Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(5):286-293

Related editorial: HIV Status, Preexposure Prophylaxis, Sexual Health, and the Critical Role of Family Physicians

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Family physicians should use a proactive, integrated, patient-centered approach to sexual health that includes, but is not limited to, disease identification and treatment. Successfully delivering positive, affirming, nonjudgmental sexual health care requires intentionally creating safe spaces for all patients. Physician and staff training could include identifying individual implicit bias around sexuality and sexual topics, adverse childhood experiences, and trauma-informed care. Models such as the five Ps (partners, practices, protection from sexually transmitted diseases, past history of sexually transmitted diseases, and pregnancy plans) and ExPLISSIT (extended permission giving, limited information, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy) can help physicians organize their approach to sexual health histories. Preventive health strategies include screening for sexually transmitted diseases and sexually transmitted infections, screening for and offering preexposure prophylaxis for HIV, behavioral counseling to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infections, and preconception care for all patients, including gender-diverse patients. Because sexual health concerns are quite common, family physicians should be prepared to discuss topics such as erectile dysfunction, dyspareunia, and arousal disorders.

Sexual health is defined by the World Health Organization as “a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity.”1 Sexual health is foundational to the physical, emotional, and social health of individuals, families, and communities. It encompasses a wide range of topics, including knowledge about anatomy and function, sexuality, sexual identity, sexual orientation and gender, reproductive health and fertility, and sexual violence.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Clinicians and staff should be trained in culturally sensitive terminology, transgender topics, cultural humility, and assessment of personal internal biases to facilitate improved patient interactions.4 | C | Consensus guidelines based on expert opinion and limited clinical studies |

| Intensive behavioral counseling should be offered to all sexually active adolescents and to adults who are at increased risk for sexually transmitted infections.21 | B | Systematic review of variable-quality randomized controlled trials with inconsistent conclusions |

| Preexposure prophylaxis with tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) or tenofovir alone reduces the risk of acquiring HIV infection in high-risk individuals, including people in serodiscordant relationships, men who have sex with men, and other high-risk men and women.20,25 | A | Cochrane systematic review of high-quality randomized controlled trials |

Family physicians should use a proactive, integrated, patient-centered approach to sexual health that includes, but is not limited to, disease identification and treatment.2 Family physicians are in an excellent position to provide a safe environment in which patients can consensually discuss issues related to sex and sexuality across their life span.

Create a Safe Space

Physicians should engage in an initial self-assessment of their own comfort by discussing sex with various patient groups and identifying any unrecognized or implicit biases that they might have. Some physicians may benefit from undergoing a sexual attitude reassessment to explore the underlying challenges they are experiencing when talking about sex and sexuality.3 A sexual attitude reassessment is a structured group seminar typically led by a sexual health specialist designed to aid participants in identifying their attitudes and beliefs around sexuality and to help them become aware of how these attitudes and values can affect their personal and professional lives. Visit the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors, and Therapists website (https://www.aasect.org/continuing-education) for sexual attitude reassessment registration information.

Physicians should focus on creating a welcoming environment by training staff and clinicians in culturally sensitive terminology, using gender-inclusive language on forms, implicit bias, and displaying diverse images in marketing and waiting areas. Small process changes such as using the two-step method (asking two questions regarding both gender identity and sex assigned at birth) or using self-identified pronouns send signals that the practice values the experience for all patients.4 These steps build a culture that reassures patients that the practice is a confidential, safe, affirming, nonjudgmental space in which to discuss intimate topics.5

Adverse childhood experiences such as sexual abuse or trauma may affect a patient's ability to discuss sexual health topics comfortably. Physicians and staff should review the components of providing trauma-informed care to recognize and respond to patients without retraumatizing them.6 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration describes trauma-informed care as realizing that trauma has a widespread effect on individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities and applying that understanding to identify paths to recovery by recognizing the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, staff, and others in the system; integrating trauma knowledge into policies, programs, and practices; and seeking to avoid retraumatization.7

| American Academy of Family Physicians | https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/social-determinants-of-health/everyone-project.html |

| American Academy of Pediatrics | https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/resilience/Pages/ACEs-and-Toxic-Stress.aspx |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/index.html |

| National Council for Behavioral Health: Trauma-Informed Primary Care Initiative | https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/trauma-informed-primary-care-initiative-learning-community |

| Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration | https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/trauma |

Taking a Sexual History

Physicians should begin the conversation by intentionally asking patients for permission to talk about sexual health. Using a proactive sexual history to discuss and address sexual health during office visits allows patients an opportunity to share their concerns or ask questions without the embarrassment of needing to raise the topic first.2,8 Table 2 lists some key points to consider when discussing sexual health with patients.8

| Avoid moral or religious judgment of the patient's behavior |

| Avoid terms that make assumptions about sexual behavior or orientation (e.g., “How many partners have you had in the past year?” rather than “Are you monogamous?”) |

| Ensure shared understanding around terminology and pronunciation for patient concerns to avoid confusion (e.g., if the patient provides a slang term for their anatomy, gently connect the slang word to the medical terminology by answering them using the corresponding anatomy in your response) |

| Establish rapport and consent before addressing sensitive topics |

| Respect the patient's right to decline answering questions or sharing information |

| Use a sensitive tone that normalizes the topics you are discussing |

| Use neutral and inclusive terms that avoid assumptions about orientation (e.g., partner) |

The depth of the sexual history will often depend on the context of the visit; starting with a brief approach that clarifies sexual activity and directly asking whether the patient has any current sexual concerns may be useful. For example, during a follow-up visit for diabetes mellitus, a physician may choose a focused approach, asking specific questions that pertain to the presenting chief complaint. During wellness visits, a more detailed history may be considered, addressing both preventive and appropriate diagnostic questions. Physicians should use the sexual health history to identify areas for preventive counseling and conditions requiring treatment or management.

Table 3 provides a summary of common questions asked during a detailed sexual health assessment8; however, there is no standard validated comprehensive sexual health assessment tool. Exploring the patient's responses to the questions will help to determine what additional follow-up questions are needed to more fully assess risk and identify opportunities for preventive health counseling. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's guide to taking a patient's sexual history uses the five Ps model: partners, practices, protection from sexually transmitted diseases/sexually transmitted infections (STD/STI), past history of STD/STI, and pregnancy plans.9 Although many of the components of sexual health are included in the five Ps, discussions around normal anatomy and function, sexuality, sexual identity, orientation, and gender are often left out of the discussion unless specifically addressed in context. Some physicians recommend adding an additional P for pleasure, and others have simplified conversations using diagrams to assist patients in sharing behaviors.10

| General questions Are you currently sexually active? Have you ever been? What is your gender? How do you identify? What pronouns do you prefer? |

| Partners How do your partners identify? Do they identify as male, female, or another? or What are the genders of your partners? How many partners have you had in the past month? The past six months? Your lifetime? How satisfied are you with your (and/or your partner's) sexual functioning? Has there been any change in your (or your partner's) sexual desire or the frequency of sexual activity? |

| Practices What type of sexual activities do you participate in? Do you participate in vaginal sex? Oral sex? Anal sex? |

| Past history/protection from sexually transmitted diseases and sexually transmitted infections Have you ever had any sex-related diseases? Do you have, or have you ever had, any risk factors for HIV? (List blood transfusions, needle stick injuries, intravenous drug use, sexually transmitted diseases, partners who may have placed the patient at risk.) Have you ever been tested for HIV? Would you like to be? What do you do to protect yourself from contracting HIV? |

| Pregnancy plans Are you trying to become a parent? Would you like to get pregnant (or father a child)? What method do you use for contraception? |

| Pleasure Do you (or your partners) use any particular devices or substances to enhance your sexual pleasure? Do you ever have pain with intercourse? Do you have any difficulty with lubrication? Do you have any difficulty achieving orgasm? Do you have any difficulty obtaining and maintaining an erection? Do you have difficulty with ejaculation? Do you have any questions or concerns about your sexual functioning? Is there anything about your (or your partner's) sexual activity (as individuals or as a couple) that you would like to change? |

The American Academy of Pediatrics offers guidance on delivering gender-affirmative care.11 Discussing normal anatomy, function, and identity issues is an important part of delivering gender-affirmative care in all age groups.12 Physicians must become familiar with terminology and be prepared to talk with patients about sexuality, including gender and sexual orientation. Examples of gender-inclusive terminology are noted in Table 4.4,11,13

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Sex | Determination made at birth referring to a biologic category of male, female, or intersex based on sex chromosomes, genital anatomy, or hormone levels |

| Sexual orientation | Self-determined sexual identity in relation to the gender(s) to which they are attracted |

| Cisgender | Self-determined term used to describe a person whose self-determined gender is consistent with sex assigned at birth |

| Transgender | Self-determined term used to describe a person whose self-determined gender does not match sex assigned at birth or remains inconsistent over time |

| Gender identity | Self-determined sense of being along (female, male, a combination of both, somewhere in-between) or outside of a gender spectrum resulting from multiple factors such as biologic characteristics, environmental and cultural factors, and self-understanding |

| Gender expression | Signals or external ways a person expresses their gender |

| Gender perception | The way others interpret an individual's gender |

Opportunities for Prevention

A thorough sexual history helps physicians individualize screening recommendations. Preventive interventions related to sexual health include STD/STI screening, behavioral counseling, and preconception counseling and management.

STD/STI SCREENING

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has multiple STD/STI-related screening recommendations, which are noted in Table 5.14–21 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published STD/STI screening recommendations,22 and the American Academy of Family Physicians has recently published pointers and a practice manual to use in screening for STIs.23,24 For many patients, assessing risk is critical in determining their need for testing. Many of these risk factors are easily elicited using the five Ps model.

| Population | Recommendation | USPSTF grade* |

|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia and gonorrhea | ||

| Sexually active women | The USPSTF recommends screening for chlamydia in sexually active women 24 years and younger and in older women who are at increased risk of infection | B |

| Sexually active women | The USPSTF recommends screening for gonorrhea in sexually active women 24 years and younger and in older women who are at increased risk of infection | B |

| Sexually active men | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in men | I |

| Hepatitis B virus | ||

| Pregnant women | The USPSTF recommends screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women at their first prenatal visit | A |

| Persons at high risk for infection | The USPSTF recommends screening for hepatitis B virus infection in persons at high risk of infection | B |

| Hepatitis C virus | ||

| Adults at high risk | The USPSTF recommends screening for hepatitis C virus infection in persons at high risk of infection. The USPSTF also recommends offering one-time screening for hepatitis C virus infection to adults born between 1945 and 1965 | B |

| Herpes simplex virus | ||

| Asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including those who are pregnant | The USPSTF recommends against routine serologic screening for genital herpes simplex virus infection in asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including those who are pregnant | D |

| HIV | ||

| Adolescents and adults 15 to 65 years of age | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen for HIV infection in adolescents and adults 15 to 65 years of age. Younger adolescents and older adults who are at increased risk of infection should also be screened | A |

| Pregnant women | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians screen for HIV infection in all pregnant women, including those who present in labor or at delivery whose HIV status is unknown | A |

| Persons at high risk of HIV acquisition | The USPSTF recommends that clinicians offer preexposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral therapy to persons who are at high risk of HIV acquisition | A |

| Sexually transmitted infections | ||

| Sexually active adolescents and adults | The USPSTF recommends intensive behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults who are at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections | B |

| Syphilis | ||

| Asymptomatic, nonpregnant adults and adolescents who are at increased risk of syphilis infection | The USPSTF recommends screening for syphilis infection in persons who are at increased risk of infection | A |

| Pregnant women | The USPSTF recommends early screening for syphilis infection in all pregnant women | A |

BEHAVIORAL COUNSELING

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends intensive behavioral counseling to reduce the risk of STIs for all sexually active adolescents and for adults who are at increased risk of STIs.21 Intensive behavioral counseling interventions can take many forms, including in-person or web-based, single episode vs. multiple episodes, primary care setting vs. counseling setting, or individual vs. group. However, the intervention should last at least 30 minutes to be effective.21

PREEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS FOR HIV

Patients who are at high risk for HIV infection benefit from initiating preexposure prophylaxis. Once-daily treatment with tenofovir/emtricitabine (Truvada) is the only regimen currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for preexposure prophylaxis; however, some trials suggest tenofovir alone could be used as an alternative regimen in certain patient groups.20,25 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends providing preexposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral therapy to patients at high risk of acquiring HIV infection.20 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends considering preexposure prophylaxis for the following populations:

anyone who is HIV negative and in an ongoing sexual relationship with an HIV-positive partner;

anyone who is not in a mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who recently tested HIV negative and is a gay or bisexual man who has had anal sex without using a condom or has been diagnosed with an STD in the past six months;

anyone who is not in a mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who recently tested HIV negative and is a heterosexual man or woman who does not regularly use condoms during sex with partners of unknown HIV status who are at substantial risk of HIV infection (e.g., people who inject drugs, women who have bisexual male partners);

anyone who has injected drugs in the past six months and has shared needles or works or has been in drug treatment in the past six months.26

PRECONCEPTION COUNSELING

Given the rates of unintended pregnancies, disparities associated with maternal risk factors, and subsequent adverse reproductive outcomes, preconception care remains a Healthy People 2020 strategic objective.27 The American Academy of Family Physicians has provided guidance on comprehensive preconception care through a position paper,28 which was discussed in an editorial in American Family Physician.29 Fertility preservation and preconception care should also be discussed with gender-diverse patients, especially those receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy.30,31

Addressing Sexual Health Concerns

Between 50% and 98% of women report at least one sexual health concern, including interest in sex, difficulty with orgasm, inadequate lubrication, dyspareunia, body image concerns, unmet sexual needs, the need for information about sexual issues, physical and sexual abuse, and sexual coercion.32,33 Around 40% of men report at least one sexual health concern, most commonly erectile dysfunction or premature ejaculation.34

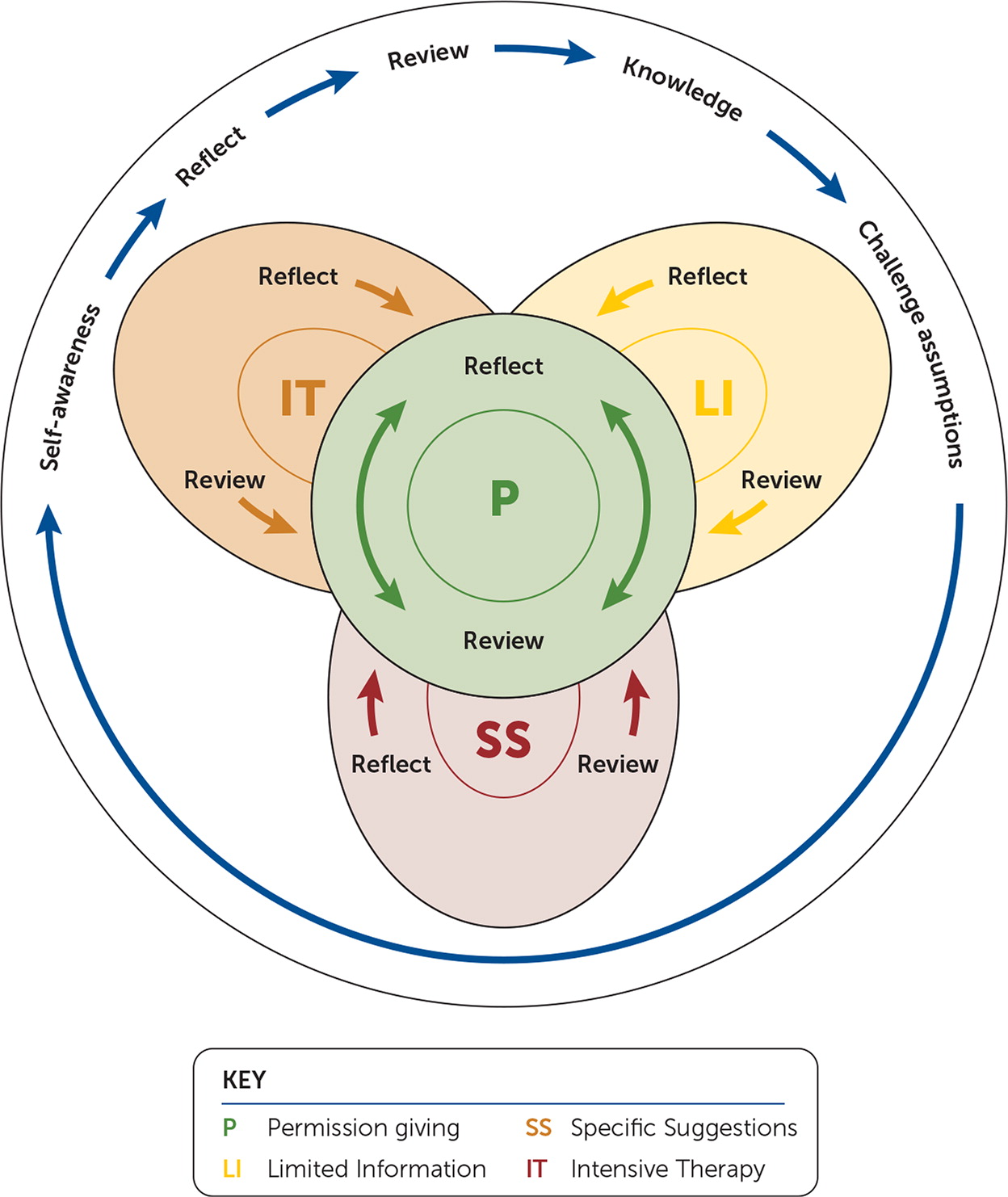

The PLISSIT (permission giving, limited information, specific suggestions, and intensive therapy) model provides an approach for addressing sexual health concerns.35 The model was recently updated (Extended PLISSIT) to better address the needs of patients with disabilities or chronic illness (Figure 1).36 Throughout the conversation, the family physician is encouraged to give the patient permission to be curious and to ask open-ended questions such as, “Many people are concerned about how this condition might affect their sex life. What is your experience?” The patient's response determines what information the physician offers about the diagnosis and sexual function connection. Physicians should confirm patient understanding before using shared decision-making to brainstorm ideas to address any specific concerns. If the discussion identifies more complicated issues that require additional assessment or treatment, appropriate referrals can be provided.

Several common sexual conditions have been reviewed in American Family Physician, including sexual dysfunction in women,37 dyspareunia,38 and erectile dysfunction. 39 Not all sexual health concerns are related to genital issues. Chronic conditions, including pulmonary disease, cardiac disease, osteoarthritis, and mental health issues, can affect sexual activity and satisfaction. Pulmonary and cardiac rehabilitation with physical and occupational therapy can improve stamina, energy conservation, balance, and core strength, which are often valuable in satisfying sexual encounters. There is no high-quality evidence supporting the effectiveness of sexual counseling for sexual problems in patients with cardiovascular disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the data are insufficient around interventions for sexual dysfunction following treatments for cancer in women, in chronic kidney disease, or for patients taking antidepressants.40–44 Additional sexual health resources are included in Table 6.

| Books Kaufman M, Silverberg C, Odette F. The Ultimate Guide to Sex and Disability: For All of Us Who Live with Disabilities, Chronic Pain, and Illness. 1st ed. Cleis Press; 2003. |

| Kerner I. She Comes First: The Thinking Man's Guide to Pleasuring a Woman. William Morrow Company; 2010. |

| Nagoski E. Come As You Are: The Surprising New Science That Will Transform Your Sex Life. Simon & Schuster; 2015. |

| Roche J. Queer Sex: A Trans and Non-Binary Guide to Intimacy, Pleasure and Relationships. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2018. |

| Schnarch DM. Passionate Marriage: Love, Sex, and Intimacy in Emotionally Committed Relationships. Norton; 1997. |

| Websites Advocatesforyouth.org Provides information about the community organization that partners with youth leaders, adult allies, and youth-serving organizations to advocate for policies and champion programs that recognize young people's rights to honest sexual health information; accessible, confidential, and affordable sexual health services; and the resources and opportunities necessary to create sexual health equity for all youth |

| Familydoctor.org Patient information website that includes written, video, and graphic information about a wide range of topics |

| Sexpositivefamilies.com Family-friendly website that includes patient information and resources about creating safe, shame-free spaces for comprehensive and pleasure-positive sexual health education for all ages |

This article updates a previous article on the topic by Nusbaum and Hamilton.8

Data Sources: PubMed and Cochrane library searches were completed using the terms sexual history, sexual health, sexual health history, sexual health counseling, and sexual health. Queries were also conducted matching these terms with primary care and family medicine. This search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and reviews. Guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization, and American Academy of Family Physicians were reviewed. Search dates: March 2019 and October 12, 2019.