Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):137-147

Related Letter to the Editor: Rapid Removal of a Bee Stinger

Patient information: See related handout on how to protect yourself from ticks, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Arthropods, including insects and arachnids, significantly affect humans as vectors for infectious diseases. Arthropod bites and stings commonly cause minor, usually self-limited reactions; however, some species are associated with more severe complications. Spider bites are rarely life-threatening. There are two medically relevant spiders in the United States. Widow spider (Latrodectus) envenomation can cause muscle spasm and severe pain that should be treated with analgesics and benzodiazepines. Antivenom is not widely available in the United States but may be considered for severe, refractory cases. Recluse spider (Loxosceles) bites are often overdiagnosed, should be treated supportively, and only rarely cause skin necrosis. Centruroides scorpions are the only medically relevant genus in the United States. Envenomation causes neuromuscular and autonomic dysfunction, which should be treated with analgesics, benzodiazepines, supportive care, and, in severe cases, antivenom. Hymenoptera, specifically bees, wasps, hornets, and fire ants, account for the most arthropod-related deaths in humans, most commonly by severe allergic reactions to envenomation. In severe cases, patients are treated with analgesia, local wound care, and systemic glucocorticoids. Diptera include flies and mosquitoes. The direct effects of their bites are usually minor and treated symptomatically; however, they are vectors for numerous infectious diseases. Arthropod bite and sting prevention strategies include avoiding high-risk areas, covering exposed skin, and wearing permethrin-impregnated clothing. N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) 20% to 50% is the most studied and widely recommended insect repellant.

Arthropods, comprised of insects and arachnids, account for up to 1 million emergency department visits annually in the United States.1 Arthropods' most significant effects on humans are as vectors for infectious diseases, and direct effects of their bites and stings are typically only a self-limited nuisance (Table 12–5). Local effects can be treated symptomatically with topical or oral antihistamines, calamine lotion, topical corticosteroids, cold compresses, or, in severe cases, systemic glucocorticoids. There are limited data to support one treatment over another.

| Arthropod | Clinical manifestations | Body distribution | Geographic distribution | Associated vector-borne diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus) | Simple: erythematous, pruritic macules or papules, 2 mm to 5 mm Complex: pruritic wheal around central punctum, urticaria, progressive bullous rash with secondary infection | All body regions, most commonly on the back or on warm or occluded regions of the body | Temperate regions throughout North America | None |

| Biting midges (Ceratopogonidae) | Sharp burning pain with resulting papule, bite often not witnessed | Head and neck | Throughout North America, predominantly in coastal, marshy areas | Mansonellosis (Africa and tropical Americas) |

| Brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) | Initially painless or occasional burning Single, red papule with central pallor Can become painful and necrotic | Upper arm, thorax, inner thigh (rolling onto spider in bed or trapping in clothing) | Southern Midwest and Southwestern United States | None |

| Fleas (Ctenocephalides felis and Oropsylla montana) | Erythematous pruritic maculopapular lesions, less than 1 cm | Typically lower extremities (feet or ankles) | Throughout United States; vectors of human pathogens primarily in western United States, Texas, Hawaii | Cat-scratch fever, flea-borne (murine) typhus, plague |

| Horseflies and deer flies (Tabanidae) | Bites are deep, painful, and wounds tend to bleed after flies have left | Most commonly on exposed skin, but can bite through clothing; bites occur most often during the day | Throughout North America | Anthrax, loiasis, tularemia |

| Mites and chiggers (Sarcoptes scabiei and Trombicula spp. ) | Localized pruritic erythematous papules or burrows | Typically on constrictive clothing lines (beltlines, socks), wrists, between fingers | Throughout United States in cool areas with high humidity and dense vegetation | Rickettsialpox, scrub typhus (Asian-Pacific region) |

| Mosquitoes (Culicidae) | Intensely pruritic papules, sometimes result in wheal-and-flare reaction, can result in dramatic surrounding induration | Exposed skin | Northeast, South, West coast | Japanese encephalitis, lymphatic filariasis, malaria, West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis, western equine encephalitis, eastern equine encephalitis, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, Ross River virus, Rift Valley fever virus, dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, zika |

| Sandflies (Phlebotomus, Lutzomyia) | Bites may be painless, mildly painful, or intensely pruritic; result in small papules | Exposed skin; bites occur most often at night | Throughout North America | Leishmaniasis, sandfly fever, bartonellosis (Carrión disease), papataci fever (three-day fever) |

| Ticks (Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor andersoni, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Amblyomma americanum, Ornithodoros genus) | Local: expanding erythematous patch initially homogenous then progressing with central clearing over a few days (erythema migrans) or macular rash Systemic: neurologic (meningitis, facial palsy), musculoskeletal (arthralgias, myalgias) cardiovascular (temporary atrioventricular block) Flulike symptoms, lymphadenopathy | Typically lower extremities (feet or ankles) | Throughout United States (except Alaska) but most encountered in Eastern, Midwest, and Rocky Mountain states | Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Rickettsia disease, anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, Colorado tick fever, tickborne relapsing fever, tularemia |

| Widow spiders (Latrodectus) | Asymptomatic or pinprick Single, target lesion is classic, although not always present | Typically extremities, more often lower (accidentally encroaching on outdoor habitat) | North America | None |

Spiders

Spider bites are blamed for many necrotic wounds, but most spiders are harmless to humans. Many suspected bites are caused by other conditions such as Staphylococcus aureus infection.6 Spider bites typically present as a solitary papule, pustule, or wheal, and require only local wound care, analgesics, and tetanus vaccine prophylaxis. The two spiders of most medical significance in the United States are widow (Latrodectus) and recluse spiders (Loxosceles).

WIDOW SPIDERS

Widow spiders include more than 30 species with worldwide distribution. They are medium-sized spiders (up to 4 cm), characterized by shiny, dark-colored bodies with ventral red or yellow abdominal demarcations2 (Figure 1). The black widow (Latrodectus mactans) is the most predominant of the five widow spiders in the United States. Widows are rarely found inside the home and are typically encountered in shady enclosed spaces outdoors (e.g., sheds, yard debris, gardening equipment). Most bites do not result in systemic envenomation, referred to as latrodectism, characterized by excess acetylcholine release.7 When present, symptoms of latrodectism include muscle spasm and diaphoresis starting at the involved extremity and migrating proximally. Patients can present with nausea, tachycardia, hypertension, restlessness, and, rarely, severe abdominal rigidity or chest pain, which can be mistaken for peritonitis or myocardial infarction.2 Infants and children typically present as inconsolable with generalized erythema and excessive drooling. Symptoms typically come in waves and continue for 48 to 72 hours but are rarely life-threatening.7,8

Envenomation severity can be graded, which helps determine treatment8 (Table 22,7,8). Mild presentations can be treated with nonopioid oral pain medications, but opioids are sometimes indicated for poorly controlled pain. Benzodiazepines are widely recommended to treat painful muscle spasms; however, no trial data support their use.2,8 Calcium and magnesium have demonstrated no benefit and are not recommended.2,8 Widow spider bites are rarely life-threatening, and the use of antivenom is controversial. Limited data have demonstrated decreased pain duration with antivenom, balanced with a risk of allergic reaction in up to 5% of patients.7–9 Antivenom is not widely available in the United States and is generally only considered in patients with severe symptoms not responsive to supportive care.

| Grade | Clinical presentation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic to local pain at bite site Normal vital signs | Wound care, cold packs Oral analgesia (i.e., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen) Tetanus vaccine prophylaxis (if indicated) |

| 2 | Muscular pain in affected extremity extending proximally Diaphoresis of bite site or affected extremity Normal vital signs | Above treatments plus: Oral analgesia with or without parenteral opioids Oral or parenteral benzodiazepines for muscle spasm Antiemetic therapy |

| 3 | Generalized muscular pain in back, abdomen, and chest Diaphoresis remote from envenomation site Nausea or vomiting, headache Abnormal vital signs (hypertension, tachycardia) | Above treatments plus: Hospital admission Parenteral opioids Parenteral benzodiazepines Consider antivenom (if available) if refractory to supportive measures (especially in children and older people with comorbidities) |

RECLUSE SPIDERS

Recluse spiders are found predominantly in the Southwest and southern Midwest and are best known for the brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa), which are small (2 cm or less) brown spiders with a dark violin-shaped pattern on the anterior thorax (Figure 2). Many harmless spiders look similar and are frequently misidentified as brown recluses. Recluses are most commonly encountered indoors in dark, quiet areas such as furniture, clothes, and bedsheets. Recluse spiders are not aggressive by nature and only bite when antagonized, usually on the trunk if the patient inadvertently rolls onto or traps the spider in clothes. Bites typically resolve in one week or less, but an estimated 10% become necrotic after 24 to 48 hours, which may require weeks to months to heal and can result in scarring. Brown recluse bites are distinguished from other spider bites by the presence of a single, flat lesion without associated swelling.10

Recluse bites are generally managed conservatively, with most studied therapies (including dapsone, corticosteroids, antihistamines, early surgical excision, and hyperbaric oxygen) shown to be ineffective or cause harm.2,11 Good wound care with soap and water and tetanus vaccine prophylaxis (if indicated) are recommended in all cases. Antibiotics are not indicated unless evidence of a secondary infection is present. Antivenom is not available in the United States and is not recommended. A smaller number of patients may require surgical revision of the resulting scar after necrosis.

Loxosceles venom can cause hemolysis, which is more common in children and not predicted by the extent of cutaneous involvement. Life-threatening complications such as angioedema, renal failure, rhabdomyolysis, and death are rare.12 Patients with signs of systemic loxoscelism should be admitted and treated supportively.

Scorpions

Scorpions are arachnids that envenomate their prey through stings using their tails. Most scorpion stings are associated with self-limited pain, and fatalities are rare in the developed world. Stings typically occur on the extremities because the scorpions are cornered in hidden places or inside shoes and crevices.13 Stings are immediately painful and often associated with local paresthesias. The site is often difficult to identify, although local erythema, edema, and muscle fasciculations are common. Severe systemic envenomation occurs in less than 5% of stings and is more common in children. Centruroides (including bark and striped scorpions) are the only scorpions in the United States associated with severe envenomation.13 The severity of envenomation determines therapy, and multiple grading scales have been developed (Table 314–18). More severe envenomations are characterized by cranial nerve abnormalities, somatic neuromuscular dysfunction, and autonomic dysfunction. In the most severe cases, airway compromise, respiratory arrest, pulmonary edema, myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, and pancreatitis can result. Cardiomyopathy can occur in severe systemic envenomation secondary to catecholamine surge and is clinically similar to takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

| Grade* | Clinical effects | Evaluation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pain or paresthesias at sting site | Observation for at least 4 hours | Oral analgesia (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, opioids) Consider topical lidocaine or local anesthesia Local wound care Tetanus vaccine prophylaxis |

| 2 | Pain or paresthesias remote from sting site Agitation Nonsevere hypertension and tachycardia | Observation or hospitalization until symptoms improving and controlled on oral agents Consider consultation with regional poison control center (United States: 1-800-222-1222) | Oral or parenteral analgesia (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, opioids) Consider regional anesthesia Oral or parenteral benzodiazepines Consider adding prazosin (Minipress) |

| 3 | Neuromuscular dysfunction (i.e., muscle spasm, dysphonia, dysphagia) Cranial nerve dysfunction (i.e., roving eye movements) Severe hypertension, cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema Multi-organ failure | Intensive care unit admission Consider consultation with regional poison control center Renal function or electrolytes panel Liver enzymes and lipase Serum creatine kinase Complete blood count Coagulation studies Urinalysis Electrocardiogram and cardiac biomarkers | Antivenom Parenteral analgesia (e.g., intravenous fentanyl) Parenteral benzodiazepines (caution when administering antivenom) Endotracheal intubation and oral suctioning (if indicated) Noninvasive or mechanical ventilation (if indicated) Prazosin (or other vasodilators) for refractory hypertension Nitroglycerin for pulmonary edema Inotropic support with dobutamine (if indicated) |

Treatment is primarily supportive, ranging from local care in mild cases to sedation, ventilator support, and inotropic agents in the most severe systemic envenomations. Centruroides antivenom is available in the United States. Limited data suggest it can shorten recovery times, but a cost-effectiveness analysis supports its use only in severe envenomation cases.19,20

Hymenoptera

The Hymenoptera order consists of more than 100,000 species. The three clinically relevant groups capable of stinging are Apidae (bees), Vespidae (wasps, yellow jackets, hornets), and Formicidae (ants)21–23 (Table 422,24,25). Generally, stings occur by accidental contact or proximity to a disrupted nest.21 Four categories of Hymenoptera sting reactions are described, with distinct clinical findings and recommended treatment14 (Table 521–25).

| Arthropod | Geographic distribution | Nesting habits | Avoidance strategies | Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fire ants (Solenopsis) | Throughout United States; specifically, Western states and Southeast | Underground and in mounds | Routinely inspect playgrounds, yards, and exercise areas for mounds Use toxic baits to target queen ant Remove or cleanse outside garbage cans and clear eating areas of food that attracts ants | Swarm potential food and sting simultaneously via pheromones Typically sting 6 to 7 times in circular pattern (Figure 5) Defensive of mound, attack in swarm |

| Honeybee, bumblebee (Apidae) | Throughout the United States; abundant in the Southwest Within the United States, “killer bees” are found in Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and California | Social or commercial hives | Avoid dark and floral prints and fragrances Avoid walking through flowers Wear shoes and socks when outdoors Keep bananas away from hives (scent resembles their alarm pheromone) Avoid loud noises around “killer bee” hive | Human sweat and carbon dioxide from breath can agitate bees and provoke an attack |

| Hornet (Vespa) | Continental United States | Near people | Avoid floral prints and floral scents Remove nests when possible | Fewer stings can be lethal Tend to be more defensive and have large nest populations |

| Wasp (Polistes) | Throughout United States | Under houses, eaves, barns, mail-boxes, playgrounds, shrubbery, cavities of trees | Avoid floral prints and fragrances Stay away from food waste and open garbage, keep garbage cans and areas clean Remove nests when possible | Tend to be attracted to food waste |

| Yellow jacket (Vespula and Dolichovespula) | Temperate regions of United States | Underground, shrubbery, trees | Avoid open food sources, picnic areas, and garbage Remove nests when possible | Tend to be attracted to food waste, specifically sugary foods Aggressive Any disturbance of the nest will likely provoke an attack Occasionally leave their stingers in the skin |

| Reaction | Description and clinical manifestations | Management | Time course |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local (most common) | Painful; small area of edema at sting site surrounded by erythematous flare up | Supportive care: ice or cool compresses, analgesics, topical lidocaine, antihistamines, corticosteroid lotions | Minutes to hours; resolves after approximately 24 hours |

| Large local or regional (19% of reactions; carries 5% to 10% risk of future systemic reaction) | Area of erythema > 10 cm (3.94 in) with erythema and induration involving contiguous parts of the body as the sting site | Supportive care and glucocorticoids Adults: prednisone, 40 to 60 mg per day for 3 to 5 days Children < 12 years: prednisone, 1 to 2 mg per kg per day for 3 to 5 days | Several days to 1 week after sting |

| Systemic (anaphylaxis; 1% to 3% of reactions) | Immunoglobulin E mediated; generalized angioedema or facial swelling, urticaria, respiratory distress or wheezing, abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting, flushing, shock | Hospital or emergency department monitoring Adults: intramuscular epinephrine, 0.3 to 0.5 mg to anterolateral thigh (repeat every 5 to 15 minutes as indicated) Children: intramuscular epinephrine, 0.01 mg per kg (maximum: 0.5 mg) to anterolateral thigh (repeat every 5 to 15 minutes as indicated) Glucocorticoids (prednisone, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone) Antihistamines | Rapid onset, seconds to minutes |

| Delayed hypersensitivity | Serum sickness, skin rashes, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis, neuropathy, cerebral edema, disseminated intra-vascular coagulation, arthritis | Supportive care Consider glucocorticoids depending on severity | 3 days to 2 weeks after envenomation |

| Massive envenomation | Rhabdomyolysis, acute renal or hepatic failure, hemolysis, myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, convulsions | Supportive care | Dose dependent |

Hymenoptera envenomation causes an average of 62 deaths each year; however, most stings are self-limited and treated supportively.26 Most deaths are caused by anaphylaxis and rarely massive envenomation. The risk of severe systemic reaction is highest in older adults, small children, those receiving multiple stings, and when there is a short time to symptom onset.23,24

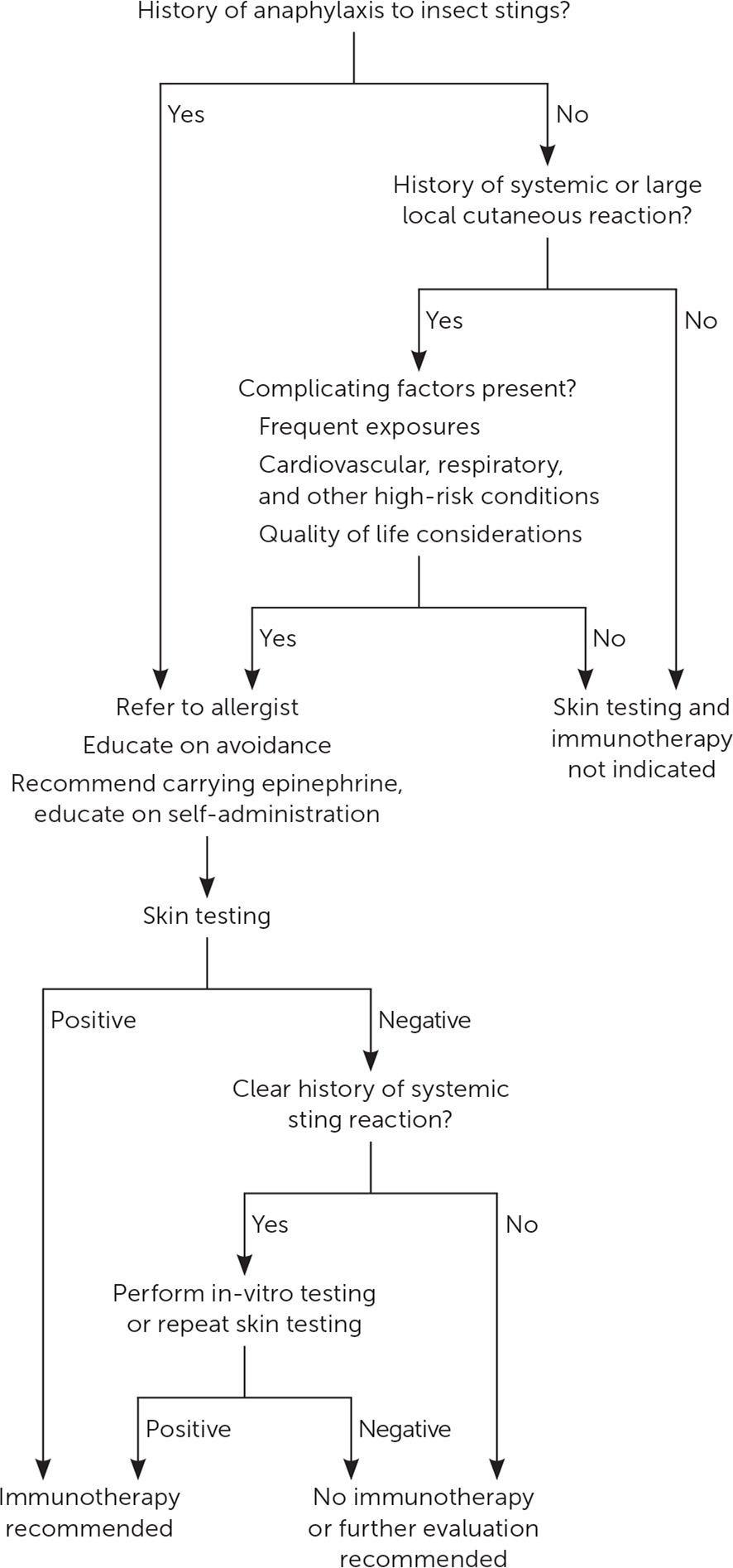

Patients with a history of systemic allergic reaction to an insect sting have an approximately 50% risk of recurrent systemic reaction and should be evaluated with skin testing and, if positive, treated with venom immunotherapy, which can decrease the risk to less than 3%.27,28 Figure 3 outlines the recommended approach for patients with a history of allergic reactions to insect stings.27

APIDAE (HONEYBEES, BUMBLEBEES)

The Apis (honeybee) and Bombus (bumblebee) genera are the most commonly encountered bees. They are typically docile and only sting when threatened or provoked. When a honeybee stings, it leaves the stinger in the skin and dies shortly after. Bumblebee stingers do not detach, permitting multiple stings.

| Using a dull blade or credit card, press the flat edge against the skin. |

| Turn the blade or card at an angle that is almost parallel to the skin. |

| Apply gentle pressure and sweep the edge over the top of the sting site to dislodge the stinger without squeezing. |

| Avoid using tweezers or squeezing, which can result in the injection of additional venom into the sting site. |

VESPIDAE (WASPS, YELLOW JACKETS, HORNETS)

Relative to the Apidae, wasps, yellow jackets, and hornets tend to be more aggressive and are universally capable of multiple stings.22,24 Yellow jacket stings tend to peak in the summer and autumn when populations are highest, and they characteristically swarm, making multiple stings common24 (Figure 4).

The spectrum of possible reactions to vespid stings is similar to the Apidae family, except for hornets. Lower doses of venom may be required to reach lethal levels for hornet stings, and hornets tend to deliver more venom per sting. Multi-organ failure and death are more commonly associated with hornets relative to other Hymenoptera.24

FORMICIDAE (STINGING ANTS)

The Solenopsis species (fire ants) is the most commonly encountered stinging ant in North America. Most fire ants are 3 mm to 8 mm long with reddish-brown or black bodies and are known to swarm and sting the lower extremity in clusters (Figure 5). Immediate- and delayed-hypersensitivity reactions occur with stings.

Diptera

The biting Diptera include mosquitoes, blackflies, phlebotomine sandflies, tsetse flies, biting midges, horseflies, and stable flies. Diptera most significantly affect humans as vectors for infectious diseases. The mosquito is the most clinically relevant (Figure 6), but each biting Diptera can serve as a vector.

Some may experience an allergic reaction to the components of mosquito saliva, called Skeeter syndrome. Chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection and other lymphoproliferative syndromes have been associated with a hypersensitivity reaction to mosquito bites that include high fever, bullae, and skin necrosis.29

Bedbugs

Bedbugs (Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus) are increasingly prevalent parasites that readily feed on humans and mammals. Bedbugs have ovoid-shaped 5-mm long bodies with yellow or red-brown coloration. Bedbugs typically feed at night and are commonly found on mattresses, box springs, curtains, and bedding to avoid light. Bites generally cause self-limited cutaneous reactions.30,31 A previous American Family Physician article describes the identification and management of bedbugs (https://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1001/p653.html).

Mites and Chiggers

Mites (including chiggers) are insects in their larval form and less than 1 mm long that commonly bite humans. Sarcoptes scabiei can cause a persistent infestation in humans known as scabies (https://www.aafp.org/afp/2019/0515/p635.html). Although infected chiggers can transmit scrub typhus (a vector-borne zoonosis) in South Asia, this is not endemic to the United States.32

Fleas

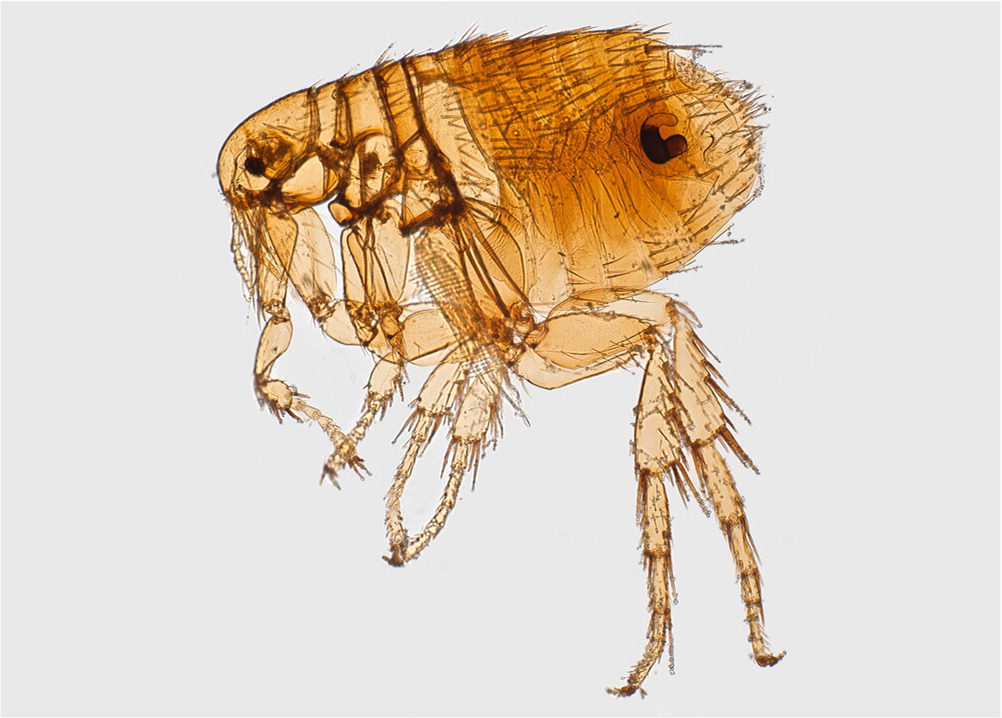

Fleas are small (less than 5 mm), wingless, jumping insects that feed on human and animal blood (Figure 7). In the United States, the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis) and the squirrel flea (Oropsylla montana) are the most common and are vectors for the plague, cat-scratch fever, and flea-borne (murine) typhus.33

Ticks

Many ticks in the United States (e.g., Ixodes, Amblyomma, Dermacentor, Rhipicephalus) are vectors for significant human diseases.3 Transmission of pathogens by a tick bite is time-dependent, making prompt removal of the tick important.34 The pathology and management of tickborne diseases are described in a previous American Family Physician article (https://www.aafp.org/afp/2020/0501/p530.html).

Prevention

Topical skin repellents work by stimulating avoidance behaviors or blocking receptors rather than direct toxicity.35–37 N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET; 20% to 50%) is the most highly studied repellent with the broadest spectrum of protection (Diptera, chiggers, fleas, ticks). DEET is safe for use in people older than two months, during pregnancy (after the first trimester), and when lactating. Concentrations of 20% to 35% offer the best balance of effectiveness and safety with approximately five hours of protection.35–38 Para-menthane-3,8-diol is a plant-based repellent derived from lemon eucalyptus with inconsistent and limited data suggesting similar effectiveness to DEET.35,36 Icaridin is odorless and nonoily and has similar effectiveness to DEET with less durability.35,37 Insect Repellant 3535 is a new product that offers protection against mosquito bites; however, safety data are lacking for use in children or people who are pregnant or lactating.37

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using Clinical Queries and medical subject headings with key terms spider bite; spider envenomation; scorpion sting; scorpion envenomation; hymenoptera stings; hymenoptera envenomation; hymenoptera venom allergy; hymenoptera venom immunotherapy; mosquito bites; biting diptera; flea bites; mites; chiggers; fire ants bites; bedbugs; insect prevention; arthropod prevention. The search included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, significant case series, and reviews. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, Trip database, the Cochrane database, UpToDate, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Search dates: April 11 to 28, 2021; May 26, 2021; June 19, 2021; and Mar 9, 2022.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.