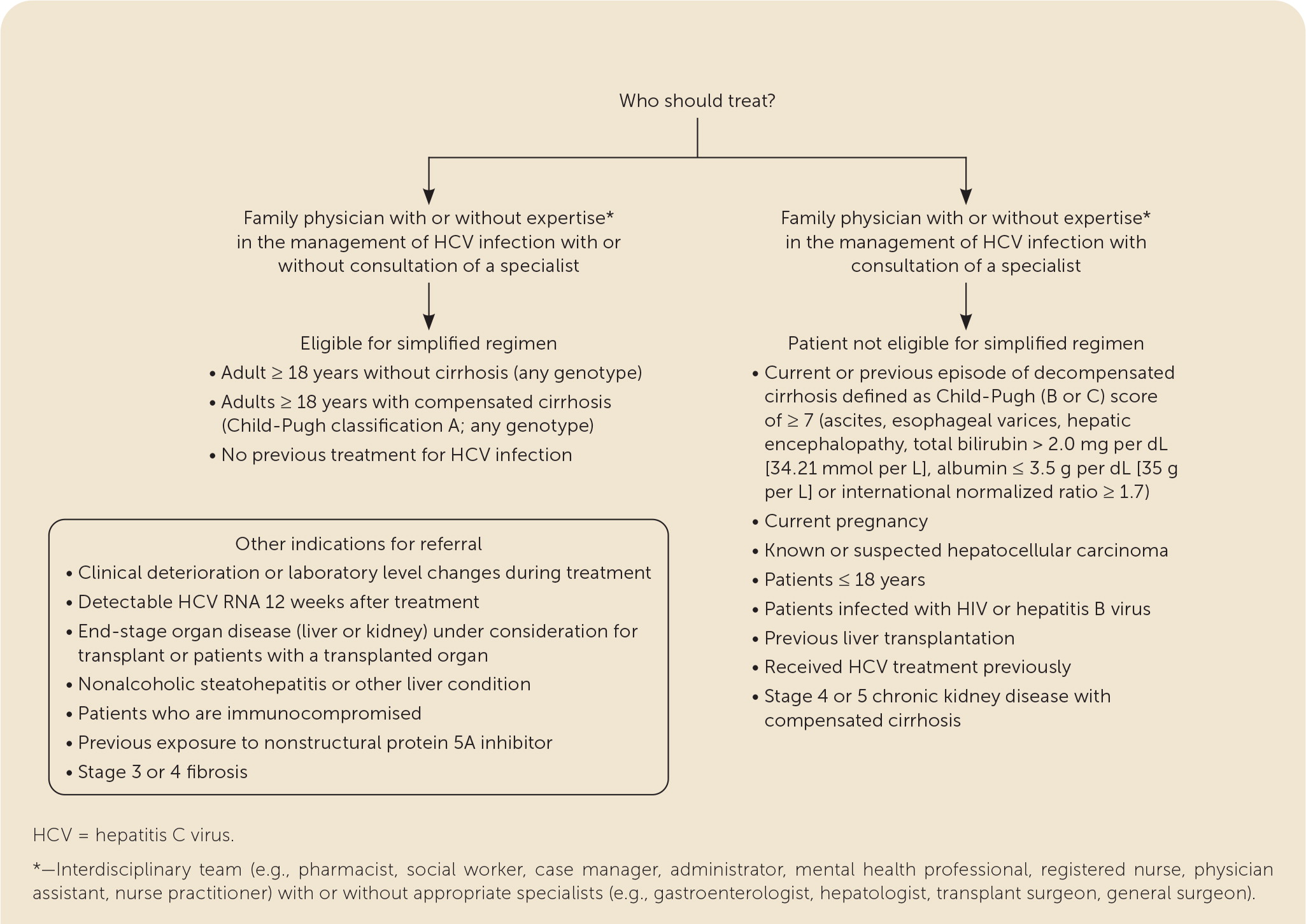

FAMILY MEDICINE VS. SPECIALTY CARE

Specialty consultants serving as mentors to primary care physicians through videoconferencing were used in Project ECHO to provide treatment for patients with HCV in rural communities across New Mexico.7–10,12–14 In the ASCEND study, primary care physicians and nurse practitioners treated a cohort of patients at several urban federally qualified health centers.8–14 Both studies demonstrated that nonspecialists could provide safe, effective HCV treatment with outcomes equivalent to specialists.8–15

Family physicians can provide greater access to treatment, comparable treatment outcomes to specialists, and comprehensive posttreatment continuity of care.1,2,6–15 Family physicians with expertise in multiple treatment regimens and coinfections or comorbidities can continue to treat or comanage their patients8,11,13,15,48,58 (eFigure B).

Treatment Failure

Patients with clinical deterioration or laboratory changes during treatment should be promptly referred. Once a patient achieves sustained virologic response after 12 weeks of treatment, any detectable amount of HCV RNA indicates reinfection or relapse.8,48,58–60 Patients who are reinfected (continued at-risk behavior with subsequent positive HCV RNA) can be treated with the simplified regimen.8 If relapse (usually within 12 weeks of sustained virologic response) is a consideration, the patient should be referred to a specialist for genotypic testing and treatment.8,48,58–60 Patients with persistently elevated transaminase levels after sustained virologic response should be evaluated for other causes of hepatic disease.8,15,18,61–63

Posttreatment Management

No liver-specific follow-up is recommended for patients without cirrhosis.8,15,17,18 For patients with cirrhosis, surveillance is recommended indefinitely for HCC and esophageal varices. Surveillance consists of abdominal ultrasonography (with or without alpha fetoprotein) every six months and upper endoscopy every two to three years, depending on the initial endoscopy results.8,15,18,49

Access to community resources and appropriate addiction, medical, psychiatric, and preventive services with long-term monitoring of patients for the early identification and management of hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations, reinfection, or other medical, psychiatric, and social issues is important.8,15,41,57 Patients should avoid alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs.8,15 Harm-reduction interventions, risk reduction, and liver-protective measures are necessary to prevent reinfection and additional liver damage8,15,17,18,42 (Table 61,8,15–18,42,48,63). HCV RNA testing is indicated periodically for people with ongoing at-risk behavior and anytime an increase in transaminase levels occurs.8,15,18

| Comorbid conditions Hepatic or extrahepatic manifestations, and any medical conditions that affect the liver Obesity, diabetes mellitus, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (weight loss is essential) Diet, drugs, and tobacco Avoid alcohol, quit smoking, and avoid cannabis use Avoid hepatotoxic drugs (complementary, herbal, supplemental, over-the-counter, prescribed) Balanced low-fat diet with target body mass index < 25 kg per m2 Coffee (3 cups per day is thought to be liver protective) Less than 2,000 mg salt per day Household transmission Rare form of transmission; family members should avoid blood-contaminated items (e.g., razors, toothbrushes, nail clippers) Injection drug use Addiction treatment if necessary Avoid nonregulated tattoo parlors Counseling for drug and alcohol misuse (2% to 3% per year reinfection rate for injection drug use)* Do not donate blood, organs, or semen Harm-reduction measures (opioid agonist therapy and needle/syringe exchange) Inform patient of measures to decrease risk of transmission Perinatal transmission Breastfeeding is safe when nipples are not damaged, cracked, or bleeding Maternal HCV antibody passively transfers and can be present for up to 18 months after delivery Mode of delivery does not matter for preventing transmission Transmission occurs in 5.8% of pregnancies Periodic HCV RNA testing for people with continued at-risk behavior* Psychiatric Anxiety/depression/mental health issues/substance abuse Behavior issues/modification Sexual exposure Heterosexual transmission is low; therefore, patients in long-term monogamous relationships do not need to alter their sex practices based on HCV infection alone Men who have sex with men who have HCV should be advised to use latex condoms and avoid rough sex People starting pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV People with HIV/HCV coinfection should be encouraged to use barrier precautions (3% per year reinfection rate)* People with multiple sex partners should be encouraged to use barrier precautions |

The article updates previous articles on this topic by Moyer, et al.,64 Ward, et al.,65 Wilkins, et al.,66 and Wilkins, et al.2

Data Sources: An online search was conducted using the key terms hepatitis C, acute HCV infection, chronic HCV infection, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic decompensation, transmission, risk factors, elevated liver enzymes, anti-HCV antibody testing, HCV RNA, WHO guidelines, NASEM guidelines, hepatic and extrahepatic complications, HCV quality of life, DAA therapy, diagnosis and management of HCV, complications of HCV, coinfections and morbidity, AASLD-IDSA guidelines, screening guidelines for HCV, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, pretreatment assessment, follow-up after treatment, cost, when to refer HCV, family medicine's role, and hepatitis B and HIV. A broad-based search of the topic was performed in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, ClinicalTrials.gov, HCV guidelines, PubMed, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The search was later refined to identify major scholarly and professional resources using the following databases: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, PubMed, the Cochrane database, and OVID. Search dates: October 1, 2020, and February 19 to May 28, 2021.