Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(5):291-296

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Esophageal motility disorders can cause chest pain, heartburn, or dysphagia. They are diagnosed based on specific patterns seen on esophageal manometry, ranging from the complete absence of contractility in patients with achalasia to unusually forceful or disordered contractions in those with hypercontractile motility disorders. Achalasia has objective diagnostic criteria, and effective treatments are available. Timely diagnosis results in better outcomes. Recent research suggests that hypercontractile motility disorders may be overdiagnosed, leading to unnecessary and irreversible interventions. Many symptoms ascribed to these disorders are actually due to unrecognized functional esophageal disorders. Hypercontractile motility disorders and functional esophageal disorders are generally self-limited, and there is considerable overlap among their clinical features. Endoscopy is warranted in all patients with dysphagia, but testing to evaluate for less common conditions should be deferred until common conditions have been optimally managed. Opioid-induced esophageal dysmotility is increasingly prevalent and can mimic symptoms of other motility disorders or even early achalasia. Dysphagia of liquids in a patient with normal esophagogastroduodenoscopy findings may suggest achalasia, but high-resolution esophageal manometry is required to confirm the diagnosis. Surgery and advanced endoscopic therapies have proven benefit in achalasia. However, invasive interventions are rarely indicated for hypercontractile motility disorders, which are typically benign and usually respond to lifestyle modifications, although pharmacotherapy may occasionally be needed. (Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(5):291–296. Copyright © 2020 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

Esophageal motility disorders are relatively uncommon conditions that are thought to cause chest pain or dysphagia in some patients. They are diagnosed not by specific symptoms or imaging studies, but on the basis of specific patterns seen on esophageal manometry, ranging from the complete absence of contractility in patients with achalasia to unusually forceful or disordered contractions in those with hypercontractile motility or “esophageal spasm” disorders.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians should ensure optimal evaluation and management of common conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional esophageal disorders before referring patients for testing for esophageal motility disorders.1,4–7 | C | Consensus guideline and expert opinion |

| Patients with dysphagia should be asked about opioid use and helped to discontinue or taper the medication.7 | C | Disease-oriented retrospective review |

| High-resolution manometry is required to confirm the diagnosis of achalasia.17 | C | Clinical guideline |

| Esophageal motility disorders usually respond to lifestyle modifications, although pharmacotherapy may occasionally be needed.6,25 | B | Case series and longitudinal cohort study |

| Patients with achalasia should undergo definitive therapy when possible.28 | C | Expert opinion and guideline |

| Invasive procedures are rarely needed for patients with hypercontractile motility disorders.2 | B | Small randomized controlled trial |

Achalasia has well-defined and objective diagnostic criteria, as well as effective evidence-based treatment options, but its diagnosis is often delayed. Conversely, recent research suggests that hypercontractile motility disorders may be overdiagnosed,2 leading to unnecessary and irreversible interventions. Although gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and unrecognized functional esophageal disorders are more likely than achalasia or hypercontractile motility disorders to cause chronic symptoms,3,4 family physicians should also be familiar with the current understanding and terminology of these less common conditions to ensure timely and appropriate referral for testing and intervention.

Classification and Epidemiology

When normal swallowing (deglutition) is initiated, the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes, followed within one to two seconds by the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing a food bolus from the oropharynx to be propelled by peristalsis through the esophagus and into the stomach. In normal peristalsis, excitatory neurons cause contraction of one segment of smooth muscle as inhibitory neurons relax the segment below.

Achalasia is the esophageal motility disorder of greatest clinical significance. Hypercontractile motility disorders, although seemingly well-defined, may overlap with functional esophageal disorders to a greater degree than previously recognized. Several other conditions are classified among the esophageal motility disorders but are much less relevant (Table 1).1,4–7

| Disorder | Lower esophageal sphincter tone | Peristalsis | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achalasia | |||

| Type I (classic) | Fails to relax | 100% failed (no contractility) | Responds to laparoscopic Heller myotomy, less so to pneumatic dilation |

| Type II (with esophageal compression) | Fails to relax | Some pressurization, but no normal peristalsis | All treatments are effective |

| Type III (spastic) | Fails to relax | No normal peristalsis and spastic contractions distally in more than 20% of swallows | Poor response to treatment |

| Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction | Fails to relax | Some preserved | May reflect a physical obstruction at the level of the lower esophageal sphincter rather than early achalasia |

| Major disorders of peristalsis* | |||

| Absent contractility | Normal | Failed | Relatively rare; easily diagnosed but treatments are only minimally effective; common in patients with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma); included among the major motility disorders but typically manifests with reflux, not dysphagia or chest pain1 |

| Distal esophageal spasm | Normal | Premature distal contraction with poor peristalsis | Relatively rare; diagnosis is difficult and treatments are only minimally effective |

| Hypercontractile (jackhammer) esophagus | Normal | Abnormally forceful contractions | Relatively rare; diagnosis is difficult and treatments are only minimally effective |

| Minor disorders of peristalsis† | |||

| Fragmented peristalsis | Normal | > 50% fragmented contractions | — |

| Ineffective esophageal motility | Normal | > 50% ineffective swallows | — |

ACHALASIA

Achalasia is a progressive disorder that may not be recognized in its early stages, but that causes increasingly troublesome dysphagia and chest pain over time.8 It is present in less than 5% of patients referred to specialized centers.9 Achalasia can occur at any age but is more common in older adults. In this degenerative disorder, chronic esophageal smooth muscle denervation causes a deficiency of nitric oxide in tissues and a progressive loss of inhibitory neurons, ultimately resulting in impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and absence of normal peristalsis. Although delayed diagnosis of achalasia does not increase the risk of esophageal cancer,10 it can cause significant esophageal dilatation over time, which may make surgical treatment less successful.11

HYPERCONTRACTILE MOTILITY DISORDERS

Distal esophageal spasm and hypercontractile (jackhammer) esophagus are the major hypercontractile motility disorders. These disorders are rare, even in referral populations, and occur primarily in people 60 years and older.5,6 They are also thought to result from the loss of inhibitory neuronal function. Distal esophageal spasm is characterized by premature contractions that are more forceful than normal. Jackhammer esophagus is characterized by appropriately timed but abnormally forceful hypercontractile peristalsis. Some patients with early achalasia have abnormal contractions similar to those occurring in distal esophageal spasm or jackhammer esophagus; however, these disorders themselves rarely progress to achalasia.12

Although the general term “esophageal spasm” is often used to refer to chest pain or dysphagia not explained by other causes, it should be used only in the context of hypercontractile motility disorders.

FUNCTIONAL ESOPHAGEAL DISORDERS

Like irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia, functional esophageal disorders involve abnorma lities of gut–brain interaction and central nervous system processing.4,13 Patients may report chest pain, heartburn, or dysphagia, and they may be hypervigilant about minor symptoms or hypersensitive to even physiologic amounts of acid. These disorders usually have a benign and self-limited course.

Although patients with functional esophageal disorders may have hypercontractile patterns on manometry, this may not be the cause of their symptoms. In a recent trial, patients who met criteria for hypercontractile motility disorders were randomized to onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injection or a sham injection procedure.2 After three months, symptoms and manometric abnormalities were significantly and equally improved in both groups, suggesting that many symptoms ascribed to hypercontractility are actually due to unrecognized functional esophageal disorders.14

Clinical Features

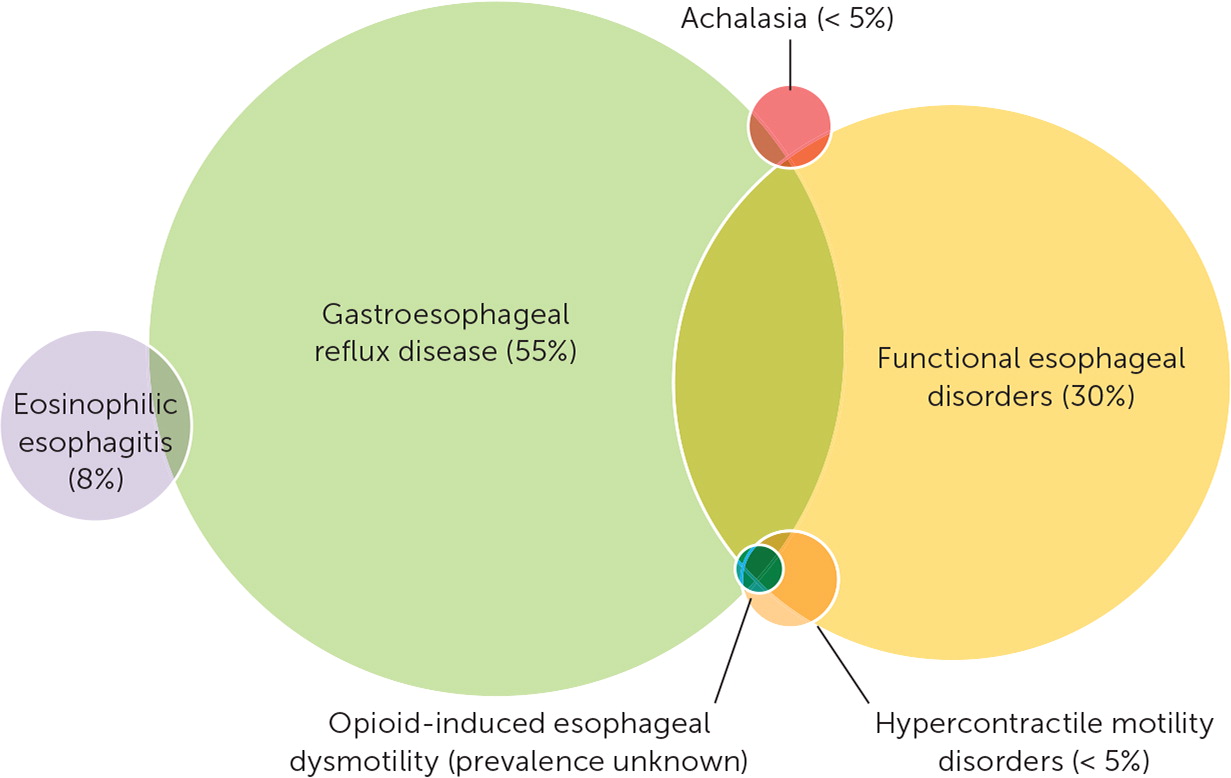

Although specific symptoms may suggest an etiology, the physiologic responses of the esophagus are limited, and there is considerable overlap among the clinical features of esophageal disorders (Figure 1).5,9,11,15 In addition, many patients have coexisting GERD or functional esophageal disorders, or both.

DYSPHAGIA

Patients with esophageal dysfunction and impaired peristalsis often report a sensation of food getting stuck in the throat, neck, or chest. However, the actual level of the food bolus may not correlate with its perceived location because of overlapping sensory innervation. For example, if a patient describes food getting stuck at the level of the neck, it could actually be at the lower esophageal sphincter.16

Patients with achalasia may report straightening the chest or even standing up and walking around during a meal in an attempt to improve swallowing. They may regurgitate food several hours after a meal, often while sleeping.

Patients who have difficulty swallowing liquids as well as solids are more likely to have a motility disorder than those who have dysphagia with only solids. The dysphagia may be related to specific foods, particularly cold liquids. Anxiety or stress, alcohol intake, and eating too rapidly also may provoke dysphagia.17 Patients who have difficulty initiating swallowing or who experience choking or nasopharyngeal regurgitation are more likely to have an oropharyngeal disorder than an esophageal disorder. Opioid-induced esophageal dysmotility is increasingly prevalent and can produce symptoms and a contraction pattern indistinguishable from other motility disorders or even early achalasia.7

CHEST PAIN

Excessively forceful esophageal contractions occasionally provoke chest pain.18 Hence, chest pain that occurs during meals may suggest a hypercontractile motility disorder. Chest pain unrelated to meals or that occurs in the absence of dysphagia (often reported as sudden and lasting for minutes to hours) is more likely related to GERD or functional esophageal disorders.

Testing

Testing for esophageal motility disorders should be done judiciously to avoid overdiagnosis. Many patients with recurrent symptoms will have already undergone endoscopy and tried acid-suppressing medications. Family physicians should ensure that common conditions have been optimally managed before considering referral for testing for less common conditions(Table 2).1,4–7 Additional information is available in previous American Family Physician articles.19–23

| Esophageal motility disorders Achalasia or esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction Major disorder of peristalsis (distal esophageal spasm, hypercontractile [jackhammer] esophagus, absent contractility) Minor disorder of peristalsis |

| GERD and esophagitis GERD (nonerosive) Eosinophilic esophagitis |

| Functional esophageal disorders Acid hypersensitivity Functional dysphagia (sensation of abnormal food bolus transit through the esophagus in the absence of structural, mucosal, or motor abnormalities) Functional heartburn |

| Infection Infectious esophagitis (due to cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, or Candida infection) |

| Structural or mechanical causes Dysphagia lusoria (aberrant right subclavian artery) or other vascular ring abnormality (e.g., enlarged left atrium or aorta) Esophageal stricture (due to erosive esophagitis) Foreign body Malignancy (esophageal, gastric, or mediastinal) Schatzki ring |

| Other Medication adverse effect (e.g., decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone from nitrates, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, opioids, calcium channel blockers, or tricyclic antidepressants) Pill esophagitis (direct irritation of esophagus, commonly caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bisphosphonates, tetracyclines, potassium chloride, quinidine, ferrous sulfate, or ascorbic acid) |

MANAGEMENT OF COMMON CONDITIONS

Acid-suppressing therapy should be optimized for patients with GERD or persistent symptoms that suggest GERD, even if acid reflux cannot be demonstrated.3 Patients whose symptoms are not responsive to acid-suppressing therapy likely have one of the functional esophageal disorders, which are almost as common as GERD but less often considered.15 Treatments that focus on modulating esophageal visceral hypersensitivity and hypervigilance, such as antidepressants, are somewhat effective in reducing symptoms in these patients.4,24

All patients who have dysphagia should be asked about opioid use. Opioids should be discontinued before testing for achalasia or other esophageal motility disorders.7

ESOPHAGOGASTRODUODENOSCOPY

All patients with dysphagia should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to rule out malignancy and other structural lesions, as well as eosinophilic esophagitis, infections, and inflammatory conditions. Retained food in the esophagus and abnormal resistance across the esophagogastric junction strongly suggest achalasia, but manometry is required to confirm the diagnosis.17

BARIUM ESOPHAGOGRAPHY

HIGH-RESOLUTION ESOPHAGEAL MANOMETRY

High-resolution esophageal manometry uses closely spaced pressure sensors affixed to a nasogastric catheter to measure esophageal pressure changes during multiple swallows of standardized foods and liquids. Esophageal motility disorders are classified on the basis of specific contraction and relaxation pressures recorded along the esophageal body during peristalsis and at the lower esophageal sphincter before swallowing and during relaxation (Table 1).1,4–7 Manometry is indicated in patients who continue to have dysphagia and chest pain despite optimal medical management, especially those who have normal EGD findings and persistent dysphagia to liquids. Because of its low predictive value, manometry is generally not recommended for patients who have chest pain without dysphagia. Manometry is required to confirm the diagnosis of achalasia.17

Management

Patients with functional esophageal disorders have excellent long-term outcomes: approximately 50% have complete resolution of symptoms, and another 30% improve to some degree over time.25 Patients with hypercontractile motility disorders have similarly favorable long-term outcomes, perhaps because many of them actually have unrecognized functional disorders.2 Therefore, treatment for these disorders—even in patients with positive manometry findings—is often unnecessary or ineffective, and perhaps even harmful. Family physicians should address the patient's concerns, especially about heart disease and cancer, and reassure them that most esophageal motility disorders are benign and self-limited.

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS

Hypercontractile esophageal motility disorders usually respond to lifestyle modifications, although pharmacotherapy may occasionally be needed.6,25 Patients with esophageal symptoms from any cause—even achalasia—typically benefit from eating mindfully; eating smaller, softer, and more frequent meals; and avoiding trigger foods or situations. Dysmotility related to opioid use is potentially reversible with discontinuation or tapering.7 Cognitive behavior therapy, hypnosis, and other complementary treatments have had some success in the management of functional disorders, but further research is needed.4

MEDICATIONS

Medical therapy is not effective for the treatment of achalasia but may be helpful for hypercontractile motility disorders. Calcium channel blockers and nitrates, which relax smooth muscle, and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, which release nitric oxide, are sometimes used. Because these medications can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and worsen GERD, they should not be used empirically, but only after esophageal hypercontractility has been confirmed by manometry.26

Peppermint oil (two mints taken sublingually before each meal) is safe and inexpensive, and there is limited evidence that it can decrease esophageal contractions.27

ENDOSCOPIC AND SURGICAL THERAPIES

Laparoscopic Heller myotomy, in which muscle fibers of the distal esophagus, lower esophageal sphincter, and gastric cardia are incised, is the definitive treatment for achalasia. Peroral endoscopic myotomy is a newer option in which the same muscle fibers are incised using a less invasive but technically more difficult endoscopic approach. Although this procedure may become more widely used in the future, its current role is not clear.28 It has been used to treat hypercontractile motility disorders, but no prospective randomized studies have evaluated its effectiveness.

Pneumatic dilation uses an endoscopically guided balloon to disrupt the lower esophageal sphincter. Although this procedure is effective for achalasia, results are not as durable as with Heller myotomy, and it may need to be repeated.

OnabotulinumtoxinA has been endoscopically injected into the lower esophageal sphincter to treat achalasia in patients who are too frail for definitive surgical therapy. However, a small randomized controlled trial found that this approach did not have significant benefit in patients with hypercontractile esophageal motility disorders.2

Data Sources: We searched PubMed and Google Scholar using the following search terms alone and in combination: esophageal spasm, achalasia, nutcracker esophagus, jackhammer esophagus, and esophageal motility disorder. We examined clinical trials, meta-analyses, review articles, and clinical guidelines, as well as the bibliographies of selected articles. The Cochrane database and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: March 2019 to April 2020.