More efficient note writing through EHR simplification can reduce physicians' documentation burden and make practice more fulfilling.

Fam Pract Manag. 2022;29(4):19-24

INSIDE: Six tips for physicians

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

Documentation burden is a significant issue for family physicians due to competing demands. These demands include organizational documentation guidelines that may not reflect national guidelines, ever-changing clinical workflows that add more work for clinicians, and electronic health record (EHR) systems that often require multiple entries and clicks to meet billing requirements. In 2021, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) revised its documentation guidelines for evaluation and management (E/M) services, which simplified the billing requirements for these visits. However, many physicians still struggle to balance their time between patient care and documentation.1,2 Simplifying EHR features and documentation requirements at an organizational level can reduce the burden on individual physicians and spur more efficient note writing, which leaves more time for direct patient care and makes practice more fulfilling.

This article will describe the approach our organization took to simplify its EHR and improve note-writing efficiency and will offer tips for individual clinicians to improve their own documentation.

KEY POINTS

Documentation burden is a multifactorial problem resulting from complicated billing guidelines, the lack of truly user-friendly documentation tools within EHRs, and clinician culture and behavior.

To improve efficiency in the way we write notes requires organizations and clinicians to embrace a culture of continuous process improvement.

The authors' project to reduce documentation burden involved leadership buy-in, education on the new E/M guidelines, a multidisciplinary team, standardized EHR tools, and iteration.

THE IMPROVEMENT PROCESS

Burdensome documentation may feel like a problem that is too big to solve, but it can be approached like any other practice problem using continuous process improvement.

Start at the top

When working on any change in clinical practice, including reducing documentation burden, having buy-in from leadership is critical. Leaders must be invested in the project's success, able to allocate the necessary resources, eager to highlight the team's work, and willing to allow the team flexibility to develop, pilot, and implement changes. Leadership involvement during project formation helps ensure that appropriate, attainable, and realistic goals are set from the start.

In our case, institutional leadership recognized widespread problems with documentation efficiency, including the fact that our notes had not changed significantly following the release of the 2021 E/M guidelines. Our department chair was committed to easing documentation burden and approved a team of faculty to work with the Information System Development (ISD) team to identify improvements. The chief medical information officer developed the concept of “Notes 2.0,” an institutional approach across departments to streamline note writing, and the practice medical director sponsored the project.

Leadership buy-in will look different in other settings. For example, in a smaller practice, physicians may have fewer levels of leadership to navigate, which is a plus. On the other hand, smaller practices may have fewer resources available to them. Each setting has its pros and cons, which must be navigated to get the project off the ground.

Get clear on the guidelines

The first priority for the family medicine Notes 2.0 team was making sure clinicians understood the new E/M guidelines. We worked closely with our billing and compliance staff, who helped break down many bad habits and lore about what has to be in a note for legal, billing, compliance, or regulatory reasons. We used clinician focus groups, questionnaires, and our EHR to gather data about the areas of documentation and in-basket work that were most problematic. For example, common pain points included having to reenter information in visit notes that already exists elsewhere in the EHR, and having to enter patient responses from paper-based questionnaires that don't match note templates. We clarified what items are no longer needed based on the new guidelines (e.g., physician documentation of the history of present illness [HPI], review of systems, and exam bullet points), what items are required for billing and compliance (e.g., medical decision making or time), and how best to include these required items in notes without affecting clinical workflow. We revisited the primary purpose of a clinical note — clear communication about what happened during the visit — and identified common sources of “note bloat,” such as copying information from previous notes or other areas of the chart and unnecessarily including it in the current visit note. We then developed directed education for our clinicians.

If a practice does not have billing and compliance staff who can help with this step, it could bring in a coding consultant to conduct an educational session, or have one of the practice's physicians who is well-versed in the E/M changes lead the education, using readily available resources. (See “Related resources.”)

Take a team approach

Team-based care, in which all members work at the top of their license, not only improves patient care but also enhances staff and clinician joy and dignity in their work. Applying a team-based approach to documentation is one strategy to share the work. Although the name at the bottom of the patient's note is the clinician's, the document is a culmination of efforts by many team members involved in the patient's care. Team-based documentation requires effective communication and collaboration across many previously siloed areas, from check-in and rooming staff to nursing staff to clinicians. To ensure that our EHR supported the roles and efficient documentation of all our members, and to ensure compliance with billing and other guidelines, we involved key stakeholders and experts, including members of our legal, billing, compliance, and ISD teams. This team worked collaboratively to drive effective changes in technology, process, and culture around note documentation.

Create standardized tools for documentation

Once our team had a clear understanding of the documentation requirements, we enlisted IT staff familiar with our EHR to help us create tools to improve clinical workflows. Many clinicians do not realize that their EHR can be adapted to better meet their needs. This does require IT resources, which we were fortunate to have. Alternatively, practices could work with their EHR vendor or perhaps a physician superuser or other person responsible for EHR implementation or optimization.

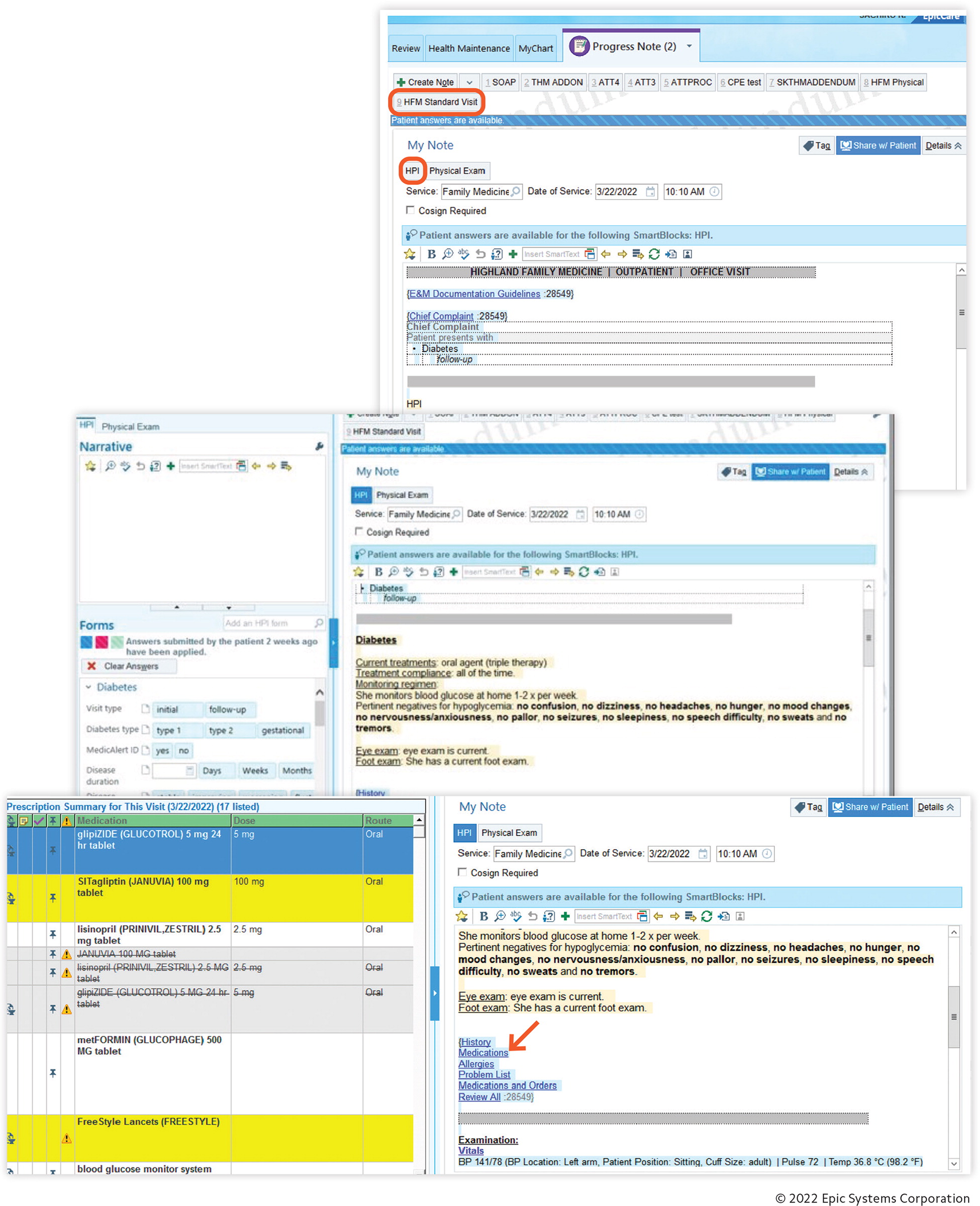

Two major EHR products we created were a “Standard Visit Note” template and a “Complete Physical Exam Note” template. To add to the Standard Visit Note template, we created standard patient questionnaires to cover the most frequent chief complaints: diabetes, hypertension, and pain/illness. Diabetes and hypertension questionnaires include patient-generated information such as medication adherence, home measurements, symptoms/complications, and pertinent care gaps (e.g., foot exams or eye care). The pain and illness questionnaire includes standard questions about location, duration, progression, and associated symptoms. Patients can complete the relevant questionnaire online prior to their visit, and their answers automatically populate the HPI section of the note, reducing the team's documentation during the visit. For patients unable to complete the questionnaires ahead of time, rooming staff may pull up the questionnaires in the exam room so patients can answer them while waiting for their clinician. The Complete Physical Exam Note template pulls health maintenance needs, depression screening, and social history into the note from data found elsewhere in the EHR. For these visits, rooming staff have patients complete a physical exam intake form (currently paper-based), which has the same questions as the Complete Physical Exam Note template. Clinicians then review and enter the patient's answers in the note template with a few clicks.

The note template contains hyperlinks to past medical history, past surgical history, medications, and allergies. With one click, without leaving the chart note, the clinician can view these elements of the patient record and edit them as needed. Reviewing these elements is documented behind the scenes, so it counts toward medical decision making. These elements are not included in the current visit note, thus reducing note bloat. We removed the review of systems (ROS) from our note templates because it is no longer required for E/M visits, was never required for preventive visits, and contributes to note bloat.

We also introduced the following tools:

A standardized EHR dashboard customized for family medicine that displays pertinent patient data for chart review without the clinician needing to open the chart. A key addition to this dashboard, previously unavailable, was the most recent urine drug screen.

A standardized “pick list” of chief complaints, which staff can select during the rooming process, ensuring inclusion of the appropriate patient questionnaire. The institution plans to expand these questionnaires as other departments take part in this project.

Comprehensive preference lists of frequently ordered labs, imaging, and treatments that allow clinicians to select these items in fewer clicks and less time.

Each of these tools reduced the time and clicks required for clinicians during encounters and associated documentation.

Address challenges through iteration

As expected for a practice-wide endeavor, the project had its challenges and lessons learned. For example, following the initial release of the tools, early feedback revealed unanticipated technical glitches, a preference for more succinct questionnaires, clunky templated HPIs, and lack of motivation from staff to add yet another task to the rooming process. Additionally, the inability to have multiple HPI questionnaires completed for a given visit (e.g., hypertension and diabetes) and lack of an online annual physical exam questionnaire limited the project's utility in a busy primary care practice where complex patients have multiple issues and preventive medicine topics to discuss. As a result, some clinicians chose to continue using their old templates, which often included outdated or unnecessary information.

Eliciting staff and clinician feedback was essential to adapting and improving the tools. Delays inherent in seeking feedback and implementing changes made the process less agile. But we have since established an internal physician team to continue collecting feedback and iterating on the documentation tools to achieve critical ongoing improvements in collaboration with the IT build team.

TIPS FOR INDIVIDUAL PHYSICIANS

Be open-minded and flexible

Using new tools takes practice and will likely require some patience as they are refined over time, but the improved efficiency will be worth it. Instead of trying to perfectly implement new documentation habits across every visit immediately, consider trying something new for just a few visits during the day as you transition.

Write notes you can quickly read and use for clinical care later

Bloated notes are difficult to read and make it is easy to miss critical information. Write the minimum while still conveying your thought process and plan so your future self and team members can quickly understand them.

Don't do all the HPI documentation yourself

Use EHR features that let others (patients or staff) document key elements of the HPI. When using intake forms (e.g., for physical exams) make sure they match note templates, and leverage features such as “click all normal” to make documentation of standard visits much faster. Lastly, remember to document critical information such as duration and location of symptoms.

Be mindful of what extras you add

Learn and follow the new E/M guidelines. Resist the urge to keep unnecessary components (such as ROS), include unnecessary statements (e.g., “past medical history reviewed”), or pull in extra data you can see elsewhere in the EHR. If certain data are important, mention them in your history, assessment, or plan. If you want to add extra reminders, such as check boxes or diagnostic criteria for a condition you are unfamiliar with, remember they are “training wheels” that can be removed as you become more familiar. Keep these reminders to a minimum to reduce the noise in your notes. Additionally, remember that family physicians should ask only the pertinent questions for each condition we address, especially when reviewing multiple conditions in one visit.

Document during or soon after the visit

It takes more time and effort to write notes after you get home or on another day. The best time to document notes is before seeing the next patient, while your memory is freshest. Ideally, you should document the HPI and physical exam during the encounter, using either system-based phrases or quick features in the EHR. If you have a template for the physical exam but you constantly have to delete or change it, consider adding a minimal phrase such as “General appearance: not in acute distress,” and just add what you actually did, or change the template to something requiring minimal change. If you have templates for assessment and plan that document stability (controlled vs. uncontrolled) based on available data in the EHR (such as A1C, blood pressure, or depression screening score), you can add these sections while you are wrapping up your visit. If you want to summarize your thought process in your assessment and plan after the patient leaves, try to type or dictate it right after each visit. Dictation software can be helpful for this. Give yourself a break if you occasionally have a rough day and can't do it. When you return to the task, start with one or two patients who have simpler or more stable conditions.

Continue ongoing updates

When it comes to EHRs, there are always going to be things to improve or bugs to fix, just like our smartphones or computer software. You may also find unexpected glitches in the workflow. If you find a bug or have an idea for improvement that can help others, give feedback to your technical team to improve the products and to your leadership to improve the workflow.

Related Resources

E/M coding changes:

The 2021 Office Visit Coding Changes: Putting the Pieces Together. FPM November/December 2020.

2021 Office Visit E/M Coding and Documentation Reference Cards. AAFP.

2021 outpatient office E/M changes FAQ. FPM Quick Tips blog. Nov. 6, 2020.

Countdown to the E/M Coding Changes. FPM. September/October 2020.

MDM data FAQs: Don't double-count the order and review of a single test. FPM Getting Paid blog. Jan. 28, 2021.

Outpatient E/M Coding Simplified. FPM. January/February 2022.

Tips for using total time to code E/M office visits in 2021. FPM Getting Paid blog. Nov. 23, 2020.

Documentation efficiency:

Seven Habits for Reducing Work After Clinic. FPM. May/Jun 2019.

Ten EHR Strategies for Efficient Documentation. FPM. July/August 2020.

MOVING FORWARD

Documentation burden is a multifactorial problem resulting from complicated billing guidelines, insurance rules, government incentive programs to promote EHR use, the lack of truly user-friendly documentation tools within EHRs, and clinician culture and behavior. To improve efficiency in the way we write notes requires organizations and clinicians to embrace a culture of continuous improvement, which will ultimately result in better patient care and more joyful practice. As technology advances, more opportunities for improvement and automation will arise, such as patients or even artificial intelligence providing more information directly. These changes will enable more patient-centered and personalized care, allowing family physicians to do what we do best — patient care — not clicking check boxes.