Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(6):341-349

Related FPM article: Coding for Hypertension: Painting a Picture of the Severity of Illness

Related letter: Race-Based Treatment Decisions Perpetuate Structural Racism

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

More than 70% of adults treated for primary hypertension will eventually require at least two antihypertensive agents, either initially as combination therapy or as add-on therapy if monotherapy and lifestyle modifications do not achieve adequate blood pressure control. Four main classes of medications are used in combination therapy for the treatment of hypertension: thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). ACEIs and ARBs should not be used simultaneously. In black patients, at least one agent should be a thiazide diuretic or a calcium channel blocker. Patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction should be treated initially with a beta blocker and an ACEI or ARB (or an angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor), followed by add-on therapy with a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and a diuretic based on volume status. Treatment for patients with chronic kidney disease and proteinuria should include an ACEI or ARB plus a thiazide diuretic or a calcium channel blocker. Patients with diabetes mellitus should be treated similarly to those without diabetes unless proteinuria is present, in which case combination therapy should include an ACEI or ARB.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, and hypertension is a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease.1 Risk increases with incremental increases in blood pressure, even within the normal range.2 More than 70% of adults treated for primary hypertension will eventually require at least two antihypertensive agents.3

WHAT'S NEW ON THIS TOPIC

Hypertension Therapy

A meta-analysis showed that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors—but not angiotensin receptor blockers—reduced the incidence of doubling of the serum creatinine level in patients with diabetes mellitus, but it did not affect progression to end-stage renal disease. Another meta-analysis showed that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were superior to angiotensin receptor blockers for reducing all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Compared with monotherapy, initial combination therapy achieves blood pressure control more quickly with similar tolerability. However, in a randomized controlled trial, patients who started on monotherapy eventually achieved blood pressure control similar to that of patients who started on combination therapy.

Although improved adherence to antihypertensive medications is expected to decrease morbidity and mortality, a large systematic review found that the effects of fixed-dose combination therapy on all-cause mortality or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events are uncertain.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| For most patients, combination antihypertensive therapy should include an ACEI or ARB, a thiazide diuretic, or a calcium channel blocker.4–6 | A | Consistent evidence showing reduced morbidity and mortality with each of those four drug classes in RCTs included in guidelines |

| Patients with chronic kidney disease who have proteinuria should be prescribed an ACEI or ARB as part of combination therapy.40,41 | A | Consistent evidence from RCTs showing reduced morbidity and mortality |

| The combination of an ACEI and an ARB should be avoided.43 | B | RCT showed that benefit is outweighed by increased morbidity |

Updated hypertension guidelines were published in 2017 by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), and in 2018 by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).4,5 The American Academy of Family Physicians continues to endorse the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC8) guidelines published in 2014.6,7 For this reason, this article emphasizes JNC8 guidelines. Because patients may receive recommendations from clinicians who follow other guidelines, some key differences between these recommendations are highlighted in Table 1.4–6

| Eighth Joint National Committee, 2014 | European Society of Cardiology, 2018 | American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, 2017 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Treatment threshold (mm Hg)* | Population | Treatment threshold (mm Hg) | Treatment goal (mm Hg) | Population | Treatment threshold (mm Hg) |

| Adults 18 to 59 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | Adults 18 to 65 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 120 to 130/70 to 79 | Adults† | ≥ 130/80‡ |

| Adults 60 years and older | ≥ 150/90 | Adults 65 to 79 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||

| Adults 80 years and older | ≥ 160/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||||

| Adults with diabetes mellitus | ≥ 140/90 | Adults with diabetes, 18 to 65 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 120 to 130/70 to 79 | Adults with diabetes | ≥ 130/80 |

| Adults with diabetes, 65 to 79 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||||

| Adults with diabetes, 80 years and older | ≥ 160/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||||

| Adults with CKD | ≥ 140/90 | Adults with CKD, 18 to 65 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | Adults with CKD | ≥ 130/80 |

| Adults with CKD, 65 to 79 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||||

| Adults with CKD, 80 years and older | ≥ 160/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||||

| — | — | Adults with history of stroke, 18 to 65 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 120 to 130/70 to 79 | Adults with history of stroke§ | ≥ 130/80 |

| Adults with history of stroke, 65 to 79 years of age | ≥ 140/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||||

| Adults with history of stroke, 80 years and older | ≥ 160/90 | 130 to 139/70 to 79 | ||||

Initial management of hypertension with lifestyle changes and single-agent medications was described in detail in a previous American Family Physician article.8 This article focuses on combination therapy: when to initiate it, choice of agents, and special populations whose comorbid conditions influence those choices.

When to Initiate Combination Therapy

INADEQUATE CONTROL WITH MONOTHERAPY

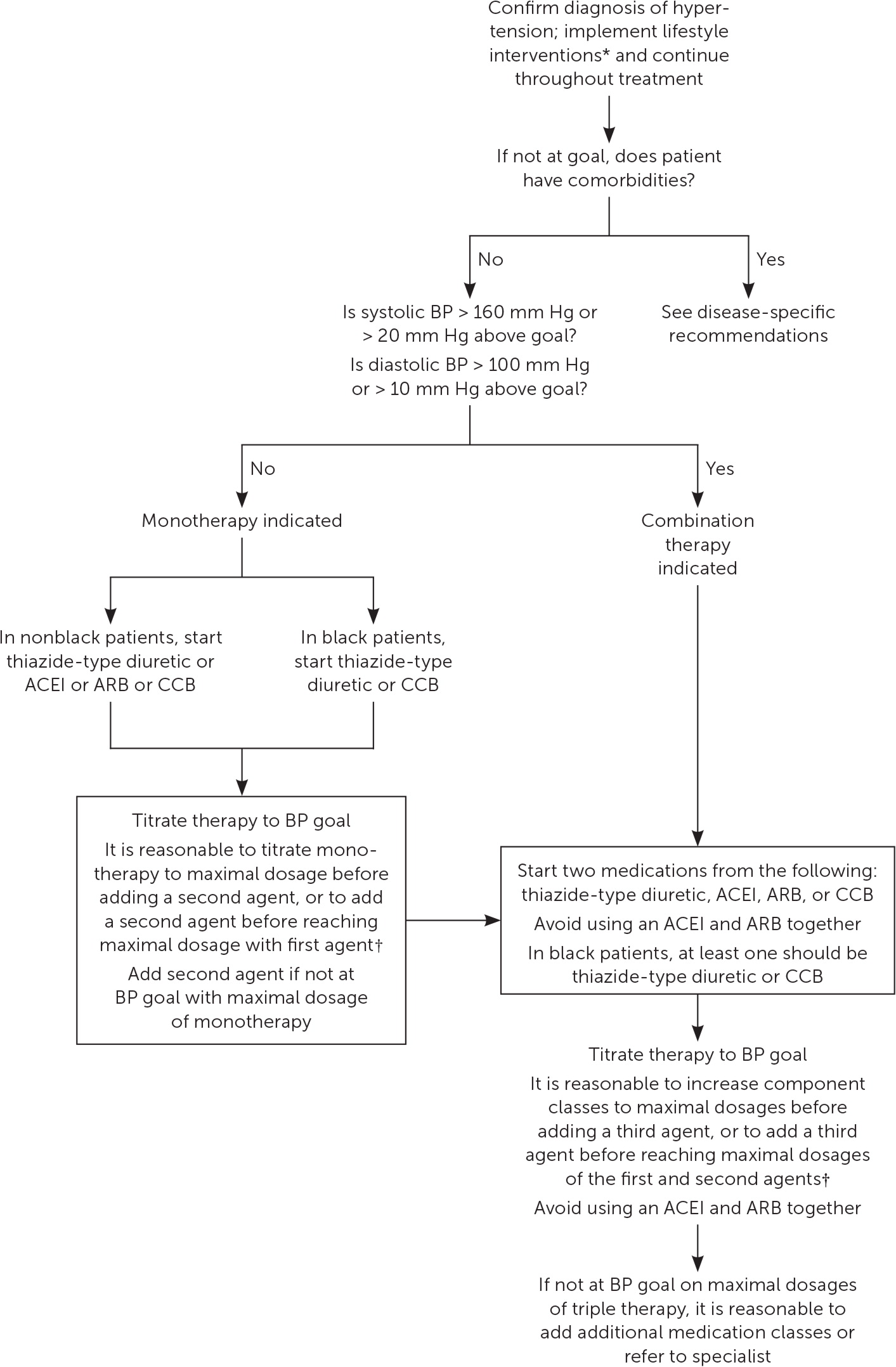

Inadequate control with monotherapy is the clearest indication for adding another medication, which can be done before or after titrating the first agent to the maximal dosage. If a patient does not achieve adequate control with a lower initial dose of a single agent, it is reasonable to titrate that medication or to add a second agent (Table 2).6 Initiating a second agent before titration of the first may result in a larger reduction in blood pressure compared with increasing the dose of the first agent.9 Response to initial monotherapy varies significantly with individual plasma renin levels, so a second mechanism of action may more appropriately address the patient's individual physiology rather than increasing the dosage of a relatively ineffective first agent.10

| Start one drug; if adequate control is not achieved in one month, titrate to maximal dosage before adding an additional agent |

| Start one drug; if adequate control is not achieved in one month, add an additional agent before titrating the initial drug to maximal dosage |

| Initiate two drugs simultaneously; if adequate control is not achieved in one month, titrate to maximal dosages before adding an additional agent, or add a third agent |

Approximately 45% of patients with hypertension and 84% of those with uncontrolled hypertension are not adherent to their antihypertensive regimen.11 Multiple studies report that combination pills containing two or three agents increase medication adherence and lower overall costs.12–14 Although improved adherence is expected to decrease morbidity and mortality, a large systematic review found that the effects of fixed-dose combination therapy on all-cause mortality or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events are unclear.15

INITIAL THERAPY

The use of combination antihypertensive agents as initial therapy has increased since 2003.16,17 Compared with monotherapy, initial combination therapy improves the average decrease in blood pressure and achieves blood pressure control faster, with similar tolerability. 9,18,19 However, patients who start on monotherapy eventually achieve similar blood pressure control as those who started on combination therapy.10

No randomized controlled trials have shown decreased cardiac risk with initial combination therapy, although some observational data have shown decreased risk.20,21 This may be because a significant number of patients are not escalated to combination therapy after titration of monotherapy as directed by guidelines, a phenomenon termed therapeutic inertia.22 Furthermore, delays of even a few months in therapy escalation are associated with an increased risk of cardiac events or death (hazard ratio = 1.1).23

Experts disagree over the lowest blood pressure that suggests the need for initial combination therapy. However, there is general agreement that initial combination therapy is safe and more effective than monotherapy in patients with systolic blood pressure higher than 160 mm Hg or greater than 20 mm Hg above goal, or with diastolic blood pressure higher than 100 mm Hg or greater than 10 mm Hg above goal.5,6,24,25 Whichever treatment strategy is chosen, escalation of therapy should occur within one month, if needed, to achieve target blood pressure.

Guidelines recommend the addition of a third agent for patients whose blood pressure is not controlled with dual therapy.6 Randomized controlled trials have shown significantly higher rates of blood pressure control in patients using a combination of an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), calcium channel blocker (CCB), and thiazide diuretic compared with those on a dual regimen of an ARB and CCB.26,27 A recent meta-analysis suggests that adding a third agent to dual therapy is more effective for lowering blood pressure than increasing dosages of dual therapy and is equally safe.28 Because of the lack of mortality data from randomized controlled trials, it is reasonable to either titrate individual agents to maximal dosages before adding an additional agent, or to add an additional agent before reaching the maximal dosage of the current agent.

Choice of Agents

Figure 1 is an algorithm that can guide combination therapy in patients with hypertension.1,6 JNC8, ESC, and ACC/AHA guidelines agree that for most patients, combination therapy should include a thiazide diuretic, a CCB, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or ARB. They further agree that a patient should not take an ACEI and ARB simultaneously.4–6 Therapy should be escalated at one-month intervals using any of the three accepted strategies (Table 2).6

The ACC/AHA recommends chlortha lidone as the preferred thiazide diuretic and recommends that central-acting alpha agonists be avoided.4 JNC8 recommends that for black patients, at least one agent should be a thiazide diuretic or CCB.6 Other drug classes may be considered for patients who do not achieve adequate blood pressure control on maximal triple therapy, or for those with comorbidities such as heart failure, diabetes mellitus, or chronic kidney disease with proteinuria (Table 3).4–6 Table 4 lists fixed-dose combination medications that are currently available.1,5

| Population | Eighth Joint National Committee, 2014 | European Society of Cardiology, 2018 | American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| General nonblack population | ACEI/ARB or CCB or thiazide diuretic | ACEI/ARB plus CCB or thiazide diuretic | ACEI/ARB or CCB or thiazide diuretic |

| General black population | ACEI/ARB* or CCB or thiazide diuretic | ACEI/ARB* or CCB or thiazide diuretic | No specific recommendation |

| Adults with diabetes mellitus | ACEI/ARB or CCB or thiazide diuretic | ACEI/ARB plus CCB or thiazide diuretic | ACEI/ARB or CCB or thiazide diuretic |

| Adults with chronic kidney disease and proteinuria (regardless of race) | ACEI/ARB plus CCB or thiazide diuretic | ACEI/ARB plus CCB or diuretic (thiazide or loop)† | ACEI/ARB plus CCB or thiazide diuretic |

| Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction | No specific recommendation | ACEI/ARB/ARNI plus beta blocker‡ plus diuretic (thiazide or loop)† | ACEI/ARB or beta blocker‡ or miner-alocorticoid receptor antagonist or thiazide diuretic |

| Combination | Medication | Dose | Cost* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI plus CCB | Amlodipine/benazepril (Lotrel) | 2.5 mg/10 mg | $14 ($215) | ||||

| 5 mg/10 mg | $16 ($290) | ||||||

| 5 mg/20 mg | $16 ($305) | ||||||

| 5 mg/40 mg | $16 (NA) | ||||||

| 10 mg/20 mg | $16 ($355) | ||||||

| 10 mg/40 mg | $16 ($390) | ||||||

| Perindopril/amlodipine (Prestalia) | 3.5 mg/2.5 mg | NA ($180) | |||||

| 7 mg/5 mg | NA ($180) | ||||||

| 14 mg/10 mg | NA ($180) | ||||||

| Trandolapril/verapamil extended release (Tarka) | 1 mg/240 mg | $65 ($185) | |||||

| 2 mg/180 mg | $47 ($185) | ||||||

| 2 mg/240 mg | $47 ($185) | ||||||

| 4 mg/420 mg | $47 ($185) | ||||||

| ACEI plus diuretic | Benazepril/HCTZ (Lotensin HCT) | 5 mg/6.25 mg | $21 (NA) | ||||

| 10 mg/12.5 mg | $24 (NA) | ||||||

| 20 mg/12.5 mg | $22 ($65) | ||||||

| 20 mg/25 mg | $22 (NA) | ||||||

| Enalapril/HCTZ (Vaseretic) | 5 mg/12.5 mg | $10 (NA) | |||||

| 10 mg/25 mg | $10 ($395) | ||||||

| Lisinopril/HCTZ (Zestoretic) | 10 mg/12.5 mg | $6 ($400) | |||||

| 20 mg/12.5 mg | $4 ($400) | ||||||

| 20 mg/25 mg | $4 ($400) | ||||||

| Quinapril/HCTZ (Accuretic) | 10 mg/12.5 mg | $17 ($150) | |||||

| 20 mg/12.5 mg | $17 ($150) | ||||||

| 20 mg/25 mg | $17 ($150) | ||||||

| ARB plus diuretic | Azilsartan/chlorthalidone (Edarbyclor) | 40 mg/12.5 mg | NA ($200) | ||||

| 40 mg/25 mg | NA ($200) | ||||||

| Candesartan/HCTZ (Atacand HCT) | 16 mg/12.5 mg | $48 ($150) | |||||

| 32 mg/12.5 mg | $50 ($155) | ||||||

| 32 mg/25 mg | $50 ($165) | ||||||

| Irbesartan/HCTZ (Avalide) | 150 mg/12.5 mg | $15 ($235) | |||||

| 300 mg/12.5 mg | $20 ($255) | ||||||

| Losartan/HCTZ (Hyzaar) | 50 mg/12.5 mg | $4 ($130) | |||||

| 100 mg/12.5 mg | $9 ($175) | ||||||

| 100 mg/25 mg | $9 ($175) | ||||||

| Olmesartan/HCTZ (Benicar HCT) | 20 mg/12.5 mg | $14 ($225) | |||||

| 40 mg/12.5 mg | $16 ($310) | ||||||

| 40 mg/25 mg | $16 ($310) | ||||||

| Telmisartan/HCTZ (Micardis HCT) | 40 mg/12.5 mg | $47 ($220) | |||||

| 80 mg/12.5 mg | $47 ($220) | ||||||

| 80 mg/25 mg | $47 ($220) | ||||||

| Valsartan/HCTZ (Diovan HCT) | 80 mg/12.5 mg | $14 ($270) | |||||

| 160 mg/12.5 mg | $9 ($295) | ||||||

| 160 mg/25 mg | $9 ($330) | ||||||

| 320 mg/12.5 mg | $17 ($370) | ||||||

| 320 mg/25 mg | $18 ($420) | ||||||

| Beta blocker plus ARB | Nebivolol/valsarten (Byvalson) | 5 mg/80 mg | NA ($130) | ||||

| Beta blocker plus diuretic | Atenolol/chlorthalidone (Tenoretic) | 50 mg/25 mg | $15 ($360) | ||||

| 100 mg/25 mg | $19 ($155) | ||||||

| Bisoprolol/HCTZ (Ziac) | 2.5 mg/6.25 mg | $9 ($200) | |||||

| 5 mg/6.25 mg | $13 ($200) | ||||||

| 10 mg/6.25 mg | $12 ($200) | ||||||

| Metoprolol/HCTZ (Lopressor HCT) | 50 mg/25 mg | $20 ($70) | |||||

| 100 mg/25 mg | $25 (NA) | ||||||

| 100 mg/50 mg | $29 (NA) | ||||||

| Nadolol/bendroflumethiazide (Corzide) | 40 mg/5 mg | $64 ($245) | |||||

| 80 mg/5 mg | $78 ($320) | ||||||

| CCB plus ARB | Amlodipine/olmesartan (Azor) | 5 mg/20 mg | $23 ($280) | ||||

| 5 mg/40 mg | $28 ($350) | ||||||

| 10 mg/20 mg | $28 ($280) | ||||||

| 10 mg/40 mg | $28 ($350) | ||||||

| Amlodipine/valsartan (Exforge) | 5 mg/160 mg | $20 ($270) | |||||

| 5 mg/320 mg | $25 ($340) | ||||||

| 10 mg/160 mg | $20 ($305) | ||||||

| 10 mg/320 mg | $25 ($385) | ||||||

| Telmisartan/amlodipine (Twynsta) | 40 mg/5 mg | $50 (NA) | |||||

| 40 mg/10 mg | $50 (NA) | ||||||

| 80 mg/5 mg | $50 ($240) | ||||||

| 80 mg/10 mg | $55 ($240) | ||||||

| CCB plus diuretic plus ARB | Amlodipine/valsartan/HCTZ (Exforge HCT) | 5 mg/160 mg/12.5 mg | $43 ($270) | ||||

| 5 mg/160 mg/25 mg | $46 ($270) | ||||||

| 10 mg/160 mg/12.5 mg | $53 ($305) | ||||||

| 10 mg/160 mg/25 mg | $55 ($305) | ||||||

| 10 mg/320 mg/25 mg | $55 ($390) | ||||||

| Olmesartan/amlodipine/HCTZ (Tribenzor) | 20 mg/5 mg/12.5 mg | $58 ($280) | |||||

| 40 mg/5 mg/12.5 mg | $55 ($350) | ||||||

| 40 mg/5 mg/25 mg | $57 ($350) | ||||||

| 40 mg/10 mg/12.5 mg | $65 ($350) | ||||||

| 40 mg/10 mg/25 mg | $60 ($350) | ||||||

| Diuretic plus diuretic | Spironolactone/HCTZ (Aldactazide) | 25 mg/25 mg | $17 ($85) | ||||

| 50 mg/50 mg | NA ($150) | ||||||

| Triamterene/HCTZ (Maxzide) | 37.5 mg/25 mg | $4 ($55) | |||||

| 75 mg/50 mg | $4 ($115) | ||||||

| Renin inhibitor plus diuretic | Aliskiren/HCTZ (Tekturna HCT) | 150 mg/12.5 mg | NA ($215) | ||||

| 150 mg/25 mg | NA ($215) | ||||||

| 300 mg/12.5 mg | NA ($270) | ||||||

| 300 mg/25 mg | NA ($270) | ||||||

Special Populations

These general antihypertensive therapy recommendations complement treatment recommendations for each disease state. In some cases, antihypertensive medications may be used to treat the underlying disease regardless of blood pressure. For this reason, these recommendations should be used in conjunction with disease-specific guidelines.

HEART FAILURE

ACEIs are associated with decreased cardiovascular mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).29 A Cochrane review showed that ARBs are no better than ACEIs or placebo in reducing morbidity or mortality in patients with HFrEF,30 but they are a reasonable alternative for patients who cannot tolerate ACEIs. The Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial showed that angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with HFrEF compared with ACEIs and may be a second-line alternative to ACEIs or ARBs.31 The JNC8 found insufficient evidence to recommend preferential use of ACEIs or ARBs in patients with heart failure and hypertension6; however, the JNC8 recommendations were published before the PARADIGM-HF results.

The beta blockers carvedilol (Coreg), extended-release metoprolol (Toprol XL), and bisoprolol (Zebeta) have shown improvements in morbidity and mortality. One of these agents should be initiated in patients with HFrEF unless they have contraindications.32–34 Beta blockers are usually added once the patient no longer has symptoms of volume overload.

CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE

Long-term follow-up of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) trial and the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) trial showed that improved blood pressure control decreases mortality.37,38 A 2017 meta-analysis of patients with stage 3 to 5 chronic kidney disease found a decreased risk of all-cause mortality in patients who received more intensive blood pressure control compared with less intensive control (systolic blood pressure decrease of 16 vs. 8 mm Hg, respectively).39

ACEIs and ARBs reduce proteinuria and decrease progression to end-stage renal disease in patients with proteinuria.40,41 The MDRD and AASK studies did not find benefit in patients without proteinuria, and a systematic review suggests that improved renal outcomes associated with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone blockade may be entirely due to their blood pressure–lowering effect.42 The combination of an ACEI and ARB is not recommended because of the increased risk of end-stage renal disease and lack of mortality benefit.41,43 The JNC8 recommends that patients with chronic kidney disease be treated with an ACEI or an ARB, in addition to a thiazide diuretic or a CCB.6 A loop diuretic may be considered if the estimated glomerular filtration rate is less than 30 mL per minute per 1.73 m2, based on low-quality evidence that thiazide diuretics have decreased effectiveness in people with reduced renal function.5,44

Direct renin inhibitors (e.g., aliskiren [Tekturna]) were not considered by the JNC8 because there were no studies showing their benefits on kidney or cardiovascular outcomes. The ESC notes that aliskiren combined with an ACEI or ARB led to adverse events in patients with diabetes.5 Although newer direct renin inhibitors are being developed, they are not yet widely used.

DIABETES

Using a fixed-dose combination of an ACEI and a thiazide diuretic in adults with diabetes, the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial showed that a blood pressure decrease of 5.6/2.2 mm Hg led to lower rates of microvascular and macrovascular events and of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.45

ACEIs or ARBs should be used in patients with proteinuria, including those with diabetes. In patients with diabetes who do not have proteinuria, there is no benefit in using an ACEI or ARB compared with a CCB or thiazide diuretic.5,6 A meta-analysis showed that ACEIs—but not ARBs— reduce the incidence of doubling of the serum creatinine level in patients with diabetes, but they do not affect progression to end-stage renal disease.46 Another meta-analysis showed that ACEIs are superior to ARBs in reducing all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.47 The ACCOMPLISH trial showed that patients with diabetes who are treated with a combined ACEI/CCB have a lower risk of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events compared with those treated with a combined ACEI/thiazide diuretic.48

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Frank,49 and by Skolnik, et al.50

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms hypertension, hypertension treatment, and hypertension combination therapy. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. We also searched the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. In addition, references in these resources were searched. Search dates: March to September 2019.

The contents of this article are solely the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. military at large, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Editor's Note: As we continue to navigate the complexities of managing chronic disease in our patients, we must remember that many conditions, including hypertension, are affected by environmental, behavioral, and sociocultural factors as opposed to genetics alone. While guidelines from the US and other countries continue to use race as a surrogate in determining pharmacotherapy, it is critical for us to determine the true underlying cause for differences in morbidity/mortality and differences in response to therapies rather than assuming it is based on one’s skin tone or identifying as Black.A1 For example, the variability in response to ACEI monotherapy is greater within races than it is between races.A2,A3 And ACEIs remain an important therapy for chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and hypertension requiring multiple drugs irrespective of race.A3

As we interpret guidelines and make decisions on therapy, we must continue to discuss the current limitations of the evidence with our patients. In addition, we need to challenge ourselves and our organizations to encourage researchers and guideline developers to reach beyond our traditional use of race as a “risk factor”. An individual’s race is an unmitigable social construct. Using race as a proxy limits our ability to identify and address the actual, likely multifactorial, and possibly mitigable qualities of concern. These areas are where we need to focus our research efforts.—Sumi Sexton, MD, Editor-in-Chief, and Renee Crichlow, MD, Medical Editor for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

A1. Williams SK, Ravenell J, Seyedali S, et al. Hypertension treatment in Blacks: discussion of the U.S. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;59(3):282-288.

A2. Sehgal AR. Overlap between whites and blacks in response to antihypertensive drugs. Hypertension. 2004 Mar;43(3):566-572.

A3. Peck RN, Smart LR, Beier R, et al. Difference in blood pressure response to ACE-Inhibitor monotherapy between black and white adults with arterial hypertension: a meta-analysis of 13 clinical trials. BMC Nephrol. 2013;26(14):201.