Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(3):277-287

Related editorial: Parasitic Infections: Do Not Neglect Strongyloidiasis

Related letter: Treatment of Chagas Disease in Breastfeeding Dyads

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Chagas disease, cysticercosis, and toxoplasmosis affect millions of people in the United States and are considered neglected parasitic diseases. Few resources are devoted to their surveillance, prevention, and treatment. Chagas disease, transmitted by kissing bugs, primarily affects people who have lived in Mexico, Central America, and South America, and it can cause heart disease and death if not treated. Chagas disease is diagnosed by detecting the parasite in blood or by serology, depending on the phase of disease. Antiparasitic treatment is indicated for most patients with acute disease. Treatment for chronic disease is recommended for people younger than 18 years and generally recommended for adults younger than 50 years. Treatment decisions should be individualized for all other patients. Cysticercosis can manifest in muscles, the eyes, and most critically in the brain (neurocysticercosis). Neurocysticercosis accounts for 2.1% of all emergency department visits for seizures in the United States. Diagnosing neurocysticercosis involves serology and neuroimaging. Treatment includes symptom control and antiparasitic therapy. Toxoplasmosis is estimated to affect 11% of people older than six years in the United States. It can be acquired by ingesting food or water that has been contaminated by cat feces; it can also be acquired by eating undercooked, contaminated meat. Toxoplasma infection is usually asymptomatic; however, people who are immunosuppressed can develop more severe neurologic symptoms. Congenital infection can result in miscarriage or adverse fetal effects. Diagnosis is made with serologic testing, polymerase chain reaction testing, or parasite detection in tissue or fluid specimens. Treatment is recommended for people who are immunosuppressed, pregnant patients with recently acquired infection, and people who are immunocompetent with visceral disease or severe symptoms.

Neglected parasitic infections designated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) include Chagas disease, cysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, and trichomoniasis.1 These parasitic infections have been prioritized based on the number of people infected, the potential for severe illness, and availability of treatment regimens. This article reviews three infections that are typically not emphasized in medical training—Chagas disease, cysticercosis, and toxoplasmosis. Information on the others (toxocariasis and trichomoniasis) can be found on the CDC website.1 Despite the ability to cause severe illness, limited resources have been devoted to understanding the impact and burden of neglected parasitic infections. Family physicians should understand the basic principles of clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of these diseases. A summary of key points for each disease is presented in Table 1.2

| Disease | Epidemiology and transmission | Clinical manifestations | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chagas disease | More than 300,000 people in the United States are infected; more common in people who have lived in Mexico and Central or South America; locally acquired infection is rare Transmission is often vectorborne (kissing bugs), less commonly congenital, or via blood transfusion or organ transplant Blood donations are screened; blood donors who test positive cannot donate again | Acute infection: usually asymptomatic; when symptoms occur, they typically appear four to eight weeks after infection; and include nonspecific febrile illness and swelling around the bite site Chronic infection: 20% to 30% of people develop symptoms, including cardiac and gastrointestinal manifestations; increased risk of stroke Congenital infection: usually asymptomatic; anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, low Apgar scores, low birth weight, thrombocytopenia; rarely, meningoencephalitis, myocarditis | Acute and congenital infections: direct microscopy of peripheral or cord blood to detect parasites; polymerase chain reaction testing also available Chronic infection: no or few parasites in the blood; multiple serologic tests with varying sensitivity and specificity are available; at least two positive results on different serologic tests required for diagnosis | Infection is lifelong without treatment; people with acute or congenital infection and people who are immunocompromised with reactivated infection should be treated; people with severe renal or hepatic insufficiency should not be treated; patients should not be treated during pregnancy but should be evaluated for treatment after delivery; for chronic disease, treatment is strongly recommended in people younger than 18 years and generally recommended in people younger than 50 years who do not have severe cardiomyopathy; all others should be treated on an individual basis Treatment options include nifurtimox (Lampit) or benznidazole |

| Cysticercosis | More common in immigrants from Central and South America, but can occur in people from other endemic areas and in people born in the United States Transmission occurs by ingesting eggs excreted in the feces of a tapeworm carrier; transmission does not occur by eating under-cooked infected pork | Neurocysticercosis: may be asymptomatic; seizures are the most common manifestation; chronic meningitis, cranial nerve abnormalities, headache, and intracranial hypertension or hydrocephalus may also occur Muscular cysticerci are usually asymptomatic | Neurocysticercosis: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are recommended; confirmatory serologic test recommended; number, location, and viability of cysticerci should be determined | Neurocysticercosis: symptom control is the priority; decision to treat with antiparasitic drugs should be individualized; coadministration of corticosteroids may decrease inflammatory response People with cysticercosis and close contacts should be screened for tapeworm infection |

| Toxoplasmosis | Approximately 11% of people in the United States are infected; symptomatic infection is more common in people who are immunocompromised and in children with congenital infection Transmission is most often food-borne, zoonotic from cat feces, or congenital | Most people who are immunocompetent are symptomatic; people who are immunosuppressed may develop encephalitis with confusion, fever, headache, poor coordination, or seizures; patients infected during pregnancy may have a miscarriage or a child born with signs of toxoplasmosis; ocular symptoms may include eye pain, blurred vision, or photophobia | Toxoplasma antibody test (specialized testing may be required to determine if the infection is acute or chronic); serologic tests may be unreliable in patients who are immunosuppressed; microscopy to detect parasite in blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or tissue; polymerase chain reaction testing also available | Spiramycin should be used before amniocentesis to assess fetal infection in pregnant patients who acquire the infection in the first or early second trimester; can also be used later in pregnancy if it has been demonstrated that the fetus is not infected Combination therapy with pyrimethamine (Daraprim), sulfadiazine, and leucovorin should be used in infants with congenital infection, in pregnant patients who acquire infection in the late second or third trimester or who acquire the infection earlier and transmit it to the fetus, in patients who are immunosuppressed, and in patients who are immunocompetent with severe symptoms |

Chagas Disease

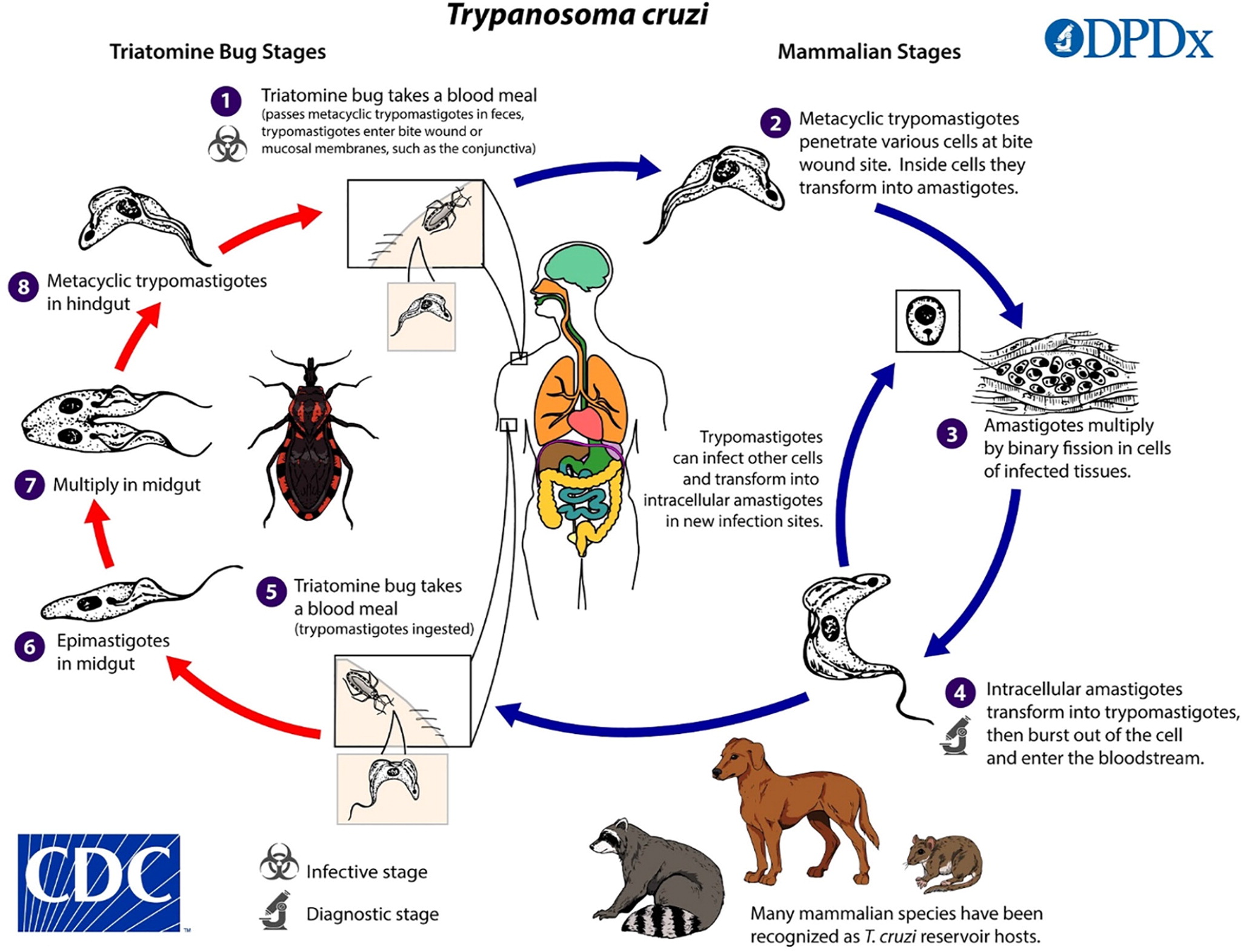

Chagas disease (i.e., American trypanosomiasis) is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Transmission to humans occurs mainly through contact with triatomine insects (kissing bugs), bloodsucking insects that feed on humans and other animals. Infection occurs when an infected triatomine insect defecates after a blood meal, and the feces containing the parasite are rubbed into a bite wound or mucous membranes (Figure 1).3 Transmission can also occur congenitally or by blood transfusion, organ transplant, consumption of food contaminated with triatomine-infected feces, or laboratory exposure.

Chagas disease is endemic in many parts of Mexico and Central and South America, where an estimated 7 million people are infected.4 More than 300,000 people in the United States are thought to be infected, most of whom acquired the disease in Latin America.4 However, infected triatomines have been found in many parts of the southern United States, and domestic transmission via triatomines has occurred.5

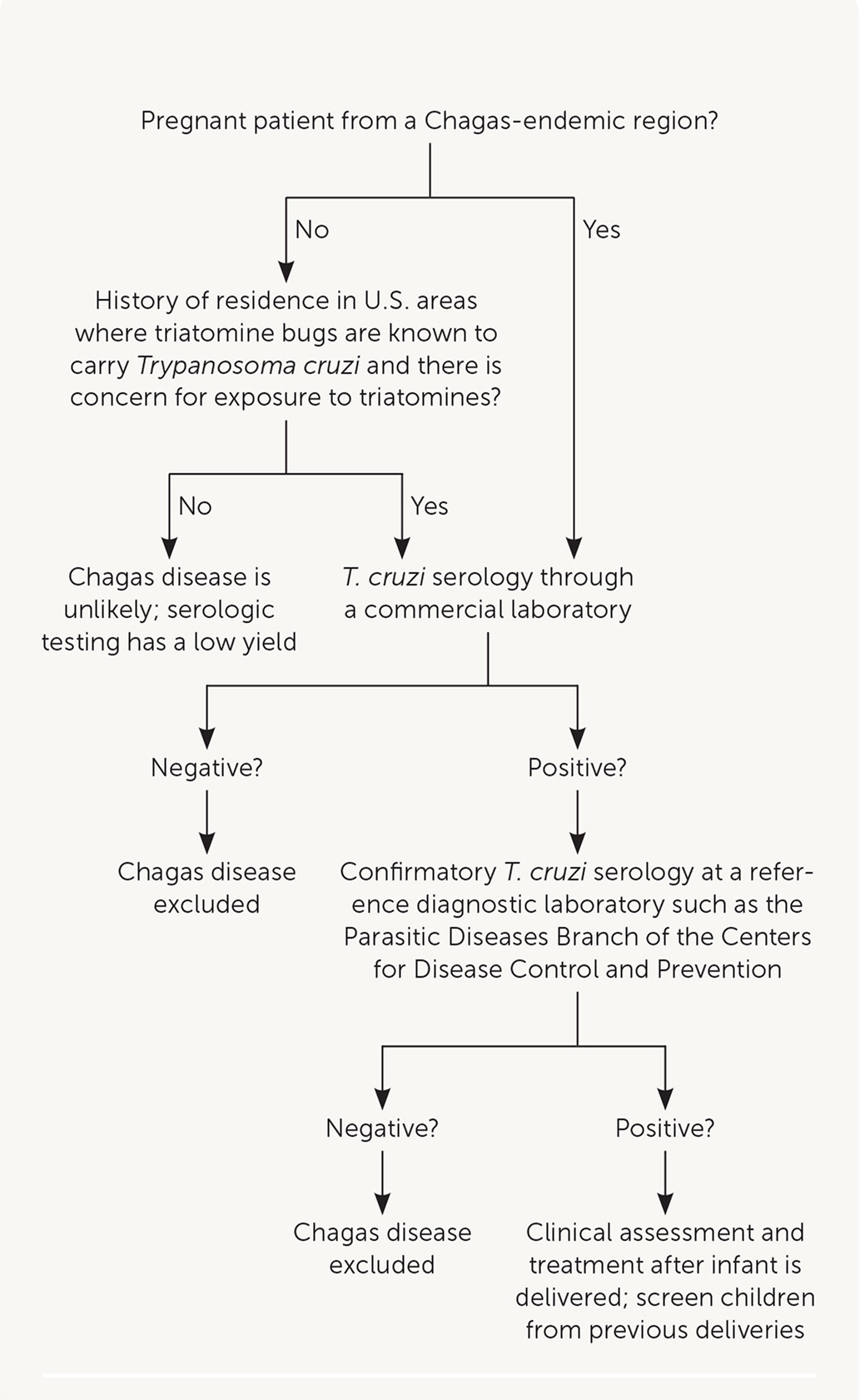

In the United States, it is estimated that up to 300 infants are congenitally infected with T. cruzi each year.4 Screening pregnant patients for Chagas disease is not routinely performed, but targeted testing based on their risk history is recommended (Figure 2). Blood donor screening in the United States was implemented in 2007, making the U.S. blood supply safe from the risk of transfusion-transmitted infection.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The acute phase lasts for weeks or months after the initial infection, and the chronic phase is lifelong in the absence of treatment. In the acute phase, clinical manifestations are often mild or absent; however, patients may have swelling around the bite site. If the inoculation site is the conjunctiva, unilateral palpebral edema may occur. In the chronic phase, most patients are asymptomatic, but 20% to 30% develop clinical manifestations that can be life-threatening.6 Cardiac disease, including conduction abnormalities, dilated cardiomyopathy, apical aneurysm, or heart failure, may occur. The risk of stroke is also increased. Gastrointestinal manifestations include megaesophagus or megacolon.

Most congenitally infected infants are asymptomatic; however, some may have low birth weight, low Apgar scores, or develop anemia, thrombocytopenia, or hepatosplenomegaly. Rarely, myocarditis or meningoencephalitis may occur.

DIAGNOSIS

Acute or congenital Chagas disease can be diagnosed by detecting parasites via direct microscopy of anticoagulated peripheral or cord blood. Polymerase chain reaction testing for T. cruzi DNA in blood may be used in addition to microscopy.

In the chronic phase, few or no parasites are present on microscopy; therefore, serologic testing for antibodies to T. cruzi is required for diagnosis. Positive results on at least two different tests are required for diagnosis because no single serologic test has sufficient sensitivity and specificity.

Patients who have lived in Mexico, Central America, or South America are at risk of chronic Chagas disease and should be tested. Because of the risk of congenital transmission and potentially shared exposure history, children born to mothers with Chagas disease should also be tested.4,7 Blood donors in the United States who have positive results on screening for T. cruzi infection cannot donate blood and are advised to consult with their physician for diagnostic workup and confirmation of infection.

Patients with newly diagnosed Chagas disease should have a physical examination to screen for end-organ involvement. Electrocardiography is important because arrhythmias are an early manifestation of Chagas heart disease and may be asymptomatic.

TREATMENT

Immediate antiparasitic treatment with benznidazole or nifurtimox (Lampit) is indicated for patients with acute disease, congenital infection, and for patients who are immunocompromised with reactivated disease.8 In chronic Chagas disease, treatment is strongly recommended for patients younger than 18 years and generally recommended for adults younger than 50 years who do not have advanced cardiomyopathy. For patients 50 years and older, treatment decisions should be individualized because most older patients have been infected for decades and treatment has a low chance of a cure.4,8

Benznidazole is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat children two to 12 years of age. Nifurtimox is FDA-approved to treat children from birth up to 18 years age, weighing at least 5 lb, 8 oz (2.5 kg). As of October 2020, both are commercially available. Both drugs can be used to treat older patients.

Treatment courses are 60 days. Adverse effects vary by drug and include rash, nausea, weight loss, and peripheral neuropathy. Patients with severe hepatic or renal insufficiency should not be treated with these medications because they may be unable to adequately metabolize and excrete them. Patients should not be treated during pregnancy but should be evaluated after delivery; treatment should be avoided during breastfeeding.

Cysticercosis

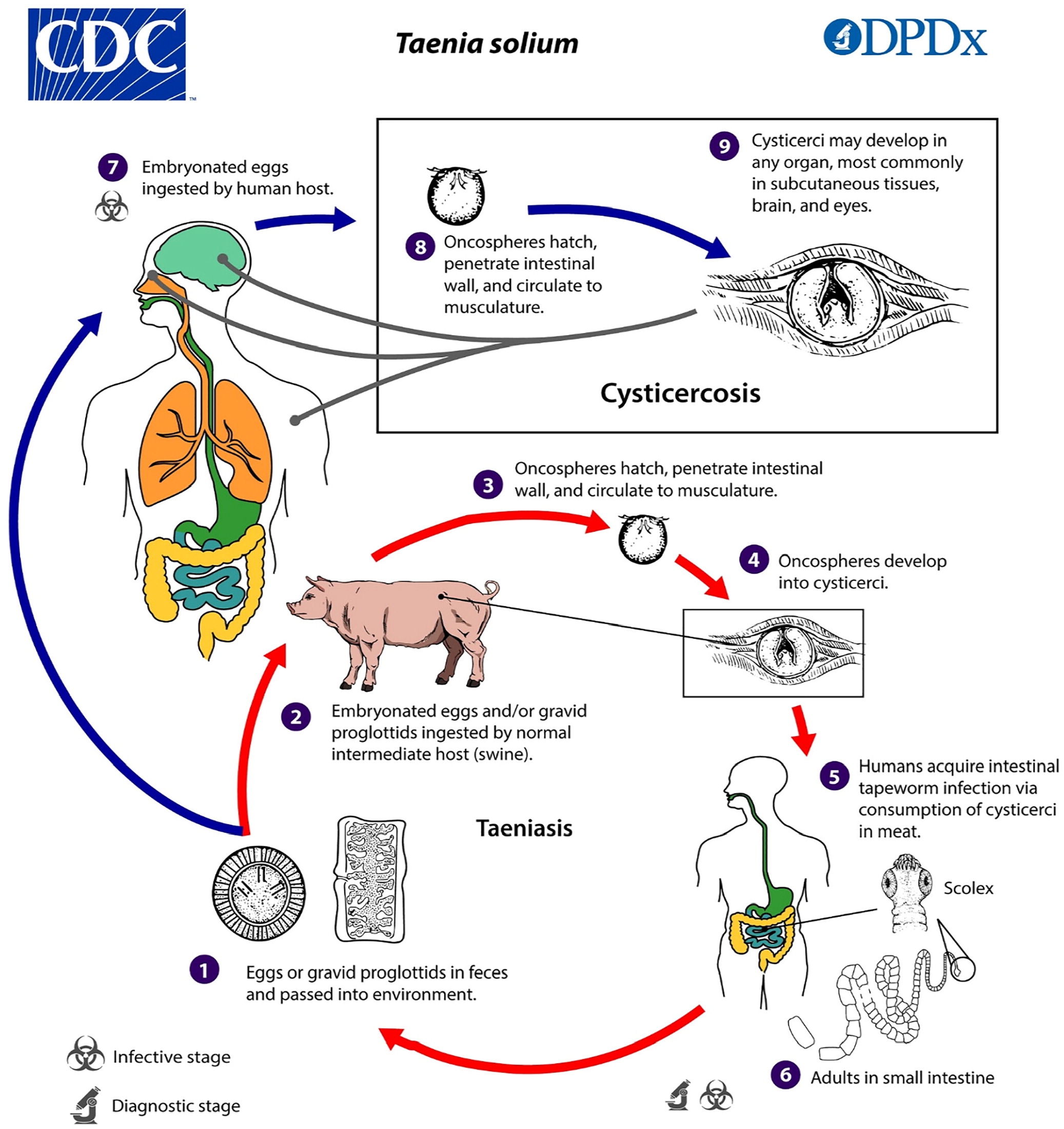

Cysticercosis is a tissue infection with encysted larvae of the Taenia solium tapeworm. If an individual consumes undercooked pork infected with T. solium cysts, that individual can develop an intestinal infection (i.e., taeniasis) with an adult tapeworm. It is usually asymptomatic; however, people with taeniasis shed tapeworm eggs in their feces, which can contaminate the environment or food in settings where personal hygiene practices or access to sanitation is poor. Individuals can then ingest the eggs, which migrate into tissues and develop into larval cysts called cysticerci (Figure 3).9

In the United States, the highest prevalence of cysticercosis is in immigrants from Central and South America. However, up to 15% of patients in a study of cysticercosis-associated deaths were not immigrants.10 Having household contact with a person who has taeniasis increases the risk of cysticercosis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Cysticerci can develop in subcutaneous tissue, muscles, eyes, the brain, or the spinal cord. Symptom onset can be from months to years after the initial infection. Symptoms are usually caused by an inflammatory response to dying parasites but can also be caused by mass effects. Some patients may develop lumps under the skin.

Neurocysticercosis occurs when cysticerci invade the central nervous system. The most common clinical manifestations are seizures, occurring in 50% to 80% of symptomatic patients with parenchymal cysts, and intracranial hypertension or hydrocephalus, which occurs in 20% to 30% of symptomatic patients.11 In endemic areas, up to 30% of seizures are caused by cysticercosis. In one study in the United States, 2.1% of visits to emergency departments for seizures were attributed to neurocysticercosis.12 Other neurologic manifestations include headache, chronic meningitis, and cranial nerve abnormalities. Parenchymal disease with few cysts has a better long-term prognosis than extraparenchymal disease or infection with multiple cysts.13

DIAGNOSIS

Evaluation of patients with cysticercosis is designed to identify patients who may benefit from medical or surgical intervention to prevent or reduce complications.

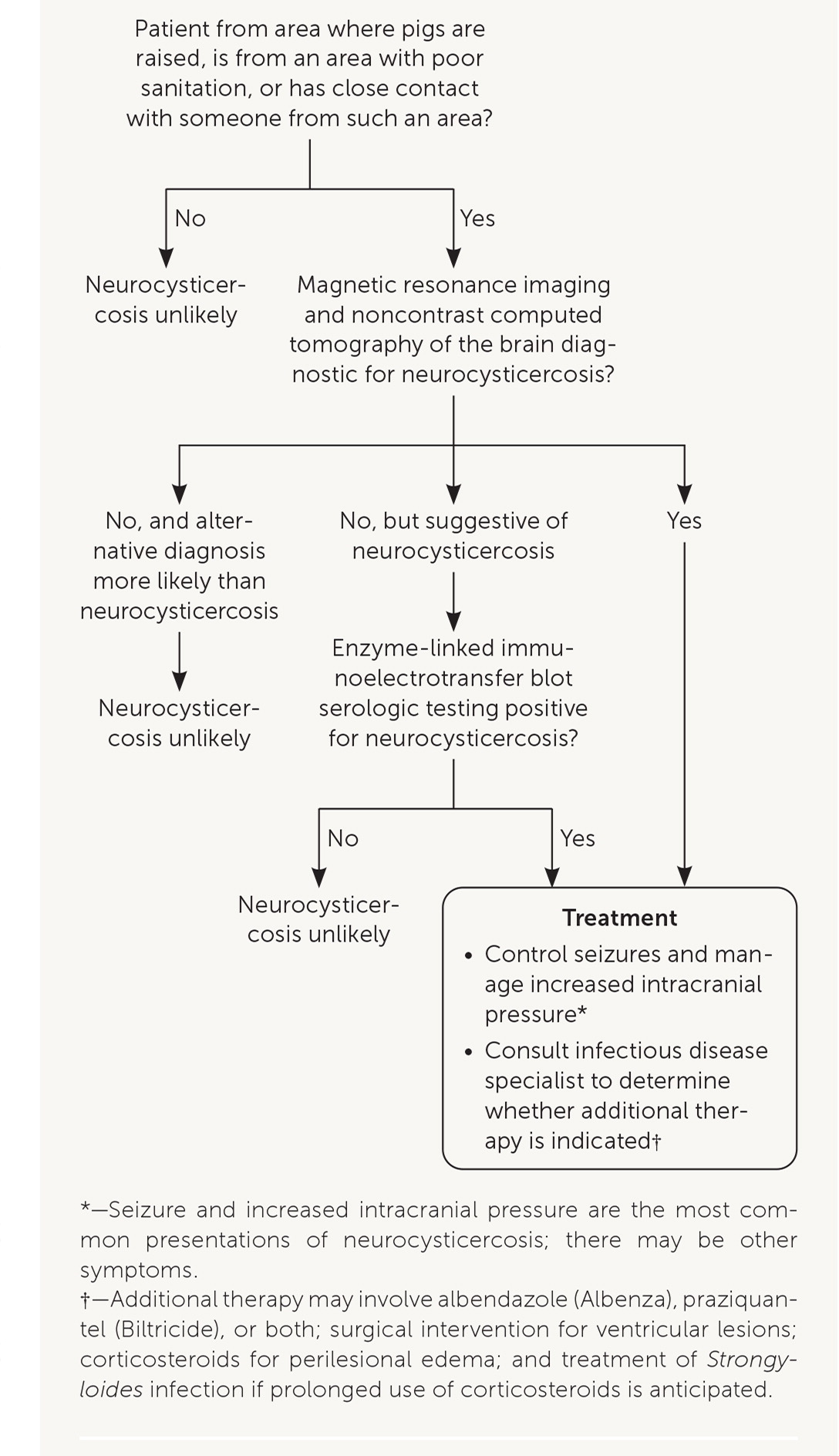

The diagnostic evaluation of patients suspected of having neurocysticercosis is outlined in Figure 4. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are recommended for diagnosis and determining a treatment plan.14 Serologic testing is also recommended to confirm the diagnosis.14 An enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay (available through the parasitic diseases branch at the CDC and some reference laboratories) is the preferred serologic test because its sensitivity and specificity are superior to more readily available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.14

TREATMENT

Initial treatment of neurocysticercosis should focus on symptom control (e.g., antiepileptic drugs for seizures, dexamethasone for edema, neurosurgery for hydrocephalus) instead of immediate initiation of antiparasitic therapy.

When symptoms are controlled, antiparasitic therapy should be individualized, considering the patient's symptoms and the number, viability, and location of cysticerci.14,15 Antiparasitic treatment can cause a severe inflammatory reaction by killing viable cysts; corticosteroids should be used to suppress this response.16 Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis have been published.14 The treatment plan should be developed in collaboration with an infectious disease specialist who has experience treating neurocysticercosis.

If necessary, people diagnosed with cysticercosis and their close contacts should be screened for taeniasis and be treated. Strategies to prevent cysticercosis include handwashing and washing raw vegetables and fruits before eating. People traveling to endemic areas should drink only purified or bottled water and eat only fruits and vegetables that have been cooked or that they have peeled themselves.

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Approximately 11% of people in the United States who are older than six years are estimated to be infected.17 Once an individual is infected, the parasite stays in the body in an inactive state but can reactivate if they become immunosuppressed.

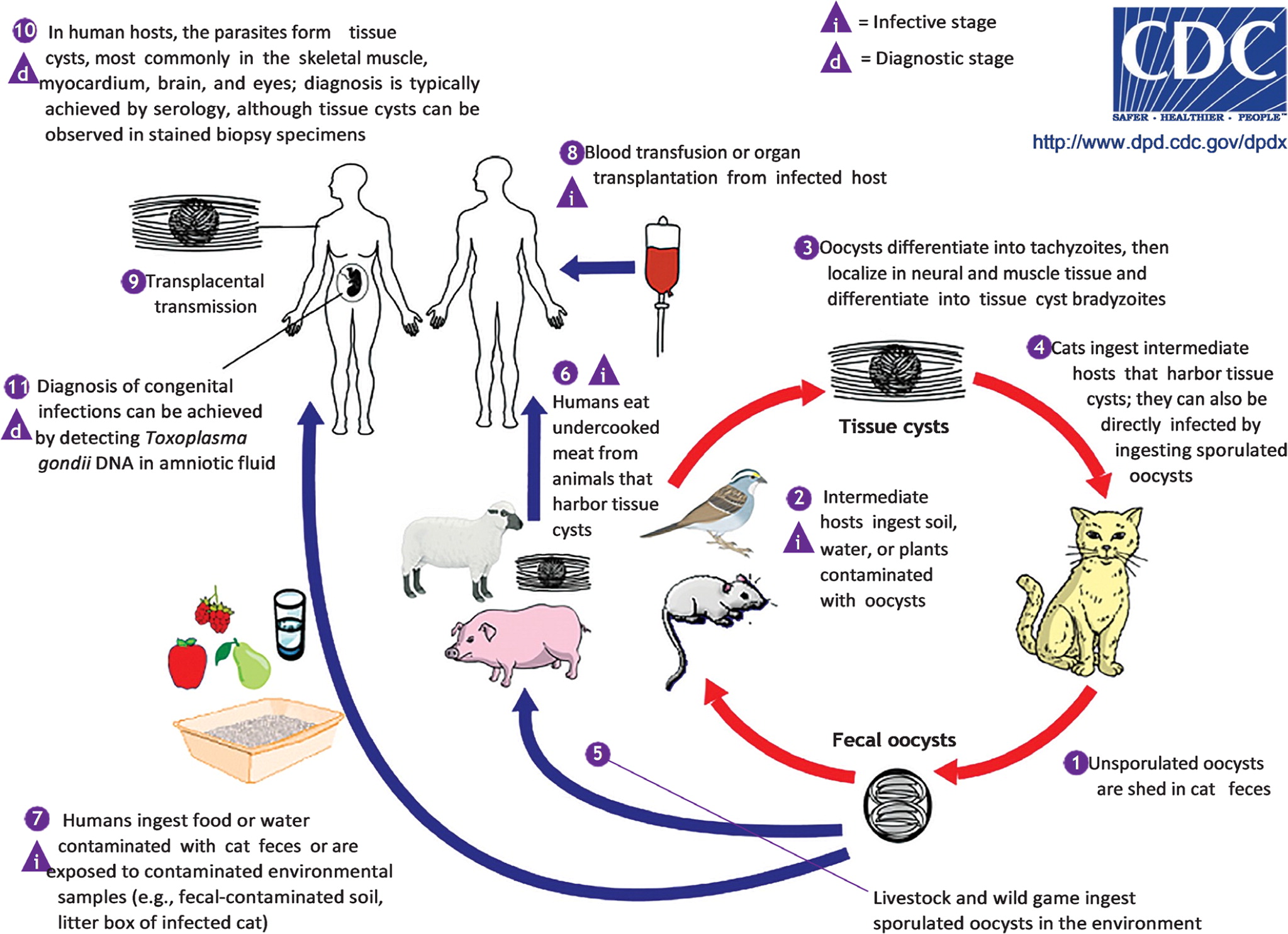

Cats are the definitive host for T. gondii and can shed oocysts in their feces for several weeks after the initial infection. Cats primarily become infected by consuming infected paratenic (transport) hosts, such as small rodents, that have become infected by consuming infective oocysts from the environment.

Humans can become infected by ingesting water or raw fruits or vegetables that have been contaminated with cat feces (Figure 5).17 Humans can also acquire Toxoplasma infection by eating undercooked meat from infected domesticated animals (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats) or wild animals (e.g., deer), or eating food contaminated by raw infected meat.

Transmission can also occur by blood transfusion or organ transplant. Congenital transmission occurs when a patient is newly infected with T. gondii during pregnancy or just before becoming pregnant.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most people who are immunocompetent are asymptomatic; however, some may experience mild flulike symptoms including myalgias, or cervical or occipital lymphadenopathy, that typically resolve spontaneously over several weeks.18 A small percentage (less than 2%) of people infected with T. gondii after birth develop ocular disease.19

Patients with toxoplasmosis who are immunosuppressed may have severe manifestations of infection, including encephalitis, fever, headache, seizures, confusion, or ataxia. These conditions may result from a new infection or reactivation of a previous infection.20

Congenital infections can also occur, but the risk of congenital transmission depends on when maternal infection is acquired, with higher rates of transmission when the infection is acquired later in preganancy.21 If the infection is acquired during pregnancy or within three months of becoming pregnant, there is a risk of congenital transmission. However, if a patient who is immunocompetent acquires the infection earlier than three months before pregnancy, the risk of congenital transmission is essentially zero.22

Congenital infections can result in miscarriage or an infant born with signs of toxoplasmosis (e.g., jaundice, chorioretinitis, ventriculomegaly, hydrocephalus, intracranial calcifications, macrocephaly, microcephaly, seizures).22 Some of these findings may be noted on fetal ultrasound. Congenitally infected infants are often asymptomatic at birth. Ocular disease, usually chorioretinitis, may develop later in life, including in adulthood, in 20% to 80% of people with congenital infection. Symptoms include blurred vision, eye pain, and photophobia.

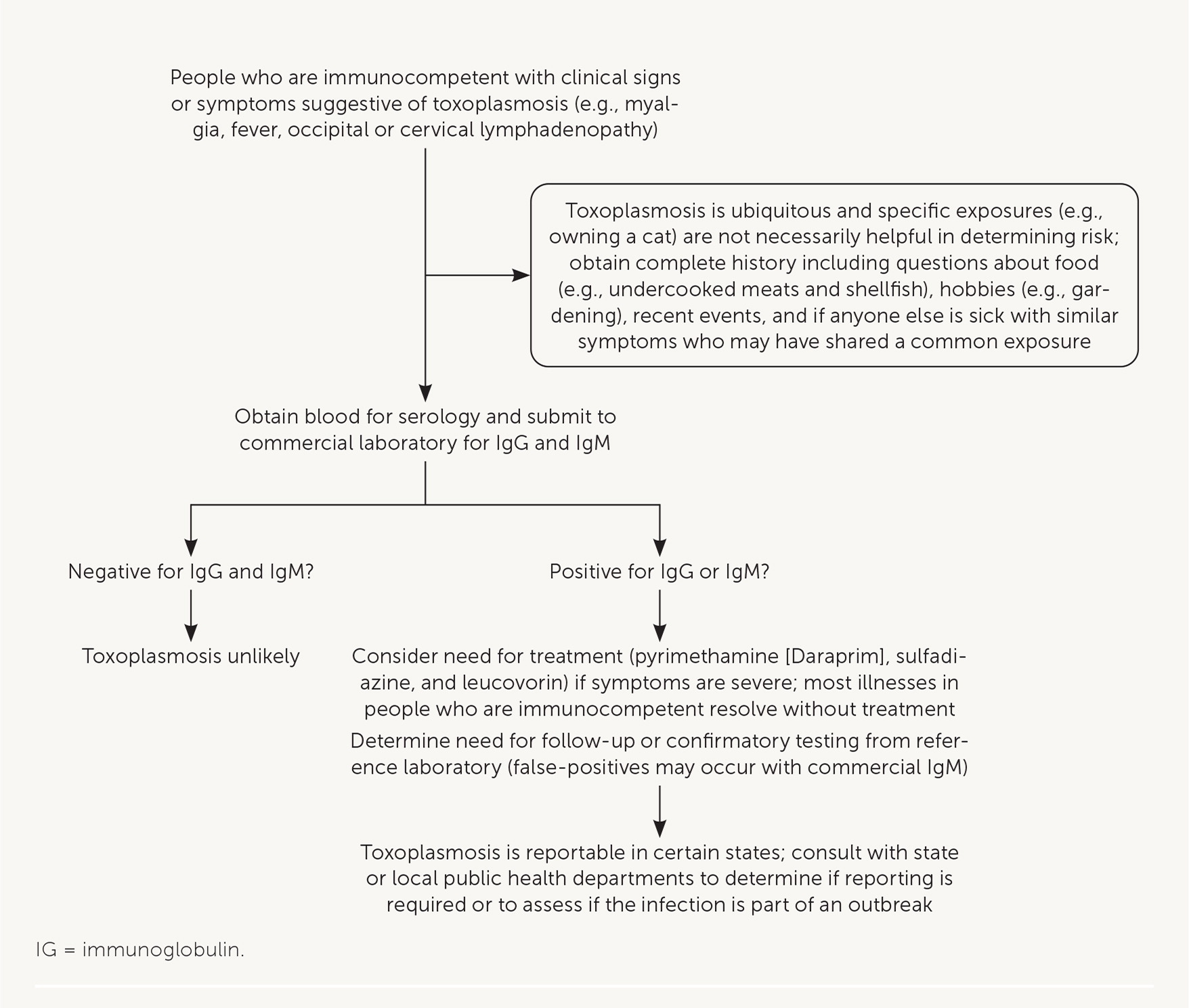

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of toxoplasmosis can be achieved with serologic tests that detect Toxoplasma antibodies (e.g., immunoglobulin [Ig] G, IgM, IgA, IgE; Figure 6). Many commercial and clinical laboratories offer IgM and IgG testing. Polymerase chain reaction testing or direct observation of the parasite in blood, tissue, or cerebrospinal fluid is useful in patients who are immunosuppressed, in whom the diagnosis may be difficult to confirm with antibody tests. In patients with neurologic symptoms, multiple brain abscesses or ring enhancement may be noted on neuroimaging.

Among pregnant patients with suspected disease because of abnormal ultrasonography findings or clinical symptoms of acute infection, commercial IgM and IgG tests are useful, but only for initial testing.22 A diagnosis of acute infection should be confirmed by a reference laboratory that can conduct additional tests (e.g., avidity and agglutination tests) to determine the timing of infection because false-positive results may occur with IgM testing and because IgG may be present in acute (rather than only chronic) infections. In the United States, the Dr. Jack S. Remington Laboratory for Specialty Diagnostics serves as the toxoplasmosis reference laboratory (https://www.sutterhealth.org/services/lab-pathology/toxoplasma-serology-laboratory). To evaluate for congenital transmission to the fetus, ultrasonography and polymerase chain reaction testing of amniotic fluid can be done as early as the 18th week of gestation.

TREATMENT

Treatment of adults who are immunocompetent is rarely warranted because symptoms usually resolve without treatment. If visceral disease is present, or symptoms are severe, pyrimethamine (Daraprim), sulfadiazine, and leucovorin may be administered for two to four weeks (Figure 6). People with toxoplasmosis who are immunosuppressed need continuous treatment until their immunologic state has improved.20

Patients infected during the first or early second trimester of pregnancy should be treated with spiramycin to reduce the risk of transmission of toxoplasmosis to the fetus and is most effective if initiated within eight weeks of maternal seroconversion. Spiramycin can be obtained from the FDA (telephone 301-796-1400). Spiramycin treatment should be continued throughout pregnancy if there is no evidence of fetal infection.22

When there is evidence of fetal infection (confirmed by amniocentesis or suspected based on fetal ultrasonography) or when the infection is acquired during the late second or third trimester, combination therapy consisting of pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and leucovorin is usually administered. Infants with congenitally acquired infection should also receive the pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and leucovorin combination.22

PREVENTION

Patients at risk of severe outcomes from toxoplasmosis (e.g., immunocompromised, pregnant) should be counseled on how to decrease the risk of acquiring infections. Strategies related to food include thoroughly cooking meats and peeling or washing fruits and vegetables before eating; washing food preparation materials after contact with raw meat or unwashed fruits or vegetables; avoiding drinking unpasteurized milk and untreated or contaminated water; and avoiding eating raw or undercooked shellfish (e.g., oysters, mussels, clams) because they may be contaminated with oocysts washed into seawater.23

Patients should wear gloves when gardening or during any contact with soil or sand, wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after contact with soil or sand, and keep sandboxes covered when not in use.

Strategies related to cats include preventing cats from hunting and changing litter boxes daily. However, pregnant patients and people who are immunosuppressed should avoid cleaning litter boxes if possible. When people who are immunosuppressed must perform this task, they should wear disposable gloves and wash their hands thoroughly with soap and water afterward. These patients should also avoid adopting stray cats, especially kittens.

This article updates a previous article on this subject by Woodhall, et al.2

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and United States for each of the following diseases: Chagas disease, cysticercosis, and toxoplasmosis. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The CDC website was also reviewed. Search dates: March 1, 2020 and April 8, 2021.

The findings and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC.

Further information about Chagas disease, toxocariasis, cysticercosis, and toxoplasmosis is available through the CDC website (http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/npi.html). Resources include fact sheets for patients and physicians, continuing medical education courses, and audio podcasts for each disease. Consultation with experts and information about diagnostic testing and investigational drugs are available through the Parasitic Diseases Branch Public Inquiries desk (telephone: 404-718-4745; email: parasites@cdc.gov).