Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(1):40-50

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Approximately 7% of children in the United States younger than 18 years have a diagnosed eye disorder, and 1 in 4 children between two and 17 years of age wears glasses. Routine eye examinations during childhood can identify abnormalities necessitating referral to ophthalmology, which optimizes children's vision through the early diagnosis and treatment of abnormalities. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends vision screening at least once in children three to five years of age to detect amblyopia or its risk factors to improve visual acuity. The American Academy of Family Physicians supports this recommendation. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening starting at three years of age and at regular intervals in childhood, and that instrument-based screening (e.g., photoscreening, autorefraction) is an alternative to vision charts for testing visual acuity in patients three to five years of age. Eye examinations include visual acuity testing, external examinations, assessing ocular alignment and pupillary response, and assessing for opacities with the red reflex examination. Common abnormalities include refractive errors, amblyopia (reduction in visual acuity in one eye not attributable to structural abnormality), and strabismus (misalignment of the eye). Rare diagnoses include retinoblastoma (often detectable through loss of red reflex), cataracts (detectable by an abnormal red reflex), and glaucoma (often manifests as light sensitivity with corneal cloudiness and enlargement).

Approximately 7% of children in the United States younger than 18 years have a diagnosed eye disorder, and 1 in 4 children between two and 17 years of age wear glasses.1,2 Routine eye examinations and vision screening during well-child examinations can identify risk factors and abnormalities consistent with those eye disorders and lead to a referral to ophthalmology. Subsequent diagnosis and treatment can optimize a child's eye health and vision, thereby minimizing or avoiding developmental delays, impaired school performance, and problems with social interactions and self-esteem.3

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Annual comprehensive eye examinations are unnecessary for children who pass routine vision screening assessments. | American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus |

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends vision screening at least once in all children three to five years of age (grade B recommendation) to detect amblyopia or its risk factors to improve visual acuity.4 The benefits of vision screening to detect amblyopia or its risk factors in children younger than three years are uncertain according to the USPSTF, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined (grade C recommendation).4 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports this recommendation.5 The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends that components of the visual screening occur at every well-child examination6 (Table 16–8). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends beginning vision screening at four to five years of age and as early as three years of age in cooperative children.9 Instrument-based screening (e.g., photoscreening) is recommended starting at 12 months of age.10,11

| Method | Indications for referral | Implication | Recommended age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn to six months | Six months and until the child is able to cooperate for subjective visual acuity measurement | Three to four years | Four to five years | Every one to two years after five years of age | |||

| External inspection | Structural abnormality (e.g., ptosis) | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Fix and follow test | Failure to fix and follow | Strabismus | Cooperative infant older than three months | X | |||

| Pupillary examination | Irregular shape, unequal size, poor or unequal reaction to light | Horner syndrome, retinoblastoma | X | X | X | X | X |

| Red reflex examination | Absent, white, dull, opacified, or asymmetric | Retinoblastoma, cataract, glaucoma, retinal abnormality | X | X | X | X | X |

| Corneal light reflex test | Asymmetric or displaced | Strabismus | X | X | X | X | |

| Cover test | Covered eye moves back to alignment when uncovered | Strabismus | X | X | X | X | |

| Instrument-based screening* | Failure to meet screening criteria based on instrument guidelines | Amblyopia, refractive errors, strabismus | Can be used to assess risk when available | X | X | X | |

| Distance visual acuity† (monocular) | 20/50 or worse in either eye | Amblyopia, vision impairment | X | X | X | ||

| 20/40 or worse in either eye | X | X | |||||

| Worse than three out of five characters on 20/30 line, or two lines of difference between the eyes | X | ||||||

History

| Personal history Cerebral palsy* Down syndrome* Premature birth* Family reporting history of eye deviation (may only occur when child is tired) Head tilting, resisting covering of one eye, concern for amblyopia | Family history Amblyopia* Childhood cataracts* Childhood glaucoma* Ocular or genetic syndrome disease* Retinoblastoma* Strabismus* Childhood use of eyeglasses in parents or siblings Eye surgery | Ask at each observation Has your child ever had an eye injury? Does your child seem to see well? Does your child exhibit difficulty with near or distance vision? Do your child's eyes appear unusual? Do your child's eyelids droop or does one eyelid tend to close? Do your child's eyes appear straight or do they seem to cross, particularly when they are tired? |

Eye Examination

The eye examination should include an external examination, pupillary response, corneal light reflex, red reflex, fixation and alignment, cover and cover-uncover, and visual acuity testing. American Family Physician provides videos demonstrating eye examinations in infants/toddlers (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4hjONYSfjS8) and preschoolers (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRqk5vqWMy0).

PUPILLARY RESPONSE

Pupillary response should be assessed in light and darkness using a light source to illuminate the pupil while the child's attention is directed toward a remote target of interest (e.g., a toy). Pupils should be compared for size and symmetry. A difference in pupil size greater than 1 mm can be a sign of underlying pathology.

CORNEAL LIGHT REFLEX

To test the corneal reflex, the clinician should center light on the pupils to assess if there is an equal light reflex. This can be accomplished most naturally during the external inspection and assessment of pupillary response. A toy in front of the child can help keep the child's gaze still, making the assessment easier.

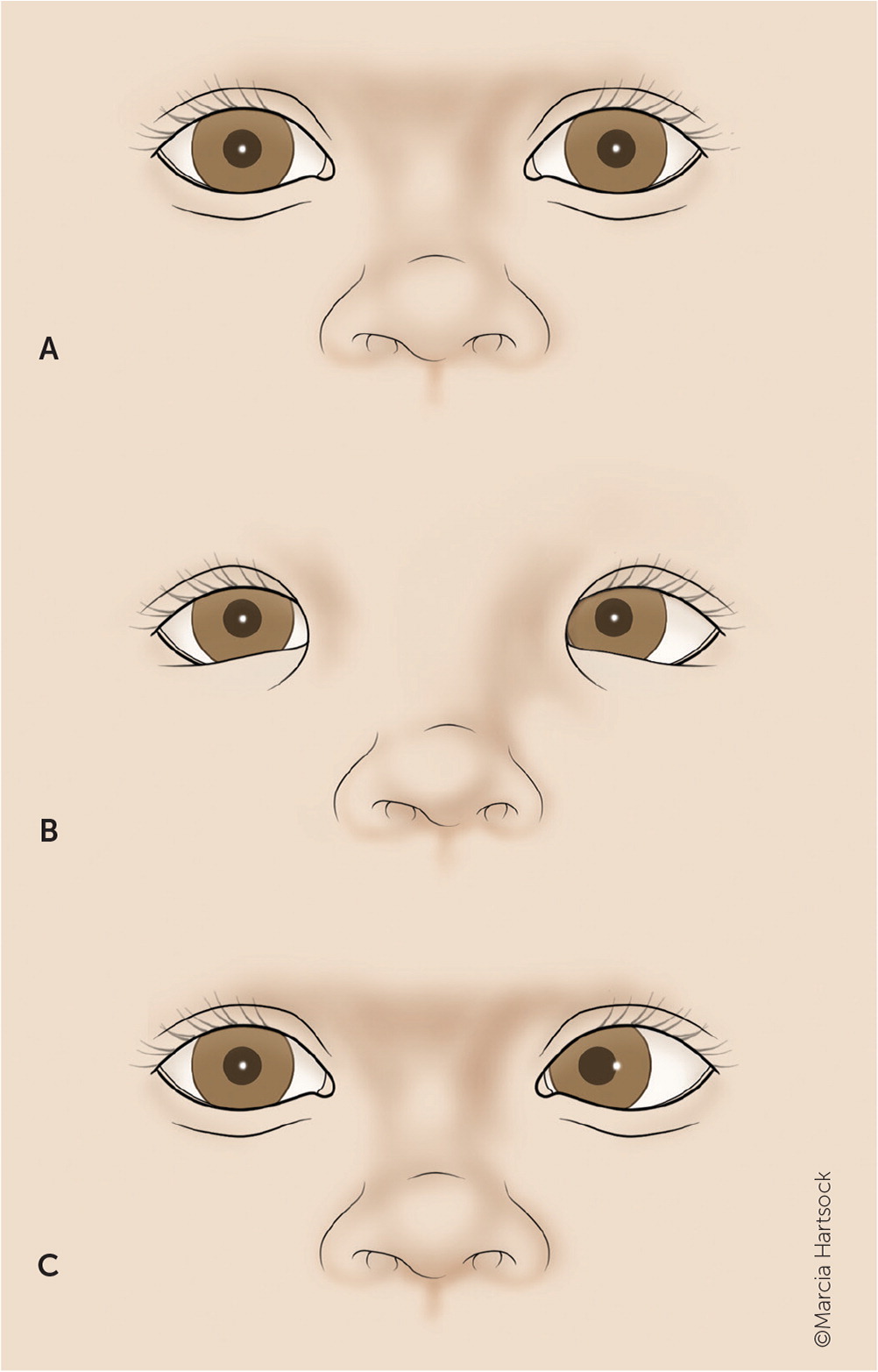

Light reflex should be symmetric by four to six months of age. Light reflex helps differentiate pseudostrabismus from strabismus (i.e., a misalignment of the eyes). A light reflex in patients with pseudostrabismus is normal despite a wide nasal bridge or epicanthal fold that may initially make the eyes appear to be misaligned (Figure 1 and Figure 212).

RED REFLEX

Red reflex testing is recommended starting in the neonatal period and continuing through subsequent well-child examinations. This test is critical for detecting vision and serious abnormalities such as cataracts, glaucoma, retinoblastoma, retinal disorders, systemic diseases with ocular manifestations, and high refractive errors.6

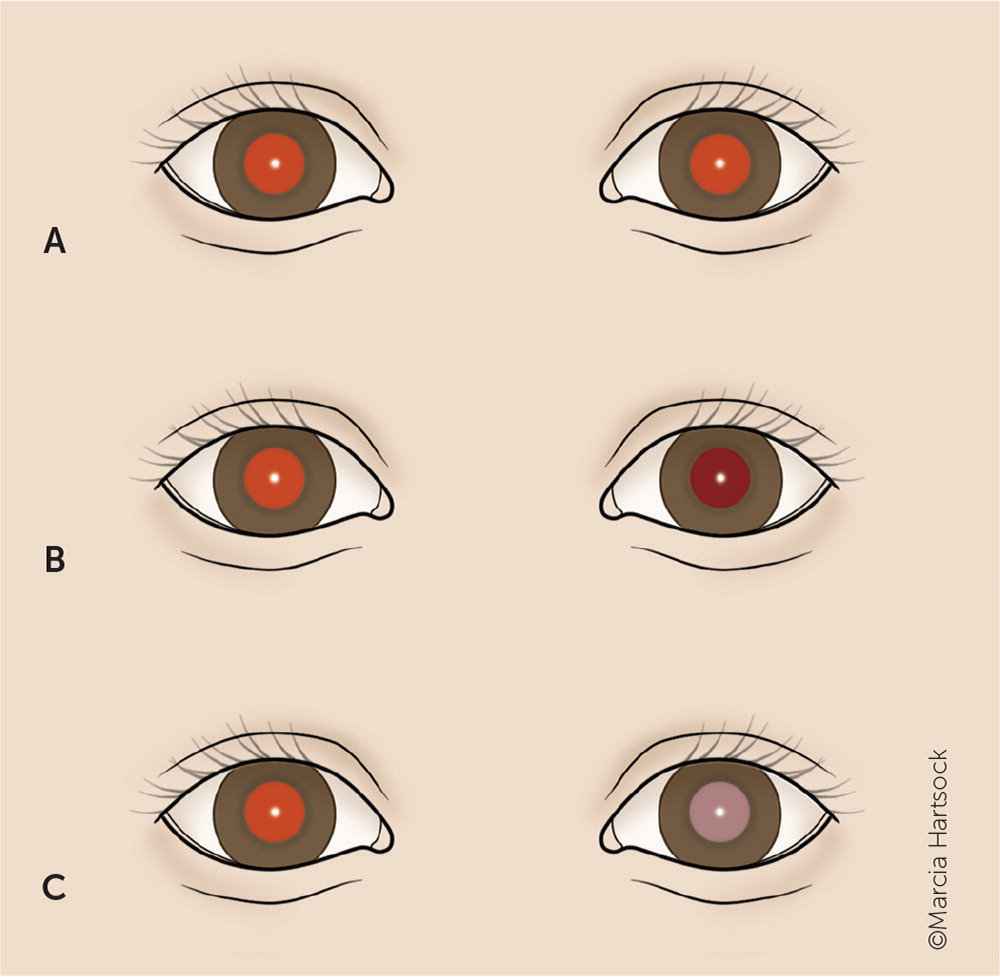

The child is held or seated in a darkened room in a comfortable position that allows the clinician to view both pupils. The ophthalmoscope lens is held 18 inches (46 cm) away from the child. The light source should illuminate both eyes and be equal in reflectance. Abnormal reflexes can include diminished reflex, dark spots, a white reflex, or asymmetry between the eyes6 (Figure 312).

FIXATION AND ALIGNMENT

Typically, children as young as six weeks have some response to the examiner's face. By two months of age, the infant should consistently fix and follow; however, before two months of age, it is normal for one or both eyes to deviate temporarily. A failure to fix and follow in a room with visual distractors may be a sign of delayed visual maturation. By two months of age, this should resolve.

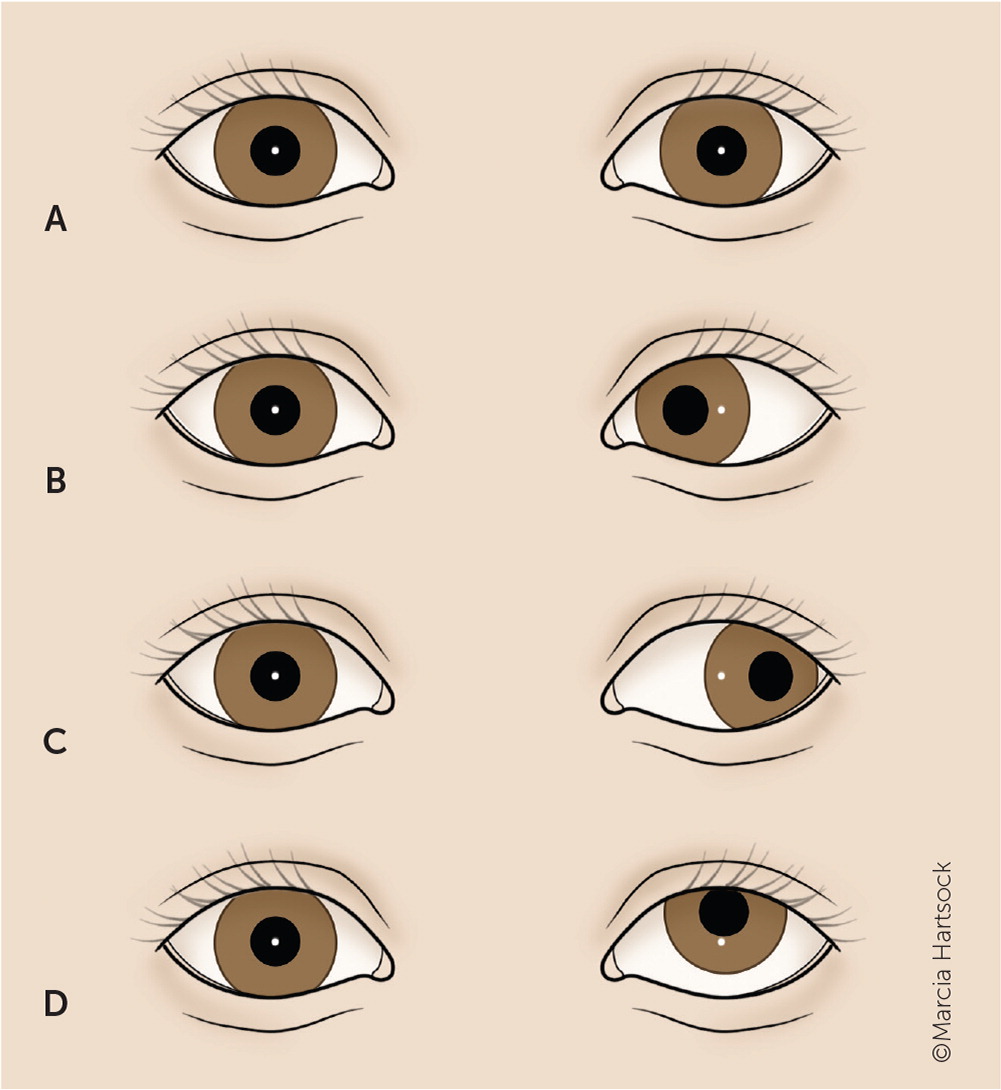

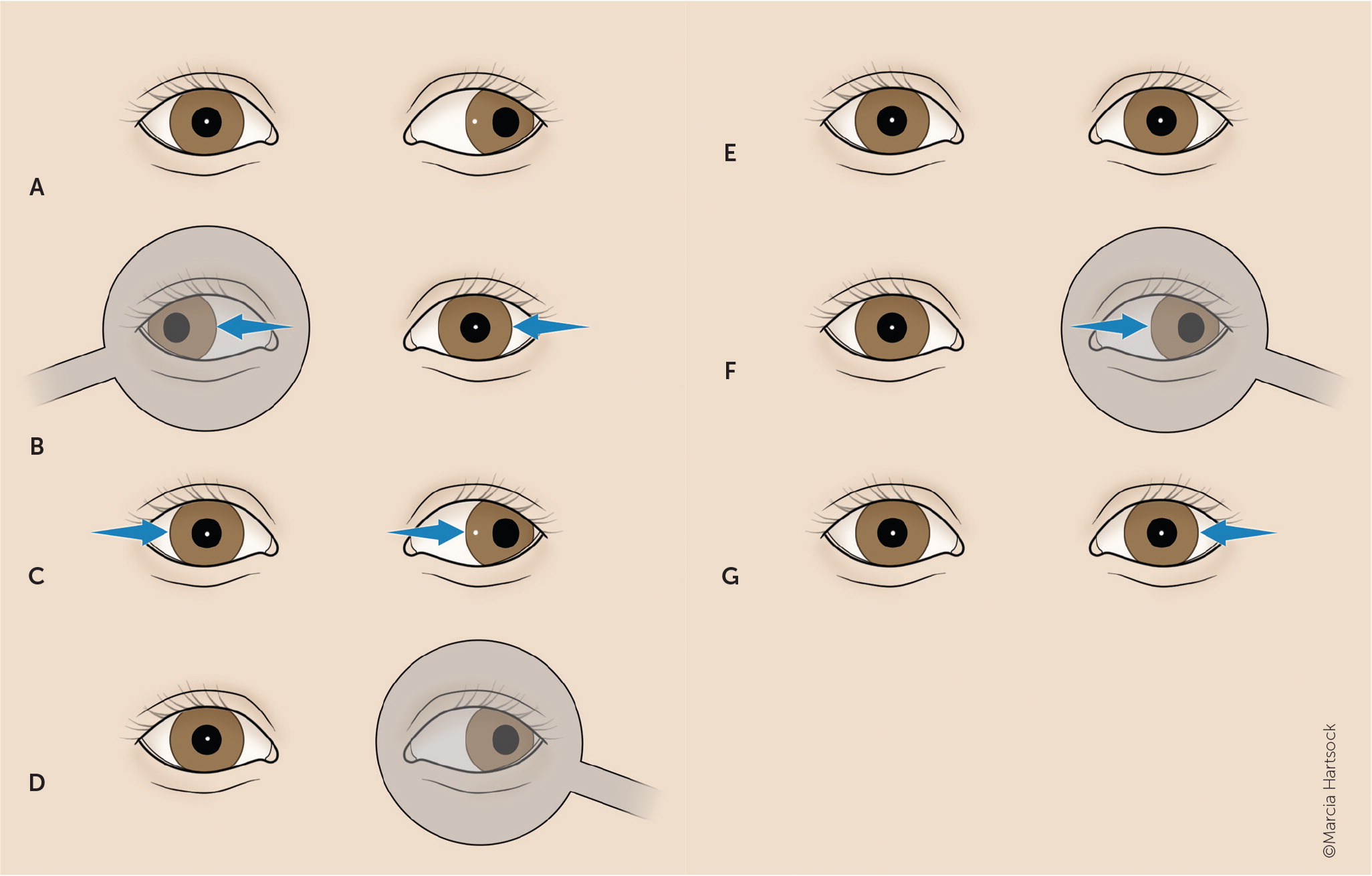

COVER AND COVER-UNCOVER TESTS

Cover and cover-uncover tests assess for strabismus. Tropia is a deviation of the eye, also known as manifest strabismus, whereas phoria is latent strabismus. An exophoria is a type of strabismus that is evident only temporarily when the child is stressed or tired. An exotropia is a type of strabismus that occurs more frequently and is often more noticeable than other types of strabismus. The examiner will observe that one eye appears deviated (affected or strabismic) and the other is fixed on an object (unaffected or fixating). When the fixating eye is covered, the strabismic eye will move into alignment. When the fixating eye is uncovered, the strabismic eye will return to its deviated position. If the strabismic eye is covered, the fixating eye will not move (Figure 4).12

In the cover-uncover test, the child's attention is attracted to a distant or near target and eye alignment is observed. The eye to be tested is covered for a few seconds. On uncovering the eye, it will be out of alignment and move back to alignment. This is a positive test for exophoria. Minimal phoria can be a normal variant. The eye alignment may look normal on binocular viewing, but movement is noted after one eye is occluded. A positive test to a near target is consistent with an accommodative esotropia if the eye turns in because the child has uncorrected farsightedness. If the eye turns out while viewing a distant target, the child has intermittent exotropia, which is the most common form of strabismus and can be caused by problems with innervation or uncorrected nearsightedness.

The alternating cover test can also measure binocular eye involvement. Rapid alternate covering of each eye may elicit a latent eye movement, including esophoria and exophoria.13

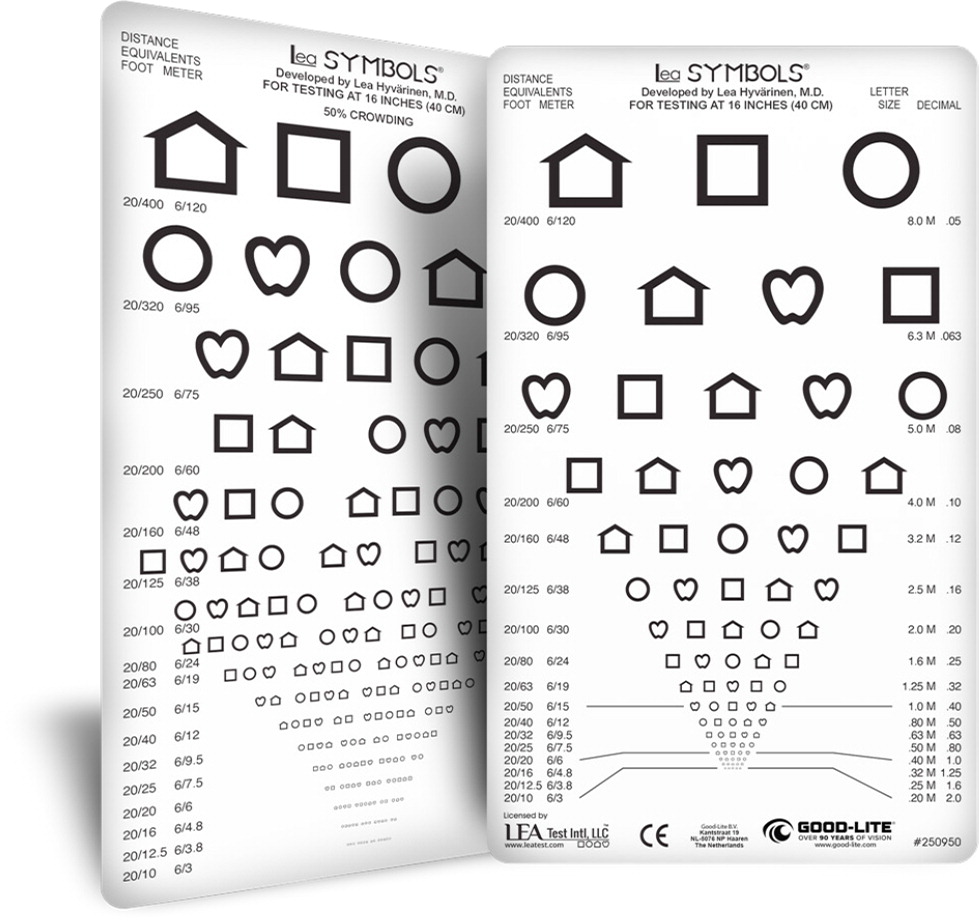

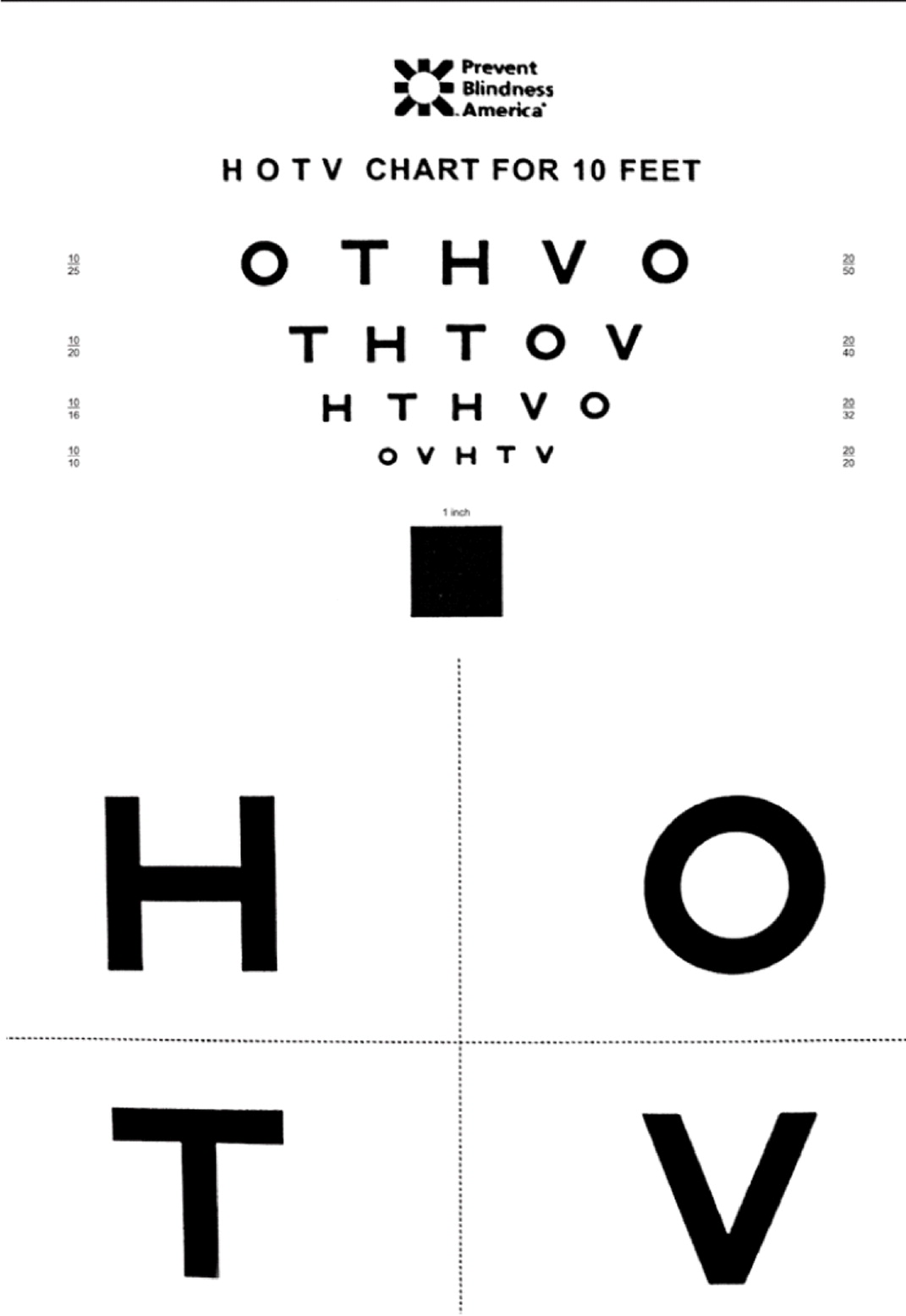

VISUAL ACUITY

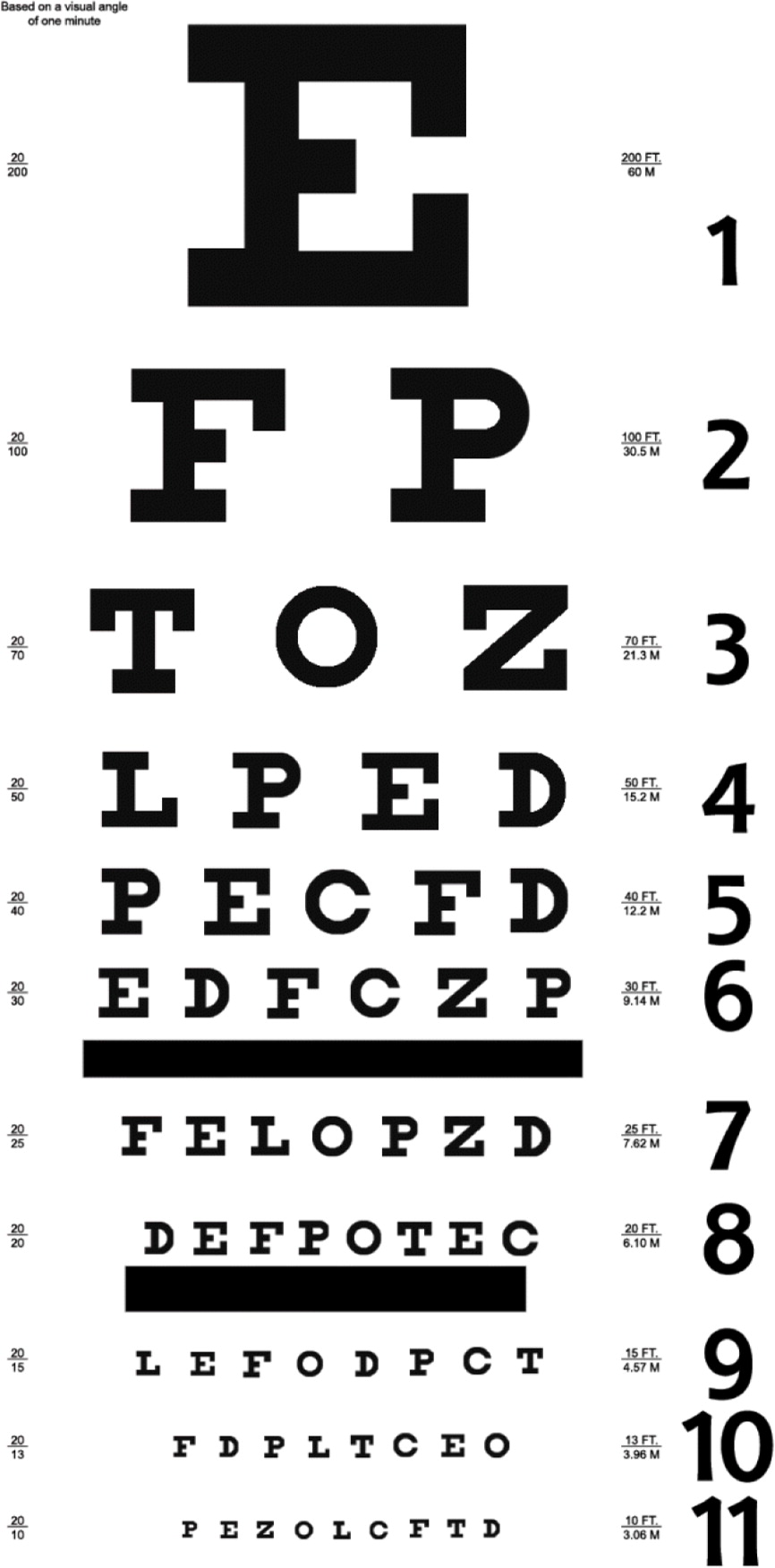

Each eye should be tested independently, with the opposite eye occluded to discourage peeking. The Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study provided updated norms for visual acuity in children between two and five years of age16 (Table 311,12,16). At any age, visual acuity should be equal between both eyes (no more than two lines different). Most children do not have 20/20 vision until after six years of age.16

When testing, the large letters or figures at the top of the chart should be reviewed with both child's eyes open to help them understand the test. Then, one eye is occluded to perform the test.

The threshold line or critical line evaluation may be used. Threshold line testing asks the child to start at the top of the eye chart and read down each line until they reach the smallest line they can discern with each eye separately. Although this allows the health care professional to identify the best acuity level in each eye and detect children with near-normal acuity who have a mild difference between each eye, it is time-consuming and easy to lose the child's attention. The critical line method can be more quickly administered and can be an alternative to detect children with potentially serious vision concerns. The child is asked to read the “critical line” for their age, and if they can, it is unnecessary to measure below the age-specific critical line11 (Table 311,12,16).

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends referral for children five years and older who cannot read three or more letters or figures on the 20/30 line or has a two-line difference between eyes because this may indicate amblyopia (i.e., one eye has worse visual acuity than the other).6

INSTRUMENT-BASED SCREENING

Instrument-based screening using photoscreening or autorefraction can detect ocular risk factors that may result in vision loss in children. Photoscreening devices use optical images of the red reflex to detect refractive errors and strabismus.17 Autorefractors use automated retinoscopy to evaluate refractive error and are particularly useful in preverbal children, young children, or older children who are noncooperative or nonverbal.11,18

Instrument-based screening is more time efficient, and one study found a higher positive predictive value among children three to four years of age compared with conventional screening methods.19 Instrument-based screening is considered by many to be the standard of care. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends instrument-based vision screening as an alternative to vision charts for annual screening in patients three to five years of age and as a tool to assess risk at 12 and 24 months.7,8,10,11 Routine visual acuity screening with a Snellen chart can be used for patients who are five years and older.10

Common Eye Disorders

AMBLYOPIA

Amblyopia (i.e., lazy eye) is a reduction in best-corrected visual acuity in one eye that is not directly attributable to a structural abnormality of the eye or visual pathway. Amblyopia should be suspected in any child that shows signs of strabismus, resists having one eye covered, tilts the head, squints with one eye, or has a family history of congenital cataracts, congenital glaucoma, or amblyopia.20

Amblyopia is present in 1.4% of the population globally and 2.4% of the population of North America.21 Amblyopia is the leading cause of monocular vision impairment in people 20 to 70 years of age (2.9% of adults).22 There are multiple causes of amblyopia, with each resulting in visual impairment due to the brain learning to suppress the poorer image from the affected eye (Table 4).23

| Type | Cause | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Strabismic (50%) | Representation of the retinal image in the strabismic eye is cortically suppressed, which prevents double vision | Most common cause; diagnosis may be difficult if the deviation is small |

| Refractive (17%) | Two eyes have significantly different refractive power (nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism); can appear alone or in combination with strabismus (30%) | Most difficult to detect because gross eye alignment and appearance of the two eyes are otherwise normal; these children often demonstrate adverse responses to occlusion of the preferred eye; reduced vision in both eyes that appear to be otherwise normal may indicate bilateral amblyopia due to extreme farsightedness or nearsightedness |

| Deprivation (≤ 3%) | Retinal image is blurred and lacks spatial detail owing to obstruction of the visual axes; can be due to cataracts, opacities, severe ptosis, excessive patching | Most severe in terms of vision loss |

Early detection through vision screening before seven years of age is crucial because, without treatment, amblyopia can lead to irreversible, lifelong visual deficits.12,24 Although there is insufficient evidence to show screening for amblyopia before three years of age has benefits, screening all children three to five years of age is recommended because detection and treatment of amblyopia leads to moderate improvements in visual acuity.4

Treatment of amblyopia begins with correcting refractive errors with eyeglasses and treating pathology that is reducing the quality of images projected onto the retina and transmitted to the brain. Once mitigating factors, such as congenital cataracts, are corrected, interventions stimulate the affected eye and optimize the development of the visual pathways. Treatment options include correcting refractive errors, patching the unaffected eye, pharmacology, Bangerter filters (of varying opacity levels) on the unaffected eye, and surgery to remove optical interference or improve binocular alignment (Table 525–29). Treatment should be implemented during the critical period (three to five years of age) and monitored closely to optimize outcomes.30

| Patching of the unaffected eye | |

| Moderate amblyopia (20/40 to 20/80) | 2 to 6 hours daily25 |

| Severe amblyopia (20/100 to 20/400) | 6 to 24 hours daily26 |

| Atropine | |

| Moderate amblyopia (20/40 to 20/100) | 1 drop daily had similar results to 6-hour patching at 15-year follow-up27 |

| Moderate amblyopia (20/40 to 20/80) | Weekend atropine had similar results to daily atropine28 |

| Bangerter filter on the unaffected eye | |

| Moderate amblyopia (20/40 to 20/80) | Daily filter use had similar results to daily patching with less inconvenience; one possible advantage to the use of filters is optimization of binocular visual development29 |

STRABISMUS

Strabismus is the misalignment of the eyes and is present in up to 4% of children; 40% will develop amblyopia.6 Strabismus is categorized by the direction of the deviating eye relative to the fixating eye: esotropia-in, exotropia-out, hypertropia-up, hypotropia-down.

Esotropia is the most common type of early-onset strabismus. It can be acquired or congenital. The most common acquired esotropia is accommodative esotropia, which is attributed to farsightedness and typically appears between 18 and 36 months of age, but can emerge earlier or later. Treatment primarily is correcting farsightedness with eyeglasses, often bifocals (such as those used by adults with separate lenses for distance and near vision). If persistent, surgical correction can be considered. This type of esotropia can lead to amblyopia if untreated.31

Congenital esotropia is characterized by an excess of convergence and carries a high risk of developing amblyopia. Treatment (most often surgery to correct the muscular imbalance, although onabotulinumtoxinA is sometimes used) should be implemented by six months to two years of age to maximize the potential for good binocular development.32

In most cases, exotropia is intermittent and first noticed when a child begins preschool. Parents may observe that their child's eye tends to wander when they are tired or inattentive. The child can usually correct the exotropia when attentive to their visual surroundings.6 Surgical correction is indicated when the exodeviation is constant, frequent, or so large that it is unacceptable to the child or the parent/caregiver.33

Hypertropia and hypotropia are difficult to diagnose due to numerous potential etiologies, and may be difficult to notice on casual inspection. If either of these conditions are suspected, the patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist or neurologist for further diagnostic evaluation because of the complexity of this subset of patients with strabismus. A subset of these children may have an underlying vestibular disorder.31

RETINOBLASTOMA, CATARACT, GLAUCOMA

Although rarer than amblyopia or strabismus in children, a diagnosis of retinoblastoma, childhood cataracts, or glaucoma should not be missed.

Retinoblastoma is the most common intraocular malignancy and the seventh most common malignancy in childhood, accounting for 2% of childhood cancers.34 Diagnosis is usually made by noting the absence of red reflex (leukocoria), although other findings may be present, including strabismus, tearing, red eye, iris discoloration, corneal clouding, hyphema, or glaucoma.35 Retinoblastoma can result in the blindness of one or both eyes and can be fatal, but early detection can result in cure rates greater than 90%. Patients diagnosed with retinoblastoma should have regular follow-up because up to 45% of those treated with eye-preserving therapy have a recurrence or a new ocular tumor.36 Genetic testing is imperative because 50% of patients with germline mutations develop a second nonocular malignant neoplasm by 50 years of age.37

Cataracts can be congenital (nuclear, nonprogressive) or develop during infancy (lamellar, progressive) and are mostly idiopathic, with about one-third being hereditary.38 Gross or penlight examination may show dull, irregular, or absent red reflex or white pupil. The prevalence is 1 to 6 out of 10,000.38

Congenital glaucoma, which can affect one or both eyes, is caused by a developmental defect in the iridocorneal angle of the anterior chamber that obstructs the outflow of aqueous fluid. The increased pressure causes corneal edema and enlargement of the globe. Although glaucoma is uncommon in children (affecting less than 0.05%), children with a history of cataract surgery, Sturge-Weber syndrome, anterior segment malformations, aniridia, retinopathy of prematurity, ocular trauma, and posterior segment malformations are at risk.39 The examination will find a child who is uncomfortable and light sensitive with bilateral or unilateral corneal cloudiness and enlargement. Children who have lacrimal duct obstruction with excessive tearing that does not resolve with conservative measures after one year of age should be referred to an ophthalmologist because glaucoma may present similarly.40

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Bell, et al.12; Simon and Kaw41; and Broderick.31

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term pediatric eye examination. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Cochrane database, DynaMed, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: July 9, 2022, and May 9, 2023.